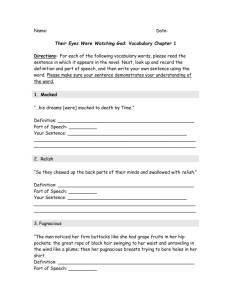

Their Eyes Were Watching God

advertisement

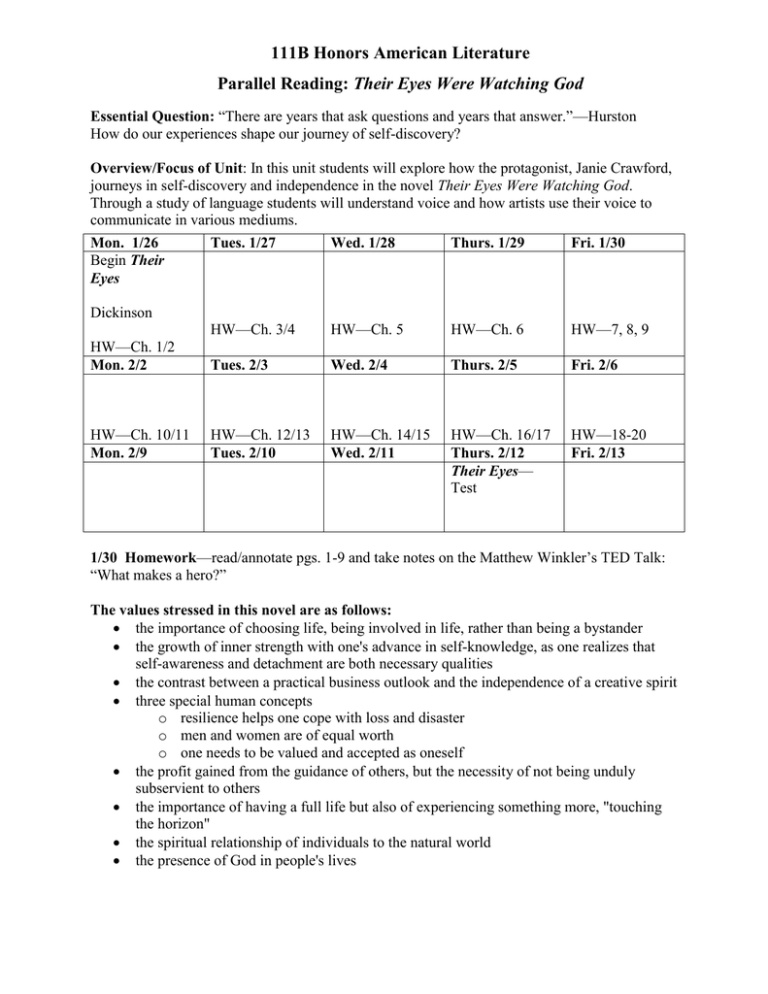

111B Honors American Literature Parallel Reading: Their Eyes Were Watching God Essential Question: “There are years that ask questions and years that answer.”—Hurston How do our experiences shape our journey of self-discovery? Overview/Focus of Unit: In this unit students will explore how the protagonist, Janie Crawford, journeys in self-discovery and independence in the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. Through a study of language students will understand voice and how artists use their voice to communicate in various mediums. Mon. 1/26 Begin Their Eyes Tues. 1/27 Wed. 1/28 Thurs. 1/29 Fri. 1/30 HW—Ch. 3/4 HW—Ch. 5 HW—Ch. 6 HW—7, 8, 9 HW—Ch. 1/2 Mon. 2/2 Tues. 2/3 Wed. 2/4 Thurs. 2/5 Fri. 2/6 HW—Ch. 10/11 Mon. 2/9 HW—Ch. 12/13 Tues. 2/10 HW—Ch. 14/15 Wed. 2/11 HW—Ch. 16/17 Thurs. 2/12 Their Eyes— Test HW—18-20 Fri. 2/13 Dickinson 1/30 Homework—read/annotate pgs. 1-9 and take notes on the Matthew Winkler’s TED Talk: “What makes a hero?” The values stressed in this novel are as follows: the importance of choosing life, being involved in life, rather than being a bystander the growth of inner strength with one's advance in self-knowledge, as one realizes that self-awareness and detachment are both necessary qualities the contrast between a practical business outlook and the independence of a creative spirit three special human concepts o resilience helps one cope with loss and disaster o men and women are of equal worth o one needs to be valued and accepted as oneself the profit gained from the guidance of others, but the necessity of not being unduly subservient to others the importance of having a full life but also of experiencing something more, "touching the horizon" the spiritual relationship of individuals to the natural world the presence of God in people's lives The bildungsroman (novel of education) is a type of novel originating in Germany which presents the development of a character mostly from childhood to maturity. This process typically contains conflicts and struggles, which are ideally overcome in the end so that the protagonist can become a valid and valuable member of society. The term bildungsroman denotes a novel of all-around self-development. 1. A bildungsroman is, most generally, the story of a single individual's moral, psychological, and intellectual development within the context of a defined social order. The growth process, at its roots a quest story, has been described as both "an apprenticeship to life" and a "search for meaningful existence within society." 2. To spur the hero or heroine on to their journey, some form of loss or discontent must jar them at an early stage away from the home or family setting. 3. The process of maturity is long, arduous, and gradual, consisting of repeated clashes between the protagonist's needs and desires and the views and judgments enforced by an unbending social order. 4. Growth usually results in alienation from traditional roles imposed by family, church and other social institutions at an early age; often the protagonist has suffered loss at a young age and must search for identity. 5. Eventually, the spirit and values of the social order become manifest in the protagonist, who is then accommodated into society. The novel ends with an assessment by the protagonist of himself and his new place in that society. The Heroic Pattern: Archetypal Elements and Events Element 1: Early Life The hero’s mother is a royal virgin His father is a king The circumstances of his conception and birth are unusual, and He is reputed to be the son of a god At birth an attempt is made, often by his father or maternal grandfather, to kill him, but He is spirited away, and He is reared by foster parents in a far country Element 2: Young Adulthood On reaching manhood, he returns or goes to his future kingdom. He falls under the control of an enemy. He often makes a journey to the Underworld, or the shapes of the dead may visit him. Element 3: Journey or Quest Has a purpose for his journey Travels to the end of the earth Seeks directions and/or advice Finds women a danger to his success Gains a guide Is given weapons or talismans with magical powers Crosses water Confronts the powers of death in the form of shapes and/or monsters Tries to bring back to earth an item or person from the Underworld, but Is at best only partly successful. Element 4: The Return Home After victory over the king and/or a giant, dragon, or wild beast He marries a princess, often the daughter of his predecessor, and becomes king. Eventually, he loses favor with the gods and/or his subjects, and He meets a mysterious death. His children do not succeed him. His body is not buried, but He has one or more holy sepulchers. Element 5: Major Themes often associated with the hero The human quest: a journey of discovery about himself, his society, and his universe Isolation: essentially alone, the hero’s courage, strength, and wisdom are tested The quest as a dual struggle, both physical and psychological (a struggle to resolve the conflict between the body and the soul, between duty and desire, between the animal urges and divine aspirations, etc.) The cycle of life, death, and rebirth The hero as redeemer: often restores the kingdom to health and fertility The hero as model: "by his half-divine nature, his glorious deeds, his relentless pursuit of immortality, the hero uplifts humanity from its dismal condition and reminds us of our godlike potential" (Powell 230) The hero as protector of civilization: kills beasts and other enemies that threaten the kingdom; adds to the fund of knowledge The dual nature of man: intellect/wisdom versus savagery/violence/ambition/primal urges Harris, Stephen L. and Gloria Platner, Classical Mythology: Images and Insights, 2nd. Mayfield Publishing Company. Mountain View, California: London: Toronto. 1998. Powell, Barry B. Greek Myth, 4th. Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River, NJ. 2001. How It Feels to Be Colored Me –by Zora Neal Hurston I AM COLORED but I offer nothing in the way of extenuating circumstances except the fact that I am the only Negro in the United States whose grandfather on the mother's side was not an Indian chief. I remember the very day that I became colored. Up to my thirteenth year I lived in the little Negro town of Eatonville, Florida. It is exclusively a colored town. The only white people I knew passed through the town going to or coming from Orlando. The native whites rode dusty horses, the Northern tourists chugged down the sandy village road in automobiles. The town knew the Southerners and never stopped cane chewing when they passed. But the Northerners were something else again. They were peered at cautiously from behind curtains by the timid. The more venturesome would come out on the porch to watch them go past and got just as much pleasure out of the tourists as the tourists got out of the village. The front porch might seem a daring place for the rest of the town, but it was a gallery seat for me. My favorite place was atop the gate-post. Proscenium box for a born first-nighter. Not only did I enjoy the show, but I didn't mind the actors knowing that I liked it. I usually spoke to them in passing. I'd wave at them and when they returned my salute, I would say something like this: "Howdy-do-well-I-thank-you-where-yougoin'?" Usually automobile or the horse paused at this, and after a queer exchange of compliments, I would probably "go a piece of the way" with them, as we say in farthest Florida. If one of my family happened to come to the front in time to see me, of course negotiations would be rudely broken off. But even so, it is clear that I was the first "welcome-to-ourstate" Floridian, and I hope the Miami Chamber of Commerce will please take notice. During this period, white people differed from colored to me only in that they rode through town and never lived there. They liked to hear me I I speak pieces" and sing and wanted to see me dance the parse-me-la, and