3 SHEP. - University of Warwick

Shakespeare’s Bottom

Folk Comedy and Authority

Mystery plays

Who?: members of the town Guilds; paid for their performances

Where?: pageant wagons on the streets of the town

(also the streets themselves)

When?: religious festivals like Corpus Christi day or St.

George’s day

Mystery plays

Corpus Christi festival (‘Body of Christ’): officially recognised in 1311

Stories from the Bible, from the Creation to Doomsday

York, Chester, Coventry, Towneley; many others now lost

Pageant wagons (e.g. 24 at Chester, 32 at Towneley, 48 at York)

Guilds: often appropriate to story, e.g. Shipwrights present Noah’s Ark,

Bakers present the Last Supper, Pinners the crucifixion, etc.

Community celebration

Performed until late 1570s

The Second Shepherds’ Pageant:

class

1 SHEPHERD. Lord, what these weathers are cold!

And I am ill happed.

I am near-hand dold, so long have I napped;

My legs they fold, my fingers are chapped.

[…]

We are so hammed,

Fortaxed and rammed,

We are made hand-tamed

With these gentlery-men. (1-18)

1 SHEP. Patriarchs that have been, and prophets beforn,

They desired to have seen this child that is born.

They are gone full clean; that have they lorn. (692-4)

The Second Shepherds’ Pageant:

anachronism

Names: Mak, Gill, ‘Parkin, and Gibbon Waller … / And gentle John Horne’

(562-3)

MAK. Christ’s cross me speed! […] Now Christ’s holy name be us among!

(268, 278)

3 SHEP. Now trow me, if ye will – by Saint Thomas of Kent,

Either Mak or Gill was at that assent. (458-9)

1 SHEP. But, Mak, is that sooth?

Now take out that Southern tooth,

And set in a turd! (214-16)

1 SHEP. I thought that we laid us full near England. (353)

The Second Shepherds’ Pageant:

the trickster

MAK. Lord, what they sleep hard! – that may ye all hear.

Was I never a shepherd, but now I will lere… (287-8)

MAK. Do way!

I am worthy my meat,

For in a strait I can get

More than they that swink and sweat

All the day long. (309-12)

The Second Shepherds’ Pageant:

burlesque

3 SHEP. Mak, take it to no grief, if I come to thy bairn.

MAK. Nay, thou dost me great reprief, and foul hast thou farn.

3 SHEP. The child will it not grieve, that little day-starn.

Mak, with your leave, let me give your bairn

But sixpence.

MAK. Nay, do way! He sleeps.

3 SHEP. Methink he peeps.

MAK. When he wakens he weeps.

I pray you go hence.

3 SHEP. Give me leave him to kiss, and lift up the clout.

What the devil is this? He has a long snout! (575-85)

The Second Shepherds’ Pageant:

burlesque

MAK. Now, Lord, for thy names seven, that made both moon and starns

Well more than I can neven, thy will, Lord, of me tharns.

I am all uneven; that moves oft my harns.

Now would God I were in heaven, for there weep no bairns

So still. (190-4)

MARY. The Father of Heaven, God omnipotent,

That set all on seven, his Son has he sent.

My name could he neven, and light ere he went.

I conceived him full even through might, as he meant;

And now is he born. (737-41)

Locus and platea

In his influential study Shakespeare and the Popular

Tradition in the Theatre (1978, reprinted 1987), Robert

Weimann identified a ‘dual perspective’ in both medieval and Elizabethan drama which ‘encompasses conflicting views of experience’ (1987: 243).

Weimann analysed this in terms of locus and platea.

Locus and platea

Locus and platea

Locus

Localised setting (e.g. a palace, a house): “a rudimentary element of verisimilitude” (Weimann 1987: 75);

Mimesis;

High status characters: royalty, nobility;

Sacred;

Heightened language (usually verse);

Officially sanctioned historical narratives;

Elevation

Platea

Unlocalised setting (literally a ‘place’): “a theatrical dimension of the real world”

(Weimann 1987: 76);

Direct address and audience interaction;

Low status characters: rustics, servants;

Profane;

Vernacular language (prose);

Anachronistic subversion and reference to the present;

Debasement and satire

Locus and platea

‘What is involved is not the confrontation of the world and time of the play with that of the audience, or any serious opposition between representational and non-representational standards of acting, but the most intense

interplay of both’ (Weimann 1987: 80-1).

