Chap. 9 Species invasions

advertisement

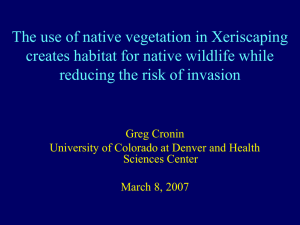

Species invasions 鄭先祐(Ayo) 台南大學 環境與生態學院 院長 Japalura@hotmail.com Contents What are the conservation implications of introduced species? What are the impacts of invasions? What factors determine whether a nonnative species becomes invasive? How are species introduced? How do we manage specie invasions? 2 Supplements Essay 9.1 maintaining an open mind on nonnative species Essay 9.2 Global exchange Box. 9.1 understanding the impacts of nonnative species Box 9.2 using models to improve control of introduced rabbits in Australia? 3 Supplements Case study 9.1 invaders in an invasible land: the case of the North American beaver in the Tierra Del Fuego- Cape Horn region of South America Case study 9.2 tracking aquatic invasive species Case study 9.3 When a beauty turns beast Case study 9.4 Biological control as a conservation tool 4 Introduction A carnivous snail exterminates over 56 endemic snail species in the southeast Pacific. A meter-long tree-climbing snake consumes endemic birds, bats, lizards and skinks on Guam. Aggressive ants and bees outcompete their native counterparts across the Americas. Smallpox decimates native human populations in North America. European rabbits in Australia. 5 We live in a world of introduced species. European trees live in Africa, African dung beetles in Australia, Australian possums in New Zealand, New Zealand snails in North America, North American in South America, South American trees in Asia, and Asian crabs in Europe. These emblematic and economically important species are introduced. 6 Four major conservation-focused questions 1. What are the impacts of introduced species? 2. What factors determine whether an invasion succeeds or fails? 3. How are species introduced? 4. How can we best control or even prevent invasions to reduce their conservation impacts? 7 Table 9.1 introduced species terminology Cryptogenic: applies to species whose status- native or nonnative – cannot readily be determined; commonly used for species whose cosmopolitan distributions or unclear taxonomy make their geographic origins uncertain. Indigenous: synonymous to native Introduced: refers to a species that has been released outside its native range; synonymous with nonnvative, nonindigenous. 8 Table 9.1 introduced species terminology Invasion: the establishment and spread of an introduced species. Invader: an introduced species. Native: describes species that evolved in a region. reintroduced: refers to intentionally released individuals of a native species that was locally endangered or extinct. 9 What are the conservation implications of introduced species? The scale of biological invasions is staggering (驚人巨大的). On the plains and prairies of North America 11% or plants are nonnative In Hawaii 35% are likewise nonnative. Approximately 8000 shrub and herb species and 750 tree species have been introduced to South Africa. Over 3000 plant species have been introduced to the state of California alone. 10 Worldwide, 20% of endangered vertebrate species are threatened by introduced species – 13% of those on mainlands and 31% on islands. Among freshwater fishes, 67% of tropical and over 50% of temperate introductions established successfully. A review of 31 fish introductions found that 77% caused native fish populations to decline. 11 Fig. 9.1 Accumulation of established estuarine and marine invaders in San Francisco Bay, California, over 140 years. 12 The rate of human-caused introductions exceeds background levels at an unprecedented scale (空前的規模). Species invasions affect economics, public health, and biodiversity. The estimated economic benefit of these marketable nonnative species runs to hundreds of billions of dollars per year in the US. 13 In the US, cost associated with the impacts and control of the Eurasian zebra mussel are estimated at $1 billion over the first 10 years of its invasion, European gypsy moth at $11million per year, European ship worms at $200 million per year, and purple loosestrife at $45 million per year – and these are only a few of the hundreds of unwanted species introduced world-wide. 14 Many public health threats are caused by introduced diseases. Smallpox, avian and human malaria, and the red tides caused by toxic phytoplankton can outbreak in new areas. The global epidemic of HIV/AIDS has spread around the world from its native Africa, claiming approximately 18 million victims to date, with 5 million new infections annually. 15 What are the impacts of introduced species? Invasion impacts can be evaluated across ecological and evolutionary realms. 1. Both direct and indirect effects of a single invader. 2. The consequences of multiple invasions. 3. The impacts across a range of ecological and evolutionary scales. 16 Population and community impacts Introduced predators The brown tree snake, Boiga irregularis, is a stunning example (頂好的範例) of the population and community level impacts of an introduced vertebrate predator on a naïve island population. The snake’s native range extends from Australia through New Guinea to the Solomon islands. Shortly after World War II, it arrived on the island of Guam where the only native snake was a tiny, wormlike insectivore. 