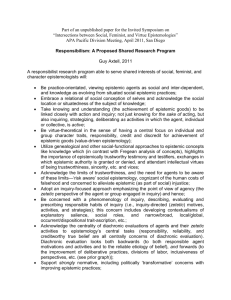

epistemic

I’m Glad

You Enjoyed My Talk!

Lorenzo Casini

L.Casini@kent.ac.uk

Value freedom: Is it possible? Is it desirable?

Week 4

Phil 152

Winter 2010

Where values might play a role in science

1. In the ‘ early stages ’ (Douglas’s term): In the set-up and conduct of science.

2. In standards of acceptance for knowledge claims.

3. In the effects of science

.

Three types of values to consider

• Epistemic – those conducive to truth.

• ‘ Cognitive ’ – characteristics other than truth one might want of a scientific practice or result.

Simplicity, intersubjectively agreed on, fruitfulness, mutuality of interaction, ontological parsimony (Ockham’s razor), ontological heterogeneity…

• ‘ Moral ’ – ethical, political, cultural, economic...

Douglas: direct & indirect roles

• Direct role: “…values determine our decisions in and of themselves acting as stand alone reasons to motivate our choices. They do this by placing value on some intended option or outcome, whether it is to valorize the choice or condemn it.”

– NC: surely the italicized word is too strong since it doesn’t allow for combinations of reasons.

• Indirect role: when “evidence or reasons…are incomplete…and thus there is uncertainty. Then values serve a crucial role of helping us determine whether the evidence available is sufficient for the choice and what the importance of uncertainty is…”

– NC: better, indirect = ¬direct.

1. Legitimate locales for direct roles for moral values: early stages?

Douglas argues that in the early stages moral

(and ‘cognitive’) values can – indeed, should – be invoked as independent reasons (i.e. direct role) in social or individual decisions about

• What projects to undertake.

• How much to invest.

• What questions to ask.

• Aspects of methodology.

But beware

• “ One cannot use values to direct the selection of a problem and a formulation of a methodology that in combination predetermines (or substantially restricts) the outcomes of a study. Such an approach undermines the core value of science, to produce reliable knowledge…”

• Who decides, and how?

Example

• A JAMA study suggests RCTs conducted by pharmaceuticals of their products get positive results more often than ones conducted by independent experimenters.

• Suspicion – careful choice of question and method to increase chance of positive results, e.g.

– Choice of exact effect measured

– Choice of control

– …

• Choice of problems to study, how much to invest, etc. may be a well-known and uncontroversial place for moral and political values to enter, but that’s no reason to diminish the importance or ignore the problems.

• Philip Kitcher on well-ordered science:

Science should use proper methods to pursue the informed democratically chosen aims of humanity.

(See Science,Truth, and Democracy)

• Here is a case in point…(See J Reiss and P Kitcher,

‘Neglected Diseases and Well-ordered Science’,

CPNSS, 2008)

Global Health Inequalities

The global disease burden is distributed very unequally:

Between first- and third-world countries:

Only 10% of the world population live in Africa but 40% of deaths due to communicable diseases occur there (many of which are preventable).

Between men and women:

Almost every disease kills more women than men despite the fact that men slightly outnumber women (exception: cancer; men are much more likely to die of injuries).

Within developing countries, between rich and poor:

Chagas is caused by a parasite that lives in cracks and holes of substandard housing of the rural poor.

River blindness is caused by a fly that breeds in fast-flowing rivers and streams and, too, affects the rural poor.

Is BMR well-ordered?

Biomedical research as practiced today is very far from this ideal.

•

Of the 1393 drugs that were licensed between 1975 and 1997 only 13 aimed at treating tropical diseases.

•

Of the over $100 bn spent on biomedical research globally per year (2003: $125.8 bn), only a tiny fraction goes into investigating diseases of the poor.

•

Malaria, pneumonia, diarrhoea and tb account for

21% of the global disease burden (in terms of DALYs lost) but receive only 0.31% of funding.

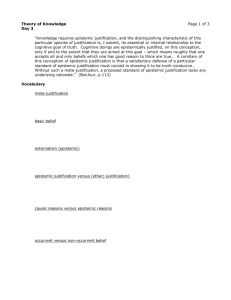

Condition

Is BMR well-ordered?

GDB (Million

DALYs)

% of total GDB R&D funding (Mill.

