Environmental and

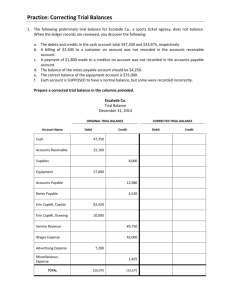

Theoretical Structure

of Financial

Accounting

Insert Book Cover

Picture

1

Copyright © 2007 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

1-2

Learning Objectives

Describe the function and primary

focus of financial accounting.

1-3

Financial Accounting Environment

Providers of

Financial Information

Profit-oriented

companies

Not-for-profit

entities

Households

External

User Groups

Relevant

Financial

Information

Investors

Creditors

Employees

Labor unions

Customers

Suppliers

Government

agencies

Financial

intermediaries

1-4

Financial Accounting Environment

Relevant financial information is provided

primarily through financial statements and

related disclosure notes.

Balance Sheet

Income Statement

Statement of Cash Flows

Statement of Shareholders’ Equity

The Economic Environment and

Financial Reporting

A sole proprietorship

is owned by a

single individual.

A partnership is

owned by two or

more individuals.

A corporation is owned

by stockholders,

frequently numbering

in the tens of thousands

in large corporations.

A highly-developed system of financial

reporting is necessary to communicate

financial information from a corporation

to its many shareholders.

1-5

Investment-Credit Decisions

A Cash Flow Perspective

Corporate shareholders receive cash from

their investments through . . .

Periodic dividend distributions from the

corporation.

The ultimate sale of the ownership shares of

stock.

1-6

Investment-Credit Decisions

A Cash Flow Perspective

Accounting information should help

investors evaluate the amount, timing,

and uncertainty of the enterprise’s

future cash flows.

1-7

1-8

Learning Objectives

Explain the difference between

cash and accrual accounting.

1-9

Cash Versus Accrual Accounting

Cash Basis Accounting

Revenue is recognized when cash is received.

Expenses are recognized when cash is paid.

1-10

Cash Versus Accrual Accounting

Cash Basis Accounting

Carter Company has sales on account totaling

$100,000 per year for three years. Carter collected

$50,000 in the first year and $125,000 in the second

and third years. The company prepaid $60,000 for

three years’ rent in the first year. Utilities are $10,000

per year, but in the first year only $5,000 was paid.

Payments to employees are $50,000 per year.

Let’s look at the cash flows.

1-11

Cash Versus Accrual Accounting

Cash Basis Accounting

Year 1

Cash receipts from

customers

$ 50,000

Summary of Cash Flows

Year 2

Year 3

$ 125,000

$ 125,000

Total

$ 300,000

Payment of 3

years' rent

(60,000)

-

-

(60,000)

Salaries to

employees

(50,000)

(50,000)

(50,000)

(150,000)

(5,000)

$ (65,000)

(15,000)

$ 60,000

(10,000)

$ 65,000

(30,000)

$ 60,000

Payments for

utilities

Net cash flow

1-12

Cash Versus Accrual Accounting

Cash Basis Accounting

Year 1

Cash receipts from

customers

$ 50,000

Payment of 3

years' rent

(60,000)

Summary of Cash Flows

Year 2

Year 3

$ 125,000

-

$ 125,000

-

Total

$ 300,000

(60,000)

Salaries to

Cash flows

in any one

year may(50,000)

not be a (150,000)

employees

(50,000)

(50,000)

Payments for

utilities

Net cash flow

predictor of future cash flows.

(5,000)

$ (65,000)

(15,000)

$ 60,000

(10,000)

$ 65,000

(30,000)

$ 60,000

1-13

Cash Versus Accrual Accounting

Accrual Accounting

Revenue is recognized when earned.

Expenses are recognized when incurred.

Let’s reconsider the Carter

Company information.

1-14

Cash Versus Accrual Accounting

Accrual Accounting

Revenue is recognized when earned.

Expenses are recognized when incurred.

Let’s reconsider the Carter

Company information.

1-15

Learning Objectives

Define generally accepted accounting

principles (GAAP) and discuss the historical

development of accounting standards.

The Development of Financial Accounting

and Reporting Standards

Concepts,

principles, and

procedures were

developed to meet the

needs of external

users (GAAP).

1-16

1-17

Historical Perspective and Standards

Securities and Exchange Commission

1934 – present

Evolution of Standard-Setting Process

1938 – 1959:

Committee on Accounting Procedures (CAP)

1959 – 1973:

Accounting Principles Board (APB)

Current Standard Setting - FASB

www.fasb.org

Supported by the Financial Accounting

Foundation.

Seven full-time, independent voting members

serving for 10 years.

Answerable only to the Financial Accounting

Foundation.

Members not required to be CPAs.

1-18

1-19

Learning Objectives

Explain why the establishment of

accounting standards is characterized

as a political process.

Establishment of Accounting Standards

A Political Process

Internal Revenue

Service

www.irs.gov

American Institute

of CPAs

www.aicpa.org

Securities and

Exchange

Commission

www.sec.gov

Financial Executives

International

www.fei.org

GAAP

Governmental

Accounting

Standards Board

www.gasb.org

American

Accounting

Association

www.aaa-edu.org

1-20

1-21

FASB’s Standard-Setting Process

Identification of problem.

