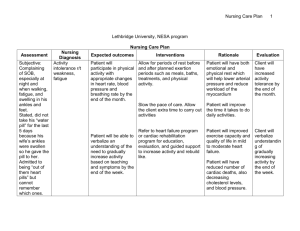

Capstone Final Paper

advertisement

Running head: COLLABORATIVE INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION Collaborative Documentation for Accurate Intake and Output in Hospitalized Patients Elise Howard The Pennsylvania State University 1 COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 2 Abstract A thorough review of the literature pertaining to the importance of intake and output shows that there is a large gap in care that persists in the acute healthcare setting: incomplete and inaccurate fluid balance documentation. A review of the relevant literature demonstrated a lack of thorough research into interventions to rectify the issue of incomplete or inaccurate intake and output documentation despite the research showing consistent results demonstrating the charting inadequacies. This study aimed to highlight the differences between nursing estimation of intake from meal trays and dietary assistants’ calculation when they take the trays out of the patients’ rooms. A pre- and post-intervention questionnaire was given to the nurses on a medical/surgical trauma step-down unit to gather information about the perception of the accuracy and effectiveness of fluid balance charts. Calculations showed that an average of 637.79 mL of fluids were undocumented resulting in about three liters of inaccurately documented fluids over the average length of stay at a hospital. Nursing questionnaires demonstrated that before the implementation of dietary and nursing staff collaboration, there was little confidence in the accuracy and effectiveness of fluid balance charts. After the intervention implementation and being shown the calculated results, perceptions on accuracy and effectiveness rose, particularly in respect to frequency of accurate intake charting. This method would utilize and already existing tool of a bedside whiteboard to help connect the patient and the nursing staff as dietary assistants could potentially write intake values on the board, thereby allowing nurses access to assessments of intake that may have previously been missed. Keywords: intake and output, documentation, fluid balance, collaboration, fluid intake-output measures COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 3 Introduction In a 2006 study by Kalisch concerning areas of frequently missed nursing care across the profession, accurate documentation of patients’ intake and output was named as one of the leading issues. It cites trays being taken away from patients’ room before nursing staff was able to document what was consumed, lack of systematic recording methods regarding water pitcher refills, as well as bathroom usage without nursing staff present. McGloin (2015) states that staff shortages, lack of staff training, and limited time as barriers to accurately recording intake and output. These missed documentations can have serious repercussions regarding patients’ health such as overlooked signs and symptoms of kidney disorders, heart failure, urinary tract infections, or perhaps even dehydration. Correct documentation of intake and output helps serve physicians and nursing staff as an ongoing indicator of illness progression or recovery (Meiner, 2002). As stated by McGloin (2015), staffing shortages play a role in accurate documentation of intake and output as the nursing staff cannot always be in the room before meal trays are taken out of the room. Therefore, this research will attempt to answer the PICO question: is the collaborative documentation of I&Os between nursing staff and dietary staff effective in accurately depicting and maintaining patients’ hydrations statuses? Many orders and prescriptions written by physicians are dependent on an accurate account of fluid balance. These order and medications may be acted upon based on faulty information in intake and output charting which may lead to negative patient outcomes like those mentioned above. Therefore, it is critical that in any hospital setting documentation of patients’ intake and output of fluids be accurately portrayed. After speaking to the staff on the third floor, South Addition, it was quickly determined that this is a perceived issue among the nursing staff and in order to obtain better patient outcomes, it should be rectified. COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 4 Orders by physicians for cardiac and renal patients often include strict observance of patients’ intake and output of fluids as well as daily weights to monitor fluid balance. Some researchers are asserting that accurate documentation of intake in output is time and resource intensive and that daily weights should be the sole order as it is less straining on resources (Wise, Mersch, Racioppi, Crosier, & Thompson, 2000). However, there are additional aims to document intake and output in patients on the 3rd floor South Addition. Not only is this a medical-surgical floor, it also functions as a step-down unit associated closely with trauma, therefore, many of the patients seen there are postoperative. This leads to the need of surveillance of fluid balance in postoperative patients to determine the presence specifically of urinary retention, as it is commonly seen after surgery as a complication of anesthesia intraoperatively as well as the opioid analgesics to control pain postoperatively (Holte, Sharrock, & Kehlet, 2002). Proper documentation of fluid balance in important especially for patients at risk for urinary retention as the staff must know when to begin the diagnostic procedures for urinary retention such as bladder scanning or