US$)

R&D funding per

DALY (US$)

All 1,470

HIV/AIDS + TB +

Malaria

167

100

11.4

105,900

1,400

72

8.4

CVD

Malaria

Diabetes

TB

148.19

46.49

16.19

34.74

9.9

3.1

1.1

2.3

Data for 2001 (source: Global Forum for Health Research Report 2006, 90)

9,402

288

1,653

378

63.45

6.2

102.07

10.88

2. Legitimate locales for direct role for moral values: standards for acceptance?

Two different reasons:

• To fill in since scientific method is insufficient to fix scientific claims in either the social or natural sciences.

• To set levels of uncertainty for accepting scientific results. (This is Douglas’s issue.)

2.1 Filling in

Surely we don’t want to use our moral values to settle what we think is true, or what we will use in technology and policy.

But many think

• It’s inevitable. (See SSK and feminist literature for lots of examples.)

• We need something to fill in.

The problem in outline

• Scientific claims ‘go beyond’ what is already established. Policy predictions too.

• How?

– Problem of underdetermination: The known facts always underdetermine the hypothesis/ There’s always more than one hypothesis compatible with the known facts.

• Something else must fill in.

• Should values do the job?

– Epistemic values

– Other values

Filling in: epistemic values

• Given that the known facts (indeed, generally ‘all possible’ ‘observations’) underdetermine the hypotheses we care about, what fills in?

• Answer: epistemic values.

Accuracy, consistency, broad scope, simplicity, fruitfulness, external consistency, unifying power, explaining known facts, explaining different kinds of facts, explaining why rivals are successful, capturing rivals as limiting cases, novelty, ontological heterogeneity, mutuality of interaction, applicability to human needs (‘pragmatic’), diffusion of power

(‘pragmatic’).

Filling in: Is Douglas too optimistic?

Douglas:

• We should use only truly epistemic values because the core value of science is ‘reliable knowledge’.

• James Gaa’s ‘moral autonomy’: “acceptance

(and rejection) decisions ought to be made with regard only to the attainment of the characteristic (‘purely epistemic’) goals of science.”

Troubles for epistemic values

• Who decides what they are?

• They are too vague to provide answers.

• They often conflict and there is no natural order.

• Why think they are epistemic?

• Why privilege them if we can’t show they are epistemic?

Are epistemic values epistemic?

• E McMullin: “Such characteristic values I will call epistemic, because they are presumed to promote the truth-like character of science …”

Note1: ‘presumed’ which lets in Newton’s theological argumentation. Still, McMullin defends the claim that they do promote truth.

Note 2: ‘truth-like’ – in view of scientific revolutions I take it.

• L Laudan: “If these attributes….are virtues, and I believe they are, they are not epistemic virtues .”

• A Wylie, more neutrally: Objectivity = “…a loosely defined family of epistemic virtues that we expect will be maximized, in some combination, by the claims we authorize as knowledge .”

• We do not want non-epistemic values to influence what claims we accept in social and natural science.

• Problem: We are like sailors rebuilding our ships at sea (Otto Neurath). All our knowledge and methods are socially and historically conditioned. This makes the influence of values to be both likely and unrecognized.

• Examples of your own please.

• Conventional solution: critical, thoughtful, informed intersubjective debate.

– And keep at it.

2.2 Setting levels of uncertainty

• Douglas says value judgments are necessary here.

(Her ‘indirect role’.)

• But ‘pure science’ doesn’t know where it will be used.

– R Jeffrey: Don’t accept or reject, set probability.

– R Rudner: We must then accept or reject the probability assignment.

Study question: do Rudner’s first set of considerations still work at this iteration?

– Difficulties because decisions are embedded: see

Douglas example of deciding if data points are correct.

Setting levels of uncertainty

• Canonical solution: make scientific claims very precise .

– The standards and methods of test become part of the statement of the result.

– Cf. later in study of evidence-based policy:

‘efficacy’ is defined as a certain kind of result in an

RCT, not as ‘having the power to bring about an effect’.

• This eases the problem but makes big troubles for users.

The effects of science

• We think of the atom bomb, penicillin, lasers for eye operations, discrimination against those genetically predisposed to disease, artificial limbs, the steam engine…

• Don’t forget the ‘self-fulfilling’ effects of counting and classifying .

– See M Foucault, I Hacking, T Porter,…

– Examples

• Refugee women

• Jews

• Homosexuals

• …

3.

The effects of science

Three views

– Learning truth trumps all (or, within bounds of acceptable methods of search).

– Kitcher: science – and scientists – have a

(defeasible) obligation not to create knowledge that will predictably be misused.

Possible examples: DNA and genetic diseases

– Everything is so unpredictable that this obligation can generally be ignored.