The De Witt drawing of the Swan

Theatre, c.

1596

The Peacham illustration of Titus Andronicus, c. 1595

Platea dramaturgy in Titus Andronicus

Enter the Clown with a basket and two pigeons in it

TITUS. News, news from heaven; Marcus, the post is come.

Sirrah, what tidings? Have you any letters?

Shall I have justice? What says Jupiter?

CLOWN. Ho, the gibbet-maker? He says that he hath taken them down again, for the man must not be hanged till the next week.

TITUS. But what says Jupiter, I ask thee?

CLOWN. Alas, sir, I know not Jupiter; I never drank with him in all my life. (4.3.77-85)

CLOWN. God and Saint Stephen give you good-e’en. (4.4.42-3)

Platea dramaturgy in Titus Andronicus

Phyllis Rackin:

‘Shakespeare locates his highborn men in a variety of historical worlds, but his commoners belong to the ephemeral present moment of theatrical performance, the modern, and socially degraded, world of the

Renaissance public theatre’ (1991: 98).

‘…women and commoners have no history because both are excluded from the aristocratic masculine world of written historical representation’ (1991: 103).

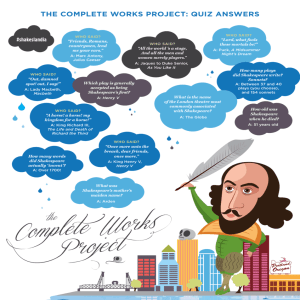

Will Kempe

Will Kempe

Played many of Shakespeare’s first great clown roles, probably including:

Dogberry

Bottom

Falstaff

Clowns like Lance, Lancelot Gobbo

Actor and shareholder in Shakespeare’s company

Famed for his improvisations: Richard Brome’s 1638 play The

Antipodes refers to Kempe as having held ‘interloquutions with the

Audients… to move mirth and laughter’ (Gurr 2002: 256).

Kempe as platea figure

Left: from the first quarto of

Much Ado About

Nothing (1600).

Below: from the second quarto of

Romeo and Juliet

(1599).

Kempe as platea figure

David Wiles points out that all of the roles Kemp is thought to have played ‘are structured in order to allow for at least one short scene in which he speaks directly to the audience’ (2005: 107).

This monologue, he notes,

‘is normally placed at the end of a scene, and thus seems to provide a format within which the clown may extemporise without risk to the rhythm of the play or direction of the narrative’ (2005: 107).

Platea dramaturgy in A Midsummer

Night’s Dream

From the first quarto of A

Midsummer

Night’s Dream

(1600).

Platea dramaturgy in A Midsummer

Night’s Dream

From the first quarto of A

Midsummer

Night’s Dream

(1600).

Platea dramaturgy in A Midsummer

Night’s Dream

Francois Laroque:

‘The function of the clown was thus to cut down intellectual pretension and to draw attention to what

Mikhail Bakhtin has called “the material bodily lower stratum,” that is, the world below the belt and the sphere of human appetite, thus allowing the spectator to distance himself/herself from high-minded activity and discourse. The opposition functions particularly well… in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where the myth of romantic love is subverted through the debunking and the bungling of Pyramus and Thisbe by the mechanicals’

(2002: 70).

‘The material bodily lower stratum’

In carnivalesque imagery, according to Mikhail Bakhtin, the human body ‘is presented not in a private, egotistic form, severed from the other spheres of life, but as something universal, representing all the people’:

‘The people’s laughter which characterized all the forms of grotesque realism from immemorial times was linked with the bodily lower stratum. Laughter degrades and materializes. […]

To degrade also means to concern oneself with the lower stratum of the body, the life of the belly and the reproductive organs; it therefore relates to acts of defecation and copulation, conception, pregnancy, and birth. Degradation digs a bodily grave for a new birth; it has not only a destructive, negative aspect, but also a regenerating one.’ (1965:

19-21)

Carnival and Elizabethan society

Elizabethan society was strictly hierarchical:

Every degree of people in their vocation, calling, and office hath appointed to them, their duty and order. Some are in high degree, some in low, some kings and princes, some inferiors and subjects, priests, and laymen, Masters and

Servants, Fathers and children, husbands and wives, rich and poor, and everyone hath need of other: so that in all things is to be lauded and praised the goodly order of god, without the which, no house, no city, no commonwealth can continue and endure or last. (From

Homily on Obedience, 1559)

Carnival and Elizabethan society

Built into the structure of Elizabethan society were a series of ‘safety valves’: periods of licence in which the strict social order would be temporarily reversed:

Shrove Tuesday

Misrule (Christmas – especially Twelfth Night)

May Day summer games

These festivals often involved an invasion of the local church or churchyard with music, singing, dancing, joking, bawdy humour, role-play and outrageous costume.

