Diseases of the spleen and lymph nodes

advertisement

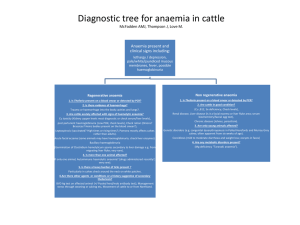

Disease of blood and blood-formation organs HAEMORRHAGE The rapid loss of whole blood from the vascular system causes peripheral circulatory failure and anaemia. Aetiology Spontaneous rupture or traumatic injury to large blood vessels are the common causes of severe haemorrhage but rapid blood loss may occur by bleeding from the mucous surfaces or by massive infestation by blood-sucking nematodes. Severe haemorrhage can thus occur in coccidiosis and salmonellosis. An important occurrence of nasal haemorrhage is in horses while racing. Extensive blood loss into tissues may also occur when there are defects of vessel walls or the clotting mechanism. Pathogenesis The major effects of haemorrhage are loss of blood volume, loss of plasma protein and loss of erythrocytes. If the rate of blood loss is rapid the loss of circulating blood volume results in peripheral circulatory failure and anaemic anoxia results from the loss of erythrocytes. Clinical Findings Pallor of the mucosae is the outstanding sign but there is in addition, weakness, staggering and recumbency, a rapid heart rate and a subnormal temperature. The respirations are deep but not dyspnoeic. Clinical Pathology Examination of the blood for haemoglobin and haematocrit levels, and the erythrocyte count are of value in indicating the severity of the blood loss and provide an index to the progress of the disease. Estimation of clotting and prothrombin times should be undertaken in cases in which unexplained spontaneous haemorrhages occur. Necropsy Findings Extreme pallor of all tissues and a thin watery appearance of the blood may be accompanied by large extravasations of blood if the haemorrhage has been internal. Where the haemorrhage has been chronic anaemia and oedema are characteristic findings. Diagnosis Other forms of peripheral circulatory failure include shock and dehydration but they can usually be differentiated on history alone. Anaemia due to other causes is not accompanied by signs of peripheral circulatory failure. Treatment All elements of the blood should be replaced and in severe cases blood transfusion is the most satisfactory treatment (1, 2, 3, 9). In large animal practice donors are usually readily available and the need for storing blood does not arise. SHOCK Secondary or surgical shock occurs some hours after trauma and is manifested by peripheral circulatory failure without evidence of fluid or blood loss. Aetiology Shock follows severe injury to tissues caused by accidental trauma, surgery, especially when the abdominal viscera are roughly handled, and occurs also after prolapse of the uterus, and when large quantities of fluid are released from body cavities. Acute infections including particularly septicaemias and peritonitis may have a similar effect. Pathogenesis Although there need be no actual blood loss there is an appreciable fall in circulating blood volume (CBV) and peripheral circulatory failure is manifested. The reason for this depression of CBV is the subject of many hypotheses. Exhaustion of adrenal cortical activity, liberation of histamine from damaged tissues resulting in peripheral vasodilatation, and overstimulation of the adrenal-sympathetic system have all been advanced as causes of traumatic shock but complete evidence is lacking to support any of them as other than contributory factors.. Clinical Findings Coldness of the skin, a subnormal temperature, rapid, shallow breathing, and a rapid heart rate accompanied by a weak pulse of small amplitude and low pressures are characteristic of shock. Venous blood pressure is greatly reduced and the veins are difficult to raise. The condition is fatal, dies in a coma. Clinical Pathology Measurement of the CBV is possible by the use of dyes or radioactive substances but the techniques are unlikely to be used in clinical practice. Haemoconcentration may or may not occur depending on whether the fluid loss is in the form of plasma or whole blood, but measurement of the haematocrit may be of value in individual cases to determine the progress of the disease.. Necropsy Findings There may be evidence of trauma and the capillaries and small vessels of the splanchnic area may be congested. Diagnosis Shock is usually anticipated when severe trauma occurs, and is diagnosed when peripheral circulatory failure is present without evidence of haemorrhage or dehydration. Treatment The primary aim in the treatment of shock is to restore the circulating blood volume, preferably by blood transfusion although the use of plasma or plasma expanders is of much greater value than in severe blood loss. OEDEMA Oedema is the excessive accumulation of fluid in tissue spaces caused by a disturbance in the mechanism of fluid interchange between capillaries, the tissue spaces and the lymphatic vessels. Aetiology Oedema results mainly from an increase in hydrostatic pressure in the capillaries, from a fall in osmotic pressure of the blood, from obstruction to lymphatic drainage or from damage to capillary walls. Increased hydrostatic pressure occurs mainly as a result of congestive heart failure but it may also occur