Historical Thinking Presentation

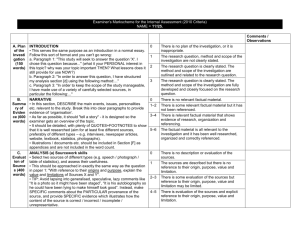

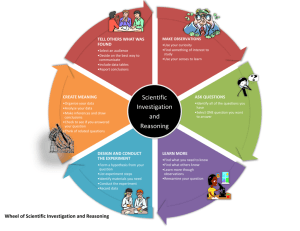

advertisement

Historical Thinking: Changing Classrooms for Changing Times Note to the Reader: I have taught 8 th grade U.S. history for 8 years now. I knew at the end of the May 2014 school year that if I did not do something drastic in my classroom that I would not be teaching much longer. I felt I had hit a brick wall. I thought maybe it was what I taught, where I was at, or even the age of the students. I put in for a transfer to the high school and did not get the job. I knew after the interview, I was no where near prepared to teach high school. In June, the people that I am closest to were honest with me, and told me that I was the only one that had the control and power in my own classroom. If I was tired of the way I was teaching, to change it. If I was tired of having the same state test scores to change what I was doing. This resonated with me and I acted bigger than I thought I ever would. When Historical Methods started I chose my classroom as my research topic, to be accountable for the changes I was making in my classroom. Whether successful or not, I had to put these changes into place and stay with it, because now I had a media project due. My biggest fear has been; are these changes too drastic, and yes…are the students going to test well if I turn my classroom over to them and me work as their facilitator? This was scary for me, because I make small (emphasis on small) changes each year, but nothing of this magnitude. The results have proved positive beyond my wildest dreams, and I am now having the best year I have ever had teaching 8 th grade U.S. history. I am thankful I did not get the job at the high school. It forced me to reevaluate my choices, and make a change for my students, to create an environment of success that my students have so far, loved. Education Week Teacher Education Week Teacher According to historical thinking advocates, lecture has a time and place in the classroom. However, a classroom built around lecture can be considered dull, and an easy way to package information, instead of making the students do the work themselves. In these types of classrooms, experts say, that students copy information from a PowerPoint, or overhead. This creates a classroom where students are not engaged with the information. Engaging the information means using the information to create arguments and come up with solutions. Here is an example of a lecture centered classroom. (This video is used in many of my staff development meetings) Ferris Bueller’s Day Off Bruce A. Lesh, “Why Don’t You Just Tell Us the Answer?” Teaching Historical Thinking in Grades 7-12 (Portland Maine: Stenhouse Publishers, 2011) 125-126 There are many different definitions on how to create historical thinkers, but the idea in all of them is the same: To use sources in the classroom to create curiosity, asses evidence (historical inquiry), and develop a response to an effective historical question. What is Historical Thinking? Stanford: History Education Group Disciplinary concepts for Historical Thinking lessons: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. Causality Chronology Multiple Perspectives Contingency Empathy Change and Continuity over Time Influence / Significance / effect Contrasting Interpretations Intent / Motivation Causality: This is going to be a study of why things happen. Usually at the end of chapters in textbooks the summary questions stress causality, or having students study why things happen . This encourages students to focus on an interpretation of who or what caused an event. Chronology: When students put things in chronological order they are able to create an argument for causality. Multiple Perspectives: This is when a teacher presents to students an array of documents from a single event. It is important to keep the documents narrow to the time period. Diaries, government documents, or pictures for this type of lesson create an interpretation of the people’s thoughts that lived during this time period. If you provide films, textbooks, or things more current you run the risk of students trying to interpret different historiography and this not the purpose of multiple perspectives. Contingency: Something dependent of a possible outcome. Teaching contingency helps students learn to how to predict a future outcome. Empathy: The understanding of the way people in past institutions, social practices, or actions saw things. Empathy means trying to make sense of past actions and the reasons for them. It is not trying to become another person such as roleplaying activities in the classroom *Empathy ask questions such as “Why did an individual or group of people . . . act in a certain way?” (Lesh, 155) Change and Continuity over Time: This allows students insight into how and why the telling of historical events change over time. (How have historians changed their views on historical events) Influence / Significance / Effect: Once an investigation of an event takes place, students are then able to formulate ideas, arguments and conclusions about the influence, significance and the effect it had on the time period and how it effects the world today. *What are the limitations and opportunities made possible by past decisions? Contrasting Interpretations: When students are provided multiple perspectives they realize that history is not just a set of correct answers but a rich landscape of historical interpretations. They learn that historical interpretation is also subject to change depending of the days issues and as new information is uncovered. Intent vs. Motivation: Intention