Professional Mentors Welcome Back Meeting

advertisement

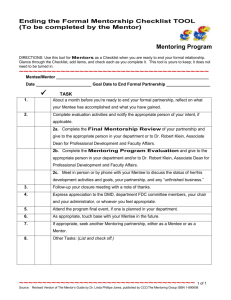

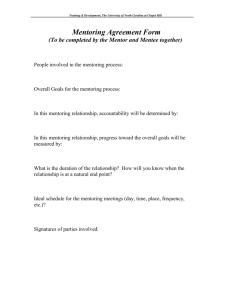

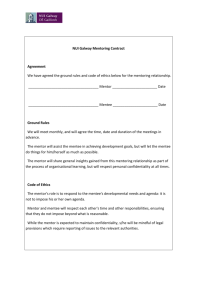

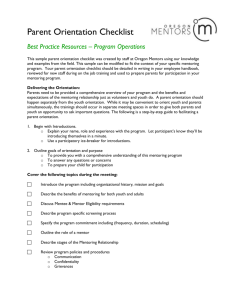

Professional Mentors Welcome Back Meeting and Training Dr. Harley E. Flack Student Mentoring Program Rowan University Adapted from The Mentor’s Guide by L. Zachary and Students Helping Students by S. Edner & F. Newton Prepared by Gardy Guiteau Assistant Director of Mentoring and Academic Enrichment Agenda Welcome and Introductions 2008-2009 in Review Why Mentoring? Defining Mentoring and the role of the Harley E. Flack Professional Mentor Developing a Mentoring Self BREAK/LUNCH Developing Key Mentoring Skills Being Aware of Your Mentee’s Life Changes Closing and Evaluations 2008-2009 in Review Successfully implemented a previously outlined fall 08 and a newly structured spring 09 calendars for both component of the program. Implemented initiatives included: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 6 academic workshops 6 service project trips 5 cultural enrichment activities 4 student development/healthy choices conversations 7 community and group building activities 5 peer-mentor training sessions Created and convened a programmatic advisory board with sixteen faculty, managers and administrators. Starting with a four-hour training on January 24th and a 1 hour training per month for throughout the spring 2009 semester, designed and implemented ongoing peer-mentor training. 2008-2009 in Review, Continued Convened a Professional Mentors’ Welcome Back Meeting at the start of the spring 2009 semester to get feedback from mentors on proposed changes and to garner buy-in for up-coming program restructuring. Restructured and implemented a multifaceted program structure which includes community building activities, ongoing peer-mentor training, and Academic Workshops designed to achieve the stated mission of the program. Began a comprehensive assessment of the program by crafting a joint program mission statement, objectives and learning outcomes; this process includes ongoing data collection of program participants’ involvement. Began the Ujima/G.I.F.T. Mentoring Initiative at Delsea Regional High School. Several Ujima participants traveled to Delsea High School at total of six times throughout the spring semester to mentor high school girls on the importance of a college education. Supported the existing mentoring efforts of the Talented Tenth at Delsea High School by helping to coordinate and co-facilitate a total of six mentoring meetings throughout the spring semester in which mentoring program male students met with Delsea High male students to discuss issues pertinent to them and the importance of a college education. 2008-2009 in Review, Continued As a result of a newly formed relationship with S.E.R.V. (Gloucester County’s domestic violence provider) mentoring program students participated in a Women’s History Month service project. Coordinated and executed an end-of-year awards banquet to celebrate and honor program participants who have been elevated to Apprentice Peer-Mentor, Peer Mentor and Project Coordinator status; as well recognize outstanding professional mentors and graduating seniors. Implemented an Exit Interview process for graduating seniors to gauge their assessment of the program. Improved the program’s marketing tools by creating a new program brochure as well as a new and improved joint Ujima and Male Mentoring webpage. Why Mentoring? Assuming that you are here because you think that mentoring is useful, in groups of four, please take 5 minutes and brainstorm the following questions: Why do you believe mentoring is a useful and important resource for college students? Why is mentoring a useful and worthwhile endeavor for professional staff? The Role of A Professional Mentor As a general rule it is assumed that in committing yourself to the mentoring program you will serves as: A special and trusting person who, knowing more through experience, commits his/her time, attention and energy to assist a less knowing student. A facilitator who creates and maintains an environment that is conducive to the learning of mentees. A facilitator of learning in such a way that knowledge, skills, or abilities connect to action in the present and possibly in the future. A developer of a learning-based mentoring relationship which fosters mentee growth, responsibility, and independence. A role model who is admired, observed, and emulated for your special qualities by participants. Adapted from the Mentor’s Guide by L. S. Zachary The Different Hats of A Professional Mentor As a Professional Mentor in the Harley E. Flack Student Mentoring Program you will wear many different hats (sometimes simultaneously). Please take a few moments to go around the room and write down on the newsprints that are posted here what you believe wearing these hast entail. Academic Advisor Career Counselor Graduate and Professional School Advisor Liaison to Academic Departments and Support Services Confidant Personal Counselor Developing a Mentoring Self Strong mentoring relationships start with a mentor who has a “clear understanding of their own personal journey” (Zachary 2000). To be