The task force.

Research and analysis.

Discussion memorandum.

Public response.

Exposure draft.

Public response.

Statement issued.

International Accounting Standards

Board (IASB)

Established in 1973 to narrow the

range of differences in accounting

standards.

Increase in international trade has

motivated the IASB to attempt to

eliminate alternative accounting

treatments.

1-22

1-23

Role of the Auditor

Independent intermediary to help insure that

management has in fact appropriately

applied GAAP.

1-24

Financial Reporting Reform

As a result of numerous financial scandals,

Congress passed the Public Company

Accounting Reform and Investor Protection

Act of 2002, commonly referred to as the

Sarbanes-Oxley Act for the two congressmen

who sponsored the bill.

1-25

Learning Objectives

Explain the purpose of the

FASB’s conceptual framework.

1-26

The Conceptual Framework

Maintain consistency among standards.

Resolve new accounting problems.

Provide user benefits.

1-27

Learning Objectives

Identify the objectives of financial reporting, the

qualitative characteristics of accounting

information, and the elements of financial

statements.

Describe the four basic

assumptions underlying GAAP

Describe the four basic accounting

principles that guide accounting practice.

1-28

Objectives

Qualitative

Characteristics

Understandability

Primary

Relevance

Reliability

Secondary

Comparability

Consistency

Elements

Assets

Liabilities

Equity

Investments by Owners

Distributions to owners

Revenues

Expenses

Gains

Losses

Comprehensive Income

Financial Statements

Constraints

Cost effectiveness

Materiality

Conservatism

Balance sheet

Income statement

Statement of cash flows

Statement of shareholders’ equity

Related disclosures

Recognition and

Measurement

Concepts

Assumptions

Economic entity

Going concern

Periodicity

Monetary unit

Principles

Historical cost

Realization

Matching

Full Disclosure

1-29

Qualitative Characteristics of

Accounting Information

Decision Usefulness

Relevance

Predictive

Value

Feedback

Value

Comparability

Reliability

Timeliness

Verifiability

Neutrality

Consistency

Representational

Faithfulness

Practical Constraints to Achieving

Desired Qualitative Characteristics

Conservatism

Cost

Effectiveness

Materiality

1-30

SFAC No. 6

Assets and Liabilities

Assets are probable future economic benefits

obtained or controlled by a particular entity as a

result of past transactions or events.

Liabilities are probable future sacrifices of

economic benefits arising from present

obligations of a particular entity to transfer or

provide services to other entities in the future as

a result of past transactions or events.

1-31

SFAC No. 6

Equity

Equity, or net assets, called shareholders’

equity or stockholders’ equity for a

corporation, is the residual interest in the

assets of an entity that remains after

deducting liabilities.

1-32

SFAC No. 6

Investments and Distributions

Investments by owners are increases in

equity resulting from transfers of resources

(usually cash) to a company in exchange

for ownership interest.

Distributions to owners are decreases in

equity resulting from transfers to the

owners.

1-33

SFAC No. 6

Revenues

Revenues are inflows or other

enhancements of assets or settlements of

liabilities from delivering or producing

goods, rendering services, or other

activities that constitute the entity’s

ongoing major, or central, operations.

1-34

SFAC No. 6

Expenses

Expenses are outflows or other using up of

assets or incurrences of liabilities during a

period from delivering or producing goods,

rendering services, or other activities that

constitute the entity’s ongoing major, or

central, operations.

1-35

SFAC No. 6

Gains and Losses

Gains are increases in equity peripheral, or

incidental, transactions of an entity.

Losses represent decreases in equity arising

from peripheral, or incidental, transactions

of an entity.

1-36

SFAC No. 6

Comprehensive Income

Comprehensive income is the change in equity

of a business enterprise during a period from

transactions and other events and

circumstances from nonowner sources. It

includes all changes in equity during a period

except those resulting from investments from

owners and distributions to owners.

1-37

1-38

Recognition and Measurement Concepts

Review of the

Accounting

Process

Insert Book Cover

Picture

2

Copyright © 2007 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

1-40

The Basic Model

Economic events cause

changes in the financial

position of a company.

External events

involve an exchange

between the company

and another entity.

Internal events do not

involve an exchange

transaction but do

affect the company’s

financial position.

1-41

Learning Objectives

Analyze routine economic events—

transactions—and record their effects on a

company’s financial position using the

accounting equation format.

1-42

Accounting Equation for a Corporation

A = L + SE

+ Paid-in Capital

+ Retained Earnings

+ Revenues - Expenses - Dividends

+ Gains

- Losses

1-43

Account Relationships

Debits and credits affect the Balance Sheet

Model as follows:

A = L + PIC + RE

Assets

Dr. Cr.

+

-

Liabilities

Dr. Cr.

+

Paid-in

Capital

Dr. Cr.