gave me generously of their small silver for doing these things, which seemed strange to me for I wanted to do them so much that I needed bribing to stop, only they didn't know it. The colored people gave no dimes. They deplored any joyful tendencies in me, but I was their Zora nevertheless. I belonged to them, to the nearby hotels, to the countyeverybody's Zora. But changes came in the family when I was thirteen, and I was sent to school in Jacksonville. I left Eatonville, the town of the oleanders, a Zora. When I disembarked from the river-boat at Jacksonville, she was no more. It seemed that I had suffered a sea change. I was not Zora of Orange County any more, I was now a little colored girl. I found it out in certain ways. In my heart as well as in the mirror, I became a fast brown - warranted not to rub nor run. BUT I AM NOT tragically colored. There is no great sorrow dammed up in my soul, nor lurking behind my eyes. I do not mind at all. I do not be long to the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them a lowdown dirty deal and whose feelings are all but about it. Even in the helter-skelter skirmish that is my life, I have seer that the world is to the strong regardless of a little pigmentation more of less. No, I do not weep at the world??I am too busy sharpening my oyster knife. Someone is always at my elbow reminding me that I am the grand daughter of slaves. It fails to register depression with me. Slavery is sixty years in the past. The operation was successful and the patient is doing well, thank you. The terrible struggle that made me an American out of a potential slave said "On the line! " The Reconstruction said "Get set! " and the generation before said "Go! " I am off to a flying start and I must not halt in the stretch to look behind and weep. Slavery is the price I paid for civilization, and the choice was not with me. It is a bully adventure and worth it all that I have paid through my ancestors for it. No one on earth ever had a greater chance for glory. The world to be won and nothing to be lost. It is thrilling to think-to know that for any act of mine, I shall get twice as much praise or twice as much blame. It is quite exciting to hold the center of the national stage, with the spectators not knowing whether to laugh or to weep. The position of my white neighbor is much more difficult. No brown specter pulls up a chair beside me when I sit down to eat. No dark ghost thrusts its leg against mine in bed. The game of keeping what one has is never so exciting as the game of getting. I do not always feel colored. Even now ? I often achieve the unconscious Zora of Eatonville before the Hegira. I feel most colored when I am thrown against a sharp white background. For instance at Barnard. "Beside the waters of the Hudson" I feel my race. Among the thousand white persons, I am a dark rock surged upon, and overswept, but through it all, I remain myself. When covered by the waters, I am; and the ebb but reveals me again. SOMETIMES IT IS the other way around. A white person is set down in our midst, but the contrast is just as sharp for me. For instance, when I sit in the drafty basement that is The New World Cabaret with a white person, my color comes. We enter chatting about any little nothing that we have in common and are seated by the jazz waiters. In the abrupt way that jazz orchestras have, this one plunges into a number. It loses no time in circumlocutions, but gets right down to business. It constricts the thorax and splits the heart with its tempo and narcotic harmonies. This orchestra grows rambunctious, rears on its hind legs and attacks the tonal veil with primitive fury, rending it, clawing it until it breaks through to the jungle beyond. I follow those heathenfollow them exultingly. I dance wildly inside myself; I yell within, I whoop; I shake my assegai above my head, I hurl it true to the mark yeeeeooww! I am in the jungle and living in the jungle way. My face is painted red and yellow and my body is painted blue, My pulse is throbbing like a war drum. I want to slaughter something-give pain, give death to what, I do not know. But the piece ends. The men of the orchestra wipe their lips and rest their fingers. I creep back slowly to the veneer we call civilization with the last tone and find the white friend sitting motionless in his seat, smoking calmly. "Good music they have here," he remarks, drumming the table with his fingertips. Music. The great blobs of purple and red emotion have not touched him. He has only heard what I felt. He is far away and I see him but dimly across the ocean and the continent that have fallen between us. He is so pale with his whiteness then and I am so colored. AT CERTAIN TIMES I have no race, I am me. When I set my hat at a certain angle and saunter down Seventh Avenue, Harlem City, feeling as snooty as the lions in front of the Forty-Second Street Library, for instance. So far as my feelings are concerned, Peggy Hopkins Joyce on the Boule Mich with her gorgeous raiment, stately carriage, knees knocking together in a most aristocratic manner, has nothing on me. The cosmic Zora emerges. I belong to no race nor time. I am the eternal feminine with its string of beads. I have no separate feeling about being an American citizen and colored. I am merely a fragment of the Great Soul that surges within the boundaries. My country, right or wrong. Sometimes, I feel discriminated against, but it does not make me angry. It merely astonishes me. How can any deny themselves the pleasure of my company? It's beyond me. But in the main, I feel like a brown bag of miscellany propped against a wall. Against a wall In company with other bags, white, red and yellow. Pour out the contents, and there is discovered a jumble of small, things priceless and worthless. A first-water diamond, an empty spool bits of broken glass, lengths of string, a key to a door long since crumbled away, a rusty knife-blade, old shoes saved for a road that never was and never will be, a nail bent under the weight of things too heavy for any nail, a dried flower or two still a little fragrant. In your hand is the brown bag. On the ground before you is the jumble it held-so much like the jumble in the bags could they be emptied that all might be dumped in a single heap and the bags refilled without altering the content of any greatly. A bit of colored glass more or less would not matter. Perhaps that is how the Great Stuffer of Bags filled them in the first place-who knows? Their Eyes Were Watching God—Zora Neale Hurston Introduction When Their Eyes Were Watching God first appeared in 1937, it was well-received by white critics as an intimate portrait of southern blacks, but African-American reviewers rejected the novel as pandering to white audiences and perpetuating stereotypes of blacks as happy-go-lucky and ignorant. Unfortunately, the novel and its author, Zora Neale Hurston, were quickly forgotten. But within the last twenty years it has received renewed attention from scholars who praise its unique contribution to African-American literature, and it has become one of the newest and most original works to consistently appear in college courses across the country and to be included in updated versions of the American literary canon. The book has been admired by African-Americanists for its celebration of black culture and dialect and by feminists for its depiction of a woman's progress towards self-awareness and fulfillment. But the novel continues to receive criticism for what some see as its lack of engagement with racial prejudice and its ambivalent treatment of relations between the sexes. No one disputes, though, its impressive use of metaphor, dialect, and folklore of southern rural blacks, which Hurston studied as an anthropologist, to reflect the rich cultural heritage of African-Americans. The Life and Work of Zora Neale Hurston : Author Biography Zora Neale Hurston's colorful life was a strange mixture of acclaim and censure, success and poverty, pride and shame. But her varied life, insatiable curiosity, and profound wit made her one of the