9116cc365599636

advertisement

1

Lecture one

Traditional definitions of linguistics: typical subfields of linguistics

The present lecture tackles the following points:

- Traditional definitions of linguistics.

- Recognizing and revising such definitions.

- An overview of typical subfields of linguistics.

- Approaches to language studies/linguistics: synchronic, diachronic, etc.

- Introducing modern linguistics with its up-to-date interdisciplinary fields.

Sources/References

- Meyer, Charles F. (2009). Introducing English Linguistics.

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook

What is Linguistics?

Linguistics is often (but not usually) defined as 'the scientific study of language or of

particular languages' (Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary). Bauer (2007) likewise states

that 'a typical dictionary definition of linguistics is something like ‘the science of language’.

However he (ibid) believes that such a definition is not always helpful, for a number of

reasons:

• Such a definition does not make clear in what respects linguistics is

scientific, or what is meant by science in this context.

• Such a definition masks the fact that it is, for some linguists, controversial to term their

subject a science.

• Such a definition fails to distinguish linguistics from related fields such as philology.

• The word ‘science’ may carry with it some misleading connotations.

A rather looser definition, such as ‘linguistics is the study of all the phenomena involved

with language: its structure, its use and the implications of these’, might be more helpful,

even if it seems vaguer.

It is thus important to note that although there is no one and the same definition of the term

'linguistics', it generally studies, tackles and investigates different aspects of human

language in a systematic and scientific manner.

2

What does linguistics cover ?

Linguistics deals with human language. This includes deaf sign-languages, but usually

excludes what is often termed BODY-LANGUAGE (a term which itself covers a number of

different aspects of the conscious and unconscious ways in which physiological actions and

reactions display emotions and attitudes).

Human language is just one way in which people communicate with each other, or gather

information about the world around them. The wider study of informative signs is called

SEMIOTICS, and many linguists have made contributions to this wider field.

3

One obvious way of studying language is to consider what its elements are, how they are

combined to make larger bits, and how these bits help us to convey messages. The first part

of this, discovering what the elements are, is sometimes rather dismissively termed

TAXONOMIC or classificatory linguistics. But given how much argument there is about

what the categories involved in linguistic description are, this is clearly an important part of

linguistics, and is certainly a prerequisite for any deeper study of language.

The study of the elements of language and their function is usually split up into a number of

different subfields.

1. PHONETICS deals with the sounds of spoken language: how they are made, how they

are classified, how they are combined with each other and how they interact with each other

when they are combined, how they are perceived. It is sometimes suggested that phonetics

is not really a part of linguistics proper, but a sub-part of physics, physiology, psychology

or engineering (as in attempts to mimic human speech using computers). Accordingly, the

label LINGUISTIC PHONETICS is sometimes used to specify that part of phonetics which

is directly relevant to the study of human language.

2. PHONOLOGY also deals with speech sounds, but at a rather more abstract level. While

phonetics deals with individual speech sounds, phonology deals with the systems which

incorporate the sounds. It also considers the structures the sounds can enter into (for

example, syllables and intonational phrases), and the generalisations that can be made about

sound structures in individual languages or across languages.

4

3. MORPHOLOGY deals with the internal structure of words – not with their structure in

terms of the sounds that make them up, but their structure where form and meaning seem

inextricably entwined. So the word cover is morphologically simple, and its only structure

is phonological, while lover contains the smaller element love and some extra meaning

which is related to the final <r> in the spelling. Another way of talking about this is to say

that morphology deals with words and their meaningful parts.

4. SYNTAX is currently often seen as the core of any language, although such a prioritising

of syntax is relatively new. Syntax is concerned with the ways in which words can be

organised into sentences and the ways in which sentences are understood. Why do

apparently parallel sentences such as Pat is easy to please and Pat is eager to please have

such different interpretations (think about who gets pleased in each case)?

5. SEMANTICS deals with the meaning of language. This is divided into two parts,

LEXICAL SEMANTICS, which is concerned with the relationships between words, and

SENTENCE SEMANTICS, which is concerned with the way in which the meanings of

sentences can be built up from the meanings of their constituent words. Sentence semantics

often makes use of the tools and notions developed by philosophers; for example, logical

notation and notions of implication and denotation.

5

6. PRAGMANTICS deals with the way the meaning of an utterance may be influenced by

its speakers or hearers interpret it in context. For example, if someone asked you Could you

close the window?, you would be thought to be uncooperative if you simply answered Yes.

Yet if someone asked When you first went to France, could you speak French? Yes would

be considered a perfectly helpful response, but doing something like talking back to them in

French would not be considered useful. Pragmatics also deals with matters such as what the

difference is between a set of isolated sentences and a text, how a word like this is

interpreted in context, and how a conversation is managed so that the participants feel

comfortable with the interaction.

7. LEXICOLOGY deals with the established words of a language and the fixed

expressions whose meanings cannot be derived from their components: idioms, clichés,

proverbs, etc. Lexicology is sometimes dealt with as part of semantics, since in both cases

word-like objects are studied.

In principle, any one of these levels of linguistic analysis can be studied in a number of

different ways.

• They can be studied as facets of a particular language, or they can be studied across

languages, looking for generalisations which apply ideally to all languages, but more often

to a large section of languages. The latter type of study is usually called the study of

LANGAUGE UNIVERSALS, or LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY if the focus is on particular

patterns of recurrence of features across languages.

They can be studied as they exist at some particular time in history (e.g. the study of the

morphology of fifteenth-century French, the

study of the syntax of American English in 2006, the phonetics of the languages of the

Indian subcontinent in the eighteenth century) or they can be studied looking at the way the

patterns change and develop over time. The first approach is called the SYNCHRONIC

approach, the second the DIACHRONIC or historical approach.

They can be studied with the aim of giving a description of the system of a particular

language or set of languages, or they can be studied with the aim of developing a theory of

how languages are most efficiently described or how languages are produced by speakers.

The first of these approaches is usually called DESCRIPTIVE LINGUISTICS, the second

is often called THEORITICAL LINGUISTICS.

6

They can be treated as isolated systems, although all speakers talk in the same way as each

other at all times, or they can be treated as systems with built-in variability, variability

which can be exploited by the language user to mark in-group versus out-group, or to show

power relations, or to show things as diverse as different styles and personality traits of the

speaker. The latter types are dealt with as part of SOCIOLINGUISTICS, including matters

such as DIALECTOLOGY.

We can study these topics as they are in the adult human, or we can study the way they

develop in children, in which case we will study LANGUAGE ACQUISITION. Perhaps

more generally, we can view the development of any of these in the individual human, that

is we can take the ONTOGENETIC point of view, or we can consider the way each has

developed for the species, taking the PHYLOGENETIC point of view.

Finally, most of these facets of linguistics can be studied as formal

systems (how elements of different classes interact with each other, and how the system

must be arranged to provide the outputs that we find in everyday language use).

Alternatively, they can be studied in terms of how the use to which language is put in

communication and the cognitive functions of the human mind shape the way in which

language works (iconicity, the notion that language form follows from meaning to a certain

extent, is thus a relevant principle in such studies). This is the difference between FORMAL

and FUNCTIONAL approaches to language.