is the will you have to do something. *EX: I want to do a sport. Motivation is the inside voice that pushes you to do it. *EX: I want to do a sport because I want to be fit. Students look for intent and motivation to historical figures while completing their investigations. It is sometimes hard to distinguish between the two. The Historical Thinking Model: 1. A focused content driven question (questions, not answers, should drive instruction) 2. Initiate the investigation (access prior knowledge, provide background information) 3. Conduct the investigation (have relevant and conflicting sources) 4. Report interpretations and class discussion (share various interpretations and ideas 5. Debrief student investigations 6. Assess student comprehension 1. Focus Content Driven Question: The question should be though provoking, and help deepen a student’s understanding of the content. Question should be central to the curriculum of the teacher. Example Question: (Early Republic Unit – John Adams Presidency) Do Presidents have the right to suspend civil (individual) liberties in times of war and crisis in the United States? 2. Initiate the investigation: Hook the student's attention and then access prior knowledge (3 parts) Part 1: Bellringer – Project Sedition Act and answer these questions: What is this document saying? Does it violate the Constitution? Defend your answer with proof. 2. Initiate the investigation: CONT. Part 2: Have students in groups of three read one part of a civil liberties timeline then discuss the common theme. In their groups they come up with the common themes from these summaries, then discuss as a class whether it is appropriate to suspend individual liberties when the United States is in crisis. 2. Initiate the investigation: CONT. Part 3: Hand out the Graphic Organizer. Read the background information on John Adams Presidency. Summarize the background information, then write it in the middle triangle. As a group, then as a class, they will discuss their background knowledge and what was carried over from Washington’s Presidency. When they discuss as a class, lead class with appropriate questioning 3. Conduct the investigation: 1. Now go back and discuss the bellringer. What were some of the answers and talk about whether it is Constitutional. (By this time the students know the Bill of Rights and the Supreme Court’s job. They should be able to defend their answers. 2. Hand out the primary sources (the laws passed during Adam’s presidency) and have the students divide them up. Once they have finished reading, summarizing and putting the information in the chart, they share their info for the other students to fill in their charts. 4&5 Report and debrief interpretations Class discussion, share various interpretations and ideas Go over documents and notes as a class. 6. Assess student comprehension: Here the students wrote an essay using the information they had for Adam’s presidency. They will give opinions and defend their answers based on classroom notes, discussions, primary sources, and background knowledge. My Classroom: Critical Thinking Boards “I know you think that but where is the evidence to support your answer?” Text, Context, and Subtext: These are the themes that are throughout the lesson. Specific questions should be asked in order to guide the information the students are processing . Bruce A. Lesh, “Why Don’t You Just Tell Us the Answer?” Teaching Historical Thinking in Grades 7-12 (Portland Maine: Stenhouse Publishers, 2011) 39 Text: 1. What is visible/readable? 2. What information is provided by the source? Ibid,. 39 Context: 1. What was going on during the time period? 2. What background information do you have that helps explain the information found in the source? Ibid,. 39 Subtext: Ask questions about the following: 1. What is between the lines? 2. Author: Who created the source, and what do we know about that person? 3. Audience: For whom was the source created? 4. Reason: Why was this source produced when it was? Ibid,. 39 Bibliography Ferlazzo, Larry. “Response: Teaching History By Encouraging Curiosity” Education Week Teacher. (May 31, 2014) accessed October 1, 2014, http://blogs.edweek.org/teachers/classroom_qa_with_larry_ferlazzo/2014/05/response_teaching_history_by_encouragin g_curiosity.html *Editorial Projects in Education is an independent, nonprofit publisher of Education Week. EPE's mission is to raise awareness and understanding of critical issues facing American schools. Lesh, Bruce A. “Why Don’t You Just Tell Us the Answer?” Teaching Historical Thinking in Grades 7-12. Portland Maine: Stenhouse Publishers, 2011. *This book is a guide for teachers wanting to use the historical thinking model in their classroom. He goes step by step using different teaching standards for each chapter to show how historical thinking strategies can be used successfully in the classroom Stanford History Education Group. “Charting the Future of Teaching the Past.” http://sheg.stanford.edu/ This website was put together by Stanford Universities' Historical group. It offers lessons on historical thinking, and details how to implement it into the classroom. Teachinghistory.org. “What is Historical Thinking?” http://teachinghistory.org/historical-thinking-intro Teachinghistory.org is designed to help K–12 history teachers access resources and materials to improve U.S. history education in the classroom. With funding from the U.S. Department of Education, the Center for History and New Media (CHNM) has created Teachinghistory.org with the goal of making history content, teaching strategies, resources, and research accessible Wineburg, Sam. Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001