Industrial Revolution, Romanticism, and individual consciousness

advertisement

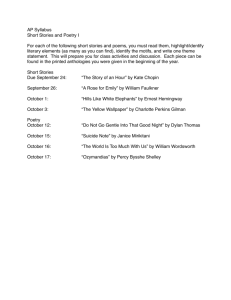

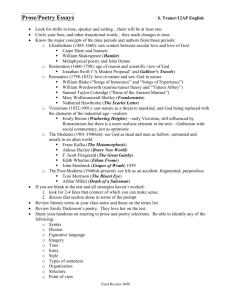

Industrial Revolution, Romanticism, and individual consciousness • We saw how with the Scottish literary revival looked for the authentic plowman poet who performed and consolidated a Scottish identity and created a folk identity for a Anglo-American audience precisely at a moment of social change (industrial, political, and cultural). Industrial Revolution, Romanticism, and individual consciousness • With William Blake we see a similar attention to these changes • In Blake’s time, changes in childhood, instruction, led to new modes of instruction for children (similar to Wollstonecroft’s concern for the education of women there was beginning thought on the education of children and children as having special developmental needs. William Blake • Songs of Innocence and of Experience • “Shewing the two contrary states of the Human Soul” • mostly composed during 1789-94 in 1818 assembled an authoritative print of the book Songs of Innocence and of Experience • An attempt to articulate the changes of individual consciousness • via antithesis • in the context of modern England Songs of Innocence and of Experience • • • • A scene of instruction mother and child reading tree of knowledge Blake v. Isaac Watts (1715) Songs of Innocence and of Experience • The Little Black Boy Songs of Innocence and of Experience • The Ecchoing Green Songs of Innocence and of Experience Holy Thursday Poison Tree • Psychology of guile and deception London • Social Portrait of city mentality Sick rose • Sexual secrecy • invisibility William Wordsworth • 1770-1850 • born in the Lake District in Northern England • Cambridge Educated • 1790s becomes a “fervant democrat” but cools off of revolutionary politics William Wordsworth • Meets Coleridge in the 1790s begins collaboration that would revolutionize English poetry • Lyrical Ballads (1798) • opens with “The Rime Ancient Mariner” and closes with “Lines Written above Tintern Abbey” William Wordsworth • Most great poetry written between 17981807 • 1843 named Poet laureate William Wordsworth • The world is too much with us • Steamboats, Viaducts, and Railways Wordsworth’s double poetic agenda • from “Preface to Lyrical Ballads” • I have said that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity: • the emotion is contemplated till by a species of reaction the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation,is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind. Wordsworth’s double poetic agenda • Observe that this is a reaction against enlightenment rationality • Poetry is not about form or reason or controlled beauty or proportion but spontaneous emotion • and a kind of contemplation that reproduces that emotion • revolution is one of the imagination • social appeal to a new language and purpose for poetry. • Examples in the poems “I wander’d lonely as a cloud” • For oft, when on my couch I lie • In vacant or in pensive mood, • They flash upon that inward eye • Which is the bliss of solitude; • And then my heart with pleasure fills, • And dances with the daffodils Strange Fits of Passion • In one of those sweet dreams I slept, • Kind Nature's gentlest boon! • And all the while my eyes I kept • On the descending moon. • My horse moved on; hoof after hoof • He raised, and never stopped: • When down behind the cottage roof, • At once, the bright moon dropped. • What fond and wayward thoughts will slide • Into a Lover's head! • "O mercy!" to myself I cried, • "If Lucy should be dead!" Tintern Abbey • • • • • • • • • • • • • » These beauteous forms, Through a long absence, have not been to me As is a landscape to a blind man's eye: But oft, in lonely rooms, and 'mid the din Of towns and cities, I have owed to them In hours of weariness, sensations sweet, Felt in the blood, and felt along the heart; And passing even into my purer mind, With tranquil restoration:--feelings too Of unremembered pleasure: such, perhaps, As have no slight or trivial influence On that best portion of a good man's life, His little, nameless, unremembered, acts Of kindness and of love. Tintern Abbey • • • • • • • • • that serene and blessed mood, In which the affections gently lead us on,-Until, the breath of this corporeal frame And even the motion of our human blood Almost suspended, we are laid asleep In body, and become a living soul: While with an eye made quiet by the power Of harmony, and the deep power of joy, We see into the life of things. Tintern Abbey • • • • • • • • • • • • • • May I behold in thee what I was once, My dear, dear Sister! and this prayer I make, Knowing that Nature never did betray The heart that loved her; 'tis her privilege, Through all the years of this our life, to lead From joy to joy: for she can so inform The mind that is within us, so impress With quietness and beauty, and so feed With lofty thoughts, that neither evil tongues, Rash judgments, nor the sneers of selfish men, Nor greetings where no kindness is, nor all The dreary intercourse of daily life, Shall e'er prevail against us, or disturb Our cheerful faith, that all which we behold Is full of blessings. Second part of the agenda • • “The language of • prose may yet be well • adapted to poetry… • and no essential • difference” • • • natural subjects in • states of excitement Solitary Reaper Will no one tell me what she sings?Perhaps the plaintive numbers flow For old, unhappy, far-off things, And battles long ago: Or is it some more humble lay, Familiar matter of to-day? Some natural sorrow, loss, or pain, • That has been, and may be again? • . Second part of the agenda • • “The language of • prose may yet be well adapted to poetry… • and no essential • difference” • • natural subjects in • states of excitement • Solitary Reaper Whate'er the theme, the Maiden sang As if her song could have no ending; I saw her singing at her work, And o'er the sickle bending;-I listened, motionless and still; And, as I mounted up the hill • The music in my heart I bore, • Long after it was heard no more. Samuel Taylor Coleridge • 1772-1834 • Wordsworth’s brilliant collaborator • advocate of the power of the imagination, of the mind as creative in perception On the Imagination (477) • The IMAGINATION then I consider either as primary, or secondary. The primary IMAGINATION I hold to be the living Power and prime Agent of all human perception, and as a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM. The