ch10

advertisement

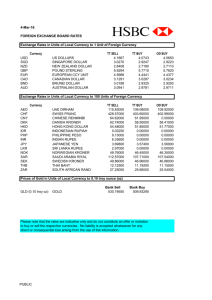

Foreign Exchange Introduction The volume of international exchange has grown tremendously since World War II Whenever an exchange takes place between residents of different countries, one kind of money has to be exchanged for another Foreign exchange rate between two currencies is determined by supply and demand established in the foreign exchange market consisting of a network of foreign exchange dealers The Equilibrium Exchange Rate The rate at which the quantity of a currency demanded is equal to the quantity supplied. At the equilibrium exchange rate, the foreign exchange market clears, meaning that the quantity of the currency demanded is exactly equal to the quantity supplied. What Determines Foreign Exchange Rates? Imports of a country give rise to a demand for foreign exchange and a supply of U.S. dollars Exports result in a supply of foreign exchange and a demand for U.S. dollars Therefore, trade of the U.S. will be a primary contributor to the demand and supply of dollars and foreign currency Balance of Payments The record of transactions between the United States and its trading partners in the rest of the world over a period of time. Trade Deficit Imports are greater than exports. Demand for foreign currency is greater than supply Result in a depreciation of the U.S. dollar Encourages exports and discourages imports Eventually the trade balance is in equilibrium at the new exchange rate. Trade Surplus Exports are greater than imports. This will result in an appreciation of the U.S. dollar and a depreciation of the foreign currency Discourages exports and encourages imports The trade will be balanced at the new exchange rate Factors that Effect Supply and Demand Relative prices of U.S. vs. foreign goods Differential inflation rates Differential interest rates Productivity Tastes for U.S. vs. foreign goods Government intervention. Relative Prices of U.S. Versus Foreign Goods Relative increase in price of U.S. goods will encourage more imports increase demand for foreign currency tends to depreciate the value of the U.S. dollar or an appreciation of the foreign currency Relative decrease in price of U.S. goods will result in an appreciation of the U.S. dollar Productivity Increased productivity in U.S. will lower price of American goods Increased demand for U.S. goods internationally Increased supply of foreign currency will appreciate the value of the dollar while foreign currency depreciates Tastes for U.S. Versus Foreign Goods Increased tastes for U.S. goods Increased demand for U.S. goods and increased supply of foreign currency Dollar appreciates relative to foreign currency How Global Investors Cause Exchange Rate Volatility Changes in the factors described above occur slowly over time, so they cannot explain the often violent short-term movement in exchange rates There is considerable day-to-day movement of U.S. dollar exchange rates versus major foreign currencies International Capital Mobility Funds flow freely across international borders and investors can purchase U.S. or foreign securities U.S. investors compare the expected return on domestic securities versus foreign securities to determine which are the most attractive Therefore, changes in preferences of U.S. versus foreign securities will result in a change in demand and supply of foreign currency and a change in the exchange rate International Capital Mobility In this case, expectations of future exchange rates play a central role in the decision process When considering investing in foreign securities to take advantage of a higher yield, must consider the expected movement of future exchange rates In order to invest in foreign securities, must first purchase foreign currency and eventually re-purchase U.S. dollars to bring currency back to U.S. International Capital Mobility It is possible that a change in the future exchange rate will offset any increased yield by holding foreign securities In fact, the international mobility of capital will often cause the change in future exchange rates that was anticipated—self-fulfilling prophesy How Global Investors Cause Exchange Rate Volatility This suggests that the equilibrium foreign exchange rate is sensitive to investor expectations of future movement in exchange rates Since these expectations might be quite unstable and susceptible to change, this may cause considerable short-term volatility in the actual exchange rates Fixed Versus Floating Exchange Rates Volatility in foreign exchange rates represents a cost of doing business internationally and imposes considerable risk on investments overseas Historically governments tried to avoid this cost by fixing exchange rates at some predetermined level Foreign Exchange Trading Regimes 1944 to 1973 Major industrial countries maintained a system of fixed exchange rates. Currency values rarely changed. 1973-present Exchange rates fluctuate daily in response to changes in supply and demand. 1944 Bretton Woods Accord Established the fixed exchange rate system. The U.S. dollar was the official reserve currency. A government was obligated to intervene in the foreign exchange markets to keep the value of its currency within a narrow range. Reserve asset balances such as gold or foreign currency holdings were key indicators of a government’s ability to keep its exchange rate stable. Floating Exchange Rates Bretton Woods System collapsed in 1971 when the U. S. suspended the international conversion of dollars to gold. Since 1973, major industrialized countries have participated in a managed float exchange rate system. If currency fluctuations become too severe and disruptive to the economy, countries may borrow funds from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to stabilize their currency. Fixed Exchange Rate System This was the system maintained globally from 1944 until the early 1970s. It came under the supervision of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) After