Managing Agitation in Traumatic TBI - School of Medicine

advertisement

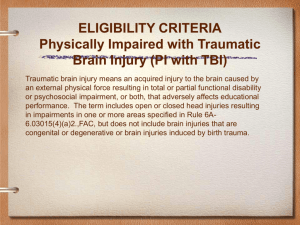

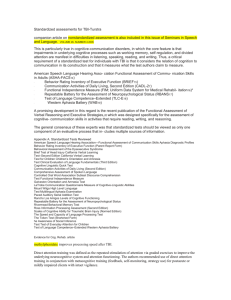

Managing Agitation in Traumatic Brain Injury Jennifer E. Marks, D.O. Department of PM&R LSUHSC TBI #1 cause of TBI is MVA Males at higher risk in all age groups Peak risk 18-25 years TBI Severe TBI estimated to be only 6% of all hospitalized brain injury cases However,the health care costs and residual deficits are much greater than with mild/moderate TBI TBI Mechanisms of injury: PRIMARY: Occur at the moment of impact SECONDARY: Triggered by primary mechanisms, cause more damage to the brain Primary Injury MechanismsTBI Most brain damage caused by accelerationdeceleration Diffuse axonal injury: Widespread stretching of axons caused by the rotation of the brain around its axis DAI may be seen on brain MRI Diffuse axonal injury Aka Shear injury Occurs in 50% of all head trauma cases Characterized clinically by LOC at time of impact Multiple b/l focal lesions throughout white matter Most commonly seen in the corpus collosum, brain stem, and frontal/temporal lobes Secondary TBI Injury Mechanisms ICH (ex. SDH) Brain edema Oxidant injury Hypoxia secondary to cerebral perfusion pressure Excitotoxicity: Neuronal damage caused by accelerated release of excitatory neurotransmitters by injured neurons Glasgow Coma Scale No direct way to measure the severity of brain injury The Glasgow Coma Scale is used to measure TBI severity The GCS evaluates the patient’s eye, motor, and verbal response The lowest score obtainable is 3, the highest is 15 The lowest post resuscitation score is the preferred value GCS Pitfalls Score can be affected by intoxication Intubation can obscure the difference between a mild and moderate TBI Also unscorable if patient cannot understand the examiner’s language Mild TBI GCS 13 or greater Equivalent to concussion Moderate TBI GCS 9-12 Follows commands Does not answer questions appropriately Severe TBI GCS < or = to 8 Patient was in a coma Permanent neurological sequelae and functional disability At least one year for maximal return to functioning Large majority of patients in rehab units TBI patient issues Spasticity Hetereotopic ossification Posttraumatic epilepsy Postraumatic hydrocephalus Cranial nerve damage Sleep disorders Dysphagia DVT Skin breakdown Post traumatic amnesia/AGITATION Definition of agitation in TBI A consensus at this time has not been reached on the exact definition of agitation. “Subtype of delirium occurring during the period of post traumatic amnesia, characterized by excessive behaviors including some combination of aggression, disinhibition, akathisia, and emotional lability.” A 1996 literature review featured in the Archives of PM&R by Sandel &Mysiw, 77:617-623 Etiology of agitation Brain trauma disrupts the catecholamine/neurotransmitter pathways: surges of norepinephrine and epinephrine have been documented in the plasma and CSF. TBI patients can also have hypothalamic dysfunction affecting temperature, blood pressure, etc. Diagnosing agitation A diagnosis of exclusion after medical and neurological conditions have been ruled out Must rule out metabolic derangement, hypothyroidism, infection/sepsis, hypoglycemia , hypoxemia, medications such as anticholinergics Drug withdrawal (ex. Sedatives, hypnotics) Diagnosing agitation continued… Neurologic complications such as seizures, hydrocephalus, IC mass lesions, and migraine are possibilities that must be investigated NEVER FORGET THAT THE PATIENT COULD BE IN PAIN ALSO!!! Tests suggested to evaluate the agitated patient CMP, Thyroid function, CBC with differential, UA, B12/folate, tox screen, Brain CT/MRI, EEG, XR (see if occult fractures/heterotopic ossification causing pain) Agitation Behavior Scale Plan for ABS to be instituted at Charity in the near future Patient given a rating of 1(absent) to 4 (severe) on 14 subcategories Subcategories include distractibility, impulsivity, violence, alterations of mood High inter-rater reliability Rancho Los Amigos Scale of Cognitive Functioning Developed at the California Hospital of the same name Rancho I: No response to any stimulation; appears to be sleeping Rancho II: Generalized Response Rancho III: Localized