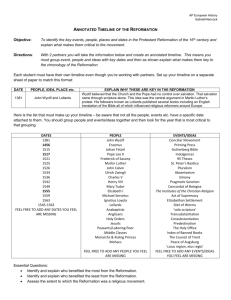

Lollards & the Reformation

advertisement

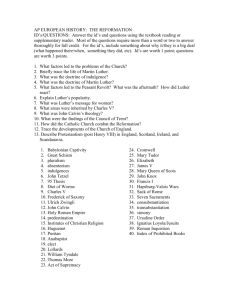

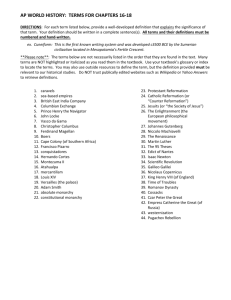

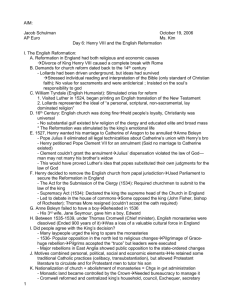

Lollards & the Reformation Religion & Religious Change in England, c.1470-1558 More opinion than evidence. Considerable overlap: Denial of transubstantiation – some Lollards went further on this than English reformers would do until the reign of Edward VI Intercession of saints Veneration of images, relics, pilgrimages Papal authority over the Church and indulgences Auricular confession of sins. Sole and supreme authority of scripture in doctrinal matters. ◦ 1) Lollardy prepare the ground for Reformation ◦ 2) A distraction (J.J. Scarisbrick). Historiography: Very little evidence for 1) James Gairdner, Lollardy & the Reformation in England: ◦ Reformation an act of state ◦ Lollards numerically insignificant. ◦ Little evidence of direct contact. J.F. Davis: ◦ Reformation long-term process ◦ Beginning with Lollardy and spreading from those roots into evangelism. But what do you do with the overlap? ◦ Little evidence of encounters/exchange – argument for ‘influence’ from silence. ◦ Europeancomparisons: Resemblances between Luther and the Hussites (C14th heresy in Bohemia) ◦ Not influenced by, even opposed in earliest years of Reformation. ◦ Calvin and Waldensianism But not grounded in, or directly influenced by. Two opinions: A.G. Dickens: ◦ ‘springboard of critical dissent from which the Protestant Reformation could overlap the walls of orthodoxy’ ◦ Some support from D. MacCulloch: ◦ Mapped Lollard centres (London, Kent, East Anglia, Bristol, Thames Valley) onto Reformation heartland. ◦ Similarities in areas untouched by either faith. ◦ Derek Plumb – Chilterns and the Thames Valley suggests points of contact. Divorced from universities. Led by lay missionaries: ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Not longer assertive and strident: Essentially illicit book-running. ◦ John Stillman/Thomas Man (burned 1518): Rumour converted 6-700. Insular – household faith for chosen. Conventicles/ private devotions. Not separate from Church. Served as Churchwardens: Saunders family of Amersham had control of the holy-water clerkship in the 1520s. Essex Lollard, William Sweeting, holywater clerk of Boxford for 7 years. ◦ John Hacker: 1520s, distribute texts London/Essex. ◦ Link communities: But no new ideas/ gathering crowds at sermons. Wycliffe’s texts not well known. Type of behaviour makes it difficult to trace: Capacity of Church to house plethora of beliefs/positions. Defining heresy problematic: ◦ Reading rare – readers stood out. ◦ Conflate eccentricity with deviance. Later Lollards: How strong was Lollardy in the early part of the C16th? 1521, Bishop Longland of Lincoln undertook a major inquest: ◦ Certainly activity against them – a reaction against Europe’s Reformation? Or indication of how strong the memory of heresy was? Or, a sign of a Church continually protecting itself against error? ◦ 35 people burned before 1533. ◦ 1511, Archbishop Warham, concerted effort in several diocese 10 burnings, 140 abjurations ◦ 400 individuals named 6 burned 50 abjured Sign knew what looking for/suspicious of an extensive network? Some evidence of strength EC16th: Revival: Increase in prosecutions and executions in the first 30 years of the C16th: ◦ Diocese of Salisbury: 16 Lollard cases 1380-1480 70 1502-24. England: 1380-1480 25 burnings 1585-1536: 50 burnings. ◦ Problem: does that mean that there were more Lollards? Or that the Church authorities were more keen to find the ones that did exist? Heresy laws: ◦ Broader context – ‘Rise of the State’: ◦ Not growing/expanding in geographical sense. ◦ If ‘reviving’ doing so in older areas, not new: Lincolnshire particularly strong. As was Berkshire, London, Colchester. No challenge to the Church in Ireland, Wales, Northern England or the West Country. ◦ Other offenders took precedent 1547, anti-Lollardy legislation replaced. Mary Tudor’s regime put Lollardy back on the map, reinforced C15th laws and orders for tracking down Lollards: ◦ ◦ Penal policy/ law code expanding under the Tudors. 