the collapse of the fixed exchange rate system, it was resurrected with a more limited scope in 1979 for the major European countries Fixed Exchange Rate System The most recent example of a fixed exchange rate is the introduction of the Euro as the common currency of the 12 members of the European Monetary Union This new monetary union sets the exchange rate between the Euro and the member countries’ national currencies at a fixed rate Individual member countries are expected to maintain domestic economic conditions that will not cause these agreed upon exchange rates to change International Financial Crises Major problem with a fixed rate system is that it contains no self-correcting exchange rate mechanism to eliminate a country’s persistent balance-of-payment deficit A continual balance-of-payment deficit suggests domestic economic structural problems relative to the rest of the world Eventually the country will run out of international reserves and be forced to devalue which will eliminate the deficit International Financial Crises The expectation of a devaluation will cause the international financial community to take actions that will increase the likelihood of the anticipated devaluation Individuals will sell the threatened currency in the international market This increases the supply of the currency which increases the downward pressure on the value This capital flight will further deplete the country’s international reserve and speed up the devaluation Managed Float System Currently industrialized countries practice a managed float system The exchange rate is permitted to vary within a predetermined band If foreign exchange markets attempt to push the value of the currency outside the band (both above or below), central bank will intervene However, if the central bank is intervening an excessive amount, it is likely that country will be forced to devalue or revalue its currency to recognize structural changes in local economy Central Bank Intervention Direct Intervention Occurs when a country’s central bank sells some of its currency reserves for a different currency. If the Federal Reserve desired to weaken the dollar, it could sell some of its dollar reserves in exchange for foreign currencies – those currencies would appreciate against the dollar. Direct Intervention - Example On July 17, 1998, the Federal Reserve and Japan’s central bank directly intervened in the foreign exchange market by using more than $3 billion to purchase Japanese yen. The Fed was concerned that the continued depreciation of the yen would place more downward pressure on the currencies of China and Hong Kong, two currencies that had remained stable during the Asian crisis. The yen’s value increased by 5 percent on the day of the intervention. Over the next several months, the yen’s value strengthened, and in January 1999, the Fed and the Bank of Japan attempted to weaken the yen’s value by selling yen in the foreign exchange market. WSJ January 30, 2003 Japan: No Plan To Guide Yen To Specific Rate TOKYO -- Japan has no intention to guide the yen to specific level, a top Finance Ministry official said Thursday, repeating that authorities only intervene when it's necessary to calm volatile markets. Hiroshi Watanabe, the head of the International Bureau, said purchasing power parity between different countries was only one measure for currency levels. "Intervention , fundamentally, is for smoothing (volatile markets) or countering sudden moves," Watanabe said. WSJ January 31, 2003 Japan's Hush-Hush Intervention Sparks USD Rally, For Now Of DOW JONES NEWSWIRES NEW YORK -- Sometimes softly, softly does it, as the yen's decline on Friday shows. The announcement by Japan's Ministry of Finance overnight that it undertook covert currency market intervention this month to weaken the yen drove the Japanese currency to its biggest drop against the dollar in three weeks on Friday. It has left the greenback dancing around the important psychological Y120 mark, up from a session low of Y118.88 and helped fire a broad-based dollar rebound. As the world's second-biggest economy hovers on the brink of a renewed economic downturn, currency market intervention is one of the few recourses Japan's policy makers have at their disposal to encourage growth. But in the past, the Ministry of Finance - the guardian of Japan's currency policy - has been much more open with its market forays. This time, the confirmation that it has been quietly stepping into the market marks a clear - and intelligent shift that has already nervous currency traders closely second-guessing any rapid slips in the yen. For a short while at least, this new deft strategy may continue to bear fruit, U.S.-based analysts say. WSJ February 3, 2003 Dollar Gains Against Yen As Intervention Fears Loom NEW YORK -- The dollar gave a split performance, rising against the yen on anticipation that Japan may intervene again to weaken its currency, but falling against the Swiss franc on worries about prospects for a U.S.-led war with Iraq. The dollar ended the New York day lower against the euro and the Swiss franc -- a classic refuge currency in times of war -but higher against the yen and the pound. Early in the New York session, some stronger-than-expected U.S. economic reports helped improve dollar sentiment, but jitters ahead of Secretary of State Colin Powell's appearance at the U.N. Wednesday wiped out many of its gains. Indirect Intervention The Fed can attempt to lower interest rates by increasing the U.S. money supply. Lower U.S. interest rates tend to discourage foreign investors from investing in U.S. securities, thereby putting downward pressure on the dollar. Indirect Intervention during the Peso Crisis 1994 – Mexico experienced a large balance of trade deficit. On December 20, 1994, Mexico’s central bank devalued the peso by about 13%. The peso was stronger than it should have been and that encouraged Mexican firms and consumers