In principle, Bauer (2007) argues, each of these choices is independent, giving a huge range

of possible approaches to the subject matter of linguistics.

Many people are less interested in the precise workings of, say, phonology than they are in

solving problems which language produces for humans. This study of language problems

can be called APPLIED LINGUISTICS though a word of warning about this label is

required. Although there are people who use the term applied linguistics this broadly, for

others it almost exclusively means dealing with the problems of language learning and

teaching. Language learning (as opposed to language acquisition by infants) and teaching is

clearly something which intimately involves language, but often it seems to deal with

matters of educational psychology and pedagogical practice which are independent of the

particular skill being taught. Other applications of linguistics may seem more centrally

relevant. These include:

(NB: the following will be detailed and be the subject matter of the next lecture).

What does linguistics cover ?

- ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

- FORENSIC LINGUISTICS

- LANGUAGE POLICY

- LEXICOGRAPHY

- MACHINE TRANSLATION

- SPEECH AND LANGUAGE THERAPY (CLINICAL LINGUISTICS included)

- SPEECH RECOGNITION (VOICE RECOGNITION included)

7

- SPEECH ANALYSIS

- TEACHING

Other subfields of linguistics include the following:

- AREAL LINGUISTICS

- COMPARATIVE LINGUISTICS

- COMPUTATIONAL LINGUISTICS (CORPUS LINGUISTICS included)

- EDUCATIONAL LINGUISTICS

- ETHNOLINGUISTICS (ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS included)

- MATHEMATICAL LINGUISTICS

- SOCIOLINGUISTICS

- PSYCHOLINGUISTICS

NEUROLINGUISTICS

8

Lecture two

Modern linguistics with its up-to-date applications and subfields

The present lecture tackles the following points:

- Modern linguistics with its up-to-date applications and subfields (a continuation of the

previous lecture).

- Understanding the relationships between such applications and subfields and language use

in real life.

- Modern terms used in today's linguistics (scattered throughout the lecture).

Sources/References

- Meyer, Charles F. (2009). Introducing English Linguistics.

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook.

Introduction

Throughout the previous lecture and so far, we have come to recognize the denominations

(names/classifications) of modern linguistic applications as well as up-to-date subfields of

modern linguistics. To illustrate this couple of points, Bauer (2007) states that "Other

applications of linguistics may seem more centrally relevant. These include:

Artificial Intelligence

Turing (1950) suggested that a machine should be termed intelligent when humans could

interact with it without realising they were not interacting with another human. Among

many other problems, this involves the machine being able to produce something akin to

human language.

9

Forensic Linguistics

This deals with the use of language in legal contexts, including matters such as the

linguistic techniques of cross examination, the identification of speakers from taperecordings, and the identification of authorship of disputed documents.

Language Policy

Some large organisations and nations have language policies to provide guidelines on how

to deal with multilingualism within the organisation.

Lexicography

The creation of dictionaries; although some people claim that this is not specifically to do

with linguistics, it is a linguistic study in that it creates vocabulary lists for individual

languages, including lists of things like idioms, and in translating dictionaries provides

equivalents in another language.

10

Machine Translation

The use of computers to translate a written text from one language to another.

Speech and Language therapy

Speech and language therapists deal with people who, for some reason, have not acquired

their first language in such a way that they can speak it clearly, or with the re-education of

speakers who have lost language skills, e.g. as the result of a stroke. The linguistic aspects

of this are sometimes called CLINICAL LINGUISTICS.

Speech Recognition

The use of computers to decode spoken language in some way; this may include computers

which can write texts from dictation, phone systems which can make airline bookings for

you without the presence of any human, or computers which can accept commands in the

form of human language. More specifically, VOICE RECOGNITION can be used for

security purposes so that only recognised individuals can access particular areas.

11

Speech Analysis

The use of computers to produce sound waves which can be interpreted as speech.

Teaching

It is clear that second- and foreign-language teaching

involve, among other things, linguistic skills, but so does much mother-language teaching,

including imparting the ability to read and to write. At more advanced levels, teaching

students to write clearly and effectively may involve some linguistic analysis.

Another way of looking at what linguistics covers is by taking the list of topics given at the

head of this section as being some kind of core, and then thinking of all the types of

‘hyphenated’ linguistics that are found.

Areal Linguistics

Deals with the features of linguistic structure that tend to characterise a particular

geographical area, such as the use of retroflex consonants in unrelated languages of the

Indian subcontinent.

12

Comparative linguistics

Deals with the reconstruction of earlier stages of a language by comparing the languages

which have derived from that earlier stage.

Computational Linguistics

Deals with the replication of linguistic behaviour by computers, and the use of computers in

the analysis of linguistic behaviour. This may include CORPUS LINGUISTICS the use of

large bodies of representative text as a tool for language description.

Educational Linguistics

Investigates how children deal with the language required to cope with the educational

system.

13

Ethonlinguistics

Deals with the study of language in its cultural context. It can also be called

ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS.

Mathematical Linguistics

Deals with the mathematical properties of languages or the grammars used to describe those

languages.

14

Neurolinguistics

Deals with the way in which linguistic structures and processes are dealt with in the brain.

Psycholinguistics

Deals with the way in which the mind deals with language, including matters such as how

language is stored in the mind, how language is understood and produced in real time, how

children acquire their first language, and so on.

Sociolinguistics

Deals with the way in which societies exploit the linguistic choices open to them, and the

ways in which language reflects social factors, including social context.

15

Conclusion

We can finish by pointing out that the history of linguistic thought is itself a fascinating area

of study, since ideas about language are closely related to the philosophical fashions at

different periods of history, and often reflect other things that were occurring in society at

the time.

Although we have so far discussed a big number of linguistic applications and subfields,

Bauer (2007), as an instance, states that Even this overview is not complete. It indicates,

though, just how broad a subject linguistics is.

16

Lecture three

Linguistic applications and subfields and language use in real life

The present lecture tackles the following points:

- Chomsky's influence on linguistics/grammar.

- Competence and performance.

- Transformational-generative grammar.

Grammaticality and acceptability.

Sources/References

- Kasher, Asa (ed.) (1991). The Chomskyan Turn. Cambridge MA and Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook ---------------- (2001).

Morphological Productivity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Meyer, Charles F. (2009). Introducing English Linguistics.

Chomsky's influence

Noam Chomsky is the world’s most influential linguist. His influence can be seen in many

ways, from the expansion of linguistics as an academic subject in the wake of his early

work on the nature of grammars to the way in which even linguists who do not agree with

him define their position in relation to his. His ideas have attracted many brilliant people to

take up linguistics and contribute to the study of language. It has become common to talk of

a ‘Chomskyan revolution’ in linguistics beginning in the late 1950s or early 1960s as the

influence of his teaching permeated the way in which language was viewed and was

discussed. If the term ‘revolution’ may be a little over-dramatic, linguistics certainly took

what Kasher (1991: viii) calls a ‘Chomskyan Turn’ at that point.

17

Competence and performance

Chomsky also distinguishes between the speakers’ actual knowledge of the language, which

is termed COMPETENCEE, and the use of that knowledge, which is termed

PERFORMANCE… Any piece of text (spoken or written) represents a performance of

language, which will match the speaker’s competence more or less inaccurately. Thus

performance is often taken as a poor guide to competence, but competence is the object of

study for the linguist.

