Lec# 5 Opera

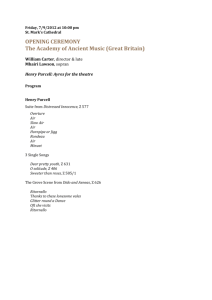

advertisement

Opera Definition • Opera, drama in which all or part of the dialogue is sung, and which contains instrumental overtures, interludes, and accompaniments. – Types of musical theater closely related to opera include musical comedy and operetta. Origins • Opera began in Italy in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. Among its precedents were many Italian madrigals of the time, in which scenes involving dialogue, but no stage action, were set to music. • Other precursors were masques, ballets de cour, intermezzi, and other Renaissance court spectacles of pageantry, music, and dance. • Opera itself was developed by a group of musicians and scholars who called themselves the Camerata (Italian for "salon"). The Camerata had two chief goals: to revive the musical style used in ancient Greek drama and to develop an alternative to the highly contrapuntal music of the late Renaissance. – Specifically, they wanted composers to pay close attention to the texts on which their music was based, to set these texts in a simple manner, and to make the music reflect, phrase by phrase, the meaning of the text. – These goals were probably characteristic of ancient Greek music, although detailed information about Greek music was not available to the Camerata (nor is it today). Henry Purcell • Many details of his life are still obscure: whether he was French or Irish in his origin, was he born in Westminster, or the exact date of birth. Whether it was 1658, or 1659, he was lucky to be born in the culminating point of English history, at the time of the restoration of the monarchy and the established Church after the Puritan Commonwealth period, when the government closed the theaters and outlawed Anglican worship. • This period of English history, opening with the accession of King Charles II and lasting from 1660 until the end of 12th century is regarded by many as the golden age of English music. Dido & Aeneas • Purcell’s opera, based on a libretto by Nahum Tate, who served as England’s poet laureate from 1692 to 1715, draws mainly upon The Aeneid’s Book Four for its plot. In order to accommodate the exigencies of the stage, in particular because it takes longer to sing a line of text than to speak it, Tate excised much of the text. Nevertheless, the basic plot remains the same: – Aeneas reaches Carthage and courts Dido; she relents, yet he leaves to fulfill his destiny in Italy. Heartbroken, she dies. • Among the elements removed due to time pressures are the characters Ascanius (Aeneas’s son, upon whom Dido transfers her lust in Virgil) and Irabus (the wrathful neighboring king and suitor of the Queen of Carthage). • Despite these strayings from Virgil, some substantive changes remain which reveal much about Purcell and his times: – No love potion spurs Dido into lust. – Aeneas vows to defy destiny. – Witches, not gods, direct their fall. Why are there differences? • • • • • • First, the absence of the Roman gods may in part be due to English theology; in this period just after the Puritan Civil War, much of England remained devoutly pious, and would find it hard to accept the gods—heathen gods though they are—as fallible. The decidedly Eastern idea of good and evil being intertwined would be foreign to the still-Puritanical English. Furthermore, the English had an obsession with witches, especially in this period of witch hunts. Additionally, the changes in the story that put more of the blame on Dido than Aeneas (in the opera, he is more stupid than uncaring) may reflect the English’s less progressive ideas about women. Again, the Puritanical tradition would support women remaining chaste, while the men would be free to “love ’em and leave ’em” just as Aeneas and his Trojan sailors do. Purcell’s chorus comments on the action much like a Greek chorus (with the character Belinda often acting like the choragos) and adds insight into the drama. Each of these elements expand the opera into far more than a simple morality play, but a complex insight into the way humans relate to each other.