17 The invader, the brown tree snake, Boiga irregularis The invader gradually spread across the island but remained at low densities for two decades until the early 1960s, when it began to appear in large numbers. More and more well-fed snakes were found in chicken coops; others were carbonized on power lines, causing electrical blackouts (Fig. 9.2). During this time, native birds began disappearing. Ten species of forest birds followed a similar pattern of decline. 18 19 關島鳥類衰減的原因? Pesticides, Avian diseases, introduction of competing birds, introduced predatory rats, cats, and other mammals. Today, the cumulative evidence indicates that the nocturnal brown tree snake, which can reach abundances up to 5,000/km2, has been largely responsible for eating the birds– now totaling 15 species– to extinction (Table 9.2) 20 Table 9.2 changes in vertebrate trophic interactions on Guam before 1945 and after the Brown tree snake invasion (1995) Carnivores (1945) Fairy tern Mangrove monitor Micronesian kingfisher Oceanic gecko Carnivores (1995) Brown tree snake Mangrove monitor 21 Table 9.2 changes in vertebrate trophic interactions on Guam before 1945 and after the Brown tree snake invasion (1995) Insectivores (1945) Pelagic (遠洋的)gecko Blue-tailed skink Mariana skink Spotted-belly gecko Mourning gecko House gecko Multilating gecko Moth skink Refous fantail Insectivores (1995) Blue-tailed skink Mourning gecko House gecko Multilating gecko Moth skink 22 Table 9.2 changes in vertebrate trophic interactions on Guam before 1945 and after the Brown tree snake invasion (1995) Omnivores (1945) Black rat Polynesian rat House mouse Guam Rail Mariana Crow Bridled white-eye Micronesian honeyeater Omnivores (1995) Black rat Polynesian rat House mouse 23 Table 9.2 changes in vertebrate trophic interactions on Guam before 1945 and after the Brown tree snake invasion (1995) Herbivores (1945) Micronesian starling Philippine turtledove Mariana fruit bat White-throated ground-dove Mariana fruit-dove Herbivores (1995) Philippine turtledove 24 Introduced competitors The impacts of competition are often trickier to observe and measure than those of predation. The most famous of the troublesome invaders is the Eurasian zebra mussel, which was first found in the Great Lakes in 1998 and has since spread into the St. Lawrence, Hudson, and Mississippi river drainages. In Lake Erie, Lake St. Clair, Lake Oneida, and the Detroit river, zebra mussels are estimated to have contributed to 64% -100% of local unionid extinctions, whereas habitat loss is estimated to have contributed to 2%-30%. 25 Fig. 9.4 Percent of native unionid mussels recently dead as a function of the relative wet weight of introduced European zebra mussels attached to their shells. 26 Morphological and behavioral impacts At smaller ecological scales, invaders can cause changes in the morphology and behavior of native species. 範例: 1. Predatory European green crab (Carcinus maenas) invaded the Northwest Atlantic coastline in the early to mid-1900s. 2. The Asian flowering plant Impatiens glandulifera was introduced to Europe from the Himalayas just over 100 years ago. 27 European green crab Populations of a small native herbivoreous intertidal snail (Littorina obtusata) developed a significantly thicker shell that provides some protection from predation. The snails responded to the crab’s chemical cues by growing thicker shells, and had a corresponding decrease in body mass. 而影 響其(snails)生殖力。 28 Asian flowering plant Impatiens glandulifera The nectar of I. glandulifera has a sugar content comparable to that of other bumblebee-pollinated plants, but its nectar production rate (0.47mg/hour per flower) is an order of magnitude greater than that of common native species (0.01-0.04 mg/hour) Pollinating bumblebees visit the invader approximately four times more frequently than they visit the native plants. Where the invader is established, visit to the native are reduced by 50% and its seed set by 25% (Fig. 9.7) 29 30 Genetic and evolutionary impacts At the genetic level, hybridization and introgression by introduced species can fundamentally alter native species fitness and generate new – and sometime aggressive– hybrids and strains. This process occurs in both animals and plants. In the North Pacific, a Mediterranean mussel appears to compete with its native congener directly and through hybridization. The introduced Mallard Duck threatens the persistence of the New Zealand Grey Duck, the endangered endemic Hawaiian Duck and the endemic Florida Mottled Duck by hybridizing with all three. In England, the introduced Atlantic cordgrass bybridized with the native European. 31 Ecosystem impacts Certain invaders have a disproportionate effect on ecosystem characteristics including habitat structure, disturbance regimes, and nutrient cycling. Codgrass salt marshes (composed primarily of Spartima spp.) are a major biological community type on the east coast of North America, where they are threatened by habitat loss. On the west coast, however, introduced populations of these species are flourishing as they spread across hundreds of square kilometers of tidal mud flats. 32 On the Atlantic coast, a major cause of habitat loss is grazing by nutria (coypu, Myocaster coypus, a large rodent), which was introduced from South America to develop fur farms in the 1930s. Released and escaped individuals established a feral population that spread quickly consuming already-threatened marsh habitat and increasing erosion. 33 What factors determine whether a nonnative species becomes invasive? Fig. 9.9 the invasion process. 34 Propagule (繁殖芽) pressure 所有的入侵者都需要有途徑(pathway),讓其可以 進入其原本分佈範圍之外的地區。 