+

Retained

Earnings

Dr. Cr.

+

Revenues

and Gains

Dr. Cr.

+

Expenses

and Losses

Dr. Cr.

+

-

1-44

Source

documents

Transaction

Analysis

Record in

Journal

Post to

Ledger

Financial

Statements

Adjusted

Trial Balance

Record & Post

Adjusting

Entries

Unadjusted

Trial Balance

Close Temporary

Accounts

Post-Closing

Trial Balance

The

Accounting

Processing

Cycle

1-45

Learning Objectives

Record transactions using the general journal

format.

1-46

Accounting Processing Cycle

On January 1, 2007, $40,000 was borrowed

from a bank and a note payable was signed.

Two accounts are affected:

Cash (an asset) increases by $40,000.

Notes Payable (a liability) increases by $40,000.

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Page

Post.

Ref.

Prepare

the

journal

entry.

Cash

40,000

Description

Jan 1

Account

numbers are

Payable

references for Notes

posting

to

the General Ledger.

Debit

1

Credit

40,000

1-47

General Ledger

GENERAL LEDGER

Account:

Acct. No.

##

Balance

Date

Item

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

The “T” account is a shorthand used by

accountants to analyze transactions. It

is not part of the bookkeeping system.

DR (CR)

1-48

Learning Objectives

Post the effects of journal entries to T-accounts

and prepare an unadjusted trial balance.

1-49

Posting Journal Entries

On July 1, 2006, the owners invest $60,000 in a new

business, Dress Right Clothing Corporation.

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

July 1 Cash

Page

Post.

Ref.

Debit

1

Credit

60,000

Common Stock

60,000

Post the debit portion of the entry to the Cash ledger account.

1-50

Posting Journal Entries

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Page

Post.

Ref.

Description

July 1 Cash

1

Debit

Credit

60,000

Common Stock

60,000

GENERAL LEDGER

Account: Cash

Date

1

Item

Acct. No.

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

100

Balance

1-51

Posting Journal Entries

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Page

Post.

Ref.

Description

July 1 Cash

Debit

Credit

60,000

Common Stock

2

60,000

GENERAL LEDGER

Account: Cash

Date

July

1

1

3

Acct. No.

Item

Post.

Ref.

Debit

60,000

Credit

100

Balance

1-52

Posting Journal Entries

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Page

Post.

Ref.

Description

1

Debit

July 1 Cash

Credit

60,000

Common Stock

60,000

4

GENERAL LEDGER

Account: Cash

Date

July

1

Acct. No.

Item

Post.

Ref.

J1

100

5

Debit

60,000

Credit

Balance

60,000

1-53

Posting Journal Entries

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Page

Post.

Ref.

Description

July 1 Cash

100

1

Debit

Credit

60,000

Common Stock

60,000

6

GENERAL LEDGER

Account: Cash

Date

July

1

Acct. No.

Item

Post.

Ref.

J1

Debit

60,000

Credit

100

Balance

60,000

1-54

Posting Journal Entries

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Page

Post.

Ref.

Description

July 1 Cash

100

1

Debit

Credit

60,000

Common Stock

60,000

Post the credit portion of the entry to the Common Stock ledger

account.

GENERAL LEDGER

Account: Common Stock

Date

Item

1

Post.

Ref.

Acct. No.

Debit

Credit

300

Balance

1-55

Posting Journal Entries

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Page

Post.

Ref.

Description

July 1 Cash

100

Debit

60,000

GENERAL LEDGER

Account: Common Stock

Date

July

1

Item

Post.

Ref.

Credit

60,000

Common Stock

2

1

Debit

3

Acct. No.

300

Credit

60,000

Balance

1-56

Posting Journal Entries

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Page

Post.

Ref.

Description

July 1 Cash

100

1

Debit

Credit

60,000

Common Stock

60,000

4

GENERAL LEDGER

Account: Common Stock

Date

July

1

Item

Acct. No.

Post.

Ref.

J1

300

5

Debit

Credit

60,000

Balance

60,000

1-57

Posting Journal Entries

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Page

Post.

Ref.

Description

July 1 Cash

100

300

Common Stock

1

Debit

Credit

60,000

60,000

6

GENERAL LEDGER

Account: Common Stock

Date

July

1

Item

Acct. No.

Post.

Ref.

J1

Debit

Credit

60,000

300

Balance

60,000

1-58

After recording all entries for the period, Dress

Right’s Trial Balance would be as follows:

Dress Right Clothing Corporation

Unadjusted Trial Balance

July 31, 2006

Account Title

Cash

Accounts receivable

Supplies

Prepaid rent

Inventory

Furniture and fixtures

Accounts payable

Notes payable

Unearned rent revenue

Common stock

Retained earnings

Sales revenue

Cost of goods sold

Salaries expense

Total

Debits

$ 68,500

2,000

2,000

24,000

38,000

12,000

Credits

$

35,000

40,000

1,000

60,000

A Trial

Balance is a

listing of all

accounts

and their

balances at

a point in

time.

