Mexican War and Failed Compromise pptx

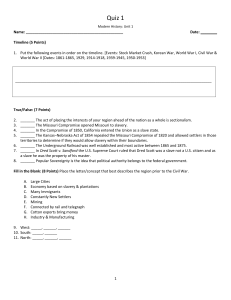

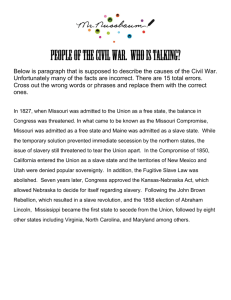

advertisement

Unit 4: A Nation Divided Lesson 3: Mexican War and Failed Compromise Bell Ringer • How does the nullification crisis show growing division between the northern and southern states? • How does the nullification crisis relate to the growing issue of slavery and sectionalism in the United States in the Early 1800s? How does this cartoon relate to sectionalism? Why did sectionalism become more severe as our territory expanded? War with Mexico • The U.S. annexes Texas, causing a boundary dispute with Mexico. • Polk ordered the army into the disputed area where Mexican troops opened fire on the Americans • Polk then asked Congress to declared war on Mexico, claiming they were the aggressor War with Mexico • The American army is ordered into Mexico, and out to California • Before the troops can reach California, a group of American settlers revolt and take the area naming it the Bear Flag Republic • In 1847, the U.S. Army enters Mexico City causing the Mexicans to surrender and ending the war War With Mexico • Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war, giving the U.S. a vast amount of land in the Southwest • The U.S. now stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean Why would this treaty cause problems with the Slavery issue? The Wilmot Proviso • During the Mexican War, in anticipation that we would win, a proposal was made in Congress for the territory gained in the Mexican War – Proposal for NO SLAVERY IN NEW TERRITORY • The proposal upset Southerners, and though it passed in the House, the Senate refused to vote on it • The Wilmot Proviso continued a north-south division over the slavery issue What do we do with the New Territory? • To counter the Wilmot Proviso and to ease tension, a proposal was made to allow the new territories to decide for themselves on the slavery issue, an idea called popular sovereignty • California applied for statehood in 1849, threatening to break the balance of free and slave states • To settle the balance, Henry Clay proposed a resolution which became known as the Compromise of 1850 (remember this from a couple of days ago?) 1828 1820 Missouri Compromise Andrew Jackson is elected/nullification crisis 1845 1846 Mexican War Annexation of Texas 1848 1850 Gold is discovered in CA Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Seneca Falls Convention 1853 CA becomes a FREE state Compromise of 1850 Gadsden Purchase The Compromise didn’t last • During the 1850s, the U.S. Government developed the plan for a Transcontinental Railroad • The RR caused the same expansion issue to be revisited againnew territories needed to become states (Nebraska Territory) Bell Ringer • What law made it a crime to help a runaway slave? • Disagreement over which political policy fueled the Nullification Crisis? • Why did thousands of people go to California in 1849? • What did the South’s heavy reliance on slaves and cotton, along with the North’s increased dependency on industry contribute to? Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854) • The Compromise of 1850 settled the issue of CA , and the Missouri Compromise settled the issue of Missouri and Maine • Does the Missouri Compromise still apply to the areas in the middle of the country? • Many people thought that if we add in TWO territories, then one would be a slave territory, and the other would be a free territory, but this did not happen • If the Missouri Compromise stood, how would the slave states feel? How about another compromise? • The Kansas-Nebraska Act • Terms of this bill: – Repeal the Missouri Compromise • Which would allow slavery in the region – Now, the slavery question was left up to the territories (Popular Sovereignty) – By this time, people’s support of slavery and opposition of slavery was extreme Bleeding Kansas • In Kansas, supporters of slavery drafted a Constitution allowing slavery – Opponents of slavery drafted a Constitution that closes slavery to the territory • Violence erupted: known as “Bleeding Kansas” • Delays statehood of Kansas Slavery and sectionalism intensifies • Many events show how the condition of the Union becomes more vulnerable during the 1850s – – – – 1852: Uncle Tom’s Cabin 1855: Bleeding Kansas 1857: Dred Scott Supreme Court Decision 1859: John Brown’s Raid I left Virginia, although I did not want to go, just as Harpers Ferry raid took place. I knew it was a crisis of great importance to our state and country and of deep interest to your political future. I must say that in my opinion events that followed and the course of public conduct and opinion, especially in Virginia, have been mismanaged and misdirected. I think that the unsound judgment, vanity and selfish policy of Governor Wise were mainly responsible for this. The Harpers Ferry affair ought to have been treated either as the insane folly of a few mistaken cranks branded fanatics or – more accurately – as the crime of a group of reckless ruffians, ready for any scheme of murder. They should have been tried and executed as criminals in the fastest possible manner. They should not have had the chance to pose as political criminals or as representatives and champions of northern sentiment. Our honorable governor could not resist making speeches about Brown’s group. By insisting that they were the leaders of an organized conspiracy in the North, he encouraged sympathy and praise from many people and respected journals of public opinion in the North. In Virginia and throughout the South, every possible effort has been made to turn these lawbreakers into political criminals. Southern opinion identifies them with the North itself, or at least the Republican Party, causing the greatest indignation against that whole section and its people. In short, with his policy of swaggering and bullying, the governor has used this whole affair for his own advantage in order to aid his vain hopes for the Presidency and to strengthen the fragment of a southern party he heads. As a result, he has called up a devil neither he nor perhaps anyone else can control. By appealing to the pride and hatred of both sections, he has brought on a real crisis dangerous to both. Answer the following: 1. Why was the raid on Harpers Ferry an event of great importance to the South? 2. Why was the even seemingly blown out of proportion to its effects? 3. On the basis of this reading, do you agree or disagree that often it is not the event itself, but the reaction of people to the even that is important? EXPLAIN. It is John Brown that we must go if we want to understand the limitations and possibilities of our situation. He was of no color, John Brown, of no race or age. He was pure passion. He was basic force like the wind, rain, and fire. “A volcano beneath a mountain of snow,” someone called him. A great gaunt man with a noble head, the look of a hawk and the intensity of a saint, John Brown lived and breathed justice. As a New England businessman, he sacrificed business and profits, using his warehouse as a station on the Underground Railroad. In the 1850’s he became a fulltime friend of freedom, fighting small wars in Kansas and leading a group of Negro slaves out of Missouri. Always, everywhere, John Brown was preaching the importance of the act. “Slavery is evil,” he said, “kill it.” “But we must study the problem…..” Slavery is evil – kill it! “We will hold a conference….” Slavery is evil – kill it! “But our allies….” Slavery is evil – kill it! John Brown was scornful of conferences and study groups and graphs. “Talk, talk, talk,” he said. Women were suffering, children were dying – and grown men were talking. Slavery was not a word; it was a fact, a chain, a whip, an event. It seemed obvious to John Brown that facts could be opposed only by facts, a life by a life. There was in John Brown a complete identification with the oppressed. It was his child that a slave owner was selling; his sister who was being whipped in the field; his wife who was being assaulted in the barn. It was not happening to Negroes; it was happening to him. It was said that he could not bear to hear the word “slave” spoken. John Brown was a Negro, and it was in this aspect that he suffered. More than Fredrick Douglass, more than any other Negro leader, John Brown suffered with the slave. “His zeal in the cause of freedom,” Frederick Douglass said, “was far superior to mine. Mine was as the candle’s light; his was as the burning sun. I could speak for the slave; John Brown could fight for the slave. I could live for the slave; John Brown could die for the slave.” In the end, John Brown chose a superhuman act. The act he chose – the tools, the means, the instruments – does not concern us here. His act, as it happened, was violent. But it could have been as gentle as rain in the spring. John Brown chose to attack the arsenal at Harpers Ferry, in the hope of creating a situation in which slaves all over the South would flock to him. He begged his old friend, Frederick Douglass to come with him, but Douglass insisted that the time was not right. The old white man and the young Negro argued from eight one night to three the next morning. While they argued, a tough, cynical fugitive slave named Shields Green watched and listened. After the argument, Douglass rose and asked Shields Green if he were ready to go. Green thought for a moment and then said: “I believe I’ll go with the old man.” Shields Green was in the mountains and could have escaped when federal troops closed in on John Brown. A man suggested running away, but Shields Green said: “I believe I’ll go down with the old man.” And he did – all the way to his death by hanging. Why did Green sacrifice his life? Not because he was committed to John Brown’s way but because he was committed to John Brown. In a horribly bloody and horribly real way, a prayer had been answered. He had at long last found a man, neither black nor white, who was willing to go all the way. Who? “I believe I’ll go with the old man.” Who? “A man for all seasons,” a pillar of fire by night and a cloud by day. Who? A John Brown. It may be that America can no longer produce such men. If so, all is lost. Cursed is the nation, cursed is the people, that can no longer breed its own radicals when it needs them. There was an America once that was big enough for a Brown. What happened to that America? Who killed it? We killed it, all of us, Negroes and whites, with our petty lies and our frantic flights from truth and risk and danger. We killed it, all of us, liberals and activists with the rest. It is my faith that buried somewhere deep beneath the detergents and lies is the dead body of the America that made Thomas Jefferson a lawbreaker and John Brown as martyr. Segregation is evil – kill it! “We will hold a conference…..” Segregation is evil – kill it! “But our allies….” Segregation is evil – kill it! For the Jew in Germany, the African in Salisbury, and the Negro in New York: Who? A man beyond good and evil, beyond black and white. Who? “A man for all seasons,” a pillar of fire by night and a cloud by day. Who? “ I believe I’ll go down with the old man.” Answer the following: 1. What did Bennett mean when he said that “John Brown was a Negro”? 2. Why, according to Bennett, does a nation need to produce radicals? 3. What did Bennett admire most about John Brown? Exit Ticket! • When do you think it was clear that compromises would no longer work to resolve the expansion and slavery issue in the United States?