Eliminative materialism

advertisement

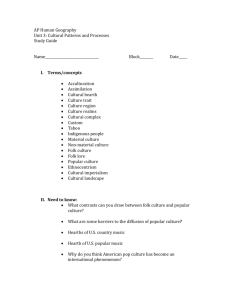

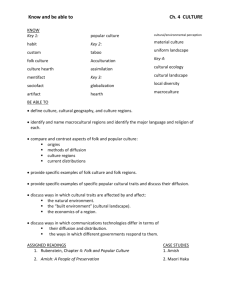

LECTURE FOUR ELIMINATIVE MATERIALISM 取消式唯物主义(或译为“消除式唯物主义”) SOME WORDS ON THE LAST LECTURE… I mentioned the term “supervenience” in the last lecture, and maybe not all of you have gotten the very idea of it. Don’t mind it now, I believe that we have other chances to talk it later. But this video may be related to this topic, although the title of the video is literally on the movie Inception. Here is the link for watching it on-line: http://v.youku.com/v_show/id_XMjE0NDM2NzA4.ht ml (The interview is in Chinese) THE FIRST APPROXIMATION TO ELIMINATIVE MATERIALISM (对取消式唯物主义 的权宜性表达) Eliminative materialism (or eliminativism 取消主义) is the radical claim that our ordinary, common-sense understanding of the mind is deeply wrong and that some or all of the mental states posited by common-sense do not actually exist. THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ELIMINATIVE MATERIALISM AND THE MIND/BRAIN IDENTITY THEORY (I) According to identity theory, we can legitimately talk about mind, but we need to keep the very fact in mind that any talk about metal states is just another way of talking about the corresponding brain states. Parallel to this case: it is fairly okay to talk about water, but you need to know that water is nothing but H2O. THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN ELIMINATIVE MATERIALISM AND THE MIND/BRAIN IDENTITY THEORY (II) According to eliminative materialism, we cannot legitimately talk about mind, and we need to keep the very fact in mind that any talk about the mental states is nonsense, and hence should be eliminated, rather than be reduced to another vocabulary (say, of the brain states). Parallel to these cases: it is wildly wrong to talk about Phlogiston (燃素) in modern chemistry or ether(以太is the term used to describe a medium for the propagation of light) in modern physics, since they do not exist at all. By the way, the Michelson–Morley experiment (麦克 尔逊—默雷实验) was performed in 1887 by Albert Michelson and Edward Morley in Cleveland, Ohio. Its results are generally considered to be the first strong evidence against the theory of ether. SO THE CONCLUSION IS: ELIMINATIVE MATERIALISM IS DEFINITELY MORE RADIAL THAN IDENTITY THEORY, INCLUDING TYPE-TO-TYPE IDENTITY THEROY AND TOKEN-TO-TOKEN THEORY. BUT WHAT DOES “RADICAL” MEAN IN THIS CONTEXT? How radical a species of materialism is, is measured in terms of how remote it is from dualism. In this sense, the token-to-token identity theory is the least radical one, the eliminative materialism is the most radical one, and the typeto-type materialism is something in the middle. There are other species of materialism which are weaker or less radical than eliminative materialism, but we will talk about them later. A COUPLE OF ELIMINATIVISTS IN CALIFORNIA (UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO , OR UCSD) Patricia Smith Paul Churchland (保尔· 邱 Churchland (帕琪夏娅· 邱 琪兰德, born Oct. 21, 琪兰德, born July 16, 1943, 1942, Canada) Canada) BUT THERE IS A PROBLEM FOR CHURCHLANDS: As we know, the target of eliminative materialism is our commonsensical account of mentality, which is expected to be eliminated. And the elimination of this sort is also supposed to be parallel to the elimination of phlogiston in chemistry. But our commonsensical account of mentality is not something like a theory of ether or a theory of Phlogiston, since they are typical scientific theories, whereas our common sense is just a loose talk. Did Churchlands choose a wrong target? THERE IS A CHEAP FIX FOR THIS PROBLEM: Just say that our commonsensical account of mentality suffices for a theory, i.e., FOLK PSYCHOLOGY (俗成心理学). Folk psychology is assumed to consist of both generalizations (or laws) and specific theoretical posits, denoted by our everyday psychological terms like ‘belief’ or ‘pain’. The generalizations are assumed to describe the various causal or counterfactual relations and regularities of the posits. For instance, a typical example of a folk psychological generalization would be: If someone has the desire for X and the belief that the best way to get X is by doing Y, then (barring certain conditions) that person will tend to do Y. If I have the desire for water and the belief that the best way to get water is to buy a bottle of water from the super market, then (barring certain conditions) I will tend to buy a bottle of water in a supermarket. THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FOLK PSYCHOLOGY AND BEHAVIORISM Both tend to generalize what an agent would regularly do when a mental process is going on in his mind, but behaviorists tend to say something more: The behavioral generalizations can replace our talk about mentality; While folk psychologists would say: The behavioral generalizations are still about mentality. We still need to keep our mental