1,000

38,500

22,000

5,000

$ 174,500

$ 174,500

Debits = Credits

1-59

Adjusting Entries

At the end of the period,

some transactions or

events remain

unrecorded.

Because of this, several

accounts in the ledger

need adjustments

before their balances

appear in the financial

statements.

1-60

Learning Objectives

Identify and describe the different types of

adjusting journal entries.

Determine the required adjustments, record

adjusting journal entries in general journal

format, and prepare an adjusted trial balance.

1-61

Adjusting Entries

Prepayments

(Deferrals)

Transactions

where cash is

paid or received

before a related

expense or

revenue is

recognized.

Accruals

Transactions

where cash is

paid or received

after a related

expense or

Estimates

1-62

Alternative Approach to Record Prepayments

Prepaid Expenses

Record initial cash

payments as follows:

Expense

Cash

$$$

$$$

Adjusting Entry

Record the amount for the

prepaid expense as

follows:

Prepaid expense

Expense

$$

$$

Unearned Revenue

Record initial cash receipts

as follows:

Cash

Revenue

$$$

$$$

Adjusting Entry

Record the amount for the

unearned liability as

follows:

Revenue

$$

Unearned revenue $$

1-63

Accrued Liabilities

Last pay

date

7/20/06

7/1/06

Next pay

date

8/2/06

7/31/06

Month end

Record adjusting

journal entry.

On July 31, 2006, the

employees have earned

salaries of $5,500.

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

July 31 Salaries Expense

Salaries Payable

Page 30

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

5,500

5,500

1-64

Accrued Receivables

Assume that Dress Right loaned another corporation

$30,000 at the beginning of August. Terms of the note

call for the payment of principal, $30,000, and interest at

8% in three months.

First, let’s determine the amount of interest to accrue at

August 31, 2006.

P×R×T

$30,000

.08

Interest = $200

1/

12

1-65

Accrued Receivables

Assume that Dress Right loaned another corporation

$30,000 at the beginning of August. Terms of the note

call for the payment of principal, $30,000, and interest at

8% in three months.

Now, let’s prepare the adjusting entry for August 31, 2006.

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

Aug. 31 Interest Receivable

Interest Revenue

Page 30

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

200

200

1-66

Estimates

Uncollectible

accounts and

depreciation of fixed

assets are estimated.

An

estimated item is

a function of future

events and

developments.

$

1-67

Estimates

The estimate of bad debt expense at the end of the

period is an example of an adjusting entry that requires

an estimate.

Assume that Dress Right’s management determines that

of the $2,000 of accounts receivable recorded at July 31,

2006, only $1,500 will ultimately be collected. Prepare

the adjusting entry for July 31, 2006.

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

July 31 Bad Debt Expense

Allowance for Uncollectible

Accounts

Page 30

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

500

500

DRESS RIGHT CLOTHING CORPORATION

Adjusted Trial Balance

July 31, 2006

Account Title

Debits

Credits

Cash

$

68,500

Accounts receivable

2,000

Allowance for uncollectible accounts

$

500

Supplies

1,200

Prepaid rent

22,000

Inventory

38,000

Furniture and fixtures

12,000

Accumulated depr.-furniture & fixtures

200

Accounts payable

35,000

Note payable

40,000

Unearned rent revenue

750

Salaries payable

5,500

Interest payable

333

Common stock

60,000

Retained earnings

1,000

Sales revenue

38,500

Rent revenue

250

Cost of goods sold

22,000

Salaries expense

10,500

Supplies expense

800

Rent expense

2,000

Depreciation expense

200

Interest expense

333

Bad debt expense

500

Totals

$ 181,033 $ 181,033

1-68

This is the Adjusted

Trial Balance for

Dress Right after all

adjusting entries have

been recorded and

posted.

Dress Right will use

these balances to

prepare the financial

statements.

1-69

Learning Objectives

Describe the four basic financial statements.

1-70

Dress Right Clothing Corporation

Income Statement

For Month Ended July 31, 2006

Sales revenue

$

Cost of goods sold

Gross profit

Other expenses:

Salaries

$

10,500

Supplies

800

Rent

2,000

Depreciation

200

Bad debt

500

Total operating expenses

Operating income

Other income (expense):

Rent revenue

250

Interest expense

(333)

Net income

$

38,500

22,000

16,500

14,000

2,500

(83)

2,417

The income statement summarizes the results of

operating activities of the company.

1-71

Dress Right Clothing Corporation

Balance Sheet

At July 31, 2006

Assets

Current assets:

Cash

Accounts receivable

Less: Allowance for uncollectible accounts

Supplies

Inventory

Prepaid rent

Total current assets

Property and equipment:

Furniture and fixtures

Less: Accumulated depreciation

Total assets

$

$

2,000

500

68,500

1,500

1,200

38,000

22,000

131,200

12,000

200

$

11,800

143,000

The balance sheet presents the financial position

of the company on a particular date.