As with so many of the claims Chomsky makes, this one has been the subject of criticism,

some focusing on the structured nature of variation within performance and the

correspondingly variable nature of competence, some focusing on the performance as a

body of evidence whose close analysis can lead to a more sophisticated appreciation of how

the speaker-listener’s competence might be structured (the first of these criticisms comes

from sociolinguists, the second from corpus linguists and psycholinguists). It also seems

that it can be difficult to tell whether a particular phenomenon is best seen as a matter of

competence or a matter of performance, despite the apparently clear-cut division between

the two (see e.g. Bauer 2001: 29-32).

Generativism and transformationalism

Chomskyan grammar in the early days was regularly termed ‘generative transformational’,

and while the label is less used today, the principles remain unchanged.

The term ‘generate’ in generative is to be understood in a mathematical sense, whereby the

number one and the notion of addition can be used to generate the set of integers or where

2n can be used to generate the sequence 2, 4, 8, 16…. In linguistics a generative grammar is

one which contains a series of rules… which simultaneously (a) confirm (or otherwise) that

a particular string of elements belongs to the set of strings compatible with the grammar and

(b) provide at least one grammatical description of the string (if there is more than one

description, the string is ambiguous) (see Lyons 1968: 156).

18

The first thing to notice about this is that a generative grammar is a FORMAL grammar. It

is explicit about what is compatible with it. This is in direct contrast to most pedagogical

grammars, which leave a great deal of what is and is not possible up to the intuition of the

learner. In practice, this often leads to disputes about how much the grammar is expected to

account for. To use a famous example of Chomsky’s (1957: 15), is 'Colourless green ideas

sleep furiously'.

to be accepted as a sentence generated by the grammar, on a par with 'Fearless red foxes

attack furiously' (and, significantly, different from Furiously sleep ideas green colourless,

which the grammar should not generate)? If so, its oddness must be due to some semantic

or pragmatic compatibility problems which are not part of the syntax. Alternatively, should

the grammar specify that sleep is not compatible with furiously and that abstract nouns

cannot be modified by colour adjectives (although, having said that, I have seen the

expression green ideas in use, where green meant ‘ecologically sound’)? In 1957 Chomsky

was clear that the grammar would and should generate this sentence, despite its superficial

oddity. McCawley (1971: 219) supports this view, claiming that ‘A

person who utters [My toothbrush is alive and is trying to kill me] should be referred to a

psychiatric clinic, not to a remedial English course.’ Despite such problems, the explicitness

of Chomskyan grammar is one of its great strengths. It has led to computational approaches

to linguistics in which (partial) grammars are tested by implementing them on computer,

and such approaches have implications for the eventual use of natural languages by

computer systems.

19

The second thing to notice is that although the rules in linguistics are usually stated as

operations which look as though they are instructions to produce a particular string, in

principle they are neutral between the speaker and the listener, merely stating that the string

in question does or does not have a coherent parse.

Grammaticality and acceptability

In principle, something is GRAMMATICAL if it is generated by the grammar, and

ungrammatical if it is not. Since we do not have complete generative grammars of English

(or any other language) easily available, this is generally interpreted as meaning that a

string is grammatical if some linguist believes it should be generated by the grammar, and

ungrammatical otherwise. Given what was said above, it should be clear that there is a

distinction to be drawn between strings which are grammatical and those which are

ACCEPTABLE, that is, judged by native speakers to be part of their language. 'Colourless

green ideas sleep furiously' is possibly grammatical, but may not be acceptable in English

(though poems have been written using the string). There’s lots of people here today is

certainly acceptable, but it might not be grammatical if the grammar in question requires the

verb to agree with the lots (compare Lots of people are/*is here today). Although the

asterisk is conventionally used to mark ungrammatical sequences (this generalises on its

meaning in historical linguistics, where it indicates ‘unattested’), it is sometimes used to

mark unacceptable ones.

20

Lecture four

Language, Semantic, Phonological, Syntactic and Absolute universals

The present lecture tackles the following points:

- Language universals.

- Semantic universals.

- Phonological universals.

- Syntactic universals.

- Absolute universals – universal tendencies; implicational – non implicational universals.

Sources/References

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook.

- Ipsen, Guido (1999). The Interactive MultiMedia Linguistics for Beginners Textbook.

Language universals

Nearly five thousand languages are spoken in the world today. They seem to be quite

different, but still, many of them show similar principles, such as word order. For example,

in languages such as English, French, and Indian, the words of the clause take the order of

first the subject, then the verb, and then the direct object.

There even exist basic patterns or principles that are shared by all languages. These patterns

are called universals.

When the same principles are shared by several languages, we speak of language types.

There are several examples for universals.

21

Semantic universals

There are semantic categories that are shared by all cultures and referred to by all

languages- these are called semantic universals. There are many examples of semantic

universals. Let's discuss two of them:

One semantic universal regards our notion of color. There exist eleven basic color terms:

black, white, red, green, blue, yellow, brown, purple, pink, orange, and gray. The pattern

that all languages universally abide by, is that they do not entertain a notion of a color term

outside of that range. This means, any imaginable color is conceived of as a mixture, shade,

or subcategory of one of these eleven basic color terms. As a result, one way of classifying

languages is by color terms. The eleven color terms are not in usage equally among the

languages on Earth. Not all languages have all basic color terms. Some have two, some

three, and some four. Others have five, six, or seven, and some have eight to eleven. Those

with two color terms always have black and white, those with three black, white, and red,

and those with more have additional basic color terms according to the order in the list

given above. This is a universal pattern. The languages which have the same basic color

terms in common belong to the same language type. Hence, we find seven classes of

languages according to this scheme.

Semantic universals

Another semantic universal is the case of pronouns. Think of what it is you do when you

talk to someone about yourself. There is always the "I", representing you as the speaker,

and the "you", meaning the addressee. You could not possibly do without that, and neither

could a speaker of any other language on earth. Again, we find a universal pattern here.

Whenever you do not talk about yourself as a person, but as a member of a group, you use

the plural "we". English is restricted to these two classes of pronouns: singular and plural,

each in the first, second, and third person. All languages that evince this structure are

grouped into one language type. There are other languages that make use of even more

pronouns. In some languages, it is possible to address two people with a pronoun, that

specifically indicates, not just their being plural, but also their being 'two' people; this is

then the dual pronoun.

22

Other examples are languages that have pronouns to refer to the speaker and the addressee

together, called inclusive pronouns. Exclusive pronouns refer to the speaker together with

people other than the addressee. However, these are not among the European languages.

Phonological universals

Different languages may have very different sets of vowels. If you are familiar with a few

foreign languages, you may find it difficult to believe there are universal rules governing

the distribution of vowels, but they do exist. Remember our example of basic color terms: A

similar pattern could be drawn on the basis of the vowel system. Languages with few

vowels always have the same set of vowel types. And if a language has more vowels, it is

always the same type of vowel that is added to the set. These vowels may not always sound

exactly the same, but they are always created at the same location in our vocal apparatus.