straight catheterization (Johansson et al., 2012). Some research maintains that of all charting done by nursing staff, fluid balance charts were the least accurate (Armstrong-Esther, Browne, Armstrong-Esther, & Sander, 1996). While updates in computer charting has made it easier to document, it is still difficult for nursing staff to maintain accurate accounts of each of their patients. Some research suggests that increased patient participation in recording intake and output may help to increase the accuracy in documented amounts, however not all patients have the capacity to interact in such ways (Chung, Chong, & French, 2002). In order to achieve accurate documentation, some researches recommend the use of volume charts at bedside to produce more accurate representation of intake and output for a given patient (Colley, 2015). COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 5 In a variation of this bedside chart, I intend to include dietary staff in recording patients’ intake after each meal. A card with fluid containers frequently used in the meals at the hospital will be given to each of the dietary staff participating in this research. This will address the issue that not all patients will be able to be reasonably educated on the volumes of each of the fluid containers as described by Chung et al. (2002). This collaboration will utilize preexisting staff resources and potentially overcome the perception of inadequate staffing to accomplish accurate documentation of patients’ fluid balances. Literature Review Fluid balance charts have been a mainstay in acute care hospital settings and continue to be so. The issue lies in their accuracy and healthcare providers’ perceived usefulness of the charts as factual representations of patients’ fluid balance. In a 2006 study by Kalisch concerning areas of frequently missed nursing care across the nursing profession, accurate documentation of patients’ intake and output was named as one of the leading issues. It cites trays being taken away from patients’ rooms before nursing staff was able to document what was consumed, lack of systematic recording methods regarding water pitcher refills, as well as bathroom usage without nursing staff present. McGloin (2015) states that staff shortages, lack of staff training, and limited time as barriers to accurately recording intake and output. These missed documentations can have serious repercussions regarding patients’ health such as overlooked signs and symptoms of kidney disorders, heart failure, urinary tract infections, or perhaps even dehydration. This review of the literature will highlight the findings of a compilation of journal articles that deal with the importance of accurate fluid balance charting, the barriers to their accuracy and full completion, and recommendations about fluid balance charting improvements. COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 6 This research will attempt to answer if the collaborative documentation of intake and output between nursing staff and dietary staff is effective in accurately depicting and maintaining patients’ hydrations statuses. In a variation of bedside charts, I intend to include dietary staff in recording patients’ intake after each meal. A card with fluid containers frequently used in the meals at the hospital will be given to each of the dietary staff participating in this research. This will address the issue that not all patients will be able to be reasonably educated on the volumes of each of the fluid containers as described by Chung et al. (2002). This collaboration will utilize pre-existing staff resources and potentially overcome the perception of inadequate staffing to accomplish accurate documentation of patients’ fluid balances. Review of the Literature A thorough, computerized search utilizing Penn State Libraries’ compilation of multiple databases, including CINAHL, The Nursing Resource Center, and ProQuest Nursing & Allied Health Source was completed identify journal articles that have been published within the last five years, 2010-2015. Unfortunately, not much has been published about this topic in this time frame, therefore the time limit was expanded to include articles as far back as 1996 as some fundamental articles describing the problem were published during this time, though most of the articles were published within the past 10 years. The search terms utilized in the search included “intake and output,” “fluid balance,” “fluid intake-output measures,” “documentation,” “relationship based care,” and “collaboration.” the articles chosen and reviewed focused on the importance of fluid balance charting, the barriers to their accuracy and full completion, and recommendations about fluid balance charting improvements. Importance of Accurate Fluid Balance Charts COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 7 Correct documentation of intake and output helps serve physicians and nursing staff as an ongoing indicator of illness progression or recovery (Meiner, 2002). As previously cited, McGloin (2015) states that staffing shortages play a role in accurate documentation of intake and output (I&O) as the nursing staff cannot always be in the room before meal trays are taken out of the room. Many orders and prescriptions written by physicians are dependent on an accurate account of fluid balance. These orders and medications may be acted upon based on faulty information in intake and output charting which may lead to negative patient outcomes like those mentioned above. Therefore, it is critical that in any hospital setting documentation of patients’ intake and output of fluids be accurately portrayed. Orders by physicians for cardiac and renal patients often include strict observance of patients’ intake and output of fluids as well as daily weights to monitor fluid balance. Some researchers are asserting that accurate documentation of intake and output is time and resource intensive and that daily weights should be the sole order as it is less straining on resources (Wise, Mersch, Racioppi, Crosier, & Thompson, 2000). However, there are additional aims to document intake and output in patients on the 3rd floor South Addition on which I am conducting my research. Not only is this a medical-surgical floor, it also functions as a step-down unit associated closely with trauma, therefore, many of the patients seen there are postoperative. This leads to the need of surveillance of fluid balance in postoperative patients to determine the presence specifically of urinary retention, as it is commonly seen after surgery as a complication of anesthesia intraoperatively as well as the opioid analgesics to control pain postoperatively (Holte, Sharrock, & Kehlet, 2002). Proper documentation of fluid balance is important especially for patients at risk for urinary retention as the staff must know when to begin the diagnostic procedures for urinary COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 8 retention such as bladder scanning or straight catheterization (Johansson et al., 2012). Along with the factors of anesthesia and opioid analgesics, there are many other factors that increase the risk of the development of postoperative urinary retention (POUR). These include age, gender, type of surgery, comorbidities, drugs (in addition to those mentioned above), and the duration of surgery. Knowing that there are many factors that increase the chance of patients’ developing POUR, it may increase the awareness of the importance of accurately documenting fluid balance (Baldini, Bagry, Aprikian, & Carli, 2009). Scales and Pilsworth (2008) cite that there are numerous indications for fluid balance monitoring, including: intravenous infusions, subcutaneous infusions (hypodermoclysis), enteral feeding, nasogastric tubes for aspiration or drainage, urinary catheterization, vomiting, diarrhea, wound and chest drains, and medical conditions that affect fluid balance, for example heart failure, renal failure, malnutrition, or sepsis. Finally, there may be legal repercussions due to inaccurate fluid balance charting and documentation. In a brief case study, Meiner (2002) illustrates that absence of charting or inaccurate documentation of fluid balance may lead to missed care such as fluid and electrolyte replenishment that could in turn lead to organ dysfunction like renal failure or cardiovascular disease. These missed documentations could be viewed legally as negligence should untoward patient outcomes result from them. Barriers to Fluid Balance Chart Accuracy Some research maintains that of all charting done by nursing staff, fluid balance charts were the least accurate (Armstrong-Esther, Browne, Armstrong-Esther, & Sander, 1996). While updates in computer charting has made it easier to document, it is still difficult for nursing staff to maintain accurate accounts of each of their patients. COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 9 A qualitative study conducted by Kalisch (2006) showed that there are many missed aspects of nursing care including accurate documentation of patient intake and output. The article cited many barriers to quality charting in this area: too few staff, too much time required for this intervention, poor use of existing staff resources, “it’s not my job” syndrome, ineffective delegation, habit, and denial that there is an issue to being with (Kalisch, 2006). Of note, there seems to be prevailing skepticism in terms of the accuracy of the fluid balance charts which may explain why these documentations are often incomplete or inaccurate. In a 2002 study that investigated the perceptions of the efficiency of fluid balance charting, Chung, Chong, and French found that about 45% of nurses and nearly 80% of doctors regard these charts as inaccurate. After an audit of medical charts (n = 120) totaling 649 days’ worth of fluid balance charts it was found that 132 record days were incomplete and 92 daily fluid calculations were inaccurate. This indicates that around 32% of the 24 hour fluid balance charts are useless in determining a patient’s actual fluid balance (Chung, Chong, & French, 2002). Many nurses know that documentation of output is much more difficult when the patient is incontinent. This barrier is hard to hurdle without use of briefs for weighing after the patient has been incontinent to measure with the formula of: 1 L = 1 kg (despite physiologic or pathophysiologic changes in urine concentration). Such techniques are commonly seen on pediatric floors, though rarely seen on adult floors. Additionally, briefs has been known to increase the incidence of skin breakdown especially when soiled for a length of time. In an adult population, perhaps moisture pads could be used as an alternative and measured to account for incontinent urinary output (Galen, 2015). Another barrier stated in an article by Chung, Chong, and French (2002) is that some patients do not have the capacity or are not reasonably educated enough on the topic to COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 10 accurately describe what they have consumed and therefore, closer attention must be paid to recording intake and output based on reliable observers. Recommendations Some research