1-72

Dress Right Clothing Corporation

Balance Sheet

At July 31, 2006

Liabilities and Shareholders' Equity

Current liabilities:

Accounts payable

$

Salaries payable

Unearned rent revenue

Interest payable

Note payable

Total current liabilities

Long-term liabilities:

Note payable

Shareholders' equity:

Common stock

$

60,000

Retained earnings

1,417

Total shareholders' equity

Total liabilities and shareholders' equity

$

35,000

5,500

750

333

10,000

51,583

30,000

61,417

143,000

The balance sheet presents the financial position

of the company on a particular date.

1-73

Dress Right Clothing Corporation

Statement of Cash Flows

For the Month of July 2006

Cash flows from operating activities:

Cash inflows:

From customers

$

From rent

Cash outflows:

For rent

For supplies

To suppliers for merchandise

To employees

Net cash used by operating activities

Cash flows from investing activities:

Purchase of furniture and fixtures

Cash flows from financing activities:

Issue of capital stock

$

Increase in notes payable

Payment of cash dividend

Net cash provided by financing activities

Net increase in cash

36,500

1,000

(24,000)

(2,000)

(25,000)

(5,000)

$

(18,500)

(12,000)

60,000

40,000

(1,000)

$

99,000

68,500

The statement of cash flows discloses the

changes in cash during a period.

1-74

Dress Right Clothing Corporation

Statement of Shareholders' Equity

For the Month of July 2006

Balance at July 1, 2006

Issue of capital stock

Net income for July 2006

Less: Dividends

Balance at July 31, 2006

Common Retained

Stock

Earnings

$

$

60,000

2,417

(1,000)

$

60,000 $

1,417

Total

Shareholders'

Equity

$

60,000

2,417

(1,000)

$

61,417

The statement of shareholders’ equity presents

the changes in permanent shareholder accounts.

1-75

Learning Objectives

Explain the closing process.

1-76

The Closing Process

Resets revenue, expense

and dividend account

balances to zero at the

end of the period.

Helps summarize a

period’s revenues and

expenses in the Income

Summary account.

Identify accounts for

closing.

Record and post closing

entries.

Prepare post-closing trial

balance.

1-77

Temporary and Permanent Accounts

Income

Summary

Liabilities

Permanent

Accounts

Shareholders’

Equity

Temporary

Accounts

Assets

Dividends

Expenses

Revenues

The closing process applies

only to temporary accounts.

1-78

Closing Entries

Close Revenue

accounts to Income

Summary.

Close Expense

accounts to Income

Summary.

Close Income Summary

account to Retained

Earnings.

Let’s prepare the

closing entries for

Dress Right.

DRESS RIGHT CLOTHING CORPORATION

Adjusted Trial Balance

July 31, 2006

Account Title

Debits

Credits

Cash

$

68,500

Accounts receivable

2,000

Allowance for uncollectible accounts

$

500

Supplies

1,200

Prepaid rent

22,000

Inventory

38,000

Furniture and fixtures

12,000

Accumulated depr.-furniture & fixtures

200

Accounts payable

35,000

Note payable

40,000

Unearned rent revenue

750

Salaries payable

5,500

Interest payable

333

Common stock

60,000

Retained earnings

1,000

Sales revenue

38,500

Rent revenue

250

Cost of goods sold

22,000

Salaries expense

10,500

Supplies expense

800

Rent expense

2,000

Depreciation expense

200

Interest expense

333

Bad debt expense

500

Totals

$ 181,033 $ 181,033

1-79

Close Revenue

accounts to

Income Summary.

Close Revenue Accounts to Income

Summary

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

July 31 Sales Revenue

Rent Revenue

1-80

Page 34

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

38,500

250

Income Summary

Now, let’s look at the ledger accounts after

posting this closing entry.

38,750

Close Revenue Accounts to Income

Summary

1-81

Sales Revenue

38,500

38,500

-

Income Summary

38,750

38,750

Rent Revenue

250

250

-

DRESS RIGHT CLOTHING CORPORATION

Adjusted Trial Balance

July 31, 2006

Account Title

Debits

Credits

Cash

$

68,500

Accounts receivable

2,000

Allowance for uncollectible accounts

$

500

Supplies

1,200

Prepaid rent

22,000

Inventory

38,000

Furniture and fixtures

12,000

Accumulated depr.-furniture & fixtures

200

Accounts payable

35,000

Note payable

40,000

Unearned rent revenue

750

Salaries payable

5,500

Interest payable

333

Common stock

60,000

Retained earnings

1,000

Sales revenue

38,500

Rent revenue

250

Cost of goods sold

22,000

Salaries expense

10,500

Supplies expense

800

Rent expense

2,000

Depreciation expense

200

Interest expense

333

Bad debt expense

500

Totals

$ 181,033 $ 181,033

1-82

Close Expense

accounts to

Income Summary.

Close Expense Accounts to Income

Summary

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

July 31 Income Summary

1-83

Page 34

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

36,333

Cost of goods sold

22,000

Salaries expense

10,500

Supplies expense

800

Rent expense

2,000

Depreciation expense

200

Interest expense

333

Bad debts expense

500

Now, let’s look at the ledger accounts after

posting this closing entry.