1533, power of Bishops to initiate heresy trials was replaced by secular indictments. 1539 – heresy defined by statute for the first time Concern about the Mass and contestation surrounding it. Explains enquiries into Lollard heresy in Norfolk and York during 1555. As difficult for us as it was contemporaries to distinguish between old heresies and new. 1559 – legal provision against the Lollards went for good: ◦ ◦ Was that because they had disappeared; or, because the concern was now with via media Or with those who did not support the Elizabethan Reformation? Pre-Reformation revival? Lollards at Protestant sermons: ◦ East Anglia: Lollards inspired byThomas Rose, evangelical curate of Hadleigh, burnt down images at the Church of Dovercourt. ◦ Early Tudor, very strong for Lollards; later Tudor, very strong for Protestantism. ◦ Medway Valley Protestant heartland, had produced Lollards 1511-12 ◦ Bishop of Rochester – vehemently against Luther. ◦ No mention of Lollards in works. ◦ 10 executions 1504-35 – some evangelicals, others sceptics, but no evidence of Lollards. Books: ◦ Means of dissemination for both faiths – contact inevitable. ◦ Robert Barnes sold Bibles to Lollards in Essex during 1526. ◦ London Lollard John Tewkesbury burned in 1532 for possession of works by Tyndale/ Luther. Geography: ◦ Counties overlap – East Anglia. ◦ But how ‘strong’ was Lollardy? ◦ BUT: areas without Lollardy became very Protestant – Doncaster, Cambridge, Halifax. Case study – Kent: Too many exceptions for the ‘seedbed’ to really hold? Overlap with Protestantism: • Reformation amongst ‘the people’ was largely an urban phenomenon: Support of local politicians, attracted preachers. Later Lollardy a rural tradtion. ◦ Most prominent Protestants drawn from the ranks of clerics: Orthodox, not heterodox, backgrounds. What really separated reformers from previous English dissent. • Question is not why Lollards became Protestants but why Catholics did? ◦ Reformation sprang not from heresy, but from the most orthodox of the orthodox Transference of zeal. ◦ Many came to Reform via Erasmus – Tyndale, Miles Coverdale, John Frith ◦ Religious Orders – many of the most ardent Reformers former monks. John Bale, former Carmelite. 24 Protestant Bishops in 1550s, 16 had been members of religious Orders. • Cambridge University the seed bed of thought in England: Lollardy based at Oxford Cambridge had prided itself on opposing Wycliffe. Different ‘types’ of people: Not preach Wycliff to the letter. Emphasis on negation: ◦ Lordship in Grace absent. ◦ Salvation in sermons orthodox. ◦ Attacks on clergy – simony, nepotism, greed. ◦ Against cult of saints/transubstantiation/confe ssion. Where is the positive? ◦ Essentially an attack on traditional religion. Positive suggestions conventional: ◦ Follow Christ, avoid sin, perform works of mercy. Predestination: Does a ‘seedbed’ need a coherent doctrine? ◦ Case that Wycliff may have influenced Prots. ◦ But Lollards often semi-Pelagian (trusting in human capacity). ◦ Not a list or creed like Protestants. ◦ ‘Influence’ therefore more indirect than direct – not a case of transference. Beliefs & Attitudes: If historical points of contact between Lollards and Protestants can be seen as dubious, historiographical links were far more established: ◦ May have been more important. Problem: where was your Church before Luther? ◦ 1500 years since Christ, all heresy? Why would God allow that? ◦ Novelty a problem for reform – smacked of schism/heresy. Lollards a way of getting around this: ◦ One of many groups of medieval heretics whose history was re-written to overstate similarities with Protestants. ◦ John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments (1563), from conversion of Constantine in C4th to mid sixteenth, tracing unbroken line of men and women persecuted by Catholic Church as ‘Antichrist’ Visible Church of Christ in minority throughout history until Reformation, but present nonetheless. Not direct links between persons: ◦ Did not need to be ◦ That former witnesses to the Truth existed was enough. Lollards important for Protestants: ◦ Protestants re-print Lollard texts with glosses and edits to make look more ‘Protestant’ than actually were ◦ Reinvent history – Sir John Oldcastle becomes a great hero/martyr, opposing the Catholic Church as a precursor for the break with Rome. John Foxe, The Actes & Monuments (1563) Highlights the complexity of assessing Lollardy on the eve of the Reformation: ◦ 2 sets of trials: 1) Bishop John Hales 1486 2) Bishops Geoffrey Blyth 1511-1512 Many of the issues raised in this and the previous lecture: Complex relationship between heterodox and orthodox Definition of ‘Lollardy’. Complexity of Lollard belief and practice. Gets us to think about ‘the big story’. Lollards in Coventry: 3rd or 4th largest city in medieval England: Little or no Lollardy discovered 1430-80: ◦ A hub of commerce in the midlands. ◦ Especially textile manufacture. ◦ Episcopal seat. ◦ 1486 – several Lollards prosecuted. ◦ Heresies against: The Eucharist Veneration of Saints Vilification of a local shrine – the Virgin in the Tower. Lollards not dissuaded: ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ ◦ Those who abjured in 1486 still active in 1511. 1511-12 – 7 executed, 64 brought before Bishop Blyth, 110 implicated. Most abjured at the 2nd or 3rd asking. Still active in 1520 Connections to Lollards in Birmingham, Bristol, Leicester, London. Lollards in Coventry: Lollard groups were not all the same. 3 aspects made Coventry’s Lollards unusual: ◦ 1) Community practised its faith in 3 segregated groups: Married couples Men Women ◦ 2) Women played a more significant role here than elsewhere: Particularly because of the presence of elite woman, Alice Rowley, converting and maintaining female conventicles. Latterly widowed, considerable freedom. ◦ 3) Elite women participated, but men of the same social standing did not (as far as we can tell). Lollards in Coventry: Became a Lollard in 1491 under Alice Rowley’s instruction. Forced from Coventry by William Rowley – afraid – who disapproved of his wife’s activities. Used Lollard networks in Northampton, where she stayed with a leather-dresser for 5 months. Then to London where she lived with a bedder, Mr. Blackbury, whose wife was a Lollard. ◦ There – through Lollard connections – she married Thomas Wasshingbury, heretical shoemaker. ◦ Moved to Maidstone, where they were both arrested 1495. Although they abjured, they were branded with the letter ‘h’ on their jaws. Made to perform public penance in Maidstone, Canterbury, and London. Joan Warde: Husband later executed, and Joan returned to Coventry after 1495: ◦ Resumed contact Alice Rowley ◦ Became a prominent member of the community and a teacher. ◦ Appeared before the Bishops several times 1511 and 1512. ◦ Because of the very visible marking on her jaw, easy for Bishop Blythe to begin to trace her previous abjurations. ◦ Always claimed to be contrite, never denied her errors. ◦ Made to carry faggots through the street and was burned – punishment for relapsed heretic. Key: changing status of her faith, and her status within the community: ◦ A woman of low social background – unlike Alice Rowley – able to gain power and influence through heresy Leading figures in the male conventicles, and the community as a whole. Gatherings often held at Landesdale’s house: ◦ Shoemaker ◦ Lived in Coventry 18 years. ◦ A leader but spoke a lot and appeared numerous times as a witness at the trials of others. ◦ 63 ◦ Tailor ◦ Taught the heresy by Roger Brown during the 1480s. ◦ Taught many through public reading. Silkby – Blythe referred to as ‘one of the chief heretikes here’. Bishop Blythe understood as separatist community: to admit a conversation with Silksby was essentially to confess to Lollardy. Librarian and trader of books. Teacher, visited heretical priests in Leicestershire to learn more. House a sort of mini-library, centre-point of activity. Despite this, tried to impose secrecy: ◦ Passwords. ◦ Tried to prevent others from hearing him by reading in a room with the door shut. ◦ Long ‘walks in the park’ to discuss Lollard doctrine. Main point of contact with those outside of Coventry. 