suggests that increased patient participation in recording intake and output may help to increase the accuracy in documented amounts, however not all patients have the capacity to interact in such ways (Chung, Chong, & French, 2002). In order to achieve accurate documentation, some researchers recommend the use of volume charts at bedside to produce more accurate representation of intake and output for a given patient (Colley, 2015). Scales and Pilsworth (2008) recommend that patients be continuously screened for the need of intensive monitoring of fluid balance which would hopefully decrease the amount of time spent charting on intake and output on a patient that does not necessarily need it. They also recommend that there be standard, graduated equipment for measuring fluid intake and output as well as a reference chart for staff to use to ensure accuracy. Auditing of fluid balance charts is also recommended to ensure that high quality recording is performed and maintained (Scales & Pilsworth, 2008). An article by Reid, Robb, Stone, Bowen, Baker, Irving, & Waller (2004) demonstrates that only 11 of 20 nurses received formal training and education about fluid balance and its importance in acute care settings while only 2 of 22 nursing aides had been trained. They state that in order for intake and output to be more accurate and reliable, proper education of staff must be obtained. They also recommend using signs at the bedside to denote that a particular patient has been ordered intake and output monitoring for increased awareness. An increase in patient participation (of patients who have the learning capacity) may also increase the accuracy of these records. Wakeling (2011) reiterates that increasing staff knowledge and utilizing COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 11 alternative methods for patients to self-hydrate more independently will help to make these fluid balance charts a more reliable source of information (Wakeling, 2011). Another recommendation from Galen (2015) states that utilizing the practice often found in pediatrics units of weighing moisture absorbent pads typically found under patients while in bed or sitting in a chair. Additionally, adult briefs are sometimes used and can also be weighed as a way to measure the amount of urinary incontinence in order to estimate more accurately the output for the patient. Of note, a randomized controlled trial by Bekhof, van Asperen, and Brand (2013) showed that there was no significant difference in length of hospitalization in relation to the keeping of fluid balance charts (p = 0.06) of neonates with moderate disease severity. The authors state that fluid balance charts are often imprecise and consequently are an undependable source. While this study does not address the population of interest, it is important in demonstrating just how incomplete or inaccurate the intake and output charts are. Granted, more research needs to be completed to ensure generalizability. However, it should be noted that neonates are closely monitored during feedings and if inaccuracies can be found on this patient population, there is a greater possibility that less supervised adult patients will have more inaccuracies. Lastly, the use of an evidence-based practice of a fluid balance measurement policy has been shown to increase accuracy in intake and output charts. Alexander and Allen (2011) showed increased compliance in fluid measurement documentation after the implementation of a policy that would populate an order set based on the initial physician order requiring monitoring of intake and output (Alexander & Allen, 2011). Interprofessional Collaboration COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 12 This intervention aims to utilize hospital staff to increase patient outcomes which entails interprofessional collaboration between nursing staff and dietary staff. In a study conducted by Zwarenstein and Reeves (2006), collaboration between professions will allow one profession to report to the other regarding patient care and condition, especially aspects that may go unnoticed under other conditions without collaboration. The collaborative intervention plan clearly addresses this gap in care, allowing those who deal with patient food trays to accurately report off on the intake to nursing staff. Limitations While it is known that many hospitals utilize a daily intake and output record for numerous patients, there is limited research on whether or not these charts are reliable. Recently some studies aimed to determine if there were alternative methods of observing fluid balance to replace intake and output charts, namely daily weights. A study by Schneider, Baldwin, Freitag, Glassford, and Bellomo (2012) showed that there was only a very weak correlation between body weight and fluid balance (r = 0.34, P < 0.001). This shows that while daily weights are a useful adjunct tool, fluid balance charting cannot simply be replaced. This study and others like it looking at alternative fluid balance measures are undertaken because many view the documentation of intake and output as staff-intensive and time-consuming (Schneider, et al., 2012). With that being stated, the reliability and utility of the fluid balance chart as a tool in acute care settings need to be investigated. A 2000 study by Wise et al., show that the reliability of fluid balance charting as they are currently completed fail to achieve high reliability which may be due to failure to record voids or consumption of fluids at various times throughout the day. It showed only moderate correlation between fluid