in more limited regions such as in the portal circuit when there is hepatic fibrosis. Oedema of the udder and ventral abdominal wall occurs commonly in late pregnancy in cows and to a less extent in mares and is caused largely by foetal compression of venous drainage, although hypoproteinaemia is also thought to play a part in this form of oedema. Decreased plasma osmotic pressure is caused in most instances by a reduction in the concentration of plasma protein. Continuous haemorrhage, especially in heavy parasitic infestations, often leads to oedema. Obstruction of lymphatic flow plays a part in the production of most local oedemas caused by tumours and inflammatory swellings. Congenital lymphatic obstruction of calves and pigs and sporadic lymphangitis of horses are typical examples of obstructive oedema. Allergic oedema, manifested by urticaria, angioneurotic oedema and purpura haemorrhagica occur as a result of capillary dilation and damage caused by the local or general liberation of histamine. Fog fever probably has a similar basis. Damage to small vessels by toxins or infectious agents may also result in oedema. The oedema of septicaemic pasteurellosis of cattle, anthrax, blackleg, malignant oedema, gut oedema and mulberry heart disease of pigs and of infectious equine rhinopneumonitis, equine viral arteritis and infectious equine anaemia originates in this way. Pathogenesis At the arterial end of the capillaries the hydrostatic pressure of the blood is sufficient to overcome its osmotic pressure and fluid tends to pass into the tissue spaces. At the venous end of the capillaries the position is reversed and fluid tends to return to the vascular system. The pressure differences are not great and a small increase in hydrostatic pressure or decrease in osmotic pressure leads to failure of the fluid to return to the capillaries Clinical Findings Accumulations of oedematous transudate in subcutaneous tissues are referred to as anasarca, in the peritoneal cavity as ascites, in the pleural cavities as hydrothorax and in the pericardial sac as hydropericardium. Anasarca in large animals is usually confined to the ventral wall of the abdomen and thorax, the brisket and, if the animal is grazing, the intermandibular space. Intermandibular oedema may be less evident in animals which do not have to lower their heads to graze. Oedema of the limbs is uncommon in cattle, sheep and pigs but occurs in horses quite commonly when the venous return is obstructed or there is a lack of muscular movement. Oedematous swellings are soft, painless and pit on pressure. In ascites there is distension of the abdomen and the fluid can be detected by a fluid thrill on tactile percussion, fluid sounds on succussion and by paracentesis. A level top line of fluid may be detectable by any of these means. In the pleural cavities and pericardial sac the clinical signs produced by the fluid accumulation include restriction of cardiac movements, embarrassment of respiration and collapse of the ventral parts of the lungs. The heart sounds and respiratory sounds are muffled and the presence of fluid may be ascertained by percussion, succussion and paracentesis. Clinical Pathology Examination of a sample of fluid reveals an absence of signs of inflammation. In some instances the transudate is free of protein but in advanced cases much protein may be present because of the capillary damage which has occurred. The fluid may clot, have a high specific gravity and even contain free blood, particularly if the oedema is caused by increased hydrostatic pressure. Necropsy Findings The cause of the accumulation of fluid is obvious in many cases but estimations of the concentration of protein in the plasma may be necessary if hypoproteinaemia is thought to be the cause. If the primary cause is endothelial damage this will probably be detectable only on histological examination. Diagnosis Differentiation of the specific causes of oedema listed in aetiology above depends upon identification of the primary disease. Subcutaneous and peritoneal accumulations of urine occur when the urethra or bladder ruptures after urethral obstruction by calculi. Peritonitis, pleurisy and pericarditis are also characterized by local accumulations of fluid but toxaemia and other signs of inflammation are usually present. Treatment The treatment of oedema should be aimed at correcting the primary disease. Myocardial asthenia should be relieved by the use of digitalis, pericarditis by drainage of the sac, and hypoproteinaemia by the administration of plasma or plasma substitutes and the feeding of high quality protein. Ancillary measures include restriction of water intake and the amount of salt in the diet, the use of diuretics and aspiration of fluid. Diuretics Diseases Characterized by Abnormalities of the Cellular Elements of the Blood ANAEMIA Anaemia is defined as a deficiency of erythrocytes, or haemoglobin, per unit volume of blood. It is manifested by pallor of the mucosae, an increase in the rate and force of the heart beat and by muscle weakness. Dyspnoea at rest is not a common sign, a feature which helps to distinguish it from uncompensated heart failure. Aetiology Anaemia may be