Syntactic universals

Remember the word order of English I mentioned above. Hmhm, you say: that cannot be a

universal rule, since you know other sentences from English and possibly from other

languages which do not follow this order. You are right, but the order subject, verb, object

(SVO) may be defined as the basic order of English sentences. In other languages there are

different "basic" orders, such as Japanese (SOV) or Tongan (VSO), a Polynesian language.

After an extensive study, one can define two different sets of basic orders that languages

follow: First SVO, VSO, SOV and second VOS, OVS, OSV. What is the difference? In the

first set the subject precedes the object, in the second set it follows the object. Since the first

set is the one which applies to the basic structures of far more languages than the second

one does, the universal rule is that there is an overwhelming tendency for the subject of a

sentence to precede the direct object among the languages of the world.

23

Absolute universals

Universal tendencies; implicational – nonimplicational universals.

Of course, not all universals can be found in all languages. With so many tongues spoken, it

would be hard not to find any exceptions. Most languages have not even been the .subject

of extensive research as of yet. However, some rules appear without exception in the

languages which have been studied so far. We call these absolute universals. If there are

minor exceptions to the rule, we speak of universal tendencies or relative universals. In

saying this, we take for granted that exceptions may be found in future surveys among

languages which have remained unexplored up to the present day.

Sometimes a universal holds only if a particular condition of the language structure is

fulfilled. These universals are called implicational. Universals which can be stated without a

condition are called non implicational. In other words, whenever a rule "If ... then ..." is

valid, the universal appears in the structure of the respective language.

There are thus four types of universals: implicational absolute universals, implicational

relative universals, nonimplicational absolute universals, and non implicational relative

universals. The final determination of which type a universal belongs to is dependent on

intensive field research.

24

Lecture five

Language acquisition and disorders

The present lecture tackles the following points:

- Language acquisition and disorders.

- Child language acquisition.

- Language development and maturation.

Sources/References

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook.

- Ipsen, Guido (1999). The Interactive MultiMedia Linguistics for Beginners Textbook.

Introduction

The need for understanding the way a person acquires his or her language (including

whether first/native languages or second/foreign languages) in addition to the mental

processes thereby people proceed to grasp and perceive language is one of the main

concerns of the LANGUAGE ACQUISITION activity. Below you are introduced to main

ideas of language acquisition (Ipsen: 1999).

Language acquisition and disorders

A part from the general historical development of languages, there is another, rather

personal development in each of us when we acquire a language. We undergo child

language acquisition, development, and maturation. We acquire second, third, fourth or

even more languages in school or when we travel abroad. Another feature of personal

linguistic developments are language disorders due to malfunctions of certain areas of the

brain…. (to be developed in the following lectures)

N.B.: Refer to lecture 2 because what is mentioned above has to do with some of the

findings of Neurolinguistics. This branch of linguistics investigates the relationship between

the brain and language.

Child language acquisition

Children have to learn language from scratch, although the capability to speak is inherent in

everyone. There are certain milestones and stages of language acquisition during the child's

first months and years.

25

MILESTONES

I: 0–8 weeks. Children of this age are only capable of reflexive crying. We also call this the

production of vegetative sounds.

II: 8–20 weeks. Cooing and laughter appears in the child's vocal expression. III: 20–30

weeks. The child begins with vocal play. This includes playing with vowels (V) and

consonants (C), for example: "AAAOOOOOUUUUIIII".

IV: 25–50 weeks. The child begins to babble. There are two kinds of babbling, a)

reduplicative babbling CVCV, e.g., "baba", and b) variegated babbling, e.g., VCV "adu".

V: 9–18 months. The child starts to produce melodic utterances. This means that stress and

intonation are added to the sound chains uttered.

After having passed these milestones, children are, in essence, capable of pronouncing

words of the natural language.

STAGES

From this time on, children start to produce entire words. There are three stages, each

designating an increasing capability to use words for communicative purposes:

I: Single words and holophrases. Children may use a word to indicate things or persons,

e.g., "boo" (=book), or "mama". Also, a single word is employed to refer to entire contexts.

At this stage, "shoe" could mean "Mama has a nice shoe", "Give me my shoe" or even "I

want to wear my new red shoes when we go for a walk"!

26

II: The next stage is the usage of two word phrases. This stage is also called telegraphic

speech. It begins around the second birthday, maybe sooner or later, depending on the child.

Examples are "Dada gone", "cut it", "in car", "here pear". At this stage, children design socalled pivot grammars. This means that the child has a preference for certain words as the

pivotal (axis) words, implementing a variety of other words at different points in time to

create phrases.

III: The child begins to form longer utterances. These lack grammatical correctness at first

and are perceived as, though meaningful, rather rough assemblies of utterances. Examples

are "dirty hand wash it", "glasses on nose", "Daddy car coming", or even "car sleeping bed",

which a boy uttered, meaning that the car was now parked in the garage.

There are many phonological and grammatical features of speech development, all of which

cannot be listed here. A characteristic of children's early language is the omission of

consonants at the beginning, ending, or in consonant clusters in words. Examples: "boo"

instead of "book", "at" instead of "cat", or "ticker" instead of "sticker". Children learn

grammatical morphemes, commonly referred to as "endings", in a certain order. They often

start with the present progressive "-ing", as in "Mama talking". More complex forms, such

as the contractible auxiliary be (as in "Pat's going") are learned at a later point in time.

Language development and maturation

Parents from different cultures behave differently towards their children as far as linguistic

education is concerned. In some areas of the world, people think that baby talk, or

Motherese hems linguistic development. There are also cultures where parents talk to their

children as they would to adults), or where they do not put so much thought into how to

teach their children language at all. When taking a closer look, no particular advantages or

disadvantages can be found.

Children's language is creative, but rule-governed. These rules comprise the seven operating

principles of children's language. These principles correspond to the essential

communicative needs of a child. One main aspect in all principles is the predominant use of

the active voice, the passive voice requiring a more complex understanding of concepts.

• The instrumental principle serves to indicate the personal needs of the child. These are the

"I want" phrases.

• The regulatory principle helps to demand action of somebody else: "Do that."

• "Hello" is the utterance - among others - which represents the interactional principle. It is

very important for establishing contact.

• The personal principle carries the expressive function. "Here I come" is a proper

substitution for many phrases.

• The heuristic "Tell me why"-principle is very important because once the child is able to

form questions, language helps in the general learning process.

27

• The imaginative principle comes in when the child wants to impart his or her dreams or

fantasies. It is also what applies when the child pretends

Information is also important for children's communication. To tell others about the own

experience soon becomes important.

Another major step in language development is taken when the child learns how to write.

Again, there are several stages:

I: Preparatory. Age approx. 4–6 years.

The child acquires the necessary motorical skills. Also, the principles of spelling are

learned.

II: Consolidation. Age approx. 7 years

When the child begins to write, its writing reflects its spoken language. This does not only

refer to the transcription of phonetic characteristics, but also to word order and sentence

structure.

III: Differentiation. Age approx. 9 years

Writing now begins to diverge from spoken language; it becomes experimental. This means

that the writing of the child does not have to reflect speech. The child learns to use writing

freely and sets out to experiment with it.

IV: Integration. Age approx. mid-teens

Around this age, children/teens develop their own style. A personal voice appears in the

written language and the ability to apply writing to various purposes is acquired.