a successful mentor is to be clear and aware of your own challenges and to be willing and able to share them with your mentee. As a role model mentors must be willing to allow others to bear witness to the way that they approach choice, challenges and opportunities. While I am sure that at this point in your life you have certainly given thought to your own personal and career trajectory, I will invite you in your spare time to look at The Journey Timeline, from The Mentor’s Guide by L. Zachary, and think about how you can use your experience when working with mentees. Hand-out Lunch Break Lunch is being provided. We will break for 30 minutes. As we are on a tight schedule, if you have to leave the building, please make sure that you return on time. Building the Mentoring Relationship: Four stages of the mentoring Good mentors are those who recognize and use the knowledge that mentoring relationships develop in the following cyclical stages: Preparing: This stage involves both mentor and mentee getting clear about why they are engaging one another and if they are ready and able to do so. Negotiating: In this stage the mentor and mentee set ground rules or terms of engagement to which they mutually agree. Mentoring: It is during this stage that the bulk of the work of nurturing and supporting the mentee’s growth and development as a student occurs. Closing: This stages involves evaluating, acknowledging, and celebrating successes; this stage is in itself an evolutionary process. Building the Mentoring Relationship: Time Matters Successful mentoring relationships require that both mentors and mentees commit adequate time to allow for the establishing, building, and sustaining of the mentoring relationships. This then requires the following in terms of time: Committing to be a mentor means being ready to block off a realistic amount of time to spend with each mentee. It is necessary that both mentor and mentee invest in being in contact regularly in the initial stages of the partnership. Creating mentoring meeting times that allow you and your mentee to not be rushing in or out of the meeting. Hand-out Building the Mentoring Relationship: Confidentiality is key A breach in confidentiality is sometimes one of the key reasons why a mentoring relationship falls apart. It is crucial that you develop some clear confidentiality guidelines with your mentee. But talking with a mentee about confidentiality can feel awkward and unnatural. The following are some effective ways of doing so: Approach the conversation from a place of establishing mutual respect. Start by asking your mentee how they define confidentiality. Complete an Assumption Testing Checklist about confidentiality with your mentee. Developing Key Mentoring Skills : Knowing when to breach confidentiality While confidentiality and trust are crucial to building the mentoring relationship, one key skill of the successful mentor is knowing when to breach confidentiality. Some examples of when it becomes important to do so include: Major behavioral or emotional problems Potential harm to self Potential harm to others When possible, prior to breaching confidentiality you should do the following: Get consent from the student to talk to someone else. If consent is not given and you are unsure get advise about the situation without disclosing the specific student’s identity. Developing Key Mentoring Skills : Active Listening Pay attention – Give your mentee your undivided attention. Show that you are listening – Use body language and gestures to convey your attention. Ask questions to clarify certain points. “What do you mean when you say…” “Is this what you mean?” Summarize the speaker’s comments periodically. Suspend Judgment – Interrupting is a waste of time. It frustrates the people when they are trying explaining themselves and limits full understanding of the message. Nod occasionally. Smile and use other facial expressions. Provide feedback – Our personal filters, assumptions, judgments, and beliefs can distort what we hear. As a listener, your role is to understand what is being said. This may require you to reflect what is being said and ask questions. Maintain eye contact. Put aside distracting thoughts. Don’t mentally prepare a rebuttal! Avoid being distracted by environmental factors. Allow the mentee to finish his or her sentences. Don’t interrupt with counterarguments. Respond Appropriately – Active listening is a model for respecting and understanding your mentee. The point is to gaining information and perspective. Be candid, open, and honest in your responses. Assert your opinions respectfully. Treat the other person like you would want to be treated Hand-out Developing Key Mentoring Skills: Giving effective feedback Feedback is information about performance that leads to action to affirm or develop performance. It is as much about reinforcing effective and strong performance as it is about identifying areas of potential improvement. The outcome of the feedback process should be someone who is engaged, energized and motivated to strive for increased performance. Feedback is based on a series of cycles of: Presenting a clear and specific summary of observation of behavior. Describing the impact of the behavior on others, or the situation, or