Poetry Packet: Poems on Aging, Death, Depression

advertisement

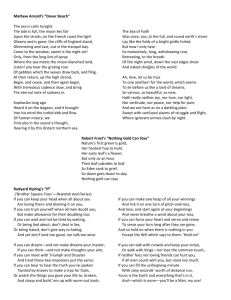

Poems on Aging, Death, Depression, Grief, Suicide, & War 2. Adamshick, Carl: “Before” 3. Auden, W.H.: “Funeral Blues” 4. Bridgford, Kim: “Jumping” 5. Brown, Derrick C.: “Instead of Killing Yourself” 6. Crum, Robert: “A Child Explains Dying” 7. Dickinson, Emily: “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” 8. Digges, Deborah: “Trapeze” 9. Frost, Robert: “Acquainted with the Night” 10.Giovanni, Nikki: “Quilts” 11. Holt, Jeff: “Waiting Room” 12. Jarrell, Randall: “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” 13. Kenyon, Jane: “The Blue Bowl” 14. McGough, Roger: “Let Me Die a Youngman’s Death” 15. Mitchell, Susan: “The Dead” 16. Pastan, Linda: “Departures” 17. Pastan, Linda: “The Hat Lady” 18. Pastan, Linda: “Vertical” 19. Plath, Sylvia: “Lady Lazarus” 21. Sexton, Anne: “The Truth the Dead Know” 22. Sexton, Anne: “Wanting to Die” 23. Thomas, Dylan: “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night” 24. Turner, Bryan: “AB Negative (The Surgeon’s Poem)” 25. Turner, Bryan: “Eulogy” 26. Updike, John: “Dog’s Death” and “Another Dog’s Death” Further Exploration: “The Addict” by Anne Sexton “Thanatopsis” by William Cullen Bryant “Death Be Not Proud” by John Donne This packet belongs to __________________________________________. If found, please return to B-16 or Mrs. Garcia’s mailbox in B House office. Page 1 of 26 Before CARL ADAMSHICK (1969- ) He was born in Toledo, OH. I always thought death would be like traveling in a car, moving through the desert, the earth a little darker than sky at the horizon, that your life would settle like the end of a day and you would think of everyone you ever met, that you would be the invisible passenger, quiet in the car, moving through the night, forever, with the beautiful thought of home. Page 2 of 26 Funeral Blues (also known as “Stop All the Clocks”) W. H. AUDEN (1907-1973) You can hear this read on YouTube in a scene from the 1994 film, Four Weddings and a Funeral. Stop all the clocks, cut off the telephone. Prevent the dog from barking with a juicy bone, Silence the pianos and with muffled drum Bring out the coffin, let the mourners come. Let aeroplanes circle moaning overhead Scribbling in the sky the message He is Dead, Put crêpe bows round the white necks of the public doves, Let the traffic policemen wear black cotton gloves. He was my North, my South, my East and West, My working week and my Sunday rest My noon, my midnight, my talk, my song; I thought that love would last forever, I was wrong. The stars are not wanted now; put out every one, Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun. Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood; For nothing now can ever come to any good. (published 1936) Page 3 of 26 Jumping KIM BRIDGFORD (You can hear her read this at Measure online.) — September 11, 2011 Sometimes I think of them, when I am kept Awake at night. It was a workday morning When they died, an ordinary morning when they leapt. They made it look so easy, therefore earning Our respect, like a complicated skill. You can forget it was not easy at all. They didn’t seem to pause. Like cherubim — The office staff, accountants, businessmen — Within the ash of morning, they would glisten, Remembering that love’s a crucible, And wishing — as did we — for a hand (something!) To tap the heavens, see if God’s at home. And fell. Such quiet in their terror-song. We could not look away, watched far too long. Page 4 of 26 Instead of Killing Yourself DERRICK C. BROWN lives in Austin, TX. Wait until a year from now where you say, “Holy ****, I can’t believe I was going to kill myself before I etcetera’d… before I went skinny dipping in Tennessee, made my own IPA, tried out for a game show, rode a camel drunk, learned to waltz with clumsy old people, photographed electric jellyfish, built a sailboat from trash, taught someone how to read, etc. etc. etc.” The red washing down the bathtub can’t change the color of the sea at all. From Margie Volume 8, 2009 Page 5 of 26 A Child Explains Dying ROBERT CRUM First you close your eyes. Then you hold your breath. Then, when it gets too heavy to hold, you let it go. And it drops to the floor like a stone. But without a sound. And then your mother comes to the door and calls you, saying, “Come out here this instant! Your breakfast is getting cold.” And then your father comes to the door and calls you, saying, “No son of mine is going to lie in bed all day. No son of mine Is going to be late for school” And then they shake you, and when you don’t move they see the mistake they made and they cry and cry and cry. And then they comb your hair and brush your teeth and dress you in a suit and tie just like for Sunday School And then they bury you in the dirt. And your teacher gives your desk to someone else. And your brothers wear your clothes that you’ll never need again because you’re a little lamb at