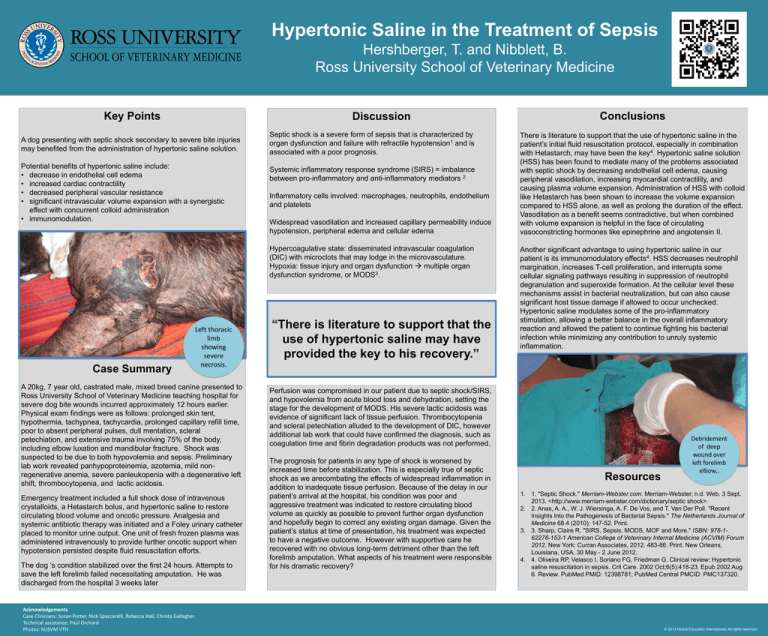

Hypertonic Saline in the Treatment of Sepsis

Hershberger, T. and Nibblett, B.

Ross University School of Veterinary Medicine

Key Points

Discussion

A dog presenting with septic shock secondary to severe bite injuries

may benefited from the administration of hypertonic saline solution.

Potential benefits of hypertonic saline include:

• decrease in endothelial cell edema

• increased cardiac contractility

• decreased peripheral vascular resistance

• significant intravascular volume expansion with a synergistic

effect with concurrent colloid administration

• immunomodulation.

Septic

shock is a severe form of sepsis that is characterized by

.

organ dysfunction and failure with refractile hypotension1 and is

associated with a poor prognosis.

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) = imbalance

between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators 2

Inflammatory cells involved: macrophages, neutrophils, endothelium

and platelets

Widespread vasodilation and increased capillary permeability induce

hypotension, peripheral edema and cellular edema

Hypercoagulative state: disseminated intravascular coagulation

(DIC) with microclots that may lodge in the microvasculature.

Hypoxia: tissue injury and organ dysfunction multiple organ

dysfunction syndrome, or MODS3.

Case Summary

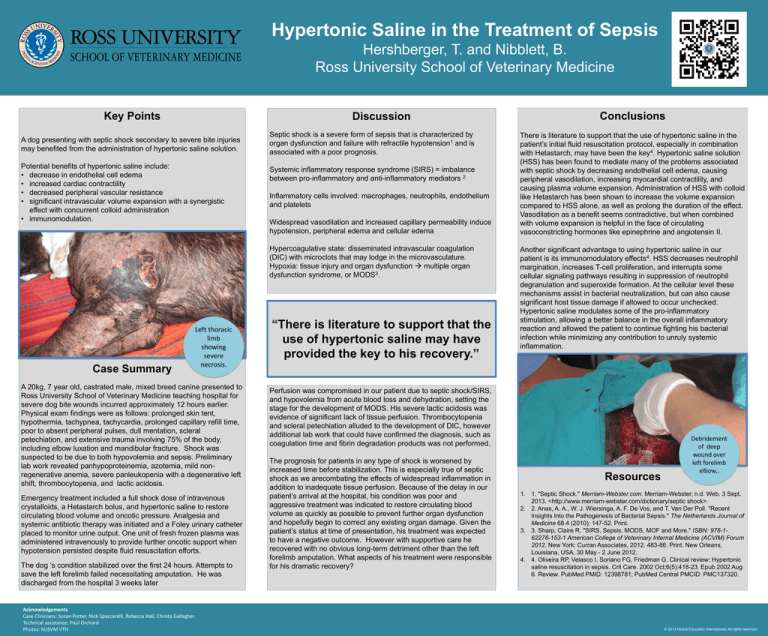

Left thoracic

limb

showing

severe

necrosis.

A 20kg, 7 year old, castrated male, mixed breed canine presented to

Ross University School of Veterinary Medicine teaching hospital for

severe dog bite wounds incurred approximately 12 hours earlier.

