StudentCreatedRubricArticl

advertisement

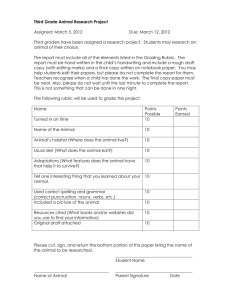

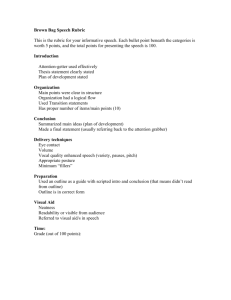

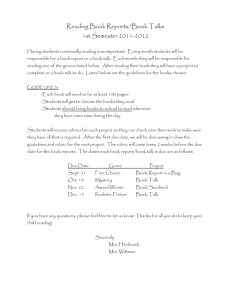

APERTURES AND OPPORTUNITIES: HANGING PEER REVIEW ON OUR RUBRIC Hannah Ashley, Nicole Fugelo, Gaetan Pappalardo, Andrew Stout APERTURES From: Pappalardo, Gaetan Sent: Friday, December 10, 2010 9:03 AM To: Ashley, Hannah Subject: Rubric paper Hannah, I just did the rubric thing with my class. Absolutely loved creating the rubric. I took a picture of class rubric we made in poster form. I attached it. I had to make some adjustments. For example: My students rarely get an assignment, so the rubric we created is a general rubric that will help all first drafts. I like the idea of this rubric as a fluid document that we can adjust as the students improve their writing. I plan on making smaller individual rubrics, laminated, so they can use a dry erase marker on them. I like this idea as a non-grading rubric for my grade level. It's more of a guide to first draft writing: an awareness. gaetan *** My students’ comments—they gave me a lot more insight into what they thought about writing and how their writing is assessed… -Nicole Jesse: “I want my creative language and word choice to be recognized” Jen: “Why are we doing this? Shouldn’t you just tell us what you want, like content, organization and all?” Carol: “I already struggle with writing so I want some recognition for the little things like MLA format, indents, line spacing.” *** As a composition faculty member at a state system university with a four-four teaching load, I teach a lot of writing intensive courses. Even the courses that I teach which are neither first year composition nor 1 formally labeled writing intensive typically have a lot of writing in them. Consequently, I have a whole variety of practices that I use to “teach writing.” I have used contract grading. Sometimes I send my students MP3’s of my feedback, orally recorded. Often, I conference one-on-one with students. However, a highly consistent practice that I have used is the co-creation of grading rubrics with my class as the center of the peer review process. I have found that this practice is an incredibly productive way to teach writing and writers—and it happens to reduce workload as well, and can address other issues of writing process, writing studies, and progressive pedagogy. This essay theorizes the practice I have developed over a number of years of teaching, details the process, and offers brief, informal reflections of two inservice teachers in K-12 schools who piloted implementing the practice in their two very different classrooms. We argue that when peer review is grounded in collaborative construction of grading rubrics—while it is not a panacea for the challenges of teaching writing—it serves to address issues of power, student engagement and learning, and the material conditions of teaching. *** Since 1988, at perhaps the tipping point of process and post-process pedagogies’ shifting ascendance, when Anne DiPardo and Sarah Warshauer Freedman published their essay, “Peer Response Groups in the Writing Classroom: Theoretic Foundations and New Directions,” a great deal more has been written about peer review. The discipline continues to work toward an understanding of what peer review actually does, if anything (as some wonder), and if so, what aspects of the Collaborative Peer Review and Response (CPRR) process are effective. Within this larger discussion, the term “collaboration” carries quite an encumbered consignment of work. What do we mean when we say students collaborate through CPRR? Muriel Harris notes the rather “tangled” use of the term in her essay, “Collaboration Is Not Collaboration Is Not Collaboration: Writing Center Tutorials vs. Peer Response Groups,” specifying classroom “collaboration” as 2 collaboratively learning about writing [which] involves interaction between writer and reader to help the writer improve her own abilities and produce her own text—though, of course, her final product is influenced by the collaboration with others. (369-370) But what that learning and help might mean in specific application varies from scholar to scholar and classroom to classroom. For example, Corbett and Guerra, in “Collaboration and Play in the Writing Classroom,” argue for the importance of classroom collaboration as playful and experimental, pushing at the boundaries of authority, but also noting that, in so doing, students can exchange various forms of valuable information, ranging from “rhetorical strategies” to knowledge about “academic discourse.” Dipardo and Freedman cite Freedman’s study in their essay that collaboration works best when students are actually collaborating on a product or are working out a problem together—not critiquing each other’s individual texts. Both Corbett and Guerra and Dipardo and Freedman observe that while some peer review scholarship takes “developing a writing community” and consensus as its rationale, other voices in the discipline (e.g., Trimbur) suggest that discensus and conflict may be more productive for learning. Though CPRR as a beneficial practice is often taken for granted—“I also sleep better at night knowing that my comments aren’t the only comments they [students] are depending on” (Belcher 106)--some research indicates that receiving peer commentary may not be helpful at all. Lundstrom and Baker, in their research with ELL students, “To Give is Better than to Receive: The Benefits of Peer Review to the Reviewer’s own Writing,” note that their “givers” improved more than their “receivers” of