1511 abjured: ◦ Continued his activities, but was arrested again – with 7 others – in 1520. ◦ Fled Coventry, lived in Dumbleby for 2 years under an alias, but was finally burned in 1522. Key: Far more prominent roles in organisation and instruction, and also with the maintenance of networks. ◦ Men greater freedoms in late medieval society than women, impact on how lived in faith. Roger Landesdale & Robert Silkby: Coventry Lollards accused elites of being ‘Lollards’. Clearly discussed religion with them: ◦ Vicar, James Preston – borrowed a Lollard text from Alice Rowley ◦ Master Thomas Bayly borrowed books from Landesdale 6 years previously: Lollards thought that Bayly was ‘one of us’. ◦ Wigstons & Pysfords implicated (2 most prominent men): Conversations, rumours, discussions. One had shown ‘very beautiful books of heresy’. Not prosecuted – why? Boundaries of orthodox and heterodox are not hard and fast: ◦ Suggest, perhaps, that Lollardy had as much in common with C15th Catholicism than did against it. ◦ And WHO you were was significant in determining your religious status. Elite families: Older scholarship – these elites were unquestionably ‘Lollards’: ◦ Phrasing of wills distinctive: Indicative of personal sentiment. ◦ That that sentiment appeared to reject aspects of late medieval Catholicism, or anticipate Faith Alone: Case closed. Not quite as easy as that: ◦ Certainly placed Christ at the centre of their will bequeathments. Could be taken as a sign that rejected purgatory, rites etc. But many of these men left endowments for chantries. Elite families: Richard Coke: ◦ Fairly standard will – full trappings of medieval Catholicism. ◦ Case for Lollardy – wills homogenous, not an indicator of religious belief. ◦ Owned vernacular books, left money for an English bible in the Church. ◦ DANGER: backwards projection. ◦ Owning bible, vernacular books could be perfectly orthodox devotion. ◦ Coupled will bequests to religious orders, Masses for soul, what is more likely? How explain their interaction with Lollardy? ◦ Or the accusations that they were ‘one of us’? Not same beliefs, but same interests: ◦ A general questioning, curiosity, and thirst for literature. Difference = social status: ◦ ‘Middling sorts’: literacy and ownership of books were signs of heresy. ◦ Elites: possession of devotional works in the vernacular was an exploration of orthodox piety. Henry VIII’s government same distinctions: ◦ 1543 Act for the Advancement of True Religion forbade reading of scripture for women (nobles accepted), artisans, apprentices, journeymen, labourers Elite families: Key: many people straddled the grey area between Orthodox and heresy in C16th Coventry. ◦ Putting a label on difficult ◦ But not Lollards, or necessarily men awaiting Faith Alone. ◦ Curious, vibrant late medieval Christians associated with heretics, questioned them and – CRUCIALLY – shopped them to the Bishop. ◦ Many engaged in search for a more personal Christianity – not have to be a Lollard to do so. Social background crucial to religious experience: ◦ Women Lollards more space to act in Coventry because of Alice Rowley ◦ Roles might otherwise not have. ◦ Belonging or religious conviction? ◦ That men and women did not practice together shows how religious experience was conditioned by context as much as it was faith. Often evoked as a sign that the Reformation was not ‘top down’. But does Lollardy create a similar problem? ◦ Is awarding a relative handful of people such a considerable amount of agency in preparing the soil for the Reformation not the same as awarding it to a handful of politicians? ◦ But, small in number. ◦ Lollards may have believed in a conspiracy of the clergy against knowledge of God, but evidence not bear out. ◦ Duffy and sustained catechetical literature, prayer books, primers, satisfy thirst for knowledge and instruction. Integrated into the Church and the communities in which they lived: ◦ ‘Broad house’, vibrant late-medieval Catholicism often self-contradictory. ◦ Boundaries with those who were orthodox often very thin. Clear that there were people who denied the mediatory role of the priesthood/sacramental system/vibrant ritual practice of late medieval Catholicism: Nevertheless, an emotional and historiographical importance to Protestantism: ◦ Historical link to protest ◦ Even where actual links – in terms of people and places – lacking. Concluding thoughts: