Strategic Writing PowerPoint [10/16/2014]

advertisement

![Strategic Writing PowerPoint [10/16/2014]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010025510_1-8534370caacce4d414a09eadd26fbce4-768x994.png)

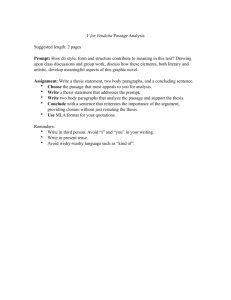

• What is history? • What types of writing have you done in your history classes? • What does it mean to write history “as a historian”? 1. What do you notice about this document? 2. What type of document is this? 3. Why was this document produced? 4. What went into producing this document? • • • • • • Consider a historical question or problem Research and sift through the available sources Draw inferences and conclusions to create a thesis Organize information and evidence Writing, feedback, revision, and editing Complete and submit the work Question: Which step is the most critical? • Why do historians write? • What might be some reasons for writing in history classes? • What are the purposes for different types of writing? • What is the audience’s role in historical writing? • What is a prompt? • The importance of addressing the prompt • TAP: Topic, Audience, Purpose • Prompt Analysis—Practice • Common terms found in prompts: • Read as a “historical detective” to gather evidence in response to a question or prompt (putting the pieces of the puzzle together) • Sourcing • Contextualizing • Corroborating • SOAPS: Speaker, Occasion, Audience, Purpose, Significance • 5W’s plus S: – Who? (the source, including point of view and bias) – What? (the type of document and its key ideas) – Where? (context) – When? (context) – Why? (purpose of the document’s creation) – So what? (significance) • Organize information and sources into categories: – SPRITE: Social, Political, Religious, Intellectual, Technological, Economic – Subcategories such as causes, effects, women, military, etc. • Categories should relate directly to the thesis • Categories provide the focus for body paragraphs • A single document may fall into multiple categories • • • • Why are maps created? Create a plan or road map for writing Make sure you have enough information to begin writing Various formats of organization: – Outlining – Categorizing and classifying charts (a column for each body paragraph, with info under each column) – Two-column charts (pro vs. con, or interpretation and evidence) • The main idea or argument that you will support and defend with evidence • Sets up the plan for the whole paper and directly relates to the prompt or historical question • Supported by key points, categories, or topics in your introduction as a preview of the body paragraphs • Sample thesis statements: – “The social, political, and economic ideals stated by the Declaration of Independence have not been satisfactorily realized in contemporary America.” – “The Protestant Reformation was surely sparked by the abuses of the Catholic Church, but it was fueled by the passion of reformers like Luther, Zwingli, and Calvin.” • Set-up and packaging for a thesis statement • Historical background/context: – “The Civil War between the United States and the Confederate States of America took place between 1861 and 1865 across thousands of battlefields.” – “The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw unparalleled political changes throughout the world.” • Catch a reader’s attention so they want to read further – “Those who oppose immigration to America are unAmerican, unless of course they are Native Americans.” – “At many times and in many places, the stomach has prevailed over the mind when it comes to political choices.” • Topic sentence: The first sentence of a paragraph, which sets out the main idea • The topic sentence should directly link to the thesis • Subsequent sentences should directly link to the topic sentence’s main idea • The language used should reflect the type of thinking required by the prompt • Example: What were the causes of World War I? – “One of the causes of World War I was militarism.” – “World War I was the result of years of military buildup.” Like a lawyer, you must prove your case with evidence: • Your evidence should link to your topic sentence, as well as to the thesis • Use clear, convincing quotes and facts from multiple primary or statistical sources—at least two per paragraph • Avoid saying, “Document A says x”; weave in quotes instead • Example 1: John Brown’s naiveté is brought out by statements such as “I never did intend murder…” • Example 2: The “right of the people to keep and bear arms” meant something completely different in 1787, due to the socio-political context in which it was written • The explanation (also called commentary or analysis) helps the reader understand exactly why and how your evidence supports your thesis and topic sentence – Should interpret the evidence and also answer the question, “So what?” – May require multiple sentences • Basic example: Bob was seen at a soccer game by four different individuals at 2 pm (evidence). Therefore, he could not have robbed the store at 2 pm (explanation). • Historical example: In saying that “a house divided against itself cannot stand,” Lincoln argued that slavery and the divisions it produced could not go on indefinitely. • The concluding sentence should reconnect the reader to the idea expressed in the topic sentence and thesis • The concluding sentence should not merely restate the topic sentence • The conclusion provides the final opportunity to make your point to your audience • Do not merely repeat your introduction and thesis, but instead think about what lessons should be learned from this event, or its relevance to today • Write something which will stand out to your audience—a memorable quote, or a restatement of the thesis that brings out the “So what?” of your main argument • Reflect and read • Rubric: How well does the writing meet the criteria? • Word choice: Avoid “I,” “in my opinion,” “obviously,” “you,” clichés, and slang • Citation: Has proper attribution been given? Has proper formatting been used? • Clarity: Would someone who does not know about history understand what is being said? • What are your stronger points? How do you know? • What do you need to work on? How do you know? • How do you plan to improve?