to buy an excessive amount of imports. Stock prices plummeted as many foreign investors sold their shares and withdrew their funds from Mexico in anticipation of further devaluation in the peso. On December 22, the central bank allowed the peso to float freely, and it declined by 15%. The central bank increased interest rates as a form of indirect intervention to discourage foreign investors from withdrawing their investments in Mexico’s debt securities. Speculating with Exchange Rates The risk associated with fluctuations in the exchange rate. You have $1 million to invest. Interest rates in Germany are much higher than in the U.S., so you decide to invest in a oneyear German T-bill with a market yield of 9%. What is your holding-period yield for the year? Today: Exchange dollars for marks: 1.6 DM/$ Invest in German T-bills at 9%. In one year: Exchange marks for dollars. Suppose the dollar strengthened relative to marks: 2 DM/$. DM 1,744,000/(2 DM/$) = $872,000 Your return is not 9% but –12.8%. International Money and Capital Markets Capital mobility: International money markets: The extent to which savers can move funds across national borders for the purpose of buying financial instruments issued in other countries. Markets for cross-border exchange of financial instruments with maturities of less than one year. International capital markets: Markets for cross-border exchange of financial instruments that have maturities of a year or more. International Financial Integration International financial integration: A process through which financial markets of various nations become more alike and more interconnected. Arbitrage: Purchasing an asset at the current price in one market and profiting by selling it at a higher price in another market. Putting a Lid on Open Financial Markets: Capital Controls Capital controls: Legal restrictions on the ability of a nation’s residents to hold and trade assets denominated in foreign currencies. Malaysia Softens on Ringgit Peg 1/12/04 Malaysian Prime minister Abdullah Ahmad Badawi's new administration has wasted no time in floating a trial balloon about a potentially major economicpolicy shift -- changing the currency's peg to the dollar. Mr. Abdullah has said there is no plan to alter the ringgit's value from 3.80 to the dollar, where it has remained for more than five years, … But analysts say it is high time to consider letting the Malaysian currency strengthen against the wilting dollar and that 2004 would be a good year for a change in the fixed-rate system… Enormous changes have taken place in Asia since … then-Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad clamp the ringgit to the dollar in September 1998. The peg was one of a series of measures, including controls to keep capital from pouring out of the country, that the government imposed during the regional financial crisis, when currencies regionwide plunged and economies were thrown into deep recession. Malaysia's drastic moves were criticized by Western governments and the International Monetary Fund at the time, but many critics now concede the peg and capital controls helped stabilize the Malaysian economy. Mfg, Labor Grps Hire Law Firm On Case Vs China On Forex Jan 30, 2004 A group of 39 manufacturing, agriculture and labor trade associations and unions have hired a law firm to develop a case against China for manipulating its currency. "We believe that the Chinese practice of intervening heavily to control its currency at a significantly undervalued level - as much as 40% - against the dollar conveys an artificial trade advantage that is affecting U.S. production and jobs," Mears said. China tightly manages its currency, both through intervention and capital controls , effectively pegging it at 8.3 yuan per U.S. dollar. U.S. manufacturers want China to revalue to a stronger rate, arguing the yuan is undervalued, giving Chinese producers an unfair competitive advantage. Vehicle Currencies Vehicle currency: A commonly accepted currency that is used to denominate a transaction that does not take place in the nation that issues the currency. Almost 70 percent of U.S. paper currency and coins circulate abroad. Exchange Rate The number of units of foreign currency that can be acquired with one unit of domestic money. Appreciated – when a currency has increased in value relative to another currency. Depreciated – when a currency has decreased in value relative to another currency. Foreign Exchange Markets and Spot Exchange Rates Spot market: A market for contracts requiring the immediate sale or purchase of an asset. Spot exchange rate: The spot-market price of a currency indicating how much of one country’s currency must be given up in immediate exchange for a unit of another nation’s currency. Exchange Rate Quotations EXCHANGE RATES Wednesday, February 19, 2003 The New York foreign exchange selling rates below apply to trading among banks in amounts of $1 million and more, as quoted at 4 p.m. Eastern time by Bankers Trust Co., Dow Jones Telerate Inc., and other sources. Retail transactions provide fewer units of foreign currency per dollar. Currency U.S. $ equiv. per U.S. $ Country Wed. Wed. Australia (Dollar) .5942 1.6829 Foreign Exchange Rates Spot exchange rate vs. Forward exchange rate Appreciation vs. Depreciation 1997: Britain (Pound) 1999: Britain (Pound) The pound has depreciated by 2.51%: .5902 .6054 (1.6517-1.6943)/1.6943=-2.51% The dollar has appreciated by 2.58%: 1.6943 1.6517 (.6054-.5902)/.5902=2.58% When a country’s currency appreciates, the country’s goods abroad become more expensive and foreign goods in that country become cheaper. Conversely, when a country’s currency depreciates, its goods abroad become cheaper and foreign goods in that country become more expensive. Foreign Exchange Market Over-the-counter market Dealers (banks) Most trades involve the buying and selling of bank deposits denominated in different currencies. Transactions in excess of $1 million