Bad Debts Exp.

500

500

-

Close Expense Accounts to

Income Summary

Depreciation Exp.

200

200

-

Rent Expense

2,000

2,000

-

Salaries Expense

10,500

10,500

-

Supplies Expense

800

800

-

Interest Expense

333

333

-

Cost of Goods Sold

22,000

22,000

-

1-84

Income Summary

36,333 38,750

2,417

Net Income

DRESS RIGHT CLOTHING CORPORATION

Adjusted Trial Balance

July 31, 2006

Account Title

Debits

Credits

Cash

$

68,500

Accounts receivable

2,000

Allowance for uncollectible accounts

$

500

Supplies

1,200

Prepaid rent

22,000

Inventory

38,000

Furniture and fixtures

12,000

Accumulated depr.-furniture & fixtures

200

Accounts payable

35,000

Note payable

40,000

Unearned rent revenue

750

Salaries payable

5,500

Interest payable

333

Common stock

60,000

Retained earnings

1,000

Sales revenue

38,500

Rent revenue

250

Cost of goods sold

22,000

Salaries expense

10,500

Supplies expense

800

Rent expense

2,000

Depreciation expense

200

Interest expense

333

Bad debt expense

500

Totals

$ 181,033 $ 181,033

1-85

Close Income

Summary to

Retained

Earnings.

Close Income Summary to Retained

Earnings

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

July 31 Income Summary

1-86

Page 34

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

2,417

Retained Earnings

Now, let’s look at the ledger accounts after

posting this closing entry.

2,417

Close Income Summary to Retained

Earnings

Retained Earnings

1,000

2,417

1,417

Income Summary

36,333 38,750

2,417

-

1-87

1-88

Post-Closing Trial Balance

DRESS RIGHT CLOTHING CORPORATION

Post-Closing Trial Balance

July 31, 2006

Account Title

Debits

Credits

Cash

$

68,500

Accounts receivable

2,000

Allowance for uncollectible accounts

$

500

Supplies

1,200

Prepaid rent

22,000

Inventory

38,000

Furniture and fixtures

12,000

Accumulated depr.-furniture & fixtures

200

Accounts payable

35,000

Note payable

40,000

Unearned rent revenue

750

Salaries payable

5,500

Interest payable

333

Common stock

60,000

Retained earnings

1,417

Totals

$ 143,700 $ 143,700

Lists permanent

accounts and their

balances.

Total debits equal

total credits.

1-89

Reversing

Entries

Appendix 2B

1-90

Reversing Entries

Reversing entries remove the effects of some of

the adjusting entries made at the end of the

previous reporting period for the sole purpose of

simplifying journal entries made during the new

period. Reversing entries are optional and are used

most often with accruals.

Let’s consider the following accrual adjusting

entry made by Dress Right.

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

July 31 Salaries Expense

Salaries Payable

Page 30

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

5,500

5,500

1-91

Reversing Entries

If reversing entries are used, the following reversing entry is

made on August 1, 2006. This entry reduces the salaries

payable account to zero and reduces the salaries expense

account by $5,500.

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Aug

Description

1 Salaries Payable

Salaries Expense

Salaries Expense

Bal. 7/31

10,500

5,500 Reverse

Bal.

5,000

Page 30

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

5,500

5,500

Salaries Payable

5,500 Bal. 7/31

Reverse 5,500

Bal.

1-92

End of Chapter 2

The Balance

Sheet and

Financial

Disclosures

3

Copyright © 2007 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

1-94

Learning Objectives

Describe the purpose of the balance sheet and

understand its usefulness and limitations.

1-95

The Balance Sheet

The purpose of the balance sheet is to report a

company’s financial position on a particular date.

Limitations:

The balance sheet does not

portray the market value of

the entity as a going concern

nor its liquidation value.

Resources such as

employee skills and

reputation are not recorded

in the balance sheet.

Usefulness:

The balance sheet describes

many of the resources a

company has available for

generating future cash flows.

It provides liquidity

information useful in

assessing a company’s

ability to pay its current

obligations.

It provides long-term

solvency information relating

to the riskiness of a

company with regard to the

amount of liabilities in its

capital structure.

1-96

Balance Sheet

Claims against

resources (Liabilities)

Resources

(Assets)

Remaining claims

accruing to owners

(Owners’ Equity)

1-97

Learning Objectives

Distinguish between current and noncurrent

assets and liabilities.

Identify and describe the various balance

sheet asset classifications.

1-98

FedEx Corporation

Balance Sheet

31-May

Assets are

probable

future

economic

benefits

obtained or

controlled by

a particular

entity as a

result of past

transactions

or events.