caused by excessive loss of blood by haemorrhage, or by increased destruction or the inefficient production of erythrocytes. Anaemias are therefore usually classified as haemorrhagic or haemolytic anaemia, or anaemia due to decreased production of erythrocytes. Haemorrhagic anaemia may occur after acute haemorrhage or with chronic blood loss as it occurs in parasitism, particularly haemonchosis in ruminants (1) and strongylosis in horses (2). The cause is unknown and the disease closely resembles sweet clover poisoning of newborn calves. Haemolytic anaemia is a manifestation of many infectious and non-infectious diseases. Protozoan diseases in which haemolytic anaemia occurs include babesiasis which occurs in all species, anaplasmosis of ruminants and eperythrozoonosis of swine and ruminants. In cattle other common causes are leptospirosis, bacillary haemoglobinuria, poisoning by onions or by rape and other cruciferous plants and postparturient haemoglobinuria. Calves which drink large quantities of cold water may also suffer an acute haemolytic episode and this may also occur as part of a transfusion reaction. In horses equine infectious anaemia, phenothiazine poisoning and iso-immunization haemolytic anaemia of foals are the common causes. Although uncommon, haemolytic disease of the newborn occurs also in pigs and cattle. Chronic copper poisoning in sheep causes severe haemolytic anaemia and is a major factor in the production of the clinical signs of toxaemic jaundice in this species. The same effect may be produced in cattle. Anaemia due to decreased production of erythrocytes or haemoglobin. These comprise the bulk of the naturally occurring anaemias of animals and are due in most cases to nutritional deficiency, although toxic depression of the erythropoietic activity of bone marrow may also be a cause. Nutritional deficiencies of cobalt and copper cause anaemia in ruminants and although these elements are probably necessary for erythropoiesis in other species, the requirement of them does not seem to be so great and clinical anaemia does not occur under natural conditions. A deficiency of iron in the diet causes anaemia in piglets but under natural conditions does not appear to be of major importance in the other species. Pathogenesis Irrespective of the cause of anaemia the primary abnormality of function is the anaemic anoxia which follows. In acute haemorrhagic anaemia there is in addition a loss of circulating blood volume and plasma proteins. The fluid loss is quickly repaired by equilibration with tissue fluids and by absorption and, provided haemorrhage does not continue, the plasma proteins are quickly restored to normal by synthesis in the liver. However erythropoiesis requires a longer time interval to alleviate the anaemia. Haemolytic anaemia is often sufficiently severe to cause haemoglobinuria and may result in haemoglobinuric nephrosis and depression of renal function. The primary responses to tissue anoxia caused by anaemia are an increase in cardiac output due to increases in stroke volume and heart rate, and a decrease in circulation time. Clinical Findings Pallor of the mucosae is the outstanding clinical sign but appreciable degrees of anaemia can occur without clinically visible change in mucosal or skin colour. These degrees of anaemia are usually not sufficient to cause signs of illness but they may interfere with performance, particularly in racehorses, and this aspect of equine medicine has come into prominence in recent years (5). Many horses suffer from moderate anaemia, due probably in most cases to strongylosis, and respond spectacularly to treatment with haematinic drugs. In clinical cases of anaemia there are signs of pallor, muscular weakness, depression and anorexia. The heart rate is increased, the pulse has a large amplitude and the absolute intensity of the heart sounds is markedly increased. Terminally the moderate tachycardia of the compensatory phase is replaced by a severe tachycardia, a decrease in the intensity of the heart sounds .and a weak pulse. The initial increase in intensity of heart sounds is caused by cardiac dilatation and an increase in blood pressure. Clinical Pathology Clinical signs do not appear until the haemoglobin level of the blood falls below about 50 per cent of normal. The erythrocyte count and the haematocrit are usually depressed. In haemorrhagic and haemolytic anaemias there is an increase in the number of immature red cells in the blood. The characteristic finding in anaemia caused by a deficiency of iron is hypochromasia caused by a reduction in mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; the haemoglobin level is low but the erythrocyte count may be normal. Necropsy Findings Necropsy findings include those specific to the primary cause. Findings indicative of anaemia include pallor of tissues, thin, watery blood and contraction of the spleen. Centrilobular hepatic necrosis is commonly present in cattle, and probably in other animals, if the anaemia has existed for some time (9). Diagnosis A diagnosis of anaemia is usually suggested by the obvious clinical signs. Differentiation between haemorrhagic and haemolytic anaemias and those caused