balance and daily weight (r = 0.33, P = COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 13 0.004). A similar study by Eastwood (2006) demonstrates that there is poor reliability of fluid balance charting in relation to weight gain, stating that the accuracy of the chart is often in question. These results demonstrate the need for increased attention paid to the accuracy of intake and output charting. Action Plan The plan of action that was implemented to answer PICO question if the collaborative documentation of I&Os between nursing staff and dietary staff is effective in accurately depicting and maintaining patients’ hydrations statuses. The gap that exists in the documentation of intake and output was researched by involving the stakeholders of such a gap in care: nursing staff, nursing administration, medical staff, and the patients themselves. It was initiated after speaking with the nurse manager on the 3rd floor (south addition), Brian Cosner, and nursing staff on the floor about issues that were prevalent on the floor which included undocumented or inaccurately documented intake from meal trays. Also, there are professional nursing councils that acknowledge the issue, but have yet to implement a potential solution. This study will hopefully supplement the current research currently being done on the issue at the hospital and potentially provide a resolution of the problem. Methods The scope of the project was included patients that are admitted to the trauma step-down unit (3SAE/W) who have orders for intake and output. While this is an adult trauma step-down unit, it acts as a medical/surgical overflow floor, therefore a variety of patients with a myriad of acuities of illnesses. The patients seen in any hospital setting has the potential to be ordered close observation of intake and output, therefore this study can be applied to many other acute care areas. There are many individuals who worked as a team with this study to gain permission to COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 14 implement the intervention on the floor and to help work with the dietary assistants, all of whom are listed in Table 1, below. All participants were given a brief introduction to the study detailing what the study aimed to achieve and how it would be completed. This introduction can be found in Appendix B. Name Phone Unit Shift Victoria Durf (717) 531-7338 3SAE/W Days Alicia Spencer (717) 531-7338 3SAE/W Days Ashley Zipp (717) 531-7338 3SAE/W Rotating/Days Brian Conser (717) 531-0003 3SAE/W Days Lisa Black (717) 531-7338 3SAE/W Days Anthony Bughi (717) 531-7338 Dietary Days Table 1: Team member of the study Nursing Perception Questionnaires. A Likert scale-style pre-intervention questionnaire was developed by the principal researcher and was distributed to nursing staff employees caring for the patients who were order intake and output observation inquiring their overall perceptions about the accuracy and dependability of the fluid balance charting as it was before the implementation of the above intervention. A Likert scale post-intervention questionnaire utilizing the same questions as the pre-intervention questionnaire was given after the intervention has been implemented to get a sense of how the nursing staff perceived the efficacy of the intervention. Both pre- and post-intervention questionnaires can be found in Appendix B. Comparison of Fluid Balances. Those who provide the patients with food (known as dietary assistants at Hershey Medical Center) document and gave to the principal researcher, Elise Howard, the total volume (in mL) intake from each meal tray of the selected patient as they COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 15 are also the staff that remove the trays as well. The dietary assistants were provided with a card that details fluid containers commonly found on meal trays and their corresponding volumes in milliliters (mL) as a reference guide and education point. A chart review was then completed, specifically targeting the “I/O IVIEW” portion to compare the values that the nursing staff documented as what they perceived to be the patients’ intake. The goal was to determine if interprofessional collaboration between dietary staff and nursing staff is efficient in increasing the accuracy of fluid balance charting. Results The nursing staff for the three data collection days were given pre- and postimplementation questionnaires on their perception of fluid balance charts before the intervention was implemented and after seeing the results (missed mL of fluids per patient) for the day after the intervention was implemented. A total of 11 nurses participated in the study questionnaires. Before and after the implementation, all 11 nurses stated that they rely heavily on fluid balance charts to make clinical decisions for their patients also citing that fluid balance charts are very important in the proper care of patients. All 11 of the nurses who participated checked off that doctors almost always, if not always, look at fluid balance charts when making clinical decisions for their patients. In the “Pre-Intervention Questionnaire however, 9 nurses checked that the accuracy of fluid balance charts as they are currently completed are mostly not accurate or were neutral on their perception on the accuracy of fluid balance charts. All 11 nurses checked the “Neutral” box or lower when asked about how often intake was recorded; 1 nurse checked “”Intake is Never Recorded,” 8 nurses checked “Intake is Mostly Not Recorded,” and 2 nurses checked that they were “Neutral” about the topic of intake