secondary I consider as an echo of the former, co-existing with the conscious will, yet still as identical with the primary in the kind of its agency, and differing only in degree, and in the mode of its operation. It dissolves, diffuses, dissipates, in order to recreate; or where this process is rendered impossible, yet still at all events it struggles to idealize and to unify. It is essentially vital, even as all objects (as objects) are essentially fixed and dead. On Fancy (477-8) • FANCY, on the contrary, has no other counters to play with, but fixities and definites. The Fancy is indeed no other than a mode of Memory emancipated from the order of time and space; and blended with, and modified by that empirical phenomenon of the will, which we express by the word CHOICE. But equally with the ordinary memory it must receive all its materials ready made from the law of association. Kubla Khan • The following fragment is here published at the request of a poet of great and deserved celebrity [Lord Byron], and, as far as the Author's own opinions are concerned, rather as a psychological curiosity, than on the ground of any supposed poetic merits. • In the summer of the year 1797, the Author, then in ill health, had retired to a lonely farm-house between Porlock and Linton, on the Exmoor confines of Somerset and Devonshire. In consequence of a slight indisposition, an anodyne had been prescribed, from the effects of which he fell asleep in his chair at the moment that he was reading the following sentence, or words of the same substance, in Purchas's Pilgrimage: ``Here the Khan Kubla commanded a palace to be built, and a stately garden thereunto. And thus ten miles of fertile ground were inclosed with a wall.'' Kubla Khan • The Author continued for about three hours in a profound sleep, at least of the external senses, during which time he has the most vivid confidence, that he could not have composed less than from two to three hundred lines; if that indeed can be called composition in which all the images rose up before him as things, with a parallel production of the correspondent expressions, without any sensation or consciousness of effort. On awakening he appeared to himself to have a distinct recollection of the whole, and taking his pen, ink, and paper, • instantly and eagerly wrote down the lines that are here preserved. At this moment he was unfortunately called out by a person on business from Porlock, and detained by him above an hour, and on his return to his room, found, to his no small surprise and mortification, that though he still retained some vague and dim recollection of the general purport of the vision, yet, with the exception of some eight or ten scattered lines and images, all the rest had passed away like the images on the surface of a stream into which a stone has been cast, but, alas! without the after restoration of the latter! Kubla Khan • Then all the charm • Is broken--all that phantom-world so fair • Vanishes, and a thousand circlets spread, • And each mis-shape the other. Stay awile, • Poor youth! who scarcely dar'st lift up thine eyes-• The stream will soon renew its smoothness, soon • The visions will return! And lo, he stays, • And soon the fragments dim of lovely forms • Come trembling back, unite, and now once more • The pool becomes a mirror. • Yet from the still surviving recollections in his mind, the Author has frequently purposed to finish for himself what had been • originally, as it were, given to him. : but the to-morrow is yet to come. • As a contrast to this vision, I have annexed a fragment of a very different character, describing with equal fidelity the dream of • pain and disease. John Keats • 1795-1821 • son of a London stableman • took up poetry at 18 • studied medicine • 1819 was producing great works and gaining recognition • Becomes ill with consumption • Dies in Rome in search of health George Gordon, Lord Byron • 1788-1824 • most popular and dashing of Romantic figures • created mythic hero • Byronic hero alien, mysterious, gloomy, superior • self-reliant rebel, exile • sexual scandals follow him • dies in Greece fighting the Turks Percy Bysshe Shelley • 1792-1822 • radical nonconformist always taking up radical causes • Harriet Westbrook • Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin flees to France with her • a life of exile • Dies in boating acccident in Pisa Ozymandias • • • • • • • • • • • • • • I met a traveller from an antique land Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed; And on the pedestal these words appear: "My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!" Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away. Felicia Dorothea Hemans • 1793 - 1835 • precocious daughter of Liverpool merchants • died at 41 • very popular • known for her pieces that became standard recitation pieces Casabianca • The boy stood on the burning deck • Whence all but he had fled; • The flame that lit the battle's wreck • Shone round him o'er the dead. • Yet beautiful and bright he stood, • As born to rule the storm; • A creature of heroic blood, • A proud, though child-like form. • The flames rolled onhe would not go • Without his Father's word; • That father, faint in death below, • His voice no longer heard. • He called aloud'say, Father, say • If yet my task is done?' • He knew not that the chieftain lay • Unconscious of his son. Casabianca • 'Speak, father!' once again he cried, • 'If I may yet be gone!' • And but the booming shots replied, • And fast the flames rolled on. • And shouted but once more aloud, • 'My father! must I stay?' • While o'er him fast, through sail and shroud, • The wreathing fires made way. • Upon his brow he felt their breath, • And in his waving hair, • And looked from that lone post of death • In still yet brave despair. • They wrapt the ship in splendour wild, • They caught the flag on high, • And streamed above the gallant child, • Like banners in the sky. Casabianca • There came a burst of thunder sound • The boyoh! where was he? • Ask of the winds that far around • With fragments strewed the sea! • With mast, and helm, and pennon fair, • That well had borne their part • But the noblest thing which perished there • Was that young faithful heart. • Notes: • 1.Young Casabianca, a boy about thirteen years old, son of the admiral of the Orient, remained at his post (in the Battle of the Nile), after the ship had taken fire, and all the guns had been abandoned; and perished in the explosion of the vessel, when the flames had reached the powder.