feedback. To explain this differential, they cite Rollinson’s claim that peer revision may “lead to the creation of better self-reviewers, or students who are able to look at their own papers and accurately assess areas in which they need to improve and revise them” (31). Freedman’s claim that working on individual student texts in CPRR is not particularly productive could be explained similarly. Even further, Covill’s study, “Comparing Peer Review and Self-Review as Ways to Improve College Students Writing,” indicates that students’ writing improved more with no peer review than with, and that students’ subjective experience of writing instruction was more positive without peer review than that of those conducting peer review (220). Issues of power and authority, as well as the practical nature of the material conditions of teacher labor, are also under contention. Harris notes that some faculty may feel marginalized by using CPRR— essentially being viewed as those who stand aside and look out the window while students do the work (381). “The real issue is how to devise ways in which teachers and students might productively share power, but on this point the literature has been largely silent” (DiPardo and Freedman, 127). 3 The use of rubrics, in some ways, seems to oppose the underlying orientation of the CPRR approach. Some students and faculty cringe at the mere mention of a rubric, understandably in this era of standardized testing (an orientation, however, which is clearly not new but echoing back to 1912, when Ernest C. Noyes argued that “What is wanted is a clear-cut, concrete standard of measurement which will mean the same thing to all people in all places and is not depended upon the opinion of any individual” (as cited in Turley and Gallagher 88)). However, a rubric is not a rubric is not a rubric. Rubrics can and often are used rigidly to assign grades and prescribe requirements. But they can also be descriptive evaluation guides or tools of critique (Turley and Gallagher). Thus, re-enter collaboration, both among students, and among students and faculty. Turley and Gallagher provide the example of using “words that students value more highly than we do,” such as “flow,” in rubrics (90). Faculty can opt to negotiate with their students, to figure things out alongside them, not just in the service of a critical pedagogy, but because authentic constructivist learning takes place when such negotiations of conflicting values and knowledge occur. Turley and Gallagher point out that in cocreating these rubrics, students will not only be more equipped to navigate the assignment at hand, but that co-created rubrics exist as “a launching point for conversation: a place to start, and never a place to end” (92). Sounds like the best conceptions of CPRR—a foundation from which engaging, playful and thought-provoking discussions are launched. The literature and my own experience suggests that when instructors provide students the opportunity to co-create rubrics in the context of CPRR—working together to negotiate with each other guidelines for assignments and ultimately the grading instruments for the assignments—students are provided one fruitful opportunity to become the kind of post-process writers many of us are striving for: writers who understand occasion and audience and genre and are able to develop transferable sets of skills in terms of figuring out, explicating, negotiating and pushing back at literacy/discursive expectations. APPLICATION: HOW IT WORKS This practice developed out of the theoretical knowledge base, as summarized above, plus some of my own orientations to and experiences with teaching, which are further addressed in the final section. The overview of the process is that students negotiate with each other and the instructor to co-create grading rubrics as a direct outcome of the peer review process, after first drafts have been completed. For ease, the steps are numbered below. They are: draft, read, chat, represent, nominate, specify, negotiate, revise. 4 1. DRAFT. Students receive the assignment, whatever the writing task may be. In what I view as a fairly typical fashion, they may get support in class from me and their peers in a variety of ways in order to draft (simple discussion of the assignment, brainstorming, pre-writing together, etc.). Peer review drafts are expected to be “finished.” I typically say, “Don’t think of these as half-drafts, or ‘rough’ drafts, but as strong as you can make them.” This is important, as students can’t construct strong, complete rubrics from half-finished papers nor pieces on which they have not put in their best efforts. 2. READ. In class, I begin by having students read each other’s drafts in pairs. Of course, I don’t have a peer review guidelines sheet, but neither are students’ readings completely unstructured. Instead, I tell them that they are looking for the strengths of the piece in front of them: what works, what is effective. I stay away from language such as “what you like,” though students sometimes start there anyway, probably reflecting intuitive ideas about the effective features of a piece. I also tell them to feel free to mark up the piece, but that they are not focusing on “fixing” the grammar. (In fact, I don’t penalize for sentence-level error at all, ever—only for lack of proofreading; that is, what I call “typos.” When we build the rubrics, students often feel that they have to include these concerns in the rubric, but when I assure them that they do not, even well-drilled students are relieved and pleased.) 