(In millions)

Assets:

Current assets:

Cash and cash equivalents

Receivables, less allowances

Spare parts, supplies, and fuel

Deferred income taxes

Prepaid expenses and other

Total current assets

Property and equipment, at cost:

Aircraft and related equipment

Package handling & ground support

equipment and vehicles

Computer & electronic equipment

Other

Less accumulated depreciation

Net property and equipment

Other long-term assets:

Goodwill

Prepaid pension cost

Intangible and other assets

Total other long-term assets

Total Assets

2004

$

2003

$

1,046 $

3,027

249

489

159

4,970 $

538

2,627

228

416

132

3,941

$

7,001 $

6,624

$

5,296

3,537

4,477

20,311

11,274

9,037

5,013

3,180

4,200

19,017

10,317

8,700

2,802

1,127

1,198

5,127

19,134 $

1,063

1,269

412

2,744

15,385

1-99

Current Assets

Current

Assets

Cash

Cash Equivalents

Short-term Investments

Receivables

Inventories

Prepayments

Will be converted

to cash or

consumed within

one year or the

operating cycle,

whichever is

longer.

Cash equivalents

include certain

negotiable items such

as commercial paper,

money market funds,

and U.S. treasury bills.

1100

Current Assets

Current

Assets

Cash

Cash Equivalents

Short-term Investments

Receivables

Inventories

Prepayments

Will be converted

to cash or

consumed within

one year or the

operating cycle,

whichever is

longer.

Cash that is restricted

for a special purpose

and not available for

current operations

should not be

classified as a current

asset.

Operating Cycle of a Typical Manufacturing

Company

Use cash to acquire raw materials

Convert raw materials to finished

product

Deliver product to customer

Collect cash from customer

1101

1102

Noncurrent Assets

Noncurrent

Assets

Not expected to

be converted to

cash or

consumed within

one year or the

operating cycle,

whichever is

longer

Investments and

Funds

Property, Plant, &

Equipment

Intangibles

Other

1103

Noncurrent Assets

Investments and Funds

1. Not used in the operations of

the business

2. Includes both debt and equity

securities of other

corporations, land held for

Property,

Plant and

Equipment

speculation,

noncurrent

receivables,

and cash set

1. Are

tangible, long-lived,

and

asideinfor

purposes

used

thespecial

operations

of the

business

2. Includes land, buildings,

equipment, machinery, and

furniture as well as natural

resources such as mineral

©

Intangible Assets

1. Used in the operations of

the business but have no

physical substance

2. Includes patents,

copyrights, and

franchises

Other Assets

3. Reported net of

1. Includes

long-term

accumulated

prepaid

expenses and

amortization

any noncurrent assets

not falling in one of the

other classifications

1104

Learning Objectives

Identify and describe the two balance sheet

liability classifications.

FedEx Corporation

Balance Sheet

31-May

(In milions)

Liabilities:

Current liabilities:

Current portion of long-term debt

Accrued salaries & employee benefits

Accounts payable

Accrued expenses

Total current liabilities

Long-term debt, less current portion

Other long-term liabilities

Deferred income taxes

Pension, postretirement healthcare

and other benefit obligations

Self-insurance accruals

Deferred lease obligations

Deferred gains, principally related to

aircraft transactions

Other liabilities

Total other long-term liabilities

Total liabilities

1105

2004

$

2003

750 $ 308

1,062

724

1,615

1,168

1,305

1,135

4,732

3,335

2,837

1,709

1,181

882

768

591

503

657

536

466

426

60

3,529

11,098

455

57

3,053

8,097

Liabilities are

probable

future

sacrifices of

economic

benefits

arising from

present

obligations of

a particular

entity to

transfer

assets or

provide

services to

other entities

as a result of

past

transactions

or events.

1106

Current Liabilities

Current

Liabilities

Obligations expected to be

satisfied through current

assets or creation of other

current liabilities within one

year or the operating cycle,

whichever is longer

Accounts Payable

Notes Payable

Accrued Liabilities

Current Maturities

of Long-Term Debt

1107

Long-term Liabilities

Long-Term

Liabilities

Obligations that

will not be

satisfied within

one year or

operating cycle,

whichever is

longer

Notes Payable

Mortgages

Bonds Payable

Pension Obligations

Lease Obligations

1108

FedEx Corporation

Balance Sheet

31-May

(In millions, except shares)

Common Stockholders' Investment:

Common stock, $.10 par value, 800 million

shares authorized, 300 million shares

issued for 2004 and 299 million shares

issued for 2003

Additional paid-in capital

Retained earnings

Accumulated other comprehensive loss

Less deferred compensation and treasury

stock at cost

Total common stockholders' investment

2004

$

$

2003

30 $

30

1,079

7,001

(46)

8,064

1,088

6,250

(30)

7,338

28

8,036 $

50

7,288

Shareholders’ Equity is the residual interest in the

assets of an entity that remains after deducting

liabilities.

1109

Shareholders’ Equity

Capital

Stock

Deferred

Compensation

Retained

Earnings

Treasury

Stock

Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income

1110

Learning Objectives

Explain the purpose of financial statement

disclosures.

1111

Disclosure Notes

Summary of

Significant

Accounting Policies

Subsequent Events

Noteworthy Events

and Transactions

Conveys valuable

information about the

company’s choices from

among various alternative

accounting methods.