Physical exam findings were as follows: prolonged skin tent,

hypothermia, tachypnea, tachycardia, prolonged capillary refill time,

poor to absent peripheral pulses, dull mentation, scleral

petechiation, and extensive trauma involving 75% of the body,

including elbow luxation and mandibular fracture. Shock was

suspected to be due to both hypovolemia and sepsis. Preliminary

lab work revealed panhypoproteinemia, azotemia, mild nonregenerative anemia, severe panleukopenia with a degenerative left

shift, thrombocytopenia, and lactic acidosis.

Emergency treatment included a full shock dose of intravenous

crystalloids, a Hetastarch bolus, and hypertonic saline to restore

circulating blood volume and oncotic pressure. Analgesia and

systemic antibiotic therapy was initiated and a Foley urinary catheter

placed to monitor urine output. One unit of fresh frozen plasma was

administered intravenously to provide further oncotic support when

hypotension persisted despite fluid resuscitation efforts.

The dog ‘s condition stabilized over the first 24 hours. Attempts to

save the left forelimb failed necessitating amputation. He was

discharged from the hospital 3 weeks later

Acknowledgements

Case Clinicians: Susan Porter, Nick Spaccarelli, Rebecca Hall, Christa Gallagher

Technical assistance: Paul Orchard

Photos: RUSVM VTH

“There is literature to support that the

use of hypertonic saline may have

provided the key to his recovery.”

Conclusions

There is literature to support that the use of hypertonic saline in the

patient’s initial fluid resuscitation protocol, especially in combination

with Hetastarch, may have been the key4. Hypertonic saline solution

(HSS) has been found to mediate many of the problems associated

with septic shock by decreasing endothelial cell edema, causing

peripheral vasodilation, increasing myocardial contractility, and

causing plasma volume expansion. Administration of HSS with colloid

like Hetastarch has been shown to increase the volume expansion

compared to HSS alone, as well as prolong the duration of the effect.

Vasodilation as a benefit seems contradictive, but when combined

with volume expansion is helpful in the face of circulating

vasoconstricting hormones like epinephrine and angiotensin II.

Another significant advantage to using hypertonic saline in our

patient is its immunomodulatory effects4. HSS decreases neutrophil

margination, increases T-cell proliferation, and interrupts some

cellular signaling pathways resulting in suppression of neutrophil

degranulation and superoxide formation. At the cellular level these

mechanisms assist in bacterial neutralization, but can also cause

significant host tissue damage if allowed to occur unchecked.

Hypertonic saline modulates some of the pro-inflammatory

stimulation, allowing a better balance in the overall inflammatory

reaction and allowed the patient to continue fighting his bacterial

infection while minimizing any contribution to unruly systemic

inflammation.

Perfusion was compromised in our patient due to septic shock/SIRS,

and hypovolemia from acute blood loss and dehydration, setting the

stage for the development of MODS. His severe lactic acidosis was

evidence of significant lack of tissue perfusion. Thrombocytopenia

and scleral petechiation alluded to the development of DIC, however

additional lab work that could have confirmed the diagnosis, such as

coagulation time and fibrin degradation products was not performed.

The prognosis for patients in any type of shock is worsened by

increased time before stabilization. This is especially true of septic

shock as we arecombating the effects of widespread inflammation in

addition to inadequate tissue perfusion. Because of the delay in our

patient’s arrival at the hospital, his condition was poor and

aggressive treatment was indicated to restore circulating blood

volume as quickly as possible to prevent further organ dysfunction

and hopefully begin to correct any existing organ damage. Given the

patient’s status at time of presentation, his treatment was expected

to have a negative outcome. However with supportive care he

recovered with no obvious long-term detriment other than the left

forelimb amputation. What aspects of his treatment were responsible

for his dramatic recovery?

Resources

Debridement

of deep

wound over

left forelimb

elbow..

1. 1. "Septic Shock." Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, n.d. Web. 3 Sept.

2013. <http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/septic shock>.

2. 2. Anas, A. A., W. J. Wiersinga, A. F. De Vos, and T. Van Der Poll. "Recent

Insights Into the Pathogenesis of Bacterial Sepsis." The Netherlands Journal of

Medicine 68.4 (2010): 147-52. Print.

3. 3. Sharp, Claire R. "SIRS, Sepsis, MODS, MOF and More." ISBN: 978-162276-153-1 American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine (ACVIM) Forum

2012. New York: Curran Associates, 2012. 483-86. Print. New Orleans,

Louisiana, USA, 30 May - 2 June 2012.

4. 4. Oliveira RP, Velasco I, Soriano FG, Friedman G. Clinical review: Hypertonic

saline resuscitation in sepsis. Crit Care. 2002 Oct;6(5):418-23. Epub 2002 Aug

6. Review. PubMed PMID: 12398781; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC137320.

© 2013 Global Education International. All rights reserved.