3. CHAT. After students read in pairs, I typically give them just a very few minutes (perhaps two to three minutes each way) to “chat” in an unguided way, to provide feedback to their partners in a general way. Students often use this time to sneak in comments about later/lower order concerns such as grammatical error and typos, or other very basic aspects of meeting assignment guidelines (length, headings, etc.). I have found that students need this time to “blow off the steam” of the typical expectations of teacher-driven, school-based writing. 4. REPRESENT. Then students get into groups of four—two pairs. I instruct them to represent the strengths of their partner’s piece to the group. This is one area of challenge, as they are tempted to rotate 5 all the papers around at this point. I actively discourage that, sometimes actually having to stand near a group and wait until they hand each others’ papers back to the original readers. (They will do this closer reading of one paper anyway in the next steps.) This step is where the “meta” about writing begins, and it is important. I want them to attempt (though it is hard) to talk about “what makes this writing good.” Although students don’t like the part about having to think out and articulate what makes their partner’s piece effective, they very much appreciate that they are not being publically “called out,” even in the small group. Since only the strengths are supposed to be represented, their egos (like all of our egos as writers and people) are less threatened. This safety seems to allow them to engage more deeply in the discussion of writing. Of course, by omission, and sometimes by way of conversation, weaknesses, gaps and problems emerge as well, but students appear to have the affective experience of having their best efforts highlighted. (Nicole strongly endorsed this insight in her high school classroom as well.) 5. NOMINATE. Of the four papers, they need to nominate one “best” paper. When I first started using this practice, I told them that one of the four papers was going to get turned in for a draft grade for all four individuals; however, this ended up upsetting students far more than necessary and it did not seem to add to the quality of the paper they chose nor their revised papers later on. Students resisted and almost seemed to choose mediocre papers as a way of saying, “this isn’t fair.” It also added to my workload, as I had to grade those papers. Currently, I always acknowledge that all the papers will have strengths and weaknesses, that probably there is no one “best” paper, but for the purposes of discussion and rubric creation, they have to nominate one anyway. 6. SPECIFY. I then go around to the groups to solicit specific information about the nominated paper. At this point, the nominated paper gets read or scanned by the other two students in the group. Typically, it works well in terms of classroom management, as groups take varying amounts of time in their nomination process. A typical conversation looks something like, 6 Hannah: “Ok, who’s chosen a paper? … Ok, Jane’s paper? How come?” Student: “Well, it flows.” Hannah: “What do you mean, it flows?” Student: “You know, it just all goes together.” Hannah: “Well, I can’t put ‘flow’ on a rubric [contra Turley and Gallagher!]—I wouldn’t know how to grade it. How do I grade flow? [Students laugh.] Can you try to figure out a more specific way of describing what you mean by flow? Can you point to ‘flow’ in her paper?” This is where teachers of writing as experts with meta-knowledge of composing and texts really becomes operationalized. Students need scaffolding to move from instinctive, knee-jerk reflexive, or habitual ideas about what good writing is to thought-out descriptions of those textual features. What, really, makes this particular piece an outstanding one? Once a feature is identified, how can we spell out, on the rubric, that characteristic? Sometimes I don’t know why something is good either—not right away. We have to figure it out together. As a teacher, I have to be willing to not-know with my students, and have the confidence in my own abilities to facilitate zone-of-proximal-development learning. The open, experimental nature of this process is also challenging for teachers. Nicole’s reflections included: This is important because I too struggled with this in my application of the process and felt I ended up giving more information to the students than I needed to—I should/could have let them get there on their own. Before large group discussion and negotiation in step 7, I usually solicit one feature from each group to put up onto the rubric, to start filling in the empty table on the board (or projected up using my computer) that looks like this: 7 A (Exceeds target) B (Target) C (Acceptable) Content Style When students offer me something that seems is usable (beyond a generality to something somewhat operationalized), at least to start, I will often say, “Ok, that sounds like a content issue (or a style issue— whichever)…now, is that A, B or C criteria?” That often takes some debate, even among the four students proposing that idea. If they are not sure, I suggest where I think it should go to start but let them hash it out. If this process sounds like chaos, it’s not. Students typically hone in on at least some aspects of the assignment, just instinctively. That is, they reference the assignment, or the genre, or the purpose of the piece as reasons why a certain aspect of writing is “good” in this instance. Students are often smarter about genre and occasion than pre-formed rubrics can be—not just in college, but even in high school, even in third grade. 