28

Lecture six

Second language acquisition

The present lecture tackles the following points:

- Second language acquisition.

- New terminology: Source Language 'SL' ,Target Language 'TL', Language 2 'L2' etc.

- Features of 'interlanguage'/interlanguage stage

. Sources/References

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook.

- Ipsen, Guido (1999). The Interactive MultiMedia Linguistics for Beginners Textbook.

Second language acquisition

Some aspects of second language acquisition are similar to first language acquisition. The

learner has already acquired learning techniques and can reflect on how to learn best.

However, learning languages depends on the personality, age, intelligence, and active

learning strategies of the learner.

The learners of a second language (L2) start out with their own language, which we call

source language. They are on their way to learn a target language (TL). All that lies inbetween we call interlanguage. All L2 speakers are on some stage of interlanguage.

Beginners are closer to their source language (SL), experts of L2 are closer to the target

language. And if we don’t continue with our studies, our interlanguage competence may

even decrease. People who have lived in foreign countries for a long time are often so close

to the target language that they hardly differ from native speakers. There are some features

of interlanguage which are worthwhile to look at. They play an important role in the

learning process. Everybody experiences their effects in language learning.

Fossilization

At a certain stage the learner ceases to learn new aspects of the TL. Although perhaps

capable to express himself/herself in a grammatically correct way, the learner here does not

proceed to explore the great reservoir of language any further in order to express

himself/herself in a more refined and sophisticated manner.

29

Regression

The learner fails to express himself/herself in areas (phraseology, style or vocabulary) that

he or she had mastered at an earlier point in time.

Over generalization

The learner searches for a logical grammar of the TL that would cover every aspect of the

language, or seeks to find every aspect of existing grammars confirmed in the living

language. In doing so, the learner draws on aspects of the target language already earned

and overuses them.

Over elaboration

The learner wants to apply complex theoretical structures to contexts that may call for

simpler expression.

Interference from L1 (or L3), with phonological interference being the most common

example. Syntactic interference and semantic interference are also possible, e.g., so-called

false friends. These are words that exist in the source language as well as in the target

language. However, their meaning or use might differ substantially, as in the German

"Figur" vs. the French "figure" (="face"), or the English "eventually" vs. the German

"eventuell" (="possibly").

30

Variable input

This refers to the quality of education in the TL, the variety and extent of exposure to the

TL and the communicative value of it to the learner. This is why the design of learning

material and contact with many TL native speakers plays a vital role in learning a new

language.

Organic and/or cumulative growth

There can be unstructured, widely dispersed input which is not always predictable. This is

structured by the learner in progressive building blocks.

31

Lecture seven

Principal language disorders and examples of language disorders/errors

The present lecture tackles the following points:

- Language disorders.

- Principal language disorders.

- Examples of language disorders/errors.

Sources/References

- Bauer, Laurie (2007). The Linguistics Student's Handbook.

- Ipsen, Guido (1999). The Interactive MultiMedia Linguistics for Beginners Textbook.

Language disorders

The principal language disorders are aphasia, anomia, dyslexia, and dysgraphia. Usually,

language disorders are caused by injuries or malfunctions of the brain. Neurologists were

able to locate those areas of the brain that play a central role in language production and

comprehension by examining patients whose brains had suffered damages in certain areas.

APHASIA

This is a disorder in the ability to process or produce spoken language. Two scientists,

Broca and Wernicke, were able to locate two areas of the brain responsible for these

activities.

• Broca's area. In 1864 the French surgeon Broca was able to locate a small part of the

brain, somewhat behind our left temple. This area is responsible for the organization of

language production. If it is damaged, the patient usually knows what (s)he wants to say but

can't organize the syntax. More nouns than verbs are used. There is hesitant speech and

poor articulation. Comprehension and processing are usually not impaired.

• Wernicke's area. Carl Wernicke identified another type of aphasia in 1874. He located a

part of the brain behind the left ear where he found comprehension of language to take

place. Speech production and syntax are generally possible with Wernicke's patients.

However, comprehension and, also to some extent, production is impaired, and patients

show the tendency to retrieve only general nouns and nonsense words from their mental

lexicon and to lose specific lexis, or vocabulary. They do not seem to be aware of their

problem and thus do not react to treatment easily.

32

Both Broca's and Wernicke's areas are located in the left half of the brain. The executive

centers, however, are located in the right hemisphere. A separation of the two halves of the

brain effects the capability of converting linguistic information into action, or vice versa.

Apart from the types of aphasia identified by Broca and Wernicke, there are also other

kinds of aphasia.

• Jargon. In "neologistic jargon aphasia", patients can only produce new approximations of

content words (nouns), they will never hit the exact word. In general, messages are hard to

understand and often completely incomprehensible or not decodable by listeners, although

the speakers have good syntax.

• Conduction. Patients understand what is being said to them, however, they are unable to

repeat single words and make other errors when speaking. However, they are aware of their

errors. In this kind of aphasia, it is neither Broca's nor Wernicke's area that is damaged, but

the connection between them.

• In transcortical aphasia, there is a weakness in comprehension. The best preserved feature

is the ability to repeat heard phrases. Therefore, the processing of language is impaired, but

the patient is able to hear and pronounce the acoustic chain.

• Global aphasia has the worst effects on the patient. All language abilities are seriously

impaired in this case. Both Wernicke's and Broca's areas are damaged.

33

ANOMIA

Anomia is the loss of access to certain parts of the lexis. Anomia patients are unable to

remember the names of things, people, or places. There is often a confusion between

semantically related words. Undoubtedly, you will have experienced this phenomenon

yourself! We are all prone to it at times. It usually increases with age, although pure anomia

is a much more acute state and is not related to aging.

DYSLEXIA

This is a disorder of reading where the patient is not capable to recognize the correct word

order. Patients also tend to misplace syllables. There is also an over generalization of the

relation between printed words and their sound value. For example, a patient may transport

the pronunciation of "cave" = /keIv/ to "have" = */heIv/ instead of /h?v/.

DYSGRAPHIA

Dysgraphia is a disorder of writing, mainly spelling. Patients are not able to find the correct

graphemes when putting their speech into writing. Also, they are not able to select the

correct order of graphemes from a choice of possible representations.

34

Errors

Errors in linguistic production are not a malfunction caused by disease. They occur

frequently and are part of the communication process. Here are examples of the usual types

of errors made:

• Anticipation. Sounds appear in words before their intended pronunciation: take my bike ?

bake my bike. This error reveals that further utterances were already planned while

speaking.

• In preservation errors, the opposite is the case. Sounds are "kept in mind" and reappear in

the wrong place: pulled a tantrum ? pulled a pantrum

• Reversals (Spoonerisms) are errors where sounds are mixed up within words or phrases:

harpsichord ? carpsihord

• Blends occur when two words are combined and parts of both appear in the new, wrong

word: grizzly + ghastly ? grastly

• Word substitution gives us insight into the mental lexicon of the speaker. These words are

usually linked semantically. Give me the orange. ? Give me the apple.

• Errors on a higher level occur when the structural rules of language above the level of

pronunciation influence production. In the below example, the past tense of "dated" is

overused. The speaker "conjugates" the following noun according to the grammatical rules

of "shrink-shrank-shrunk": Rosa always dated shrinks ? Rosa always dated shranks.