the feet of Jesus in Heaven—you’re a little wooly thing up in the clouds, going baaa, baaa. 1984. From The Ploughshares Poetry Anthology (1987) Page 6 of 26 Because I could not stop for Death (712) EMILY DICKINSON (1830-1886) She was born in Amherst, MA. Because I could not stop for Death – He kindly stopped for me – The Carriage held but just Ourselves – And Immortality. We slowly drove – He knew no haste And I had put away My labor and my leisure too, For His Civility – We passed the School, where Children strove At Recess – in the Ring – We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain – We passed the Setting Sun – Or rather – He passed us – The Dews drew quivering and chill – For only Gossamer, my Gown – My Tippet – only Tulle – We paused before a House that seemed A Swelling of the Ground – The Roof was scarcely visible – The Cornice – in the Ground – Since then – 'tis Centuries – and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses' Heads Were toward Eternity – Page 7 of 26 Trapeze DEBORAH DIGGES (1950-2009) She was born in Jefferson, Missouri. You can hear her read this poem aloud at poets.org. See how the first dark takes the city in its arms and carries it into what yesterday we called the future. O, the dying are such acrobats. Here you must take a boat from one day to the next, or clutch the girders of the bridge, hand over hand. But they are sailing like a pendulum between eternity and evening, diving, recovering, balancing the air. Who can tell at this hour seabirds from starlings, wind from revolving doors or currents off the river. Some are as children on swings pumping higher and higher. Don't call them back, don't call them in for supper. See, they leave scuff marks like jet trails on the sky Page 8 of 26 Acquanited with the Night ROBERT FROST (1874-1963) Born in San Francisco, CA, he spent much of his time in rural New England. I have been one acquainted with the night. I have walked out in rain—and back in rain. I have outwalked the furthest city light. I have looked down the saddest city lane. I have passed by the watchman on his beat And dropped my eyes, unwilling to explain. I have stood still and stopped the sound of feet When far away an interrupted cry Came over houses from another street, But not to call me back or say good-by; And further still at an unearthly height One luminary clock against the sky Proclaimed the time was neither wrong nor right. I have been one acquainted with the night. Page 9 of 26 Quilts NIKKI GIOVANNI (1943- ) (for Sally Sellers) Like a fading piece of cloth I am a failure No longer do I cover tables filled with food and laughter My seams are frayed my hems falling my strength no longer able To hold the hot and cold I wish for those first days When just woven I could keep water From seeping through Repelled stains with the tightness of my weave Dazzled the sunlight with my Reflection I grow old though pleased with my memories The tasks I can no longer complete Are balanced by the love of the tasks gone past I offer no apology only this plea: When I am frayed and strained and drizzle at the end Please someone cut a square and put me in a quilt That I might keep some child warm And some old person with no one else to talk to Will hear my whispers And cuddle near Page 10 of 26 Waiting Room JEFF HOLT This is the place where families cross their legs And stare, sightless, at unobtrusive art. This is the place where every minute drags Like a dead body heaved onto a cart. A mother clasps her hands, as if in prayer, Then bows her head and curses quietly. A husband thinks that if he’d just seen more His wife would not have needed surgery. Death breathes upon these souls who wait in need Of angels wearing scrubs to proffer grace. All wait alone, and none are reassured By memories of a loved one’s pleading face. In purgatory they await the words Of gods who fail as often as succeed. from The Raintown Review, Vol. #10, Issue #1 (2011?) Page 11 of 26 The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner RANDALL JARRELL (1914-1965) He was born in Nashville, Tennessee. This poem was published in 1945. From my mother's sleep I fell into the State, And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze. Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life, I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters. When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose. “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” is about the death of a gunner in a Sperry ball turret on a World War II American bomber aircraft. Jarrell, who served in the Army Air Forces, provided the following explanatory note: A ball turret was a Plexiglass sphere set into the belly of a B-17 or B-24, and inhabited by two .50 caliber machine guns and one man, a short small man. When this gunner tracked with his machine guns a fighter attacking his bomber from below, he revolved with the turret; hunched upside down in his little sphere. The fighters which attacked