7. NEGOTIATE. Once we get some initial working criteria, we review the rubric together. This penultimate stage is where a lot of really exciting learning and provocative debate about writing can happen. For example, if we have an initial gambit for an A criterion under Style, “Contains a clever extended metaphor,” then I ask, “Ok, can everyone agree to this?” Initially, most students nod their heads. Then I say, “Ok, so for your paper to earn an A, it has to contain a clever extended metaphor,” and all of a sudden there is controlled pandemonium. “My paper doesn’t have a metaphor! But it’s good!” Then we begin to think out what the higher-order feature is, the more general feature which “metaphor” is one way to operationalize. For example, metaphor might turn into, “Writing is original, not clichéd (e.g., metaphor, story telling, etc.) in service of ideas.” 8 There is often clarifying debate about A versus B versus C criteria, both in terms of what is just “doing the assignment” (B/Target), what is “a good try” (C/Acceptable), and what is “above and beyond” (A/Exceed Target). (Note: I also add a D/F column, for “unacceptable” practices, like plagiarism, or excessively far outside the page limits, etc. I always include a general, “does not address one or more aspects of the assignment.”) As a side benefit but one clearly important to our material working conditions if copyroom conversation are any indicator, because of this debate, I rarely have students complain about the grades they receive on papers. We continue to negotiate, discuss, and fill in the rubric. Occasionally something key from the assignment gets left out, but often most aspects of the assignment are addressed in the rubric students have taken leadership in creating. 8. REVISE. Students take home their pieces and revise. In my college classes, with the availability of Blackboard or similar systems, I can often finalize the rubric right then in class and email to them immediately, or certainly by the end of the day. *** A lot of discussion occurred about what they “hate” about other rubrics and what they wish would actually count toward their grade. This led to some changes I had in the assignment because of the insights the students gave me about the process of the paper and not just the assignment itself. I ended up giving them time in the library for a day to get more research done and then more credit for their completed research done prior to when the first set of citations were due. I also had to continually re-explain to them that this was an acceptable way of writing, that it was ok for their rubric to be created by the class. What I told the students was that it is helpful insight as to what should be completed in the process of writing and what is worthy to be included in the final product. They seemed content with that. Another part of the discussion was if this would actually help them in college, as with seniors it is a constant discussion. I enjoyed telling them that I got to do it in my masters-level course, but that it was possible this was a one time deal…though I hope for it not to be. And the lower level students better understood where I was coming from based on their participation in the collaboration of the rubric which had roots in the assignment they were to “get.” 9 Finally, the most interesting occurrence was that the students asked for no homework that day so they could better work on their next drafts (we called those the “rough” drafts) because they had a stronger understanding of what was expected based on the final draft of the co-created rubric. I of course did this. The rough drafts were ten times better than any other rough draft I had seen. *** I think third graders really enjoy the awareness part of it, so they have a rough guide at what makes "good writing" with the freedom to choose genre and style. Since I do not give informal or formal prompts during the first half of the year, I might have an epic fantasy tale and a poem. Or a narrative about a bully and an informational piece about weather. The second half of the year, we narrow a bit with some prompts to prepare for the state test…Also, it also promotes self-awareness (responsive classroom) and UBD (Understanding by Design) which is all of the rage right now. Picture caption: Rock on/Peace/Get to work 10 OPPORTUNITIES: POWER, STUDENT ENGAGEMENT AND LEARNING, AND MATERIAL CONDITIONS OF TEACHING This practice of bringing together peer review and collaborative construction of grading rubrics addresses issues raised in the literature both in terms of “the rubric debate” and critiques of peer review. It lives squarely in the post-process paradigm, not exclusively focused on process, but rather recursively focused on locally situated process and product, fostering students as good writers and the production of good writing. That is, it is a classroom adaptation of the writing center adage, “Good writers not just good writing.” Because of the necessity of working through the “meta” of writing at various stages, it demystifies good writing: it’s not something that we can’t specify, some magical quality or skill. This demystification works for both more- and less-skilled writers. It may be that less-skilled writers apply the rubric mechanically, as rules to follow, and more skilled writers can use it as a set of guidelines to which they can fluidly respond. “In short, [co-created rubrics do] not replace engaged response; [they are] a tool for generating more of it” (Turley and Gallagher 92). In a very practical way, except of course for the initial drafting and later revising, all of this can be done in one fifty minute