• Phonological errors are the mixing up of voiced and unvoiced sounds: Terry and Julia

?Derry and Chulia

• Force of habit accounts for the wrong application of an element that had been used before

in similar contexts. For example, in a television broadcast by BBC, the reporter first spoke

about studios at Oxford university. When he then changed the topic to a student who had

disappeared from the same town he said: "The discovery of the missing Oxford studio"

instead of "The discovery of a missing Oxford student."

35

Lecture eight

Social context as affecting language use. Lexical Semantics, Reference, Pragmatics

The present lecture tackles the following points:

- Social context as affecting language use.

- Grammatical vs. Pragmatic meaning.

- Sentence vs. Utterance.

- Lexical Semantics, Reference, Pragmatics.

Sources/References

Charles F. Meyer (2009). Introducing English Linguistics

Introduction

In this lecture, we try to explore how the social context in which language is used affects

human communication. It begins with a discussion of the need to distinguish grammatical

meaning from pragmatic meaning, i.e. meaning as a part of our linguistic competence vs.

meaning derived from our interactions in specific social contexts. Because the discussion in

this lecture will be centered on pragmatic meaning, it is also necessary to distinguish a

sentence from an utterance, the primary unit upon which the study of pragmatic meaning

is based. These are basic notions or terms when studying what is linguistically called

speech act theory, a theory that formalizes the notion that what people actually intend their

utterances to mean is often not clearly spelled out in the words that they speak or write.

In July of 2005, John Roberts was nominated to be a justice on the Supreme Court of the

United States. Newspaper accounts of the nomination described Roberts as being a “strict

constructionist”: someone who applies a literal interpretation to the language of the United

States Constitution. Commenting on this description of Roberts, the noted literary and legal

theorist Stanley Fish (2005) argued that Roberts was not really a proponent of “strict

constructionism” but of “textualism,” the belief that interpretation involves “sticking to the

meanings that are encoded in the texts and not going beyond them.” To illustrate the

limitation of this view of interpretation, Fish notes that if a wife asks her husband Why

don’t we go to the movies tonight?

The answer to that question depends on the history of the marriage, the kind of relationship

they have, the kind of person the husband thinks the wife is. The words themselves will

not produce a fixed account of their meaning [emphasis added].

What Fish is arguing in this statement is that communication does not exist in a vacuum: to

engage in a conversation, for instance, we do not simply decode the meanings of the words

that people speak but draw upon the larger social context in which the conversation takes

place. To understand the larger point that Fish is making, it is first of all necessary to

distinguish grammatical meaning from pragmatic meaning.

36

Grammatical vs. pragmatic meaning

In his description of the sentence Why don’t we go to the movies? Stanley Fish is

distinguishing meaning at two levels. On one level, how we interpret the sentence is

determined by the meaning of the individual words that it contains. To make sense of this

sentence, we need to know, for instance, what words such as go and movies mean; that we

refers outside the text to the speaker and addressee; that the indicates that a specific movie

is being referred to; and so forth. At this level, we are within grammar studying what is

known as semantics: how words have individual meaning (lexical

semantics) and can be used to refer to entities in the external world (reference). Semantics

is one component of grammar, and is therefore part of our linguistic competence. As Fish

correctly observes, however, interpretation of a sentence goes beyond understanding its

meaning at the level of grammar. We need to understand the entire social context in which a

sentence was uttered, a different level of interpretation that is studied within pragmatics,

which explores the role that context plays in the interpretation of what people say.

Although many linguists agree with this view of the relationship between grammar and

pragmatics, others believe that the boundary between grammar and pragmatics is not this

discrete. For instance, Fillmore (1996: 54) notes that “this view yields a subtractive view of

pragmatics, according to which it is possible to factor out of the full description of linguistic

activities those purely symbolic aspects which concern linguistic knowledge independently

of notions of use or purpose.” The problem with making a clear divide between grammar

and pragmatics, Fillmore argues, is that this view ignores the role that conventionality plays

in language, i.e. that our interpretation of a sentence such as Could you please pass the salt?

as a polite request is as much a matter of the social context in which this sentence is uttered

as the fact that in English, yes/no questions with verbs such as can or could have been

conventionalized as markers of polite requests (e.g. Can you spare a dime? Could you help

me with my homework?).

37

Sentence vs. utterance

Many people mistakenly think that complete sentences are the norm in both speech and

writing. However, as Carter and Cornbleet (2001: 3) correctly observe, “We do not set out

to speak in sentences – in fact, in informal speech we rarely do that – rather, we set out to

achieve a purpose which may or may not require full, accurate sentences.” To illustrate this

point, consider the short excerpt below taken from an actual conversation:

Speaker A: Lots of people are roller skating lots of people do rollerblade.

Speaker B: Just running around the city.

Speaker A: Uh mainly in Golden Gate Park.

Sentence vs. utterance

Speaker A’s first turn contains two grammatical sentences: constructions consisting of a

subject (lots of people in both sentences) and a finite verb (are and do, respectively). In

contrast, Speaker B’s turn and Speaker A’s second turn do not contain sentences: B’s turn

contains a construction centered around the verbal element running; A’s turn is a

prepositional phrase. But while these turns do not contain complete sentences, they are

nevertheless meaningful. Implied in B’s turn, for instance, is that those who are roller

skating are “running around the city” and in A’s turn that they are skating “mainly in

Golden Gate Park.” Therefore, when discussing pragmatics, linguists tend to avoid labels

such as sentence, instead preferring to describe the constructions under discussion as

utterances, a category that includes not just sentences but any construction that is

meaningful in the context in which it occurs.

38

Lecture nine

Text types & language functions

Sources/References

- Malmkjr, Kirsten (1995) The Linguistics Encyclopedia.

- Newmark, Peter (1988) A Textbook of Translation.

Text Types:

Correlating a text type with the language functions the text performs is very important in

understanding the text. It is important for readers, learners and, undoubtedly, translators.

Generally language functions refer to type of linguistic structures and the

information/meanings they carry included in a text. Scholars have tried to classify texts–

known as text typology– according these language functions. The idea of classifying texts

according to their language functions originally started with Karl Bühler's organon model

(1934) which divides language functions into three types:

- Referential (i.e., informative)

- Expressive

- Appellative (the use of language to make the receiver feel or do something, corresponding

to 'operative' in Reiss's– another German scholar– terminology).

Reiss - the German scholar referred to above - has even tried to systematize the process of

translation, and its evaluation, by dividing texts into three types according to the language

functions they assume, hence choosing the translation method that suites each type.

However, her text typology has been criticized for its confinement to just three types of

language functions. It is a weakness that later scholars have tried to overcome.

Nord (1997, 40) - being one of the founders of functionalism.

observes:

Here we will add a fourth function, which seems to be lacking in Buhler’s model: the phatic

function, which we adapt from Roman Jakobson’s model of language functions (1960).

These four basic types of function can be broken down into various sub-functions.

