The Problem of Enthymemes: Is There Help on

advertisement

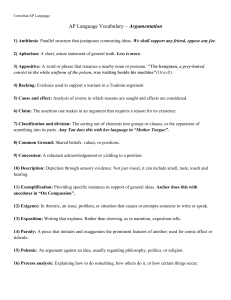

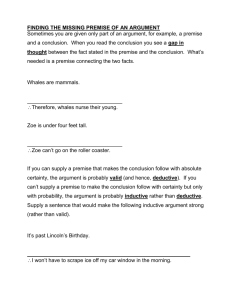

The Problem of Enthymemes: Is There Help on the Way from AI? Douglas Walton CRRAR Talk, Oct. 13, 2011 University of Windsor, Ontario CRRAR Historical Funny Business • This meaning of the term ‘enthymeme’ supposedly derives from Aristotle, and has been accepted by nearly everybody who writes on the subject (with some notable exceptions, like Sir William Hamilton), but as Burnyeat (1994) showed, it may be a historical misnomer. CRRAR Starting Definition • An enthymeme is an incomplete argument found in a text of discourse. • In many cases, the missing assumption is a premise, but sometimes it is a conclusion. • In still other cases, there is chain of arguments in which the conclusion of one argument also functions as a premise in the next one. In these cases the missing statement can be a premise as well as a conclusion. Classic Example • The classic example is the argument: all men are mortal; therefore Socrates is mortal. • As pointed out in logic textbooks, you need to insert the premise that Socrates is a man to make the argument into a valid syllogism. • But what are the grounds for inserting this proposition as a premise if it was not explicitly stated by the proponent? How Useful is Deductive Logic? • The possibility remains that we might think that we could deal with enthymemes by only using deductive logic, like syllogistic, to fill in missing premises in an incomplete argument. • This possibility has been argued against by van Eemeren and Grootendorst (1984, p. 127) using the familiar example of the argument that John is English therefore John is brave. Defeasible Generalizations • This is a textbook, so don’t expect any jokes. • According to Johnson and Blair (1983, 14), the missing premise is a generalization, ‘Textbooks don’t usually contain jokes’. • This statement is a defeasible generalization. • So deductive logic is not that useful. • We need to use defeasible argumentation schemes and generalizations. Circumlocution Avoidance • Mostly we are concerned with cases where the missing assumption is a premise. • Hence we will often speak this way, even though we know that there is a possibility that the case could be one of a missing conclusion. • This prevents excessive repetition of the qualification ‘or the conclusion’, and makes things easier for the reader to grasp. The Straw Man Problem • The problem (Burke, 1985; Gough and Tindale, 1985; Hitchcock, 1985) is that if a critic is allowed to fill in any proposition needed to make the argument valid, she may be inserting assumptions that were not meant by the proponent to be part of his or her argument. • There is the danger of committing the straw man fallacy by attributing a premise that distorts the argument in order to make it easier to refute (Scriven, 1976, pp. 85-86). Needed and Used Assumptions • Ennis (1982, pp. 63-66) drew a distinction between needed and used assumptions. • A needed assumption in an argument is a missing proposition such that (1) the argument is not structurally correct as it stands, but (2) when it is inserted, the argument becomes structurally correct (e.g. deductively valid). • A used assumption is really meant to be part of the argument by the speaker. Using Schemes to Find Missing Bits • Needed assumptions can be found by using argumentation schemes. • My doctor says I need vitamin D, therefore I need vitamin D. • The missing assumption is that my doctor is an expert in the relevant field (medicine). • You can find the missing premise by using the scheme for argument from expert opinion. • Scheme for Argument from Expert Opinion Major Premise: Source E is an expert in field F containing proposition A. Minor Premise: E asserts that proposition A (in field F) is true (false). Conclusion: A may plausibly be taken to be true (false). CRRAR Finding Used Assumptions • Finding used assumptions is much harder, because it depends on that the arguer means. • To do this we have to determine, based on the evidence we have, whether the implicit proposition is a commitment of the arguer. • This can be a hard task to compute, because we may have to draw inferences from the record of what the arguer said. Three Tools • Here we can use three additional tools. • The first of them is Gricean implicature. • The second is the notion of commitment in dialogue (Walton and Krabbe, 1995), used with the dialogue system CBVK (Walton, 2008). • Another is the notion of common knowledge. Govier and Freeman • Govier (1992, p. 120), categorized a proposition as a matter of common knowledge if it states something known by virtually everyone. • She used the examples ‘Human beings have hearts’ and ‘Many millions of civilians have been killed in twentieth-century wars’ (p. 120). • Freeman (1995, p. 269) categorized a proposition as common knowledge if many, most, or all people accept it. OMCS Common Sense System • The open mind common sense system (OMCS)includes the following statements (Singh, Lin, Mueller, Lim, Perkins and Zhu, 2002, p. 