class period, once teachers get good at it and students understand what they are doing. The one beauty of this system, as noted above, is that teachers’ do not then collect students’ papers for grading nor even feedback, but instead let them make revisions on their own based on “our” rubric. They don’t have to make revisions—it’s up to them. Anecdotally—and I hope to do more empirical research on this process—most do. Students have the opportunity to revise “based on the rubric we have created.” What they are often doing, though (again, more research is needed to empirically verify these observations), is responding to the kind of in-depth conversations we have had in class about writing, as well as the opportunities they have had to look at several peers’ papers. Like Nicole, who teaches high school English in a private Catholic school, and Gaetan, who teaches third grade in a suburban public school, my sense as a university teacher for ten 11 years, having done this for about half that time, is that the drafts I receive after students revise are of a far better quality than what I used to see. This practice is an innovative way of addressing one question in the literature about whether students receiving student feedback is beneficial. Here, students may receive bits of feedback on their individual papers, often on surface features, but what they are primarily doing is giving feedback—to give is better than to receive. But giving is in this instance not to improve another student’s paper, but to collaborate on a shared task, to solve a mutual problem—how should this assignment be evaluated? This practice does not demand a collaboratively produced response to the assignment, but it does demand a collaborative product—the rubric. So the collaboration is authentic, and valuable in the school context: students are the mint, they are making the money, the currency of school—grades. And yet I didn’t have to grade anything, nor respond individually to student papers. Some of the lower-performing students who used to just “not get the assignment” revise to a much closer approximation of what the assignment asks them to do. And the higher performing students end up with A’s instead of B’s. And as a teacher, I am pushed to respond to students’ needs, ideas, concerns and values. However, another aspect of this practice as a post-process approach is that it does not pretend that students are totally in control nor “the intended audience.” It keeps it real. One problem in the literature in terms of both power/authority and effectiveness of teaching involves how students might evaluate each other’s writing with a different set of standards than their teachers: “Students may likely be reinforcing each other’s abilities to write discourse for their peers, not for the academy—a sticky problem indeed, especially when teachers suggest that an appropriate audience for a particular paper might be the class itself” (Beaudin et al). Teachers, as the keepers of the keys (the graders), are the first if not only audience in almost all classroom situations. As Nicole notes above, students sometimes don’t believe it at first. “Because the classroom filled with student talk represents a marked departure from what has long been the American norm, it requires a revolution not only in the teacher's concept of 12 language learning, but also in the home and school communities that shape students' ideas concerning what it means to be in school” (DiPardo and Freedman, 144). This practice keeps us as instructors firmly and explicitly in the process; it does not abdicate authority nor pretend that power does not exist, but it is a genuine way of sharing power and authority in the classroom. Those of us who think of ourselves as critical pedagogues and/or constructivist educators need to authentically acknowledge the learning situation at hand. This practice finds the apertures and opportunities; it allows for a more realistically student centered, less-hierarchical, perhaps even more playful and resistant, classroom. Works Cited Beaudin, Andrea L., Steven J. Corbett, and Ilene W. Crawford. “Peer Pressure, Peer Power: Toward Systematic Collaborative Peer Review in the Composition and Writing Across the Curriculum Classroom.” The National Gallery of Writing. National Council of Teachers of English. 2009. Web. 1 Dec. 2010. Belcher, Lynn. “Peer Review and Response: A Failure of the Process Paradigm as Viewed From the Trenches.” Reforming College Composition: Writing the Wrongs. Eds. Ray Wallace, Alan Jackson, and Lewis Wallace. Westport, CT: Greenwood P, 2000. 99-111. Print. Corbett, Steven J and Juan C. Guerra. “Collaboration and Play in the Writing Classroom.” The Free Library. Farlex. 22 Dec. 2005. Web. 1 Dec. 2010. Covill, Amy E. “Comparing Peer Review and Self-Review as Ways to Improve College Students’ Writing.” Journal of Literacy Research. 42.1 (2010): 199-226. Print. DiPardo, Anne and Sarah Warshauer Freedman. “Peer Response Groups in the Writing Classroom: Theoretic Foundations and New Directions.” Review of Educational Research. 58.2 (1988): 119-149. Print. 13 Harris, Muriel. “Collaboration Is Not Collaboration Is Not Collaboration: Writing Center Tutorials vs. Peer-Response Groups.” College Composition and Communication. 43.3 (1992): 383. Print. Lundstrom, Kristi and Wendy Baker. “To give is better than to receive: The benefits of peer review to the reviewer’s own writing.” Journal of Second Language Writing. 18 (2009): 30-43. Print. Turley, Eric D. and Chris W. Gallagher. “On the Uses of Rubrics: Reframing the Great Rubric Debate.” English Journal. 97.4 (2008): 87-92. Print. 14