him were armed with cannon firing explosive shells. The hose was a steam hose. Page 12 of 26 The Blue Bowl JANE KENYON (1947-1995) She was born in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Like primitives we buried the cat with his bowl. Bare-handed we scraped sand and gravel back into the hole. They fell with a hiss and thud on his side, on his long red fur, the white feathers between his toes, and his long, not to say aquiline, nose. We stood and brushed each other off. There are sorrows keener than these. Silent the rest of the day, we worked, ate, stared, and slept. It stormed all night; now it clears, and a robin burbles from a dripping bush like the neighbor who means well but always says the wrong thing. from Otherwise: New & Selected Poems, 1996 Graywolf Press, St. Paul, Minnesota Page 13 of 26 Let Me Die a Youngman's Death ROGER MCGOUGH (1937- ) Let me die a youngman's death not a clean and inbetween the sheets holywater death not a famous-last-words peaceful out of breath death When I'm 73 and in constant good tumour may I be mown down at dawn by a bright red sports car on my way home from an allnight party Or when I'm 91 with silver hair and sitting in a barber's chair may rival gangsters with hamfisted tommyguns burst in and give me a short back and insides Or when I'm 104 and banned from the Cavern may my mistress catching me in bed with her daughter and fearing for her son cut me up into little pieces and throw away every piece but one Let me die a youngman's death not a free from sin tiptoe in candle wax and waning death not a curtains drawn by angels borne 'what a nice way to go' death Page 14 of 26 The Dead SUSAN MITCHELL At night the dead come down to the river to drink. They unburden themselves of their fears, their worries for us. They take out the old photographs. They pat the lines in our hands and tell our futures, which are cracked and yellow. Some dead find their way to our houses. They go up to the attics. They read the letters they sent us, insatiable for signs of their love. They tell each other stories. They make so much noise they wake us as they did when we were children and they stayed up drinking all night in the kitchen. from The Water Inside the Water, 1994 Page 15 of 26 Departures LINDA PASTAN (1932- ) They seemed to all take off at once: Aunt Grace whose kidneys closed shop; Cousin Rose who fed sugar to diabetes; my grandmother’s friend who postponed going so long we thought she’d stay. It was like the summer years ago when they all set out on trains and ships, wearing hats with veils and the proper gloves, because everybody was going someplace that year, and they didn’t want to be left behind. Page 16 of 26 The Hat Lady LINDA PASTAN (1932- ) She was born in New York, NY. In a childhood of hats— my uncles in homburgs and derbies, Fred Astaire in high black silk, The yarmulke my grandfather wore Like the palm of a hand Cradling the back of his head— only my father went hatless, even in winter. And in the spring, when a turban of leaves appeared on every tree, the Hat Lady came with a fan of pins in her mouth and pins in her sleeves, the Hat Lady came— that Saint Sebastian* of pins, to measure my mother’s head. I remember a hat of dove-grey felt that settled like a bird on the nest of my mother’s hair. I remember a pillbox that tilted over one eye—pure Myrna Loy, and a navy straw with cherries caught at the brim that seemed real enough for a child to want to pick. Last year when the chemicals took my mother’s hair, she wrapped a towel around her head. And the Hat Lady came, a bracelet of needles on each arm, and led her to a place where my father and grandfather waited, head to bare head, and Death winked at her and tipped his cap. * Saint Sebastian was martyred by being shot through with arrows. Page 17 of 26 Vertical LINDA PASTAN (1932- ) Perhaps the purpose of leaves is to conceal the verticality of trees which we notice in December as if for the first time: row after row of dark forms yearning upwards. And since we will be horizontal ourselves for so long, let us now honor the gods of the vertical: stalks of wheat which to the ant must seem as high as these trees do to us, silos and telephone poles, stalagmites and skyscrapers. but most of all these winter oaks, these soft-fleshed poplars, this birch whose bark is like roughened skin against which I lean my chilled head, not ready to lie down. Page 18 of 26 Lady Lazarus SYLVIA PLATH (1932-1963 suicide) She was born in Jamaica Plain, MA. Just FYI: In the Bible (John 11:1-45), Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead. I have done it again. One year in every ten I manage it— A sort of walking miracle, my skin Bright as a Nazi lampshade, My right foot A paperweight, My face featureless, fine Jew linen. Peel off the napkin O my enemy. Do I terrify?