這些途徑(pathways)包含全球性的國際貿易,或 是地區性的道路興建,或是種植非本土的植物。 Propagule pressure = the quantity, quality, and frequency of arriving organisms. Propagule pressure is not a constant. As long as human trade and transport continue to grow and shift around the globe, invasion pathways will grow and shift as well. 35 Invading species characteristics We think are likely to make a species adaptable and fast-growing High fecundity Ability to spread vegetatively Parthenogenetic or hermaphroditic reproduction Broad physiological tolerances and diet 36 Reichard and Hamilton (1997) Classified 114 introduced species established in North America on the basis of their likelihood of spread. Using a statistical analysis, they ranked 11 traits in their ability to correctly classify theses species. Five of the traits contributed significantly to the likelihood of spread, and six were negatively associated. (Table 9.3) 37 Rejmannek and Richardson (1996) Classified 24 species of pine tree (Pinus spp.) introduced worldwide for cultivation. They found only three of ten life history characteristics contributed significantly to a Pinus species’ likelihood of successful invasion: short juvenile period, short interval between seed crops, and small seed mass. 38 Invaded community characteristics 1. The climate and habitat must be hospitable to potential invaders. 2. The species richness, interaction strengths, and trophic structure of the community, must be able to accommodate new species. Elton (1958) proposed the biotic resistance hypothesis that species-rich systems were more stable and therefore less susceptible to species outbreaks and invasions. 39 Disturbance (干擾) Disturbance – either natural or anthropogenic – may make a community more easily invadable, particularly for plants. The biotic resistance and disturbance hypotheses are complementary if we view them from the perspective of resource availability. A species-rich community with intense competition may be less invadable until disturbance alters the availability of resources, either by providing new resources, or by reducing the effectiveness of competitors, allowing an invader to establish (Fig. 9.14) 40 Fig. 9.14 A representation of the conceptual theory that increased resource availability increases a plant community’s 41 susceptibility to invasion. How do we mange species invasions? Controlling introduced species is not a simple prospect. The removal of an unwanted species may require physical control, chemical control, biological control. Some invaders are readily controlled by a single method, but more often several approaches are needed. 42 Species-based control For a conspicuous species, physical control alone may be effective. Physical control involves trapping, digging up, and otherwise removing invaders. For a more widespread invasion, chemical control may be more effective. An obvious drawback of chemical control is the nontarget mortality. Biological control is most highly developed in agricultural systems. In many cases, multiple approaches are required to target a particular invader. 43 Invasion prevention The precautionary principle, as a policy of guilty until proven innocent, or in terms of good lists and bad lists of low- and highrisk species. Preventing invasions requires identifying and regulating invasion pathways. Regardless of scale, effective invasion prevention requires a certain amount of legislation and policy development. 44 Table 9.5 timeline of US legislation relating to introduced species 1900 Lacey act, prohibits import of species that harm wildlife. 1912 Plant quarantine(檢疫) act, allows regulation and quarantine of nursery stock for plant diseases and insect pests. 1931 Animal damage control act, allows control of any animal that damages agriculture, aquaculture, public health, or other enterprise. 1939 Federal seed act, regulates import and transport of seeds, especially of noxious weeds. 1944 USDA organic act, allows federal eradication(消 滅) of plant pests, including noxious weeds. 1957 Federal plant pest act, prohibits import and transport of plant pests. 45 1974 Federal Noxious weeds act, regulates the transport of plants listed as noxious. 1977 President Carter’s Executive order 11987, Restricts federal agency introduction of nonnative species into “any natural ecosystem”. 1990 National aquatic nuisance prevention and control act, establishes voluntary (自願 性的) ballast water management guidelines. 1996 National invasive species act, establishes compulsory(強迫性的) ballast water management guidelines. 46 1999 President Clinton’s executive order 13112, establishes National invasive species council, with a mandate to develop a National invasive species management plan coordinating all federal on activity introduced species. 2000 Plant protection act, regulates plant pest transport, both accidental and intentional for biological control. 2001 National invasive species management plan, Mandated by Executive Order 13112, provides a blueprint for federal prevention management, research, and outreach on introduced species. 47 Case study 9.1: invaders in an invasible land. The case of the North America Beaver(河狸) (Castor canadensis) in the Tierral del Fuego-Cape Horn region of South America. 9.2: Tracking aquatic invasive species 9.3: When a beauty turns beast. Caulerpa taxifolia: one of the world’s worst invasive species. 9.4 Biological control as a conservation tool. 48 問題與討論 http://mail.nutn.edu.tw/~hycheng/ 49