how it made the observer feel. Discussing the implications of that behavior in day-to-day situations. Developing Key Mentoring Skills: Making referrals – When to refer It can be difficult to determine when to refer a student to another resource. This pressure can lead to a tendency to give quick advice or offering a solution by providing a suggestion out of your own repertoire. Often your own solution may not be the answer to your mentee’s concerns and a quick referral may feel like a brush-off or the beginning of a run-around. So what you want to do as a peermentor is: Listen carefully The first, and often the most important step, is to listen carefully and clearly so as to understand what the individual needs in the way of assistance. Remember as a peer you are perceived as an approachable, friendly source to ask for assistance. Your support, encouragement, and guidance may be sufficient to help an individual figure out what to do, but there will be times when the student’s concern is beyond your knowledge. This is the point when you consider referral. Know you limits The second most important item regarding referrals is to know your own limits for giving assistance. Trying to help a student with a serious problem when you posses minimum skill and experience can do more harm than good. So when in doubt, refer the student to a more qualified resource. Seek Consultation This step is for the helper to seek a consultation with a knowledgeable resource person to find out about options for the student being helped. The student being assisted would first be informed that you, as a peer mentor would like to consult with another source that can give suggestions or input as to the next step in assistance. By clarifying what you are seeking from consultation and getting the student’s consent, you are enabling the student to be informed and in control of this process. When seeking consultation assistance, it is important to have clear and complete information about the needs of the student you are representing. Hand-out Developing Key Mentoring Skills: Making referrals – How to refer When you refer someone to another resource, you want the referral to be seen as welcome assistance and not some sort of brush off. So be honest, direct and straightforward in your recommendation. Explain in a clear and open manner why you feel it is desirable or necessary to make a referral. Beyond honesty you need to do the following: Become knowledgeable Explain fully the services that can be obtained from the resource agency or person you are recommending. Provide confirming data about how the referral source can be useful and describe the sources qualifications or capabilities. This information can be reassuring to the student so that they will receive the help they need. Demonstrate Respect Allow the student to assume responsibility and control in making a contact or appointment. Student initiation and follow-up enhance commitment and promote a sense of independence in taking charge of the situation. Personalize the referral process It can be useful to give the student the name of a particular person who can be a direct contact. This will personalize and make the experience seem less intimidating. Be carefully though, it may be best not to provide the name of anyone who may be hard to contact or may seem less available that a general referral. Developing Key Mentoring Skills: Being aware of your Mentee’s life changes “Students in the traditional college age group… make many changes in how they think, how they feel, what they believe, what they value, and how they act in the world” (Ender & Newton 2000). As a mentor, understanding that your mentees are going through significant life changes will help you in taking an active role in helping them positively adjust to those changes. Crucial to understanding your mentees is a general understanding of how student growth occurs and in what situations. Developing Key Mentoring Skills: Understanding College Student Challenges Personal Adjustment challenges are created by the simple fact that college is a new experience involving a new environment, new people, and new responsibilities. Intellectual and Academic challenges are those related to declaring a major, signing up for courses, and overcoming limitations. Physical challenges include students’ concerns about their physical appearance or competence. Interpersonal challenges initially focus around finding a group to belong to and later involves expressing and managing feelings in relationships. Career and Lifestyle challenges involve anxiety around making decisions that may have long-term consequences on their lives. Hand-out Developing Key Mentoring Skills: Supporting Mentees through Challenges Take a genuine interest in mentee’s personal situation. Help student become aware of all of their options. Provide avenues by which students can explore alternative options. Model problem solving strategies with your mentee. Help mentees think critically about their situation by giving useful feedback. Be proactive by inviting mentees to participate in events and activities that will help them personally and academically. Closing and Evaluation Any Final Thoughts? Please complete the Training Evaluation Thank you for your attendance.