recording. When asked about the effectiveness of the COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 16 fluid balance charts as they are completed now, 7 nurses checked that they are “Mostly not Effective” and 4 nurses checked that they are “Not Effective at All.” In the “Post-Intervention Questionnaire,” the nurses were shown the average milliliters that were missed on the intake and output charts for the patients and were asked to answer the same questions from the “Pre-Intervention Questionnaire” as if intake were recorded via nursing and dietary collaboration. The results showed that all 11 nurses believed that intake would be “Mostly Recorded” (n=8) or “Always Recorded” (n=3). The perception of accuracy of the fluid balance charts also increased with a majority (n=9) checking that fluid balance charts would be “Mostly Accurate” and two nurses checking that they would be “Very Accurate.” There was also an increase in the nursing confidence in their effectiveness in lineation with the accuracy of the fluid balance charts with The second portion of the study involved comparing the dietary calculation to the charted nursing staff estimation. A total of 22 patients were eligible for the study and of that number, data from 18 of the charts was used as four patients were discharged home on the day of data collection and only partial data was collected on them. After comparing the dietary calculation to the nursing estimation in the charts for day 1 of data collection, it was determined that the average difference between the two results for the 12-hour shift was 696.25 mL for the four patients that were observed. The total differences between the nursing estimation and the dietary calculation can be found in Figure 1a. Day 2 collection results showed that there was an average difference of 451.11 mL between the nursing estimation and the dietary calculation for the 9 patients included. Total differences between the nursing estimation and the dietary calculation can be found in Figure 1b. Day 3 of data collection included 5 patients and calculations showed an average difference of 766 mL incorrectly or COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 17 uncharted fluids. Total differences between the nursing estimation and the dietary calculation can be found in Figure 1c. Figure 1a: Nursing estimation of intake per tray versus dietary calculation on day 1 of data collection. Figure 1b: Nursing estimation of intake per tray versus dietary calculation on day 2 of data collection. Figure 1c: Nursing estimation of intake per tray versus dietary calculation on day 3 of data collection. After calculating the average differences of missed or inaccurately charted fluid amounts for each of the data collection days, results showed that the average difference in mL from all 18 patients was 637.79 mL. This data implies that over a typical length of stay at a hospital, about 4.8 days (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010), around three liters of fluids can go undocumented. Limitations Unfortunately, of the three days of data collection, only one day the primary researcher was able to utilize the dietary assistant. The first day, the dietary assistants did not distribute or collect patient trays leaving it to the principal researcher to act in lieu of the dietary assistant. The COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 18 second day of data collection applied the willing participation of the dietary assistant, Anthony Bughi. On the third day of data collection, the dietary assistant was approached about participation in the study, in which she stated it was out of her scope to participate. This may have skewed the results in a positive way as the researcher is previously well educated about the enhanced need for very close observation of patient intake and output. While each day of data collection did not proceed as expected, they provided crucial information about potential limitations as barriers that may face implementation of this type of intervention. Not all days will have a dietary assistant to collect the tray which could lead to another potential gap in care on these days. The tray collection would be left up to the nursing assistants and therefore the documentation would also have to fall to them as well. Another limitation that may arise with piloting this intervention is the unwillingness of dietary assistants to participate. The literature states that a “not-my-job” type of attitude may present a barrier to proper implementation and this was seen in this study as well. The dietary assistant stated that the calculation of intake and output is part of the nursing assistants’ job, not hers. Discussion There are many repercussions with missing an average of 637.79 mL per 12-hour shift in a fluid balance chart. Physicians often order continuous fluids for patients that are dehydrated or are at risk for dehydration. However, patients may also have comorbidities that may make unnecessarily running fluids dangerous such as heart failure or renal diseases. Intake and output is a necessary part of the nursing assessment and there is clearly a gap in care for patients when nursing staff is unable to accurately account for fluids that they consume. This proposed and piloted collaboration would take a step in closing the gap in this population’s care. COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 19 Another issue that presented itself in the results of the study was that of low nursing perceptions of the accuracy of fluid balance charts. If there is little to no confidence in their accuracy, the