3) under the category of common knowledge. • People generally sleep at night. • If you hold a knife by its blade then it may cut you. • People pay taxi drivers to drive them places. Frames • Common knowledge can be represented in computing by what is called a frame, a data structure for representing a stereotyped situation, like going to a child’s birthday party (Minsky, 1974, p. 2). • The power of this theory lies in its inclusion of expectations and other kinds of presumptions. • A frame can be a source of common knowledge used to fill in gaps in an enthymeme. Scripts • According to Schank and Abelson (1977), common knowledge is based on a script, a body of knowledge shared by language users concerning what typically happens in certain kinds of stereotypical situations, and which enables a language user to fill in gaps in inferences not explicitly stated in a text. • Schank and Abelson used the restaurant story as an example. Jackson and Jacobs • According to Jackson and Jacobs (1980, p. 263), in order for rules of conversation to allow participants to engage in collaborative argumentation, there is a need to base many implicit assumptions on commonly shared knowledge. • These might be assumptions like, ‘Snow is white’, or ‘Los Angeles is in California’. Free Animals Example • This argument that was found in a web site called “Animal Freedom” (http://www.animalfreedom .org/english/opinion/argument/ignoring.html). • Animals in captivity are freer than in nature because there are no natural predators to kill them. The Animals Diagram Abductive Reasoning • Abductive reasoning goes backward from a given conclusion to search in a knowledge base for premises that could prove a conclusion. • The knowledge base can include explicitly stated common knowledge statements. • A knowledge-based system can search to find additional premises that that are needed to fit into argumentation schemes that can be used to prove the conclusion. The Carneades System • The Carneades argumentation system can perform abductive reasoning to find missing premises needed to prove a conclusion. • Carneades models critical questions as implicit premises of an argumentation scheme. • In addition to the ordinary premises of the scheme, there can be assumptions and exceptions. The Global Warming Example • Climate scientist Bruce, whose research is not funded by industries that have financial interests at stake, says that it is doubtful that climate change is caused by carbon emissions. • It is an exception that Bruce is not biased. • The implicit premise that Bruce is not biased is supported by the claim that his research is not funded by industries with financial interests. Six Basic Critical Questions for Argument from Expert Opinion Expertise Question: How credible is E as an expert source? Field Question: Is E an expert in the field F that A is in? Opinion Question: What did E assert that implies A? Trustworthiness Question: Is E personally reliable as a source? Consistency Question: Is A consistent with what other experts assert? Backup Evidence Question: Is E’s assertion based on evidence? Walton and Gordon (2005) • • • • • • • • Ordinary Premise: E is an expert. Ordinary Premise: E asserts that A. Ordinary Premise: A is within F. Assumption: It is assumed to be true that E is a knowledgeable expert. Assumption: It is assumed to be true that what E says is based on evidence in field F. Exception: E is not trustworthy. Exception: What E asserts is not consistent with what other experts in field F say. Conclusion: A is true. Global Warming Example Visualized in Carneades Argument Map The Yogurt Example • The ad called “In Soviet Georgia”, designed by the Burson ad agency, was run from 1975 to 1978 on TV and in magazines like Time and Newsweek. • The commercials presented shots of elderly Georgian farmers and the announcer said, “In Soviet Georgia, where they eat a lot of yogurt, a lot of people live past 100”. • Advertising Age ranked In Soviet Georgia as number 89 on its list of the best of 100 greatest advertising campaigns. Four Implicit Parts • Explicit Premise: In Soviet Georgia, they eat a lot of yogurt. • Explicit Premise: In Soviet Georgia, a lot of people live past 100. • Implicit premise: The eating of the yogurt is causing the people in Soviet Georgia to live past 100. • Implicit conclusion: If you want to live longer, you should eat yogurt. • Implicit premise: You want to live longer. • Implicit Conclusion: You should eat yogurt. The Yogurt Diagram Enthymematic Chaining • The analysis of this case it is interesting because it shows not only an ad with an implicit conclusion, but one with an implicit subconclusion used to link one part of the argument with another. • Also, two argumentation schemes can be applied to the structure of the chain of argumentation. • We essentially have to chain two arguments connected to each other because an implicit conclusion of the one argument functions as a premise supporting the one premise in the other argument. Post Hoc Fallacy? • An interesting discussion point in this example is whether the argument commits the post hoc