Preservation, Artifact Analysis & Curation

advertisement

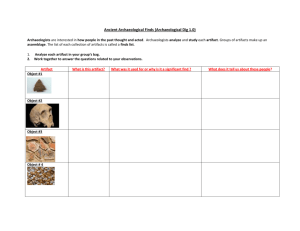

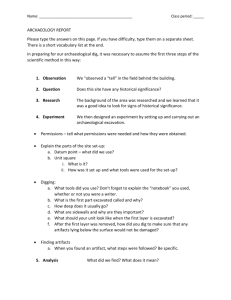

Artifact Analysis & Conservation Artifact Analysis Space, Time and Form Taxonomy, Systematics and Nomenclature Archaeological Classification Variability Artifact Analysis First described in 1909 Bruil, French Archaeologist Associated archaeology with geologic deposits classification of stone, ceramic and metal artifact types deposited by people who used them and their location in a site reflects cultural, economic,and social behavior. Artifact Analysis Sampling All excavated artifacts should be kept as a unit until everything is completely catalogued. Sampling large collections of artifacts due to time. Random Stratified Random Stratified Attributes Characteristics of artifacts Size Shape Color Material Assemblages A group of artifacts that belong together. All artifacts from a site All artifacts from a particular provenience. A particular type of artifact. Assemblage Variability Differences in artifacts through time or space. Typology Types Arbitrarily defined units of classification. Each type is separated by some difference. Lumpers and Splitters Some analysts group artifacts in fewer, more broad types-lumpers. Splitters group artifacts into more, narrowly definted types. Types Morphological Types based on form. Inherently descriptive. Temporal Change in artifacts through time. Functional Based on presumed function. Classification Classification provides a base for further analysis Fundamental analytical step Kinds of Classification Style Form Technological Quantitative vs. Qualitative Classification of Pottery Clay Pipes Uses of Classifications Culture History Reconstruct Past Lifeways Ideological/Religions Technology Materials Physical Tools Material substances object put to use Techniques Ways of making or using objects Technological Change Invention Discovery Innovation Change of new process in use Diffusion Spread of technology Studying Technology Morphological Quantitative and Qualitative Data Analysis Statistics Functional Analysis Use of artifacts Experimentation Replication/Reconstruction of artifacts Case Study: Examples from the Lost Towns of Anne Arundel Project, Maryland Excavations at Grassy Island have recovered a huge quantity of 18th century artifacts. How did we process, sort and record the garbage of a past century? What important questions did we ask to give meaning to the objects and their relationships to the site? What stories were told by the objects about the people who used them and the world they lived in? http://collections.ic.gc.ca/archaeology/second/archaeology/science/methods/lab.html Field Lab Procedures The operation of a field lab was an important part of the five seasons spent on Grassy Island. Labs were hardly glamorous - unless you fancy garages, fish plants or school rooms - but they provided a base for processing excavated artifacts. All artifacts entering the lab arrived with a provenience card assigned on the site by the archaeologist and were recorded on a daily log sheet. The provenience card had to be retained with the artifacts at all time and it was important that only one provenience be handled at a time to avoid an artifact with an archaeological "identity crisis". Different artifact categories found on Grassy Island needed different cleaning methods. Glass and most ceramic material was washed in lukewarm water using a soft brush to remove the dirt. Metal, bone and other delicate material was not placed in water but was brushed. Artifacts requiring special conservation treatment were flagged. Once the washed ceramic and glass artifacts dried, a thin coat of clear nail polish was applied on the surface on the artifact. Provenience numbers were carefully written on the dried polish with ink and a fine point dip pen. Numbers were never written on the edge of the artifact because the number had to remain visible even after mending. Metal and other artifacts which were not physically numbered were bagged with a provenience I.D. tag or label. We used eight main artifact categories for the Grassy Island excavations: 1) Ceramics; 2) Glass; 3) Metal 4) Organics (e.g., leather and bone); 5) Lithic (e.g., gunflints and projectile points); 6) Composite 7) Other (e.g., plastic) 8) Unidentified. Most of these categories have many subcategories but in a field situation most sorting is done by the major categories. After the Grassy Island artifacts were processed in the field lab they were sent to Halifax for finer sorting, mending and cataloguing. Mending and Cataloguing Most archaeological artifacts are found in fragments. The mending of the Grassy Island artifacts took many months. Think of hundreds of jigsaw puzzles, only with lots of missing pieces. First mending was done within archaeological lots (for example, 54C1) and then sherds were crossmended between lots, suboperations and even operations, establishing important connections between archaeological contexts. Once mending was completed, the mended Grassy Island fragments were catalogued. Lab researchers consulted illustrated books, contacted museums and compared their material to other collections to determine ware type, date range, function, vessel form, and country of origin (or ascription). What did they learn? Date Range Stone projectile points were discovered, revealing the presence