nursing staff may potentiate their incomplete perceive characteristic by not documenting intake and output that they witness. It is a vicious cycle that can be corrected with simple collaboration and communication. Nurses are known to be constantly busy and assisting in patient care, which makes interprofessional communication difficult, however, many healthcare institutions are creating tools to help keep the patient connected with their health care providers. At the Penn State Hershey Medical Center, there are patient information whiteboards bedside already in use for every patient bed on the floor and are updated at least every change of shift. The information includes the patient’s preferred name, who their physician is, the nurse for the shift, and what diet they are currently on. With this tool already in place, it would be simple to equip the dietary assistants with a dry erase marker to utilize along with the white boards. This would cut tackle the overwhelming issue of trying to create multiple points of communication between every nurse on the floor and the dietary assistant. In addition, more communication with the dietary office administrators may have resulted in better, more cooperative participation of the dietary assistants. Not only would this help to better guide clinical decisions, it could potentially save the hospital in expenses that they could incur from complications that may have been prevented if accurate intake and output were documented in the fluid balance charts. Much time and effort is spent on the prevention of falls, hospital associated pneumonia, and hospital acquired urinary tract infections as these are major points of lost money for the hospitals. Continued research into better utilization of staff and more accurate documentation of intake and output could potentially COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 20 save hospital institutions as they may help to identify and prevent complications of fluid overload or dehydration in patients. Summary Overall, this study aimed to highlight the often overlooked gap in care: missed intake from meal trays. The existing literature shows that little research has been done on the topic, only citing that is may be a missed component of patient care. While there have been some studies that looked into replacing the fluid balance charts altogether in favor of daily weights, no studies have demonstrated success in revealing that fluid balance charts are no longer needed. Therefore, it is necessary not to find alternative methods to replace them, but to adapt the way they are charted to obtain the most accurate values. The accurate values of intake and output in fluid balance charts help to guide physicians and nursing staff to care and make the best clinical decisions for patients. With inaccuracies found in these charts, clinical judgment is skewed and could possibly result in poor patient outcomes. The results of this study support that nursing perceptions of the accuracy and effectiveness of fluid balance charting as it is currently completed are low. The comparison of the nursing estimations to dietary calculations demonstrate that there is a dire need to address this issue of inaccurate intake and output documentation. On average, over half of a liter of fluids goes undocumented on a given 12-hour shift on the floor. This missed assessment demonstrates a need for further research into the issue. While many issues arose throughout the course of this study, small changes to implementation could potentially overcome the hurdles. Simple COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION adjustments in the utilization of pre-existing tools such as bedside whiteboards could help facilitate smoother interprofessional collaboration. 21 COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 22 References Alexander, L., & Allen, D. (2011). Establishing an evidence-based inpatient medical oncology fluid balance measurement policy. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 15(1), 23–25. http://doi.org/10.1188/11.CJON.23-25 Armstrong-Esther, C. A., Browne, K. D., Armstrong-Esther, D. C., & Sander, L. (1996). The institutionalized elderly: Dry to the bone! International Journal of Nursing Studies, 33(6), 619–628. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7489(96)00023-5 Baldini, G., Bagry, H., Aprikian, A., & Carli, F. (2009). Postoperative urinary retention. Anethesiology, 10(5), 1139–1157. Bekhof, J., Van Asperen, Y., & Brand, P. L. P. (2013). Usefulness of the fluid balance: A randomised controlled trial in neonates. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 49, 486– 492. http://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.12214 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2010). Number, rate, and average length of stay for discharges from short-stay hospitals, by age, region, and sex. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhds/1general/2010gen1_agesexalos.pdf Chung, L. H., Chong, S., & French, P. (2002). The efficiency of fluid balance charting: An evidence-based management project. Journal of Nursing Management, 10, 103–113. http://doi.org/10.1046/j.0966-0429.2001.00296.x Colley, W. (2015). Use of frequency volume charts and voiding diaries. Nursing Times, 111(5), 12–16. COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 23 Eastwood, G. M. (2006). Evaluating the reliability of recorded fluid balance to approximate body weight change in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Heart & Lung: The Journal of Acute and Critical Care, 35(1), 27–33. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2005.06.001 Galen, B. (2015). Underpad weight to estimate urine output in adult patients with urinary incontinence. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology, 12(2), 189-190. doi:10.11909/j.issn.16715411.2015.02.016 Holte, K., Sharrock, N., & Kehlet, H. (2002). Pathophysiology and clinical implications of perioperative fluid excess. British Journal of Anesthesia, 89(4), 622–632. Kalisch, B. J. (2006). Missed nursing care: A qualitative study. Journal of Nursing Care Quality Vol. 21, No. 4, Pp. 306-313, 21(4), 306–313. McGloin, S. (2015). The ins and outs of fluid balance in the acutely ill patient. British Journal of Nursing, 24(1), 14–19. Meiner, S. E. (2002). Fluid balance documentation: A case study of daily weight and intake/output omissions. Geriatric Nursing, 23(1), 46-47. Reid, J., Robb, E., Stone, D., Bowen, P., Baker, R., Irving, S., & Waller, M. (2004). Improving the monitoring and assessment of fluid balance. Nursing Times, 100(20), 36–39. Scales, K., & Pilsworth, J. (2008). The importance of fluid balance in clinical practice. Nursing Standard, 23(47), 50–57. COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 24 Schneider, A. G., Baldwin, I., Freitag, E., Glassford, N., & Bellomo, R. (2012). Estimation of fluid status changes in critically ill patients: Fluid balance chart or electronic bed weight? Journal of Critical Care, 27(6), 745.e7–745.e12. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2011.12.017 Wakeling, J. (2011). Improving the hydration of hospital patients. Nursing Times, 107(39), 21– 23. Wise, L. C., Mersch, J., Racioppi, J., Crosier, J., & Thompson, C. (2000). Evaluating the reliability and utility of cumulative intake and output. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 14(3), 37–42. Zwarenstein, M., & Reeves, S. (2006). Knowledge translation and interprofessional collaboration: Where the rubber of evidence-based care hits the road of teamwork. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 46–54. http://doi.org/10.1002/chp.50 COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 25 Appendix A Thank you for your participation in this brief study. The aim of this study is two-fold: 1. To measure the perceptions of fluid balance charting (I&O) of the nursing staff. 2. To measure the effectiveness of collaboration between dietary staff and nursing staff on I&O charting accuracy. The first aim will be investigated via a pre- and post-intervention questionnaire. The second will be done by asking dietary assistants that collect trays at the end of meals to record the fluid intake of the patient and report them to me (Elise Howard S.N.). These values will then be compared to those estimated by the nursing staff. These results will only be used to study the effectiveness that this collaboration has on the accuracy of intake and output charts. The results will be shared with the Second Degree Accelerated Nursing 2015/16 cohort and associated professors. Names of participants can remain anonymous if requested. Names will only indicate participation in this study. When the results of the study are presented, values will not be associated with any particular individual. Thank you! Elise Howard, S.N. B.S. Biobehavioral Health College of Nursing The Pennsylvania State University COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 26 Appendix B Pre-Intervention Questionnaire Instructions: Please rate your perception of the following areas on a scale of 1 to 5. For each category, the place a checkmark in the box that corresponds with how you feel. * Note that “FBC” stands for “fluid balance charts,” also known as “intake and output” documentation. 1 2 3 4 5 Not Important At All Mostly Not Important Neutral Mostly Important Very Important Not At All Mostly Do Not Help Neutral Mostly Help All The Time Not Effective At All Mostly Not Effective Neutral Mostly Effective Very Effective Not Accurate At All Mostly Not Accurate Neutral Mostly Accurate Very Accurate Doctors Never Look Doctors Mostly Do Not Look Neutral Doctors Mostly Look Doctors Always Look Output is Never Recorded Output is Mostly Not Recorded Neutral Output is Mostly Recorded Output is Always Recorded Intake is Never Recorded Intake is Mostly Not Recorded Neutral Intake is Mostly Recorded Intake is Always Recorded IMPORTANCE OF FBCS FBCS HELP ME M AKE CLINICAL DECISIONS EFFECTIVENESS OF FBCS ACCURACY OF FBCS DOCTORS LOOK AT FBCS OUTPUT RECORDED INTAKE RECORDED COLLABORATION OF INTAKE AND OUTPUT DOCUMENTATION 27 Post-Intervention Questionnaire Instructions: Please rate your perception of the following areas on a scale of 1 to 5. For each category, the place a checkmark in the box that corresponds with how you feel. * Note that “FBC” stands for “fluid balance charts,” also known as “intake and output” documentation. 1 2 3 4 5 Not Important At All Mostly Not Important Neutral Mostly Important Very Important Not At All Mostly Do Not Help Neutral Mostly Help All The Time Not Effective At All Mostly Not Effective Neutral Mostly Effective Very Effective Not Accurate At All Mostly Not Accurate Neutral Mostly Accurate Very Accurate Doctors Never Look Doctors Mostly Do Not Look Neutral Doctors Mostly Look Doctors Always Look Output is Never Recorded Output is Mostly Not Recorded Neutral Output is Mostly Recorded Output is Always Recorded Intake is Never Recorded Intake is Mostly Not Recorded Neutral Intake is Mostly Recorded Intake is Always Recorded IMPORTANCE OF FBCS FBCS HELP ME M AKE CLINICAL DECISIONS EFFECTIVENESS OF FBCS ACCURACY OF FBCS DOCTORS LOOK AT FBCS OUTPUT RECORDED INTAKE RECORDED