most fascinating writers America has known. Even her date of birth remains a mystery. She claimed in her autobiography to have been born on January 7, 1903. but family members swore she was born anywhere from 1891 to 1902. Nevertheless, it is known that she was born in Eatonville, Florida, which was to become the setting for most of her fiction and was the first all-black incorporated town in the nation. Growing up there, where her father was mayor, Hurston was largely sheltered from the racial prejudice African-Americans experienced elsewhere in America. She was the daughter of John Hurston, a Baptist preacher, and Lucy Potts Hurston, a schoolteacher. Zora was the fifth of eight children, and in her autobiography, Dust Tracks on a Road, Hurston fondly remembers growing up in an eight-room house with “...two big chinaberry trees shading the front gate.” Eatonville was a self-governing, independent, allblack town. Her father was mayor for three terms and helped codify the town laws. Hurston grew up believing that blacks were equal, if not superior to whites, and was very proud of her heritage. Hurston used her hometown as a basis for the fictional Eatonville in Their Eyes Were Watching God and even borrowed some real names for her characters. At the age of fourteen, Hurston struck out on her own, working as a maid for white families, and was sent to Morgan Academy in Baltimore by one of her employers. Her educational opportunities continued to grow. She studied at Barnard College, where she worked under the eminent anthropologist Franz Boas. While at Barnard, Hurston developed an interest in anthropology. She studied for years and received several fellowships and grants. Her field of interest was folklore, and she used that extensively in her writings, always seeking to fuse folklore and fiction. Their Eyes Were Watching God was written in seven weeks while she was in Haiti working on a book about voodoo. She also attended Howard University, and Columbia University, where she began work towards a Ph.D. in anthropology. Hurston published her first story in 1921 and quickly gained recognition among the writers of the newly formed Harlem Renaissance, an outpouring of artistic innovation in the African-American community of Harlem. She moved there in 1925 with little money but much ambition, and became well-known as the most colorful member of the artistic and literary circles of the city. She also gained the attention of Mrs. Rufus Osgood Mason, a wealthy white patron who agreed to fund Hurston's trips to Florida where she gathered folklore. Although she married Herbert Sheen during this period, they lived together only eight months before her career came between them. While they split amicably, a later marriage to Albert Price III, which lasted from 1939 to 1943, ended bitterly. Hurston's career as a novelist picked up in the 1930s. Her first novel, Jonah's Gourd Vine, appeared in 1934 and became a Book-of-the-Month Club selection. The following year, she published Mules and Men, a collection of folktales that mixed anthropology and fiction. This book gained her widespread recognition and helped her win a Guggenheim fellowship to study folklore in the West Indies. Before leaving for Haiti, she fell in love with a younger man. When he demanded that she give up her career, she ended the affair, but wrote the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God in seven weeks, translating their romance into the relationship between Janie and Tea Cake. The novel appeared in 1937 to some recognition and controversy. but it quickly receded from the limelight and was not a commercial success. It was Hurston’s third novel. Sadly, the novel received mostly indifferent reviews when first released, including reviews by notable contemporaries. Many of her peers, such as Richard Wright, criticized the novel’s lack of social relevance. They felt that the book was not pertinent in what Mary Helen Washington called “...a decade dominated by Wright and by the stormy fiction of social realism.” Angered by the negative reviews, she began traveling again, and at the request of her publisher, wrote her autobiography in 1942. Her last novel, published in 1948 and called Seraph on the Swanee, was fueled by this anger and was about whites, not blacks. She felt she would be less open to criticism. Around the same time, Hurston was arrested and falsely accused of a morals violation. Although the charges were dismissed, she was demoralized and sick, and retreated to Florida. She spent the last years of her life in poverty, working in various odd jobs. Although she published two more novels, another book of folklore, and dozens of stories, Hurston's literary reputation dwindled throughout the 1940s and '50s. In 1948 she was charged with committing an immoral act with a ten-year-old boy and was later absolved of the crime, but the damage to her public reputation had been done. Hurston felt that she was forever outcast from the African-American literary community of Harlem, so she spent the rest of her life in Florida, where she worked various jobs and tried to keep her head above water financially. When she suffered a stroke in 1959, she was committed to a welfare home where she died penniless and alone in 1960. She was buried in an unmarked grave in the segregated cemetery of Fort Pierce. The location remained unknown until 1973, when it was located by author Alice Walker. Zora Neale Hurston died on January 28, 1960. After her death, her books enjoyed a popular revival, partly due to the efforts of Alice Walker, who was greatly influenced by Hurston. Walker also edited and released a collection of Hurston’s works. Today, Hurston remains one of the most influential black writers in America. Historical Background Hurston arrived in New York in the middle of the Harlem Renaissance. This was part of a historical process which altered black life in America, although it is usually thought of in literary terms. During the 1920s and 30s blacks were migrating to Harlem to escape the racism and oppression of the South. A community of blacks, was forming there and was attracting artists and intellectuals. When she first came to New York, Hurston became involved with Opportunity, a magazine dedicated to “New Negro thought,” the thought that blacks would not accept a subordinate role in society. Hurston was very much a part of this group, and Their Eyes Were Watching God is, among other things, a story of a woman who refuses to be subordinate. However, the only books by blacks that were critically well-received and big sellers during this time were books about the “race problem.” Hurston didn’t write about this. She tried to create a sense of black people as “complete, complex, undiminished human beings.” For her lack of bitterness, she was seen as a traitor by some; others simply didn’t take her seriously, calling her work “folklore fiction.” Additionally, many prominent blacks began to embrace communism, as it was the only political party that called for an end to segregation. Hurston stayed away from politics and was censured for it. Their Eyes Were Watching God was severely criticized for being socially unimportant and actually detrimental to the black cause. Hurston’s peers wanted to be part of the revolution; all she wanted was to tell her story. Narrative Structure Their Eyes Were Watching God is a frame narrative, a story within a story. The omniscient thirdperson sympathetic narrator opens the novel with vivid descriptions of beautiful fortysomething Janie Mae Crawford returning to the Eatonville, Florida home she left two years earlier. Janie herself takes the narrative reigns in the first and last chapters to begin and end her story as she tells it to her best friend Pheoby Watson. The plot unfolds in a series of flashbacks woven together within this framework. Hurston’s narrative strategy allows for the most sympathetic of narrative voices. The narrator, though anonymous, reveals this sympathy through tone and the occasional subtle adoption of Janie’s manner of speaking. While Hurston uses dialogue to reveal information about the