Fauzia Shariff

advertisement

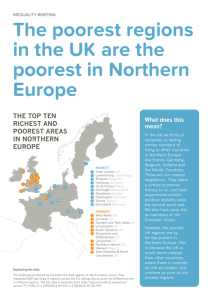

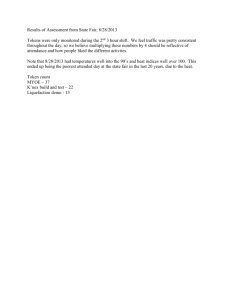

Rights Based Approach to Implementing Social Transfers: Some Issues for Discussion Fauzia Shariff Reaching the Very Poorest, Policy Division 22nd June 2005 This does not represent DFID policy 1 Palace Street, London SW1E 5HE Abercrombie House, Eaglesham Road, East Kilbride, Glasgow G75 8EA DFID’s Policy Commitments on Rights • The government’s White Papers of 1997 and 2000 note the government’s commitment to human rights. DFID’s Target Strategy Paper on Human Rights sets out key priorities for addressing human rights issues as part of our overall approach to development. • Key issues: • Participation of poor people in decision making • Building socially inclusive societies by addressing exclusion, discrimination and inequality • Supporting governments who take rights seriously and encouraging others to do so. Page 1 Social Protection and Rights In context of social protection DFID is increasingly interested in social transfers • • Challenges in Africa: need effective responses to predictable humanitarian crises to allow beneficiaries to build assets and prepare for future crisis’ • Creates entitlements rather than handouts and helps to change view of poorest • Complement health and education initiatives – poorest regular, predictable income to feed and house children and have choice (education rather than work) • Empowers poorest to manage their own lives improves human development outcomes – key to long-term poverty reduction Page 2 What are social transfers? • Regular and predictable grants – usually in the form of cash – that are provided to vulnerable households or individuals. • Examples • Non-contributory pensions • Family allowances • Disability allowances • Widow’s allowance • Conditional cash transfers (e.g. to households with children to provide cash on condition that children attend school and health clinics) • Work Programmes providing cash or food to the unemployed in exchange for work Page 3 Some rights they protect • • • Right to social security (UDHR art. 22) Right to just and favourable remuneration ensuring an existence worthy of human dignity and supplemented by other means of social protection (UDHR art. 23.3) Right to standard of living adequate for health and well-being including food, clothing, housing and medical care, necessary social services, the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood - motherhood and childhood are entitled to special care and assistance. (UDHR art. 25) These are linked to the enjoyment of other rights related to health and education. Page 4 Some Challenges in a Rights Approach to Implementing Social Transfers 1. Participation of poorest and enforceability by the poor 2. Inclusion of poorest 3. Country-led approaches to development Page 5 1. Participation and Enforceability a/ Participation • Providing transfers in cash instead of food etc. Beneficiaries make decision on how to allocate benefits – studies show they are likely to spend on greater variety of food, paying off debts, investing in livestock and animal husbandry etc. Getting recipients’ perspectives on policy before and during (e.g. participatory evaluation of projects) • ☢ Takes time, issues of representation, data becomes out of date ☢ Create expectations, and worsen relations with state ☢ Getting unbiased feedback on impact of transfers on children and on gender inequalities in HH can be difficult • Having an impact on setting the agenda at national policy level ☢ Excluded groups often little representation in government Page 6 b/ Enforceability Clarity of Entitlements • Clarity of rights set out in policy/legislation and commitment to enforce Knowledge and Information • Knowledge of how system works – recipients and Implementing officers • Information on who should get what, when – is it acceptable to put beneficiaries’ names on display? ☢ Access issues: Illiteracy, linguistic diversity, physical remoteness, poor transport and social isolation Means of Enforcing What is Due • Vertical accountability: Government-citizen Civil society, courts/administrative appeals system, community mobilisation ☢ Access to justice (formal/informal), freedom of expression and association, transparency of appeal system • • Horizontal accountability: transparency vs culture of corruption Page 7 • • Right: Children Underweight (% severe) by quintile in 1996 and 2000 (above) and annual rate of improvement of each quintile relative to the national average (below) 15 10 5 0 Lowest Second Middle Fourth Highest 20 15 10 5 0 -5 -10 Highest • 2000 20 Fourth • In Tanzania, households with disabled members are 20% more likely to be living in poverty. Women account for nearly 70% of the 1.2 billion people currently living in extreme poverty. In Brazil, nearly three times as many black women as white women die from the complications of pregnancy and childbirth. In the Indian states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, primary school enrolment for scheduled caste and scheduled tribe girls is 37%, compared with 60% for girls from non-scheduled castes. Among boys from non-scheduled castes, 77% are enrolled. In China, although ethnic minorities make up less than 9% of the population, they account for 37% of known cases of HIV. 1996 Middle • 25 Second Excluded benefit least from development 30 Lowest 2. Inclusion -15 Page 8 Targeting Social transfers target the poorest and excluded groups ☢ Who benefits? Who chooses • Universal vs Targeted – Equality of process or of outcome Equal payments to all children, or targeted payments to the poorest children. • Community Based targeting • Reinforcing community level distribution of wealth and power? • Providing real say for poorest in local community context Page 9 3. Country-led Approach to Social Transfers Country ownership means governments have to take initiative in adopting SP programmes. • Getting SP on the agenda - Governments are most likely to respond to interests of citizens with a stronger voice – not the interests of the poorest and excluded groups – unless they perceive benefits from stronger citizenship ties, (e.g. election time, in response to social unrest in deprived areas) • Once in place social transfers integrate poor people (end exploitative relationships of work or debt) and may make people more engaged with state, more politically aware • But they also create ‘entitlements’ with obligations on State - may resist obligations to deliver benefits seen as inducing dependence, and potential shift in power to poor that might result • (potentially) donor - may mean longer predictable aid flows which can clash with budgetary flows of donors • Page 10 References For more information see: Human Rights Target Strategy Paper: http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/tsphuman.pdf Human Rights Review: http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/humrightsrevfull.pdf Partnerships for Poverty Reduction http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/conditionality.pdf Eliminating Hunger: Target Strategy Paper http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/elimhunger.pdf Safety, Security and Access to Justice http://www.dfid.gov.uk/pubs/files/safesecureaccjustice .pdf 1 Palace Street, London SW1E 5HE Abercrombie House, Eaglesham Road, East Kilbride, Glasgow G75 8EA Page 11