May-games

From Philip Stubbes, The Anatomie of Abuses (1583):

‘Against May, Whitsunday, or other time, old men and wives run gadding overnight to the woods, groves, hills and mountains, where they spend all night in pleasant pastimes; and in the morning they return, bringing with them birch and branches of trees, to deck their assemblies withal. … I have heard it credibly reported

(and that viva voce) by men of great gravity and reputation, that of forty, threescore, or a hundred maids going to the wood over-night, there have scarcely the third of them returned home again undefiled.’

Misrule

Stubbes again:

‘First, all the wildheads of the parish, conventing together, choose them a grand captain (of all mischief) whom they ennoble with the title of “my Lord of Misrule”, and him they crown with great solemnity, and adopt for their king. This king anointed chooseth forth twenty, forty, threescore or a hundred lusty guts, like to himself, to wait upon his lordly majesty… Then march these heathen company towards the church and churchyard, their pipers piping, their drummers thundering, their stumps dancing, their bells jingling, their handkerchiefs swinging about their heads like madmen, their hobbyhorses and other monsters skirmishing amongst the rout. And in this sort they go to the church (I say) and into the church (though the minister be at prayer or preaching) dancing and swinging their handkerchiefs over their heads in the church, like devils incarnate, with such a confused noise, that no man can hear his own voice.’

Carnival

As Michael Bristol explains:

‘Central to the experience of Carnival is a particular use of symbols, costumes and masks, in which the ordinary relationship between signifier and signified is disrupted and conventional meaning is parodied. Parody and travesty, the rude, foolish, sometimes abusive mimicry of everyday categories, create the topsy-turvy world of carnivalesque misrule.’ (Bristol 1983: 641)

Misrule in the theatre

From John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi (c. 1613):

ANTONIO. I must lie here.

DUCHESS. Must! You are a lord of misrule.

ANTONIO. Indeed, my rule is only in the night. (3.2.9-10)

From A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

OBERON. How now, mad spirit?

What nightrule now about this haunted grove?

PUCK. My mistress with a monster is in love. (3.2.4-6)

May-games in

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

LYSANDER. If thou lov’st me then,

Steal forth thy father’s house tomorrow night,

And in the wood, a league without the town,

Where I did meet thee once with Helena

To do observance to a morn of May,

There will I stay for thee. (1.1.163-8)

OBERON. …she his hairy temples then had rounded

With a coronet of fresh and fragrant flowers… (4.1.50-1)

EGEUS. I wonder of their being here together.

THESEUS. No doubt they rose up early to observe

The rite of May… (4.1.130-2)

References

Bakhtin, M. (1965) Rabelais and His World, trans. H. Iswolsky,

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Barber, C. L. (1972) Shakespeare’s Festive Comedy: A Study of Form and its

Relation to Social Custom, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bristol, M. D. (1983) ‘Carnival and the Institutions of Theatre in

Elizabethan England’, ELH, 50: 4, 637-654.

Eagleton, T. (1986) William Shakespeare, London: Basil Blackwell.

Gurr, A. (2002) Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London (2nd ed.), Cambridge:

C. U. P.

Kershaw, B. (1992) The Politics of Performance: Radical theatre as cultural

intervention, London: Routledge.

References

Laroque, F. (2002) ‘Popular Festivity’ in Leggatt, A. [ed.] The

Cambridge Companion to Shakespearean Comedy, Cambridge: C. U. P., pp. 64-78.

Palmer, D. J [ed.] (1984) Comedy: Developments in Criticism, London:

Macmillan.

Rackin, P. (1991) Stages of History: Shakespeare’s English Chronicles,

London: Routledge.

Weimann, R. (1987) Shakespeare and the Popular Tradition in the

Theater: Studies in the Social Dimension of Dramatic Form and Function,

Baltimore/London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wiles, D. (2005) Shakespeare’s Clown: Actor and Text in the Elizabethan

Playhouse, Cambridge: C. U. P.