other characters, the narrator relays Janie’s thoughts and attitudes directly to the reader. Thus, most of the time, the reader knows exactly what motivates Janie. Hurston’s Harshest Critics Lippincott published Hurston’s piece de resistance, Their Eyes Were Watching God, on September 16, 1937. While it received favorable warm reviews from The New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune, her second novel (her first was Jonah’s Gourd Vine in1934) met with harsh criticism from the black writers and critics of the day. Her loving and careful attempts to preserve what was unique about African-Americans and their communities (dialect, folktales, spirituality, etc.) offended them. A young, and then Communist, Richard Wright, of New Masses, criticized it as a novel carrying “no theme, no message, and no thought.” Apparently, Wright’s eyes were watching for social protest and thus, he dismissed Hurston’s masterpiece as frivolous. Hurston’s onetime Howard University professor Alain Locke similarly criticized Their Eyes…, saying it was not serious fiction. After Words Zora Neale Hurston published four novels, two books of folklore, and a memoirlike autobiography over her thirty-year career. She died penniless on January 28, 1960, after suffering a stroke at the age of sixty-nine. Her grave in Fort Pierce, Florida, remained unmarked until 1973, when author Alice Walker paid for a stone, which reads, “Zora Neale Hurston: A Genius of the South.” Themes Zora Neale Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God charts the development of an AfricanAmerican woman living in the 1920s and 1930s as she searches for her true identity. Search for Self Zora Neale Hurston's Their Eyes Were Watching God charts the development of an AfricanAmerican woman living in the 1920s and 1930s as she searches for her true identity. Although the novel follows Janie through three relationships with men, most critics see its main theme to be Janie's search for herself. She must fight off the influences of her grandmother, who encourages her to sacrifice self-fulfillment for security, and her first two husbands, who stifle her development. Her second husband, Jody, has an especially negative impact on Janie's growth as his bourgeois aspirations turn her into a symbol of his stature in the town. She is not allowed to be herself, but must conform to his notions of propriety, which means she cannot enjoy the talk of the townsfolk on the porch, let alone participate in it. Language and Meaning Integral to Janie's search for self is her quest to become a speaking subject. Language is depicted in the novel as the means by which one becomes a full-fledged member of the community and, hence, a full human being. In Eatonville, the men engage in "eternal arguments, ... a contest in hyperbole and carried on for no other reason." These contests in language are the central activities in the town, but only the men are allowed to participate. Janie especially regrets being excluded, but "gradually, she pressed her teeth together and learned to hush." Race and Racism Although there is very little discussion of relations between whites and blacks in the novel, racism and class differences are shown to have infected the African-American community. The supposed biological and cultural superiority of whiteness hovers over the lives of all the black characters in the book, as Janie witnesses the moral bankruptcy of those who value whiteness over their own black selves. Narration Although the framing device of Janie telling Pheoby her story sets up the novel as Janie's story, it is not told in the first person. Instead, a narrative voice tells most of the story, and there has been much discussion of whose voice this is. The narrator who speaks in standard English, while the characters speak in black dialect, becomes more and more representative of the black community as it progressively adopts the patterns of black vernacular speech. The narrative voice takes on the aspect of oral speech, telling not only Janie's story, but many other stories as well. Folklore One of the most unique features of Their Eyes Were Watching God is its integration of folklore with fiction. Hurston borrows literary devices from the black rural oral tradition, which she studied as an anthropologist, to further cement her privileging of that tradition over the Western literary tradition. For example, she borrows the technique of repetition in threes found commonly in folklore. Also, in the words of Claire Crabtree, "Janie follows a pattern familiar to folklorists of a young person's journey from home to face adventure and various dangers, followed by a triumphant homecoming." In addition, Janie returns "richer and wiser" than she left, and she is ready to share her story with Pheoby, intending that the story be repeated, as a kind of folktale to be passed on. Harlem Renaissance The Harlem Renaissance, which experienced its heyday in Harlem in the 1920s but also flourished well into the 1930s, was an outpouring of creative innovation among blacks that celebrated the achievements of black intellectuals and artists. The initial goal of the writers of the Harlem Renaissance was to overcome racism and convince the white public that AfricanAmericans were more intelligent than the stereotypes of docile, ignorant blacks that pervaded the popular arena. In order to do so, then, most of the early writers associated with the movement imitated the themes and styles of mainstream, white literature. But later writers felt that African-American literature should depict the unique and debilitating circumstances in which blacks lived, confronting their white audiences with scenes of brutal racism. Zora Neale Hurston, considered the most important female member of the Harlem Renaissance, felt that the writings of African-Americans should celebrate the speech and traditions of black people. The use of dialect in Their Eyes Were Watching God caused much controversy among other black writers of the day when it was first published because many felt that such language in the mouths of black characters perpetuated negative stereotypes about blacks as ignorant, but critics today agree that the novel's celebration of black language was the most important contribution Hurston made to African-American literature. Historical Context The Great Depression For southern farmers, both black and white, who did not enjoy the prosperity of northern industrial centers, the Great Depression had begun in the 1920s, well before the stock market crash of 1929. Factors such as soil erosion, the attack of the boll weevil on cotton crops, and the increasing competition from foreign markets led to widespread poverty amongst southern farmers. The majority of African Americans were still farming in the South and they were much harder hit than the white population, even after the advent of President Roosevelt's New Deal. The numbers of blacks on relief were three to four times higher than the number of whites, but relief organizations discriminated by race; some would not help blacks altogether, while others gave lower amounts of aid to blacks than they did to whites. Such practices led one NAACP leader to call the program "the same raw deal." Many critics have criticized Their Eyes Were Watching God for ignoring the plight of African-American farmers in the South during the 1920s and 30s, although Hurston does briefly describe the downtrodden migrant workers who come to pick beans on the muck. The Great Migration and the Harlem Renaissance A large number of African-Americans fought in the first World War under the banner of freedom, only to return home to find how far they were from such a goal. By 1920, over one million blacks had fled the South, where they had little chance of rising out of poverty, and migrated to the industrial centers of the North where they obtained jobs in factories and packing houses, eventually making up as much as twenty percent of the industrial work force there. The migration of blacks to northern cities caused whites to fear that their jobs would be threatened, and increased