Types of language functions

1- The Referential Function

The referential function of an utterance involves reference to the objects and phenomena

of the world or of a particular world, perhaps a fictional one. It may be analyzed

according to the nature of the object or referent concerned. If the referent is a fact or state

of things unknown to the receiver (for example, a traffic accident) the text function may

consist in informing the reader; if the referent is a language or a specific use of language,

the text function may be metalinguistic; if the referent is the correct way of handling a

washing machine or of bottling fruit, the text function may be directive; if it is a whole

field that the receivers are to learn (for example, geography) the function may be

didactic. Of course, this list of sub-functions cannot pretend to be exhaustive…

The referential function is mainly expressed through the denotative value of the lexical

items present in the text. Certain references are presumed to be familiar to the receivers

and thus not mentioned explicitly.

39

The referential function is oriented toward objects in real or fictitious worlds. To carry

out the referential function, the receiver must be able to coordinate the message with their

model of the particular world involved. Since world models are determined by cultural

perspectives and traditions, receivers in the source culture may interpret the referential

function differently to those in the target culture. This gives rise to significant translation

problems.

Clearly, the referential function depends on the comprehensibility of the text. The

function poses problems when source and target readers do not share the same amount of

previous knowledge about the objects and phenomena referred to, as is often the case

with source-culture realities or realia.

2- The Expressive Function

Unlike Reiss's text typology, where the expressive function is restricted to the aesthetic

aspects of literary or poetic texts, the expressive function in my model refers to the sender's

attitude toward the objects and phenomena of the world. It may be subdivided according to

what is expressed. If the sender expresses individual feelings or emotions (for example, in

an interjection) we may speak of an emotive sub-function; if what is expressed is an

evaluation (perhaps a government decision) the sub-function will be evaluative. Another

sub-function might be irony. Of course, a particular text can be designed to carry out a

combination of several functions or subfunctions…

The expressive function is sender-oriented. The sender's opinions or attitudes with regard to

the referents are based on the value system assumed to be common to both sender and

receiver. However, in the standard form of intercultural interaction the sender belongs to the

source culture and the receiver belongs to the target culture. Since value systems are

conditioned by cultural norms and traditions, the value system of the source-text author may

be different from that of the target-culture receivers.

This means that an expressive function verbalized in the source text has to be interpreted in

terms of the source-culture value system. If it is verbalized explicitly (perhaps by means of

evaluative or emotive adjectives, as in 'cats are nasty, horrible things!'), the readers will

understand even when they disagree. But if the evaluation is given implicitly ('A cat was

sitting on the doorstep') it may be difficult to grasp for readers who do not know on what

value system the utterance is based (is a cat on the doorstep a good or a bad thing?). Many

qualities have different connotations in two different cultures, as can be observed in

national stereotypes. If said by a German, the sentence 'Germans are very efficient' probably

expresses a positive evaluation, yet it might not be so positive if said by a Spaniard.

Example: In India if a man compares the eyes of his wife to those of a cow, he expresses

admiration for their beauty. In Germany, though, a woman would not be very pleased if her

husband did the same.

3- The Appellative Function in Translation:

Directed at the receivers' sensitivity or disposition to act, the appellative function ('conative'

in Jakobson's terminology) is designed to induce them to respond in a particular way. If we

want to illustrate a hypothesis by an example, we appeal to the reader's previous experience

or knowledge; the intended reaction would be recognition of something known. If we want

40

to persuade someone to do something or to share a particular viewpoint, we appeal to their

sensitivity, their secret desires. If we want to make someone buy a particular product, we

appeal to their real or imagined needs, describing those qualities of the product that are

presumed to have positive values in the receivers' value system. If we want to educate a

person, we may appeal to their susceptibility to ethical and moral principles.

Direct indicators of the appellative function would be features like imperatives or rhetorical

questions. Yet the function may also be achieved indirectly through linguistic or stylistic

devices that point to a referential or expressive function, such as superlatives, adjectives or

nouns expressing positive values. The appellative function may even operate in poetic

language appealing to the reader's aesthetic sensitivity…

The appellative function is receiver-oriented… While the source text normally appeals to a

source-culture reader's susceptibility and experience, the appellative function of a

translation is bound to have a different target. This means the appellative function will not

work if the receiver cannot cooperate.

4- The Phatic Function in Translation:

The phatic function aims at establishing, maintaining or ending contact between sender and

receiver. It relies on the conventionality of the linguistic, non-linguistic and paralinguistic

means used in a particular situation…

Unconventionality of form strikes the eye and makes us think the author had a special

reason for saying something precisely in that way. A phatic utterance meant as a mere 'offer

of contact' may be interpreted as referential, expressive or even appellative if its form does

not correspond to the receiver's expectation of conventional behaviour. The phatic function

thus largely depends on the conventionality of its form. The more conventional the

linguistic form, the less notice we take of it. The problem is that a form that is conventional

in one culture may be unconventional in another.

Another feature of phatic utterances is that they often serve to define the kind of

relationship holding between sender and receiver (formal/informal,

symmetrical/asymmetrical). Here conventionality of form also plays an important part…

Except for purely phatic expressions or utterances, texts are rarely mono functional. As a

rule we find hierarchies of functions that can be identified by analyzing verbal or nonverbal function markers.

Summary

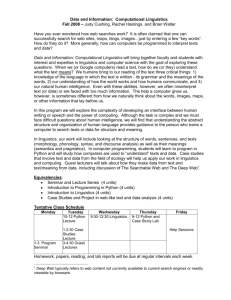

In regard to the above demonstration of language functions and hence text typology,

consider the figure below (Newmark: 1988: 40) which pinpoints four main elements: (a) the

language function; (b) the core of the translational process; (c) the author's status; (d) the

text type:

41

It is worth mentioning in regard to the above figure that Newmark has alternatively used the

terms 'informative' and 'vocative' as referents for Nord's 'referential' and 'appellative' though

both have depended on the same source, "Bühler's functional theory of language" (1934).

42

Lecture ten

Text Linguistics as a new subfield of linguistics

The present lecture tackles the following points:

- 'Text Linguistics' as a new subfield of linguistics.

- What is a text?

- The principles of textuality.

- Cohesion, coherence, intentionality, acceptability, informativity, situationality, and

intertextuality

Sources/References

- Malmkjr, Kirsten (1995). The Linguistics Encyclopedia.

- Ipsen, Guido (1999). The Interactive MultiMedia Linguistics for Beginners Textbook.

Text linguistics

What is text linguistics?

Some have dealt with the term "text" quite freely although the use of this term is not quite

that simple. None of the branches of linguistics known to us regards the complete entity of

texts as their primary subject matter in the way text linguistics does. Instead, they focus

rather on, e.g., the nature and function of morphemes and words within texts on a very

abstract level. Sentences are examined with syntax, and word as well as sentence meaning

are discerned by semantics. Although all of these domains deal with parts of texts, namely

sounds, words and sentences, they fail to generate a broader understanding of the

substantial and unique import of texts as such.