— The nose, the eye pits, the full set of teeth? The sour breath Will vanish in a day. Soon, soon the flesh The grave cave ate will be At home on me And I a smiling woman. I am only thirty. And like the cat I have nine times to die. This is Number Three. What a trash To annihilate each decade. What a million filaments. The peanut-crunching crowd Shoves in to see Them unwrap me hand and foot— The big strip tease. Gentlemen, ladies These are my hands My knees. I may be skin and bone, Nevertheless, I am the same, identical woman. The first time it happened I was ten. It was an accident. The second time I meant To last it out and not come back at all. I rocked shut Page 19 of 26 As a seashell. They had to call and call And pick the worms off me like sticky pearls. Dying Is an art, like everything else. I do it exceptionally well. I do it so it feels like hell. I do it so it feels real. I guess you could say I've a call. It's easy enough to do it in a cell. It's easy enough to do it and stay put. It's the theatrical Comeback in broad day To the same place, the same face, the same brute Amused shout: 'A miracle!' That knocks me out. There is a charge For the eyeing of my scars, there is a charge For the hearing of my heart— It really goes. And there is a charge, a very large charge For a word or a touch Or a bit of blood Or a piece of my hair or my clothes. So, so, Herr Doktor. So, Herr Enemy. I am your opus, I am your valuable, The pure gold baby That melts to a shriek. I turn and burn. Do not think I underestimate your great concern. Ash, ash— You poke and stir. Flesh, bone, there is nothing there— A cake of soap, A wedding ring, A gold filling. Herr god, Herr Lucifer Beware Beware. Out of the ash I rise with my red hair And I eat men like air. 23-29 October 1962. From The Collected Poems by Sylvia Plath, Harper & Row. Page 20 of 26 The Truth the Dead Know ANNE SEXTON For my Mother, born March 1902, died March 1959 and my Father, born February 1900, died June 1959 Gone, I say and walk from church, refusing the stiff procession to the grave, letting the dead ride alone in the hearse. It is June. I am tired of being brave. We drive to the Cape. I cultivate myself where the sun gutters from the sky, where the sea swings in like an iron gate and we touch. In another country people die. My darling, the wind falls in like stones from the whitehearted water and when we touch we enter touch entirely. No one's alone. Men kill for this, or for as much. And what of the dead? They lie without shoes in the stone boats. They are more like stone than the sea would be if it stopped. They refuse to be blessed, throat, eye and knucklebone. Page 21 of 26 Wanting to Die ANNE SEXTON (1928-1974 suicide) Since you ask, most days I cannot remember. I walk in my clothing, unmarked by that voyage. Then the almost unnameable lust returns. Even then I have nothing against life. I know well the grass blades you mention, the furniture you have placed under the sun. But suicides have a special language. Like carpenters they want to know which tools. They never ask why build. Twice I have so simply declared myself, have possessed the enemy, eaten the enemy, have taken on his craft, his magic. In this way, heavy and thoughtful, warmer than oil or water, I have rested, drooling at the mouth-hole. I did not think of my body at needle point. Even the cornea and the leftover urine were gone. Suicides have already betrayed the body. Still-born, they don't always die, but dazzled, they can't forget a drug so sweet that even children would look on and smile. To thrust all that life under your tongue!— that, all by itself, becomes a passion. Death's a sad bone; bruised, you'd say, and yet she waits for me, year after year, to so delicately undo an old wound, to empty my breath from its bad prison. Balanced there, suicides sometimes meet, raging at the fruit, a pumped-up moon, leaving the bread they mistook for a kiss, leaving the page of the book carelessly open, something unsaid, the phone off the hook and the love, whatever it was, an infection. Page 22 of 26 Do not go gentle into that good night DYLAN THOMAS (1914-1953) A Welsh poet, he was born in Swansea, Wales. Do not go gentle into that good night, Old age should burn and rave at close of day; Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Though wise men at their end know dark is right, Because their words had forked no lightning they Do not go gentle into that good night. Good men, the last wave by, crying how bright Their frail deeds might have danced in a green bay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight, And learn, too late, they grieved it on its way, Do not go gentle into that good night. Grave men, near death, who see with blinding sight Blind eyes could blaze like meteors and be gay, Rage, rage against the dying of the light. And you, my father, there on the sad height, Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray. Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light. Page 23 of 26 AB Negative (The Surgeon’s Poem) BRYAN TURNER (1967- ) He is a soldier-poet who served for seven years in the U.S. Army, serving in Iraq and Bosnia. He currently lives in California. Thalia Fields lies under a grey ceiling of clouds, just under the turbulence, with anesthetics dripping from an IV into her arm, and the flight surgeon says The shrapnel cauterized as it traveled through her here, breaking this rib as it entered, burning a hole through the left lung to finish in her back, and all of this she doesn’t hear, except perhaps as music — that faraway music of people’s voices when they speak gently and with care, a comfort to her on a stretcher in a flying hospital en route to Landstahl, just under the rain at midnight, and Thalia drifts in and out of consciousness as a nurse dabs her lips with a moist towel, her palm on Thalia’s forehead, her vitals slipping some, as burned flesh gives way to the heat of the blood, the tunnels within opening to fill her, just enough blood to cough up and drown in; Thalia sees the shadows of people working to save her, but she cannot feel their hands, cannot hear them any longer, and when she closes her eyes the most beautiful colors rise in darkness, tangerine washing into Russian blue, with the droning engine humming on in a dragonfly’s wings, island palms painting the sky an impossible hue with their thick brushes dripping green… a way of dealing with the fact that Thalia Fields is gone, long gone, about as far from Mississippi as she can get, ten thousand feet above Iraq with a blanket draped over her body and an exhausted surgeon in tears, his bloodied hands on her chest, his head sunk down, the nurse guiding him to a nearby seat and holding him as he cries, though no one hears it, because nothing can be heard where pilots fly in blackout, the plane like a shadow guiding the rain, here in the droning engines of midnight. From pp. 15-16 of Here, Bullet (2005) Page 24 of 26 Eulogy BRYAN TURNER (1967- ) He is a soldier-poet who served for seven years in the U.S. Army, serving in Iraq and Bosnia. He currently lives in California. You can hear him read this on YouTube. It happens on a Monday, at 11:20 A.M., as tower guards eat sandwiches and seagulls drift by on the Tigris River. Prisoners tilt their heads to the west though burlap sacks and duct tape blind them. The sound reverberates down concertina coils the way piano wire thrums when given slack. And it happens like this, on a blue day of sun, when Private Miller pulls the trigger to take brass and fire into his mouth: the sound lifts the birds up off the water, a mongoose pauses under the orange trees, and nothing can stop it now, no matter what blur of motion surrounds him, no matter what voices crackle over the radio in static confusion, because if only for this moment the earth is stilled, and Private Miller has found what low hush there is down in the eucalyptus shade, there by the river. PFC B. Miller (1980—March 22, 2004) From p. 20 of Here, Bullet (2005) Page 25 of 26 Dog’s Death JOHN UPDIKE (1932-2009) She must have been kicked unseen or brushed by a car. Too young to know much, she was beginning to learn To use the newspapers spread on the kitchen floor And to win, wetting there, the words, "Good dog! Good dog!" We thought her shy malaise was a shot reaction. The autopsy disclosed a rupture in her liver. As we teased her with play, blood was filling her skin And her heart was learning to lie down forever. Monday morning, as the children were noisily fed And sent to school, she crawled beneath the youngest's bed. We found her twisted limp but still alive. In the car to the vet's, on my lap, she tried To bite my hand and died. I stroked her warm fur And my wife called in a voice imperious with tears. Though surrounded by love that would have upheld her, Nevertheless she sank and, stiffening, disappeared. Back home, we found that in the night her frame, Drawing near to dissolution, had endured the shame Of diarrhoea and had dragged across the floor To a newspaper carelessly left there. Good dog. Another Dog’s Death by JOHN UPDIKE For days the good old bitch had been dying, her back pinched down to the spine and arched to ease the pain, her kidneys dry, her muzzle white. At last I took a shovel into the woods and dug her grave in preparation for the certain. She came along, which I had not expected. Still, the children gone, such expeditions were rare, and the dog, spayed early, knew no nonhuman word for love. She made her stiff legs trot and let her bent tail wag. We found a spot we liked, where the pines met the field. The sun warmed her fur as she dozed and I dug; I carved her a safe place while she protected me. I measured her length with the shovel’s long handle; she perked in amusement, and sniffed the heaped-up earth. Back down at the house, she seemed friskier, but gagged, eating. We called the vet a few days later. They were old friends. She held up a paw, and he injected a violet fluid. She swooned on the lawn; we watched her breathing quickly slow and cease. In a wheelbarrow up to the hole, her warm fur shone. Page 26 of 26