racial tensions erupted in race riots in 1917. Nonetheless, many blacks began to vocally demand an end to discrimination. Out of this climate came calls for a "New Negro," who would be filled with racial pride and demand justice for his people. While earlier black leaders, represented by Booker T. Washington, had accepted segregation and preached cooperation and patience, new black leaders like W. E. B. DuBois insisted that concessions and appeasements were not the correct approach, and that complete equality could only be achieved by demanding it without compromise. DuBois also believed that the "Talented Tenth," his name for the small percentage of educated blacks, must lead the way for the masses of blacks who still lived in poverty and lacked educational opportunities. DuBois's ideas were reflected in the newly formed black middle class, which, although small, sought to exert an influence on behalf of all blacks. The new efforts of this black elite were centered in Harlem, where a large percentage of migrating blacks ended up, turning the area into a rich, thriving center of black culture. The new energy generated there by jazz musicians, writers, artists, actors, and intellectuals became known as the Harlem Renaissance. This artistic and intellectual movement confronted the racial prejudices of white America by demanding equal recognition for their talent and by depicting the injustices experienced by African-Americans. But ironically, although the artists of the Harlem Renaissance intended their works to promote better conditions for blacks less fortunate than themselves, few blacks around the country were even aware of the movement. In fact, it was more often whites who comprised the audiences and readerships of the products of the Harlem Renaissance. A cult of the primitive, which celebrated all things exotic and sensual, had become all the rage in New York and many wealthy whites flocked to Harlem to witness and participate in the revelry. But wealthy whites were essential to the livelihood of many black artists and writers who relied on their patronage, a fact regretted by many who felt that the artistic products of African-Americans were muted to appeal to the tastes of the whites they depended on. Although the stock market crash of 1929 brought much of the activity in Harlem to an end, the creative energies of those involved had not abated, and many, like Zora Neale Hurston, produced their best work through the 1930s. Race Colonies After the Civil War, former slaves formed a number of all-black towns all over the South, in an effort to escape the segregation and discrimination they experienced amongst whites. By 1914, approximately thirty such towns were in existence. Eatonville, Florida, the town where Zora Neale Hurston grew up and the setting for much of Their Eyes Were Watching God, was the first such town to be incorporated and to win the right of self-governance. In Eatonville, the Jim Crow laws that segregated public schools, housing, restaurants, theaters, and drinking fountains all over the South, did not exist. Discussion Questions—Part 1 1. What kind of God are the eyes of Hurston's characters watching? What is the nature of that God and of their watching? Do any of them question God? 2. What is the importance of the concept of horizon? How do Janie and each of her men widen her horizons? What is the significance of the novel's final sentences in this regard? 3. How does Janie's journey--from West Florida, to Eatonville, to the Everglades--represent her, and the novel's increasing immersion in black culture and traditions? What elements of individual action and communal life characterize that immersion? 4. To what extent does Janie acquire her own voice and the ability to shape her own life? How are the two related? Does Janie's telling her story to Pheoby in flashback undermine her ability to tell her story directly in her own voice? 5. What are the differences between the language of the men and that of Janie and the other women? How do the differences in language reflect the two groups' approaches to life, power, relationships, and self-realization? How do the novel's first two paragraphs point to these differences? 6. In what ways does Janie conform to or diverge from the assumptions that underlie the men's attitudes toward women? How would you explain Hurston's depiction of violence toward women? Does the novel substantiate Janie's statement that "Sometimes God gits familiar wid us womenfolks too and talks His inside business"? 7. What is the importance in the novel of the "signifyin'" and "playin' de dozens" on the front porch of Joe's store and elsewhere? What purpose do these stories, traded insults, exaggerations, and boasts have in the lives of these people? How does Janie counter them with her conjuring? 8. Why is adherence to received tradition so important to nearly all the people in Janie's world? How does the community deal with those who are "different"? 9. After Joe Starks's funeral, Janie realizes that "She had been getting ready for her great journey to the horizons in search of people; it was important to all the world that she should find them and they find her." Why is this important "to all the world"? In what ways does Janie's selfawareness depend on her increased awareness of others? 10. How important is Hurston's use of vernacular dialect to our understanding of Janie and the other characters and their way of life? What do speech patterns reveal about the quality of these lives and the nature of these communities? In what ways are "their tongues cocked and loaded, the only real weapon" of these people? 11. What kind of God are the eyes of Hurston's characters watching? What is the nature of that God and of their watching? Do any of them question God? 12. What symbols or motifs appear in the novel? What do they signify? 13. What is the importance of the concept of horizon? How do Janie and each of her men widen her horizons? What is the significance of the novel's final sentences in this regard? 14. How does Janie's journey--from West Florida, to Eatonville, to the Everglades--represent her, and the novel's increasing immersion in black culture and traditions? What elements of individual action and communal life characterize that immersion? 15. To what extent does Janie acquire her own voice and the ability to shape her own life? How are the two related? Does Janie's telling her story to Pheoby in flashback undermine her ability to tell her story directly in her own voice? 16. What are the differences between the language of the men and that of Janie and the other women? How do the differences in language reflect the two groups' approaches to life, power, relationships, and self-realization? How do the novel's first two paragraphs point to these differences? 17. In what ways does Janie conform to or diverge from the assumptions that underlie the men's attitudes toward women? How would you explain Hurston's depiction of violence toward women? Does the novel substantiate Janie's statement that "Sometimes God gits familiar wid us womenfolks too and talks His inside business"? 18. What is the importance in the novel of the "signifyin'" and "playin' de dozens" on the front porch of Joe's store and elsewhere? What purpose do these stories, traded insults, exaggerations, and boasts have in the lives of these people? How does Janie counter them with her conjuring? 19. Why is adherence to received tradition so important to nearly all the people in Janie's world? How does the community deal with those who are "different"? 20. After Joe Starks's funeral, Janie realizes that "She had been getting ready for her great journey to the horizons in search of people; it was important to all the world that she should find them and they find her." Why is this important "to all the world"? In what ways does Janie's selfawareness depend on her increased awareness of others? 