vocabulary in our philosophical dictionary. BUT WHY? Because for folk psychologists, there are something special about our beliefs. First, there are various causal properties concerning beliefs. Beliefs are the sort of states that are caused in certain specific circumstances, interact with other cognitive states in various ways, and come to generate various sorts of behavior, depending on the agent's other desires and mental states. Second, beliefs have intentionality(意向性); that is, they each express a proposition or are about a particular state of affairs. This inherent intentionality (also called “meaning”, “content”, and “semantic character”语义学特征), is commonly regarded as something special about beliefs and other propositional attitudes. AND WHY FOLK PSYCHOLOGY IS WRONG, ACCORDING TO ELIMINATIVISM? Eliminative materialists argue that the central tenets of folk psychology radically misdescribe cognitive processes; consequently, the posits of folk psychology pick out nothing that is real. Like dualists, eliminative materialists insist that ordinary mental states can not in any way be reduced to or identified with neurological events or processes. However, unlike dualists, eliminativists claim there is nothing more to the mind than what occurs in the brain. The reason mental states are irreducible is not because they are non-physical; rather, it is because mental states, as described by common-sense psychology, do not really exist. ARGUMENT NO.1 Patricia and Paul Churchland have offered a number of arguments based on general considerations about theory evaluation. For example, they have argued that any promising and accurate theory should offer a fertile research program (能 带 来成 果的 研 究规 划 ) with considerable explanatory power(足够大的解释力). They note, however, that common-sense psychology appears to be stagnant, and there is a broad range of mental phenomena that folk psychology does not allow us to explain. Questions about why we dream, various aspects of mental illness, consciousness, memory and learning are completely ignored by folk psychology. According to the Churchlands, these considerations indicate that folk psychology may be in much worse shape than we commonly recognize. ARGUMENT NO.2 Another argument that appeals to general theoretical considerations offers an inductive inference(归纳推理) based on the past record of folk theories. Folk physics, folk biology and the like all proved to be radically mistaken. Since folk theories generally turn out to be mistaken, it seems quite improbable that folk psychology will turn out true. Indeed, since folk psychology concerns a subject that is far more complex and difficult than any past folk theory, it seems wildly implausible that this one time we actually got things right. ARGUMENT NO.3 (I) There is a problem with propositional attitudes (命题态度). propositional attitudes appear to have a form similar to public language sentences, with a compositional structure and syntax. For example, a person‘s belief that, say, the president dislikes terrorists appears to be composed of the concepts “THE PRESIDENT”, “DISLIKES”, and “TERRORISTS”. A belief-structure mirrors the sentence-structure. By the way, beliefs resemble public sentences in that they have semantic properties. ARGUMENT NO.3 (II) Some writers have emphasized the apparent mismatch between the sentential structure of propositional attitudes on the one hand, and the actual neurological structures of the brain on the other hand. Whereas the former involves discrete symbols (离散符号) and a combinatorial syntax (组合句法), the latter involves action potentials (动作电位), spiking frequencies (脉冲频) and spreading activation (激活扩散). As Patricia Churchland (1986) has argued, it is hard to see where in the brain we are going to find anything that even remotely resembles the sentence-like structure that appears to be essential to beliefs and other propositional attitudes. A CASE STUDY OF PAIN OFFERED BY DANIEL DENNETT Daniel Clement Dennett (born March 28, 1942)[1][2] is an American philosopher, writer and cognitive scientist whose research centers on thephilosophy of mind, philosophy of science and philosophy of biology, particularly as those fields relate to evolutionary biology and cognitive science.