This we can only understand when observing how texts are produced, presented, and

received…

Text linguistics

In what way do processes in text production, that is: decision and selection and their impact

on communicative interaction generate structure?' This approach to linguistics, that is of

regarding complete texts as entities of inquiry, is still fairly young, having come into being

only in the 1970's. It is also referred to as text linguistics. However, the origin of this regard

for texts goes way back to Ancient Greece and Rome, where philosophers founded the

science of rhetoric. This science cultivates speech and examines the complete text for its

applicability for an oral presentation and its overall effect and persuasive potential. As a

discipline rhetoric received high esteem and was acknowledged as one of the main branches

of science. This cultivation for spoken speech continued on even up to the Middle Ages,

where the church implemented it for its aims. As a science of texts, rhetoric shares many

concerns with text linguistics. Some assumptions are:

• The accessing and arranging of ideas is open to systematic control.

• The transition from idea to expression can be consciously trained.

• Among the various texts which express a given configuration of ideas, some are of a

higher quality than others.

43

• Texts can be evaluated in terms of their effects on the audience.

• Texts are vehicles of purposeful interaction."

You may remember some of these notions from our chapter on pragmatics, however, while

the emphasis then was on the use of language, it is now the whole text which is of interest.

The principles of textuality

What constitutes a text? Usually, we do not think about how we produce or understand

speech, i.e. the texts for speech. Still, there are basic principles that structure texts and it is,

for example, thanks to our intuitive compliance to these principles that we still know what a

discussion is all about even after ten minutes of talking. Also, you do not have to return to

the first pages of a book whenever you start reading the next chapter, because you know

that the text proceeds. You can even refer to other texts written in other books or taken from

other media, such as newspapers. These constructive elements of texts are known as

textuality. They help us in recognizing where texts start, where they end and how to

perceive a text as an entity. (Consider the following seven elements which should be

included in any entity called 'text').

1. Cohesion

Texts are regarded as stable systems the stability of which is upheld by a continuity of

occurrences. This means that elements re-occur throughout the text system and can thus be

interrelated. Our short term memory does not lend itself for storing information on a larger

scale. The continuity of occurrences thus serves to refresh this short term memory, creating

a basis for a long term memory to function. Whereas cohesion within a sentence is

constituted by syntax, it is this factor of the continuity of occurrences that makes for

cohesion within a text. As you can already guess, cohesion is established by means of

syntax. The way sentences are constructed help in establishing cohesion. The following

features belong to the re-occurrences that make for the cohesion of texts:

Recurrence

The direct repetition of elements is called recurrence. It can fulfill many functions.

However, whenever applied, the phenomenon of recurrence must be derived from a

comprehensible motivation. The phrase "I met Sally and I met Sally.", for instance, seems

awkward as there is just no reason for repeating the same element…

Junction

Events and situations are combined in texts. This action is called junction. Junctive

expressions are commonly known as conjunctions.

- Conjunctions link things of the same status: "and".

- Disjunctions link elements of an alternative status: "or".

- Contrajunctions link elements of the same status which are incompatible: "but".

- Subordinators link things where the status of one depends on the other: "because", "since".

44

2. Coherence

Whereas cohesion is the syntactical means of keeping a text together, there is also the

meaning which interweaves the whole of a text. This meaning principle is called the

coherence of a text. Coherence can happen only under the condition of a set of

prerequisites. For one, speakers must have a common knowledge base that they draw from.

Secondly, there must be a context which is important in respect to the meaning (as we have

seen in the chapter on pragmatics, the meaning of phrases depends on the intention and

situation. Concepts in texts may hence change their meaning regardless of their sememe).

3. Intentioality and acceptability

Let's rehearse the basic principles here:

Cohesion and coherence are the most important principles of textuality. However, there are

texts which are neither fully cohesive nor coherent. Hence, we must take the attitude of the

language users toward the text into consideration. What is their intention? Presumably there

is some planning involved in order to put the intention into words. Speakers may fail to clad

their intention into a pattern both cohesive and coherent:

"You know, I – where am I? Ah, yes, last night I visited Dan, and he – but you do know

Dan, don't you?"

We all know such inconsistent sentences from our everyday experience. They derive from

the change of intention during the utterance. The change may be caused by an internal

reflection or by some external event, such as a frowning listener. Nevertheless, when

listening and talking we follow a cooperative principle, which, in turn, places the text into

an acceptable framework, even if their surface structure neglects cohesion and coherence.

4. Informativity

Informativity refers to whether the contents of a text is new or whether it was expected by

the receiver. We differentiate here with the following features:

- Probability. Is the utterance probable? A sentence like: "I like Chinese food" is quite

probable as far as statistical probability of correct sentences is concerned. But a sentence

such as "All you foul dishes of the degenerate West, you cannot compete to my favorites

from the East!" is much too unique to be statistically probable. Another aspect is contextual

probability. When talking about food, for instance, a sentence like "And the new BMW is

really nice to look at." is grossly out of context and as thus improbable.

- Orders of informativity. If the predictability of intention, cohesion, and coherence is high,

we speak of first-order informativity. An example is the "stop" traffic sign, the content and

structure of which is very unambiguous and conventionalized. First-order occurrences are

also called defaults: they are used very often, such as certain phrases. But in order to make

texts more interesting, informativity of second or third order must appear. Usually, texts

consist more or less of second-order occurrences. These are upgraded or downgraded in

order to produce either more predictable or more interesting bits of text. In a short story or

novel, the author will rather use downgraded, unpredictable text. This will keep the reader

focused on the book.

45

- Text types. The rate of informativity differs in the many various text types, such as

literary, poetic, and scientific texts. Naturally, in poetry, the number of third-order

occurrences is much higher than in scientific texts.

5. Situationality

Texts must be relevant to the current situation in which they appear. We distinguish

between the following:

- Situation monitoring is being performed if the primary function of a text is to describe a

given situation as best as possible.

- Situation management means that a text is designed to fit into a situation as best as

possible.

Although texts have to be relevant to the situation in which they appear, the situation does

not have to be a real situation, i.e. it can be fictional. For example, in drama the audience is

drawn into a situation generated on the stage. Thus, when Hamlet says "All's not well...",

his monologue naturally does not mean that the audience is in Denmark, the setting of the

play. In short, literary texts have the prerogative to present alternative situations in which

they fit quite well.

6. Interextuality

No text is really independent, i.e. all texts relate to others in one way or another. The

expressions textual field or the text universe have been created by scholars to refer to this

textual network.

The principle of intertextuality is that the structure (i.e. those principles listed above) of

texts is determined largely by texts that have been received by authors or readers prior to

that. Citations or a re-use of texts is one of the more obvious ways in which this principle

applies. But intertextuality can also be detected in more subtler forms and occurs between

various text types as well.

In the narrower sense of texts within the framework of text linguistics, we speak of

intertextuality as the phenomenon of interference between various texts in a conversation.

Situation management and monitoring depend heavily on other texts which have been

uttered in the conversation. A receiver does not remain uninfluenced by these uttered texts

and interrelates them with his own textual production.

Summary

De Beaugrande and Dressier (1981: 3) define text as a communicative occurrence which

meets seven standards of textuality, namely cohesion and coherence, which are both textcentred, and intentionality, acceptability, informativity, situationality, and

intertextuality, which are all user-centred. These seven standards function as the

constitutive principles which define and create communication.

46

Lecture eleven

Semiotics: its relation to linguistics

The present lecture tackles the following points:

- Semiotics: its relation to linguistics

- Saussure

- Peirce

Sources/References