21. How important is Hurston's use of vernacular dialect to our understanding of Janie and the other characters and their way of life? What do speech patterns reveal about the quality of these lives and the nature of these communities? In what ways are "their tongues cocked and loaded, the only real weapon" of these people? Discussion Questions Part II Speech and Silence While Janie tells her story to Phoeby, it becomes apparent that the power of speech and silence plays an important role in developing Janie’s character. Explore how language affects Janie’s development in the novel. When is Janie’s voice stifled? When does Janie feel free to speak out? Does Janie learn to discover her own voice? How so? When is Janie silent in the text? Does this silence empower or weaken her character? When is the narrator silent? Why might this be? Love and Independence While telling her story, Janie describes the relationships she had with her grandmother and three husbands. What different kinds of love has Janie experienced? What is Janie ultimately searching for in a relationship? Why did her first two marriages fail? What was special about her relationship with Tea Cake? Does Janie ultimately succeed in gaining her independence? How so? How do the other characters in the novel react to Janie’s independence? How do the judgments of other members of the community help Janie gain strength and independence? Criticism of Hurston In 1937, Richard Wright reviewed Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God in an article for New Masses. In his review, he wrote, “Miss Hurston voluntarily continues in her novel the tradition which was forced upon the Negro in the theatre, that is, the minstrel technique that makes the ‘white folks’ laugh. Her characters eat and laugh and cry and work and kill; they swing like a pendulum eternally in that safe and narrow orbit in which America like to see the Negro live: between laughter and tears…The sensory sweep of her novel carries no theme, no message, no thought. In the main, her novel is not addressed to the Negro, but to a white audience whose chauvinistic tastes she knows how to satisfy. She exploits that phase of Negro life which is ‘quaint,’ the phase which evokes a piteous smile on the lips of the ‘superior’ race.” Do you agree or disagree with Wright’s interpretation of the novel? Why or why not? Why do you think Wright was so critical of Hurston’s novel? How do you think African Americans are portrayed? How are women portrayed? What message do you think Hurston was trying to convey to her readers in writing this story? Was she successful in doing so? A Sense of Place: Hurston and Florida How does Janie’s journey from West Florida, to Eatonville, to the Everglades and back represent the novel’s increasing immersion in Black culture and traditions? What do the different settings add to the novel? What is symbolic about each? Gender What function does the concept of gender roles have on the meaning of Their Eyes Were Watching God? How could Janie's character be considered "ahead of her time" compared to other women in Their Eyes Were Watching God? In what ways could Janie be read as feminist? Conversely, what weaknesses or flaws might a feminist see in her? Title How do you interpret the title? What tone does it set for our understanding of the novel? How does the title Their Eyes Were Watching God capture some of the main themes of the book? How do the concepts of God, faith, destiny, or sight tie into the plot? In her article “Why don’t he like my hair?”: constructing African American Standards of Beauty in Toni Morrison’s ‘Song of Solomon’ and Zora Neale Hurston’s ‘Their Eyes Were Watching God,’” Bertram Ashe discusses the black female’s unconscious efforts in fitting into an overall white standard of beauty. Read “In Magazines I Found Specimens of the Beautiful” and “Barbie Doll.” Define beauty. Discuss Janie’s characteristics that adhere to the white standards of beauty. Defend, Challenge or Qualify the following statement: Zora Neale Hurston writes Their Eyes Were Watching God for a white audience. Recent scholarship on Their Eyes Were Watching God finds that this complex narrative is underlain by a subtext that subverts the surface text. Susan Willis argues that despite the text's apparent affirmation of black life, Hurston overlooks the realities of class: She chooses not to depict the northern migration of black people, which brought Hurston herself to New York and a college degree and brought thousands of other rural blacks to the metropolis and wage labor More specifically, Willis finds that Hurston's treatment of farm labor minimizes the effects of exploitation: Janie and Tea Cake are really not inscribed within the economics of the "muck." If they plant and harvest beans, they do so because they enjoy fieldwork and because it allows them to live in the heart of southern black cultural production. They are not, like many of the other migrant workers, bowed down by debts and kids.... Janie, with a large inheritance in the bank, need not work at all and Tea Cake, whose forte is gambling, need never accept a job unless he wants it. (49) Similarly, Jennifer Jordan argues that Janie, who is married to Eatonville's mayor and chief property owner, is a privileged bourgeois. To what extent do these comments discredit the novel’s authenticity? Defend, Challenge or Qualify the following statement: In From Behind the Veil, Robert Stepto claims, “Janie has not really won her voice and self after all.” Discuss the significance of the title Their Eyes Were Watching God. The following poem by Eke Omosupe describes the journey of one African American woman in accepting her physical appearance: IN MAGAZINES (I FOUND SPECIMENS OF THE BEAUTIFUL) Once I looked for myself between the covers of Seventeen Vogue Cosmopolitan among blues eyes, blonde hair, white skin thin bodies this is beauty I hated this shroud of Blackness that makes me invisible a negative print some other one's nightmare. In a storefront window against a white backdrop I saw a queenly head of nappy hair and met this chiseled face wide wondering eyes, honey colored, bronzed skin a mouth with thick lips bowed painted red smiled purple gums and shining pearls I turned to leave but this body of curvaceous hips strong thighs broad ass long legs called me back to look again at likenesses of African Queens, Dahomey Warriors, statuesque Goddesses. I stand outside those covers meet Face to Face Myself I am the Beautiful “BARBIE DOLL”—by Marge Piercy This girlchild was born as usual and presented dolls that did pee-pee and miniature GE stoves and irons and wee lipsticks the color of cherry candy. Then in the magic of puberty, a classmate said: You have a great big nose and fat legs. She was healthy, tested intelligent, possessed strong arms and back, abundant sexual drive and manual dexterity. She went to and fro apologizing. Everyone saw a fat nose on thick legs. She was advised to play coy, exhorted to come on hearty, exercise, diet, smile and wheedle. Her good nature wore out like a fan belt. So she cut off her nose and her legs and offered them up. In the casket displayed on satin she lay with the undertaker's cosmetics painted on, a turned-up putty nose, dressed in a pink and white nightie. Doesn't she look pretty? everyone said. Consummation at last. To every woman a happy ending. Major Works Data Sheet—Their Eyes Were Watching God Biographical information about the author: Title: _________Their Eyes Were Watching God_______ Author: ____________Zora Neale Hurston___________ Date of Publication: ___________1937______________ Genre: ___________novel___________________________ ____________________________________________________ Historical information about the period of publication: The decade of the "roaring twenties," a pivotal and turbulent one in American history, was also a period of unprecedented flowering of Black culture, encompassing literature, the visual and plastic arts, as well as the performing arts. Harlem, an area in upper Manhattan where the Black community had been residing since the beginning of the century, became the epicenter of Black cultural life. Life a magnet, Harlem's fame also drew aspiring Black writers from all over the United States and the West Indies into its precincts. For almost two