[3] He is currently the Codirector of the Center for Cognitive Studies, the Austin B. Fletcher Professor of Philosophy, and a University Professor at Tufts University. FOR CHINSE READERS: 原作名: Consciousness Explained 作者: 丹尼尔·丹尼特 译者: 苏德超 / 李涤 非 / 陈虎平 出版社: 北京理工大学 出版社 出版年: 2008-9-1 页数: 598 定价: 39.00元 装帧: 平装 丛书: 盗火者译丛 ISBN: 9787564009618 HOW TO PHILOSOPHICAL ANALYZE PAIN? It may be claimed for the sake of folk psychology that we need to keep “pain” in our psychological vocabulary, given that my feeling of my pain is always infallible and awful. By contrast, Daniel Dennett (1978) has argued that our concept of pain is fundamentally flawed. In certain conditions, drugs like morphine (吗啡) cause subjects (被试) to report that they are experiencing excruciating pain, but that it is not unpleasant. It seems we are either wrong to think that people cannot be mistaken about being in pain (wrong about infallibility), or pain needn't be inherently awful (wrong about intrinsic awfulness). Dennett suggests that part of the reason we may have difficulty replicating pain in computational systems is because our concept is so defective that it picks out nothing real. ARGUMENTS AGAINST ELIMITIVISM Many writers have argued that eliminative materialism is in some sense self-refuting(自相矛 盾). If eliminative materialism to be asserted as a thesis, the eliminativist herself must believe that it is true. But if the eliminativist has such a belief, then there are beliefs and eliminativism is thereby proven false. Reply: the objection begs the question by assuming that eliminativists do have beliefs about eliminativism. But they would say: we, like any other one, do not genuinely possess any belief. Our belief in eliminativism should be formulated on a level higher than that of the public language. By the way, paradoxes of this sort are not novel in the history. Think about the Liar Paradox. “This sentence is false." If the quoted sentence is true, then false, vice versa. ARGUMENTS AGAINST ELIMITIVISM Philosophers influenced by the writings of Wittgenstein (1953) and Ryle (1949) will insist that (contra many eliminativists) folk psychology is not a quasi-scientific theory used to explain or predict behavior, nor does it treat mental states like beliefs as discrete inner causes of behavior (Bogdan, 1991; Haldane, 1988; Hannan, 1993; Wilkes, 1993). What folk psychology actually does treat beliefs and desires as is much less clear in this tradition. One perspective (Dennett, 1987) is that propositional attitudes are actually dispositional states that we use to adopt a certain heuristic stance toward rational agents. FURTHER READINGS: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/materialismeliminative/#FolPsyTheThe Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes Paul M. Churchland The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 78, No. 2. (Feb., 1981), pp. 67-90. (YOU CAN FIND THE PDF OF THE PAPER IN THE PUBLIC E-MAIL BOX) SOME WORDS ON THE FINAL EXAM I will evaluate every student by doing two things. First, I will evaluate everybody’s writing skills. That means, you need to submit a paper to me before the end of this semester, hopefully just before the final exam. The topic should be on any topic that I have discussed in the class, or that is covered by Prof. Searle’ book. It should be written in English, no matter whether you are a native speaker of English or not. The paper is expected to be composed of 3,500 words or above. And you are expected to write it by using Microsoft Word. I need not only the Hard Copies, but also the electronic versions, which are expected to send to my e-mail box before the final exam. Second, a final exam is indispensible, by which your comprehensive understanding of different topics in philosophy of mind will be evaluated. Chinese students should write in Chinese in the final exam, while native speakers of English can use English. SOME MORE WORDS ON THE PAPER-WRITING The paper should be written in accordance with the so-called Chicago-style(芝加哥文体), and double-spaced(间距两行). Anybody who wants to know what Chicago-style is, please read the following link: http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citatio nguide.html More importantly, the paper should be written in the analytical way. You need to formulate a thesis, defend it by explicit arguments, and evaluate its potential rival positions. Both an abstract and a bibliography are required. CAVEATS!! Don’t use British English! Don’t get sentences more complicated than necessary! Please follow the pattern of Searle’s writing! If you are a native speaker of Chinese, just try to express what you want to say directly in English! Please don’t write it in Chinese first, then translate it into English! A HOW-TO MANUAL 1. You need to find a topic that can really interest you. You need to have motivations which are strong enough to propel your research! That means, you need find fun in it! 2. Read the corresponding entry on the Stanford Encyclopedia Dictionary, so you will know the literature related to the topic. http://plato.stanford.edu/contents.html 3. Read the most cited papers on the topic, and find the most favorable position among all of the possible ones. Please also pay attention to this resource, which is extremely useful: http://consc.net/ 4. Try to explicate your thesis in a sentence. It cannot be too long. 5. Try to argue for it, and tell the audience how the thesis can survive critics’ criticisms. 6. If you have any problems in your research, please don’t hesitate to write to me. xuyingjinstone@sina.com THE END ENJOY YOUR SHORT-TERM VOCATION OF QINGMING! 清明节快乐!