response Rancho Los Amigos scale (continued) **RANCHO IV: Confused, Agitated, may be aggressive Rancho V: Confused, Inapproriate, nonagitated Rancho VI: Confused, appropriate Rancho VII: Automatic, appropriate Ranch VIII: Purposeful, appropriate Management Environment Educate Staff and Family Behavior Medication Environmental Management Environmental Management FIRST REDUCE STIMULI- light, noise, distractions Patient should have a limited number of visitors at a time EVERYONE should speak in a low volume, one at a time Environmental Management To reduce patient confusion: Consistent schedule and staffing Don’t move patient to another room Reorient person frequently Behavioral Strategies Tolerate patient’s restlessness as much as possible (ex. Allow patient to pace if ambulatory) Mobile patients may need a closed unit or sensor unit for their safety Remove lines tubes ASAP Consider Craig bed or Vail bed Vail Bed Environmental Management AVOID RESTRAINTS IF AT ALL POSSIBLE Padded hand mittens if necessary Soft lap belt in the wheelchair Heavy, stable wheelchair that will not tip over Medications Since 1966, there have only been six randomized controlled trials concerning medication management of TBI agitation! Almost all studies evaluating medications have been on subjects greater than ten years old. RCT studies 1966-present Measurement and Treatment of Agitation following TBIFugate et al. Study of 129 physicians divided into experts or nonexperts surveyed. Experts either had published two or greater articles on pharmacological interventions for TBI in the last 5 years, or had > or = 70% of their practice devoted to treating TBI Fugate et al. continued Experts most frequently prescribed carbamazepine, beta blockers, TCA’s Nonexperts chose Haldol four times more frequently than experts Medications Most commonly utilized Antiepileptics Dopamine agonists (amantadine) Antidepressants (TCA’S) Antipsychotics (Haldol) Beta Blockers(Inderal) Medications for agitation Antiepileptics: Carbamazepine: Commonly utilized by rehab facilities. Some promise with agitation but only case reports have been published Phenytoin, Phenobarbitol: Not recommended secondary to interfering with cognitive function and causing excessive sedation Medications Benzodiazepines: Not recommended for long term agitation treatment due to interference with cognitive function and sedation FOR SEVERE AGITATION, Lorazepam 1-2 mg IM/IV ! Antipsychotics Ex. Haldol: The typical agents, in both human and animal studies, have been shown to cause a decline in cognitive performance (verbal ability, memory, learning, attention, spatial ability…..once the medication was stopped, cognition improved) Stanislav et al, Brain Injury 1997, p335-41 Beta blockers Two placebo-controlled, blinded studies with propanolol showed decreased agitation in patients with TBI. Also helps to control tachycardia and hypertension many TBI patients have Beta Blockers Twenty one subjects with TBI Treated with propanolol or placebo in a double-blind study In the treatment group the intensity of agitation was significantly lower, although the number of episodes was similar. The use of restraints was also significantly lower. Brooke et al., Arch Phys Med Rehabil 73, Oct 1992, 917-921 Beta Blockers Starting dose of propanolol at 20 mg BID Can use QID dosing IN ADULTS can titrate up to 60 mg/day Usually max amount 240 mg/day in adults, but doses as high as 600 mg/day have been reported As patient improves, can taper off Medication Dopamine agonists (amantadine, bromocriptine) , SSRIs, methyphenidate, and TCA’s have not been shown to control agitation successfully, but do improve alertness/initiation Conclusion More RCT studies need to be done to determine the optimum pharmacologic intervention for TBI Sources As previously stated, and…… Randall L. Braddom. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Second Edition. W. B Saunders Co. , Pennsylvania. 2000. Fleminger S., Greenwood RJ, Oliver D.L. Pharmacological management for agitation and aggression in people with acquired brain injury (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2004. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Thank you to Dr. Kiersta Kurtz-Burke, PM&R consult service staff at Charity!