decades (1917-1935), they supplied art to the world. Many southern rural Black Americans came to Harlem in search of economic opportunity and a haven from racial oppression. They brought with them the wealth of oral tradition, regional speech patterns, and rhythms, including the blues and jazz. Black magazines Opportunity and Crisis provided the stimulus for literary competitions. Hurston was born in Eatonville, Florida, to John Hurston, a carpenter and Baptist preacher, and Lucy Ann Potts Hurston, a former country school teacher. In 1918 she graduated from Morgan Academy and entered Howard University. Hurston's first short story was published in Stylus, Howard University's literary magazine. She was an active participant in the Harlem Renaissance, associating with such writers as W. E. B. DuBois, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, and Claude McKay. She received a scholarship to Barnard College where she majored in anthropology. From 1927 to 1931 with the financial assistance of Charlotte Osgood Mason, Hurston traveled throughout the South collecting African American folklore. In 1934 her first novel Jonah's Gourd Vine, was published. In 1936 and 1938 Hurston received Guggenheim Fellow-ships to collect folklore. Throughout her writing career she held a variety of jobs: teaching, writing for a newspaper, and housekeeping. In 1960 Hurston died in poverty and was buried in a segregated cemetery in Fort Pierce, Florida. In 1973, Alice Walker had a tombstone erected on her grave. ___________________________________________ Characteristics of the genre: But the greatest stimulus was the extraordinary wealth of talent compressed into a small section of the big city. Plot Summary: Their Eyes Were Watching God is the story of Janie Crawford, a black woman in Florida, as she searches for love and contentment. The novel is a frame-tale; Janie tells her friend Pheoby what has happened to her and tells Pheoby to pass the story on to others in Eatonville, Florida, where Janie is living. Janie was raised by her grandmother Nanny after Leafy, her mother (and Nanny's daughter by her slaveowner) was raped by the schoolteacher and left town. They live with a white family, the Washburns, and help care for the family and the house. When Janie is sixteen, Nanny sees her kissing Johnny Taylor and decides that it is time for Janie to marry. She arranges it with Logan Killicks, a thirty-year-old man in town, who owns property, a mule, and an organ. A former slave, Nanny does not want Janie to live a life of poverty. Logan, however, treats Janie like a servant. Janie meets Joe (also called Jody) one day near the house and decides to leave Logan and go with Joe. Joe and Janie marry and travel to Eatonville, a new black town, and there Joe buys land and builds the town's general store. For all his promises for the future, Joe treats Janie like a servant as well, assigning her to work in the store and not allowing her to participate in the conversations that take place on the porch. He also tells her to cover her hair so that other men will not have the chance to admire it. Joe wants Janie to behave as "the mayor's wife" and be above the daily comings and goings in the town. The marriage becomes a shell, and Janie learns to keep important feelings and thoughts inside. After twenty years of marriage, Joe dies. A man named Vergible (Tea Cake) Woods arrives in town one day. Younger than Janie by more than ten years, Tea Cake's playful and irreverent attitude appeals to Janie. He teaches her to play checkers, fish, and shoot. She decides to leave Eatonville and go with him to the Florida Everglades where they will work on the muck, planting and picking beans. They spend two happy years there. A hurricane passes through the Everglades, and Janie and Tea Cake try to outrun it. In trying to protect Janie during their escape, Tea Cake is bitten by a rabid dog and develops rabies. The illness makes him mean and irrational. He tries to shoot her, and she kills him in self-defense. She is tried for murder and acquitted. She decides to return to Eatonville and tell her story to Pheoby. Describe the author's style: An example that demonstrates the style: Zora Neale Hurston writes in two narrative styles. Though both are omniscient, they are both seemingly Janie's general outlook on her surroundings. The first is the time-worn Janie, whose experiences have allowed her to look past irrelevant, judgmental, and earthly thoughts in order to make inferences and understand spiritual significance of seemingly concrete occurrences. The tone is insightful, in a dreamily optimistic sense. The other is colloquial, filled with idiomatic expressions and slang terms relative to the time. The narrator is the innocent Janie, who is so caught up in the awe of new experience that she hasn't had time to reflect on past occurrences. The tone is simplistic without ignorance, refreshing without overbearance, matter-of-fact but not objective. The first voice is a philosophical, general perspective that serves more to set the scene, give an exposition, than tell the story. This voice speculates on the tendencies of man and womankind, and although it describes what the novel is about, it doesn't touch on details of specifics. The tone is philosophical and wise. The second voice is more of a narrator in the third person. It surveys the scene and perspectives of all those sitting on the porch. The tone is descriptive and colorful, such as "the great rope of black hair swinging to her waist and unraveling in the wind like a plume." The second voice is obviously necessary n relaying the plot of the novel, but the first serves to relate the events in Janie's life to those in ours, and give it a worldly, universal flavor. It also put Janie's life into perspective and assigns deeper meaning to her varied experiences. "Tea Cake wasn't strange. Seemed as if she had known him all her life. Look how she had been able to talk with him right off! He tipped his hat at the door and he was off with the briefest good night. So she sat on the porch and watched the moon rise. Seen its amber fluid was drenching the earth, and quenching the thirst of the day." (94-95) There are definitely two distinct voice in Their Eyes Were Watching God. One is an omniscient narrator with a scholarly, candid and vibrant tone. The other is the voice of the characters -- the colloquial almost abstruse language that has a realistic and authentic tone. I believe Hurston uses the omniscient narrator to escape from the boundaries of her story, to apply her themes to all people. She uses the second voice to give the story a plausible atmosphere and an interesting, likable twist. (Cameron Walker) Hurston has two distinct voices in the novel. The most often used is that of a narrator who simply describes the events of the plot. This voice blends with the characters. It leaves interpretation up to the reader. The second voice is less a narrator and more of a philosopher. This voice is used to make profound statements that are very figurative in nature. I think Hurston switches back and forth to benefit the readers. She wants them to enjoy the story on a literal and a symbolic level. She leaves the reader to makes his own conclusions and become absorbed in Janie's life. Yet she interrupts to remind the reader that this story has significance and meaning. The two voices are both subjective, but the first to appear elegantly embarks on surreal/metaphysical description, and the second is less omniscient, as it serves as a medium for dialogue. The second acts also as comic relief, but this being thoughtful humor. The two voices act equally, forcing the reader into two essential emotions: laughter and thought. The two voices address the situation from both an internal/real perspective and an external/unreal position. Both are necessary in the development of her stylistic power. They made burning statements with questions, and killing tools out of laughs. It was mass cruelty. A mood come alive. Words walking without masters; walking altogether like harmony in a song. "What she doin' coming back here