of Aboriginal fishermen on Grassy Island over 1500 years ago. A small collection of artifacts was also excavated that suggests the seasonal use of the island by French fishermen in the 17th century. However, the vast majority of artifacts recovered from Grassy Island date to the site's occupation by New Englanders between 1720 and 1744. A few later 18th century ceramic sherds were found in the tavern cellar depression and probably relate to sporadic domestic use of the island after the destruction of the town. Trade The ceramics in particular illustrated Canso's wide-reaching trade links, with wares originating in France, the Mediterranean, the West Indies, Great Britain, Turkey, China, and New England. The presence of the French ceramic and glass wares tends to confirm other evidence of a largely illicit trade link with Louisbourg. Redwares made in the New England region are common in the collection, as would be expected given Grassy Island's New England connections. There is no evidence that pottery was manufactured locally . Social Status Artifacts excavated from the How and Heron properties suggest a comfortable, upper middle class lifestyle, especially the high percentage of expensive Chinese porcelain teawares, an 18th century status symbol. Wig curlers, stock (neckcloth) buckles, ornate sleevelinks and shoe buckles recovered from the site tell us that gentlemen living on Grassy Island continued to dress the part, despite the relative isolation of life on a windswept island. In the 18th century, homes were often places of business and it is easy to imagine a well-dressed Edward How settling accounts over French wine served in beautiful English leaded glasses. Activities Many of the artifacts recovered from Grassy Island relate to the consumption and preparation of food. A curious lack of ceramic flatware vessels suggest the residents used pewter for plates. Pewter plates were not likely to have been broken and discarded to remain as evidence in the ground. Miscellaneous activities were suggested by the presence of various tools, including a small table vise probably used to repair jewelery or other fine metals. Lead musket balls, gun parts and fish hooks were also found, as were interesting domestic artifacts that evoke 18th century life like candle- snuffers and the insert for a box clothing iron. Large quantities of clay smoking pipes were also found on Grassy Island, with telling clusters in courtyard work areas and at the site of a tavern. Indeed, the large quantities of pipes and drinking vessels helped to identify the tavern. The tavern excavations also yielded far more coarse ware vessels than fine ware vessels. A completely opposite proportion occurs in the ceramic assemblages from the How and Heron properties, indicative of the activities of a middle class domestic household versus that of a tavern. Architecture The presence of clusters of window glass helped us to locate the windows at the How property. The location of Edward How's front door was marked by its hardware, including the door knocker. A variety of building hardware was recovered from Grassy Island, dominated by thousands of wrought iron nails. Museum Reconstruction: Edward How family Experimental Archaeology Manufacturing and using tools in the present to compare to the past. Flintknapping Bone tools Metallurgy Ceramics Conservation Preserving objects after excavation. Often needing specialists and special facilities, such as cold or dry storage, humidity control, etc. CONSERVATION OF WATERLOGGED WOOD When water evaporates from wood that has been saturated for centuries and is partly decomposed, the wood shrinks and distorts. This picture shows an untreated fragment of Iron Age wood, excavated in about 1914, allowed to dry naturally. Wood is stabilized by replacing the water with impregnants that also add strength to the decayed wood. The aim is to preserve both the shape and the surface detail. It has, however, proved difficult to find preservative materials that do not themselves destroy the wood in the long run. The preferred method, at present, for conserving very decomposed wood, such as Iron Age wood from bogs, is impregnation with PEG in water solution, followed by freeze drying. Iron Age scabbard. Impregnated with sugar and a very little glycerin and freeze dried in 1994 Textiles Textiles should be removed together with the surrounding soil, so that their extraction can be completed in the workshop, under the best conditions and without using consolidants. Water soluble consolidants together with freeze drying. The textile is sometimes given a very weak lanolin treatment if it seems very brittle. Iron Age Dress Metals Iron rusts when it is exposed to water and oxygen. The process is quicker in the presence of salts, sodium chloride for example. Buried iron objects are changed partly or entirely to corrosion products, which obscure the object's original appearance. Significant traces of the original surface may lie within this corrosion. The object and the soil are impregnated with an acrylic lacquer. The surface is then exposed. The object in its bed of soil can now be displayed in a box . Metal Objects Iron pin in soil Stirrup Archaeological Site Conservation The Archaeological Conservancy http://www.americanarchaeology.com/aaabout.ht ml State Grants http://www.pr.state.az.us/partnerships/grants/gran tawards/herfun/hfawards_a.html