by deficient production of erythrocytes or haemoglobin depends upon the history of haemorrhage, haemoglobinuria, jaundice, or diet, and upon clinical evidence of these signs. Treatment Treatment of the primary cause of the anaemia is essential. Non-specific treatment includes blood transfusion in acute haemorrhage and even in chronic anaemia of severe degree. Haematinic preparations are used in less severe cases and as supportive treatment after transfusion. Iron administered by mouth or parenterally is in common use. Preparations injected intravenously give a rapid response and intramuscular injections of organic-iron preparations give less rapid but more prolonged results. Vitamin B12 is widely used as a non- specific haematinic, particularly in horses. In extreme cases of anaemia irreversible changes caused by anoxia of kidneys and heart muscle may prevent complete recovery in spite of adequate treatment. LEUKAEMIA Leukaemia is manifested by abnormal proliferation of myelogenous or lymphatic tissues causing a marked increase in the number of circulating leucocytes. The disease is probably neoplastic in origin and is usually accompanied by enlargement of the spleen, lymph nodes and bone marrow, singly or in combination. There is sufficient evidence that some leukaemias are transmissible by means of viruses to suggest that some of those which occur commonly in livestock have a similar cause. There is as yet no concrete evidence that this is so. In leukaemic leukaemia immature leucocytes appear in the blood, in aleukaemic leukaemia the total leucocyte count may or may not be increased. In leukaemia the differential leucocyte count may be distorted, a preponderance of immature granulocytes occurring in myelogenous leukaemia and a relative increase in lymphocytes occurring in lymphatic leukaemia. There may be an accompanying aplastic anaemia if erythropoiesis is depressed by expansion of myeloid tissue in the bone marrow—a myelophthisic anaemia. Examination of smears of bone marrow has become commonplace in cases of leukaemia in large animals. Samples of bone marrow contents are easily obtained from the sternum of animals in the standing position. In the horse specimens can be readily obtained from the ilium, entrance being made through the tuber coxae (1). Bone marrow biopsy techniques have also been described for cows (3, 4) and goats (5). In farm animals the only common form of leukaemia is lymphomatosis. Myelogenous leukaemia is rare but has been recorded in all species. Erythroblastic and plasma cell tumours and monocytic leukaemia are still less frequent. Information on haemopoietic tissue tumours has been reviewed recently (2) and is not recapitulated here. When the leukaemia is leukaemic there is usually no difficulty in making a diagnosis because of the very high total white cell count, the distortion of the differential count, and the presence of immature cells. Most cases of Jymphomatosis in farm animals are subleukaemic, at least when the disease is clinically recognizable, and the differentiation from lymphadenitis may be difficult. In lymphadenitis enlargement of the nodes usually occurs rapidly and asymmetrically and the ‘enlargement may fluctuate or completely regress. The leucocytosis associated with local or generalized infections is usually less severe in degree than that of leukaemic leukaemia and the distortion of the differential count is not so marked, following a standard pattern. There is a neutrophilia with a relative increase in band forms in acute generalized or local inflammatory processes, and a lymphocytosis or monocytosis in chronic suppurative infections. LEUCOPENIA Leucopenia does not occur as a specific disease entity but is a common manifestation of a number of diseases. Virus diseases, particularly hog cholera, are frequently accompanied by a panleucopenia in the early acute stages. Leucopenia has also been observed in leptospirosis in cattle although bacterial infections are usually accompanied by a leucocytosis. Acute local inflammations may cause a transient fall in the leucocyte count because of withdrawal of the circulating cells to the septic focus. Leucopenia may also occur as part of a pancytopenia in which all cellular elements of the blood are depressed. Agents which depress the activity of the bone marrow, spleen and lymph nodes and result in pancytopenia occur in trichloroethyleneextracted soya bean meal and bracken fern. Pancytopenia occurs also in radiation disease. Chronic arsenical poisoning, and poisoning by sulphonamides, chlorpromazine and chloramphenicol cause similar blood dyscrasias in man but do not appear to have this effect in animals. The importance of leucopenia is that it reduces the resistance of the animal to bacterial infection and may be followed by a highly fatal, fulminating septicaemia. Treatment of the condition should include the administration of broad spectrum antibiotics to prevent bacterial invasion. Drugs, including pentnucleotide, which have been used to stimulate leucopoietic activity, have not been shown to materially affect most leucopenias. Diseases of the spleen and lymph nodes - Splenomegaly - Splenic Abscess - Elargement OF THE LYMPH NODES