in dem overhalls? Can't she find no dress to put on?" "They became lords of sounds and lesser things. They passed nations through their mouths. They sat in judgement." "What she doin' coming back here in dem overhalls? Can't she find no dress to put on?" Characters Characters Name Role in the story Significance Adjectives she proves that goals are obtainable, if you put your mind to achieving that goal; Janie teaches us that one cannot be controlled by others; one must control their own actions and be free of restriction by others to be happy. She teaches us that life is a struggle and one must learn from it all. She is significant because she represents only herself: she cannot be a symbol for every black woman. lets the reader gain Janie's perspective and fears about her decision-making process; she cautions and warns Janie;she demonstrates society's idealized woman--caring obediently for her family-She unwittingly spoils Janie's hopes for happiness when she arranges her marriage to Logan Janie's first feelings of lust; Nanny's cue that it is time for Janie to marry; serves as a catalyst for Janie's emerging sexuality helps Janie discern luxury from longing independent, selfconfident, aggressive, extrovert, proud, hard working, admirable, dejected, strong, wise, unique, insatiable, Makes Janie sensitive to the trickery of her own mind; restricts Janie's physical and mental beauty by reasons of jealousy and "duty"; leaves Janie yearning for unfettered , true experience; a false prophet of true love; last and most beloved of Janie's By loving and being loved by Tea Cake, husbands Janie learns what happiness is; and by his death she learns tortuous pain, yet eventual triumph. Janie's soul mate. The one society disapproves, but the one with whom she finds happiness. a flirtatious friend of Tea Cake's in the helps Janie realize her discovery that Everglades she has found love through her jealousy, and that through her love she has found that she is fulfilled A lady that befriends Janie in the muck; Represents racial prejudice within a wants Janie to meet her brother. She race. She favors light-skinned blacks. owns a restaurant on the flat; source of An example of what happens to a conflict; foil to Janie and Tea Cake person's mindset when one's race is held to be inferior to another. dreaming, unfulfilled, scared Janie Mae Crawford Killicks Starks Woods the protagonist--this novel is the story of her life and her loves; the storyteller of her life; Phoeby Wilson Janie's friend and confidante in Eatonville Nanny Crawford Janie's grandmother who raises Janie. Johnny Taylor kissed young Janie over the fence Logan Killicks Janie's first husband; rich; unattractive Leafy Janie's mother who abandoned Janie when Janie was young. She was raped by the schoolteacher. Joe Starks Janie's second husband whose aspirations are inspirational enough to Janie for her to leave her first husband; becomes the mayor of Eatonville, the town he helped to build Vergible (Tea Cake) Woods Nunkie Mrs. Turner friendly, openminded caring, strongwilled, battered "shiftless"; youth; innocence (experienced?) overbearing, unattractive, loving Leafy's story made Janie take advantage depressed, of life, and not throw it away on alcohol abused, lonely, and men. Represents what Nanny is unfortunate, trying to save Janie from and what naive, used Janie strives to avoid. wanderer, loving, innocent, warm, understanding, mesmerizing flirtatious, scheming proud, rude, misled, white acting. Setting The novel starts with Janie's return to Eatonville after Tea Cake's death. Eatonville is significant because it is an allblack town that Janie's second husband Joe Starks was the mayor of before his death. In flash back, the novel tells about Janie's childhood in West Florida, where she grew up with white children on the Washburn's plantation. Then Janie and her grandma moved to their own house. After Janie's first marriage to Logan Killicks, she moved to his sixty-acre farm. Janie wasn't happy despite her security, so she left Logan for Joe Starks, her second husband. Janie and Joe traveled from West Florida to Eatonville, an all-black town where Joe was elected mayor, and Janie had to work in the general store that Joe owned. After Joe's death, Janie left Eatonville with Tea Cake Woods, and they were married in Jacksonville, Florida where he had a job with a railroad shop. They traveled together down to the Florida Everglades, "down on the muck" until a hurricane drove them to Palm Beach temporarily. They went back to the Everglades after the storm had passed, and after Tea Cake's death from rabies, Janie returned alone to Eatonville to live in the house she had shared with Joe Starks. Significance of opening scene The opening chapter emphasizes the differences between the "porch-sitters" of Eatonville, who just sit and talk without accomplishing anything and Janie, who has lived her life to the full. These sitters watched Janie from a distance and judged her. They cruelly cut her down behind her back. In sharp contrast, Janie speaks pleasantly and without malice. She does not stop to waste time on the porch, but goes to her own house. When Pheoby speaks to Janie, they laugh pleasantly without the undercurrent of malice present with the "sitters." From the opening chapter the reader learns that Janie, during her mysterious journey, has gained the composure, humility, and knowledge that the sitters still lack. This sparks our interest to know what she has learned. Symbols Janie's hair - Janie's expression of freedom; when her hair was down, she was free, beautiful, and relaxed; but when Joe makes her wear it up, it is a symbol of her imprisonment and oppression; her youth and her hidden sensuality pear tree blossom - symbolizes Janie's life and her hope and fertility, freshness, oneness with nature; the pollination represents the sensual "marriage" which confuses Janie; becomes Janie's tree of knowledge; Janie's blossoming womanhood and fertility streetlight - Joe's belief that every problem has a simple fix garden seed that Tea Cake leaves behind is the only thing that Janie saves. The seeds represent the future of Janie and Tea Cake's love. lamp post - Biblical allusion to "let there be light"; and Joe's desire to have control and a high standing amongst the townspeople Matt Bonner's mule - Nanny suggest that the Black woman is the mule of the world; Matt uses it as a beast of burden as Logan had used Janie. Joe buys the mule simply so he may look good in the eyes of his community and so that he may possess it. He did the same with Janie when he married her. vultures - symbolize the inhabitants of Eatonville who take apart Janie in a figurative since the same way the vultures literally take apart the mule. Significance of ending/closing scene The novel is a narrative of one woman's self-actualizing journey, and the struggles she endured forging (consciously and subconsciously) this pilgrimage. Thus it serves best for the ending to circle back to the beginning, to the point where all conflicts are solved, and healing can begin. As Janie closes her conversation with Phoeby, and the reader, we all come to terms with Janie's pain and her triumph. The three words "Here was peace," sums up the entire journey, adding a warm, sincere finality to the novel. Janie finishes telling Phoeby her journey and washes her feet--signifying the end of a journey after learning a great deal. As she ascends the stairs the lamp she holds is her own internal light that shines because she is free from the things that have oppressed her all her life. (Kristie Koch) After concluding her story, her loyal friend Phoeby is encouraged and we see the stark contrast between what Janie used to be (Phoeby) and Janie after her life of many experiences and the discovery of freedom. Possible Themes -- Topics of Discussion Love is blind to such carnal qualities as age, social standings and economic stature. Uncovering disillusions in life provides means for growing and understanding love and one’s self. Knowledge of life cannot be taught; it must be learned first0hand through experience.