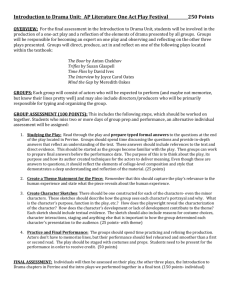

Medieval Drama

advertisement

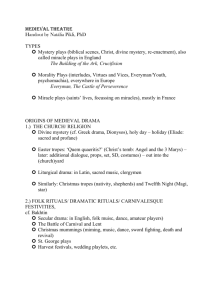

Medieval Drama Everyman Why is the period after the fall of Rome known as the “dark ages”? • The period after the fall of Rome is known as the “dark ages” because – Much political turmoil – The reliable political structure – The Church became the only stable “government” How did the Church gain so much influence in the area of drama? • The Church exerted increasing influence based on Bishop of Rome’s claim as successor to St. Peter – Established supremacy in Church matters and in secular concerns – Many Church edicts against mimes, histriones, ioculatores—terms for secular performers What fact can be found related to the early development of drama in the Church? • Little is known about the theatre between 600-1000 AD – References to actors (histriones), jugglers, rope dancers in nomadic tribes – Remnants of Roman mimes, popular pagan festivals and rites – Teutonic minstrels or troubadours (scops) became the primary preservers of tribal histories – After tribes converted to Christianity (7th-8th c), scops denounced; branded as bad as mimes • Church was the literate area of society, so what we know about theatrical performance is greater in the relgious domain – Plays by classical Roman authors were transcribed in monasteries, but were not performed – Classical Roman dramas were curated and studied for their to the learning of Latin • Church has its own form of performances in the mass, the divine office, music, processions, and Easter rituals – All these had elements of theatre, but much conducted out of sight of the general public behind the screens of the chancel – Elements of theatre found in Church services included costumes, a written script, singing, sounds, smells, and the richly decorated interior of the Church • Between 925 and 975, drama introduced into the church services, reborn in the very institution that shut it down – Church music become more elaborate with increasingly intricate variations added to the simple monophonic music known as the Gregorian chant – Elaborations known as topes (figurative/symbolic language) were added to certain significant passages • Ethelwold, bishop of Winchester, wrote instructions for the earliest recorded form of liturgical drama (part of the church service of liturgy) – At a significant point in the celebration of Matins at Easter, during the performance of the tropes, four brothers (monks) were to enact the three Maries and the angel at the empty sepulcher of Christ • Sung performance, and actors wore ecclesiastical vestments • Earliest extant [still in existence, not destroyed] drama from the Middle Ages – Four-line dramatization of the resurrection, with direction for its performance – Comes from an Easter trope (interpolation into existing text, originally lengthened musical passage with words eventually added) – Sung by a choir at first – Called the “Quem Quaeritis” – Three Maries come to the tomb of Jesus, and the angel asks them whom they are seeking: » “Whom seek ye in the tomb, O Christians?” » Jesus of Nazereth, the crucified, O heavenly beings » He is not here, he is risen as he foretold; Go and announce that he is risen from the tomb – Little by little this Easter scene was enlarged – Similar attention was given to the birth of Christ in a manager – By 975, it had become a little drama within the service, probably played by altar boys • Practice blossomed—many playlets developed dealing with Biblical themes—mostly Easter, Christmas, the 12th night (feast of the Epiphany) – Usually serious, but at Feast of Fools and the Feast of the Boy Bishops, much dancing, foolishness, and parodies of church practices occurred – Eventually other Biblical scenes and lives the saints were added • Before 1200, most drama still being done inside the Church – Plays still recited in Latin, the language of the Church – Two main areas for the performances: • Mansions—church structure usually served as mansions (choir loft might serve as heaven; the altar the tomb of Christ) • Platea—general acting area – Machinery used • Could fly Christ up to heaven or have angels come down to earth – Costumes were probably ordinary church vestments • Between 1200 and 1350, most dramas were outside – Recited in the vernacular (language of the common man), rather than Latin – Stimulus for the development of vernacular religious drama performed outside the church—the establishment of the Feast of Corpus Christi • Announced by Pope Urban IV in 1264 • Instituted by Clement V in 1311 • Required exposition of the themes of the Fall, redemption, and Judgment • Held in midsummer when days were long and the people, in general, were in festive mood – Laymen were actors—male members of the community—unpaid – Stories began to widen in scope when not part of the liturgy – Church seemed to support these dramas • While Church began to lose control over the dramas, they remained basically religious in nature. Guilds or trade/craftsmen groups took over in some cities Guilds were like trade unions combined with a social club Guilds cooperated in staging cycles of plays that dramatized the whole history of human race as then understood: creation by God, fall through the wiles of Satan, life in Old Testament times, redemption by Christ, and final judgment at the end of the world • Certain guilds retained control over certain plays/stories—usually those based in some way on that particular guild’s arts Bakers’ Guild would control the play about the Last Supper Shipwrights’ Guild would control plays about Noah and the Flood Municipalities took over productions in some cities Church still reserved the right to approve scripts, even when its role diminished Plays performed in cycles—the most famous in England: York, Chester, Coventry, and Wakefield Each guild had its own play to perform in the cycle Cycles might include up to 48 plays Comic elements appeared in plays that were otherwise very serious • Three kinds of religious plays existed. Mystery plays – about Christ or from the Old Testament (Second Shepherd’s Play is one of the most famous) Miracle plays – about lives of the saints, historical and legendary Morality plays—didactic allegories, often of common man’s struggle for salvation (Everyman is most famous) Common characteristics of religious plays Aimed to teach or reinforce Church doctrine Melodramatic: good rewarded; evil punished God and his plan were the driving forces, not the characters