fallacy, the error of leaping prematurely from a correlation to a causal conclusion. • There are good grounds for concluding, on the analysis above, that the argumentation in this case does commit the post hoc fallacy. • The analysis shown in the diagram along with the scheme and critical questions provide the right kind of evidence needed to support such a criticism. Exploiting Common Knowledge • This ad was successful during the days when people were aware of the longevity of the farmers in Georgia. • It was widely thought to be a remarkable phenomenon because they appeared to be no explanation of it. • The ad exploited this common knowledge successfully by allowing the reader to jump to an explanation that served the marketers of yogurt products. • The same ad would not work today, as commonly held opinions about aging and nutrition have changed. The Signal Light Example • The witness said he saw the signal light flashing on Bob's car just before the car turned. • • Therefore Bob signaled his turn. Missing Premises • Pushing the turn signal indicator is the normal way to signal a turn. • If the signal light is flashing on a car, and normally means that the driver has pushed the turn signal indicator. • If a witness makes an assertion, then the proposition that is asserted is true. • Assumption: The witness is telling the truth. • The signal light was flashing on Bob's car just before the car turned. • If the red signal light was flashing on Bob's car just before the car turned, Bob must have pushed the turn signal indicator before he turned. • Action sequence [script]: Bob moved his hand, Bob pushed the turn signal indicator, Bob activated the mechanism to make the signal light on this car flash, Bob signaled his turn. Scheme for Argument from Witness Testimony • Position to Know Premise: Witness W is in a position to know whether A is true or not. • Truth Telling Premise: Witness W is telling the truth (as W knows it). • Statement Premise: Witness W states that A is true (false). • Conclusion: Therefore (defeasibly) A is true (false). Critical Questions for Witness Testimony Scheme • Internal Consistency Question: Is what the witness said internally consistent? • Factual Consistency Question: Is what the witness said consistent with the known facts of the case (based on evidence apart from what the witness testified to)? • Consistency with Other Witnesses Question: Is what the witness said consistent with what other witnesses have (independently) testified to? • Trustworthiness Question: Is the witness personally reliable as a source? • Plausibility Question: How plausible is the statement A asserted by the witness? Exception if what the witness says is implausible. • Bias Question: Is there some kind of bias that can be attributed to the account given by the witness? • Witness Testimony Evidence: Argumentation, Artificial Intelligence and Law, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2008, p. 60. Some References M. F. Burnyeat, Enthymeme: Aristotle on the Logic of Persuasion, Aristotle’s Rhetoric: Philosophical Essays, ed. David J. Furley and Alexander Nehemas, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1994, 3-55. R. H. Ennis, Identifying Implicit Assumptions, Synthese, 51, 1982, 61-86. J. B. Freeman, The Appeal to Popularity and Presumption by Common Knowledge,'Fallacies: Classical and Contemporary Readings, ed. Hans V. Hansen and Robert C. Pinto, University Park, Pa., The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995, 263-273. J. Gough and C. Tindale, Hidden or Missing Premises, Informal Logic, 7, 1985, 99-106. T. Govier, A Practical Study of Argument, 3rd ed., Belmont, Wadsworth, 1992. J. P. Grice, Logic and Conversation, The Logic of Grammar, ed. D. Davidson and G. Harman, Encino, California, 1975, 64-75. D. Hitchcock, Enthymematic Arguments, Informal Logic, 7, 1985, 83-97. S. Jackson and S. Jacobs, Pragmatic Bases for the Enthymeme, Quarterly Journal of Speech, 66, 1980, 251-165. R. H. Johnson and J. A. Blair, Logical Self-Defense, 2nd ed., Toronto, McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 1983. M. Minsky, A Framework for Representing Knowledge, reprinted in The Psychology of Computer Vision, P. Winston, ed., McGraw Hill, 1975: available at http://web.media.mit.edu/~minsky/papers/Frames/frames.html R. C. Schank and Robert P. Abelson, Scripts, Plans, Goals and Understanding, Hillsdale, N. J., Erlbaum, 1977. M. Scriven, Reasoning, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1976. P. Singh et al., Open Mind Common Sense: Knowledge Acquisition form the General Public, Proceedings of the First International Conference on Ontologies, Databases, and Applications of Semantics for Large Scale Information Systems, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Heidelberg, Springer Verlag, 2002. F. H. van Eemeren and R. Grootendorst, Speech Acts in Argumentative Discussions, Dordrecht, Foris, 1984. D. Walton, The Three Bases for the Enthymeme: A Dialogical Theory, Journal of Applied Logic, 6, 2008, 361-379 . D. Walton and E. C. W. Krabbe, Commitment in Dialogue, Albany, SUNY Press, 1995.