A significant development

that takes place after the

company’s fiscal year-end

but

before theor

financial

Transactions

events

statements

are issued.

that are potentially

important to evaluating a

company’s financial

statements, e.g., related

parties, errors and

irregularities, and illegal

acts.

1112

Learning Objectives

Explain the purpose of management’s

discussion and analysis.

1113

Management Discussion and Analysis

Provides a biased but

informed perspective of

a company’s

operations, liquidity,

and capital resources.

Management’s Responsibilities

Preparing the financial

statements and other

information in the

annual report.

Maintaining and

assessing the

company’s internal

control procedures.

1114

1115

Learning Objectives

Explain the purpose of an audit and describe

the content of the audit report.

Auditors’ Report

Expresses the auditors’ opinion

as to the fairness of

presentation of the financial

statements in conformity with

generally accepted accounting

principles

Must comply with specifications

of the AICPA and the PCAOB

1116

Auditors’ Opinions

Unqualified

Qualified

Adverse

Disclaimer

1117

Issued when the financial

statements present fairly

the financial position,

results of operations, and

cash flows in conformity

Issued when there is an

with GAAP

exception that is not of

sufficient seriousness to

invalidate the financial

statements as a whole

Issued when the

exceptions are so serious

that a qualified opinion is

not justified

Issued when insufficient

information has been

gathered to express an

opinion

1118

Learning Objectives

Describe the techniques used by financial

analysts to transform financial information into

forms more useful for analysis.

1119

Using Financial Statement Information

Comparative Financial

Statements

Horizontal Analysis

Vertical Analysis

Ratio Analysis

Allow financial statement

users to compare year-toyear financial position,

results of operations, and

Expresses each item in

cash flows

the financial statements

as a percentage of that

Involves

expressing

each

same

item

in the financial

item in theof

financial

statements

another

statements

as a

year

(base amount)

percentage of an

appropriate

corresponding total, or

base amount, within the

Allows analysts to control

same year.

for size differences over

time and among firms

1120

Learning Objectives

Identify and calculate the common liquidity and

financing ratios used to assess risk.

1121

Liquidity Ratios

Current assets

Current ratio =

Current liabilities

Measures a company’s ability to satisfy its

short-term liabilities

Quick assets

Acid-test ratio

=

Current liabilities

Provides a more stringent indication of a

company’s ability to pay its current

liabilities

1122

Financing Ratios

Total liabilities

Debt to equity

=

ratio

Shareholders’ equity

Indicates the extent of reliance on

creditors, rather than owners, in providing

resources

Times interest

earned ratio

=

Net income + Interest

expense + Taxes

Interest expense

Indicates the margin of safety provided to

creditors

The Income

Statement and

Statement of

Cash Flows

4

Copyright © 2007 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

1124

Learning Objectives

Explain the difference between net income and

comprehensive income and how we report

components of the difference.

1125

Comprehensive Income

An expanded

version of income

that includes four

types of gains and

losses that

traditionally have

not been included

in income

statements.

1126

Other Comprehensive Income

Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 130

Comprehensive income includes traditional net income

and changes in equity from nonowner transactions.

1. Changes in the market value of securities available for sale

(described in Chapter 12).

2. Gains, losses, and amendment costs for pensions and other

postretirement plans (described in Chapter 17).

3. When a derivative is designated as a cash flow hedge is adjusted to

fair value, the gain or loss is deferred as a component of

comprehensive income and included in earnings later, at the same

time as earnings are affected by the hedged transaction (described in

Chapter 14).

4. Gains or losses from changes in foreign currency exchange rates

(discussed elsewhere in your accounting curriculum).

1127

Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income

In addition to reporting comprehensive income that

occurs in the current period, we must also report these

amounts on a cumulative basis in the balance sheet as

an additional component of shareholders’ equity.

FedEx Corporation

Balance Sheet

31-May

(In millions, except shares)

Common Stockholders' Investment:

Common stock, $.10 par value, 800 million

shares authorized, 300 million shares

issued for 2004 and 299 million shares

issued for 2003

Additional paid-in capital

Retained earnings

Accumulated other comprehensive loss

Less deferred compensation and treasury

stock at cost

Total common stockholders' investment

2004

$

$

2003

30 $

30

1,079

7,001

(46)

8,064

1,088

6,250

(30)

7,338

28

8,036 $

50

7,288

1128

Learning Objectives

Discuss the importance of income from

continuing operations and describe its

components.

1129

Income from Continuing Operations

Revenues

Expenses

Inflows of

resources

resulting

from

providing

goods or

services to

customers.

Outflows of

resources

incurred in

generating

revenues.

Gains and

Losses

Income Tax

Expense

Increases or

decreases in

equity from

peripheral or

incidental

transactions

of an entity.

Because of

its

importance

and size,

income tax

expense is a

separate

item.

Operating Income Versus Nonoperating

Income

Operating

Income

Nonoperating

Income

Includes revenues

and expenses

directly related to

the principal

revenuegenerating

activities of the

company

Includes gains and

losses and

revenues and

expenses related

to peripheral or

incidental

activities of the

company

1130

1131

Income Statement (Single-Step)

{

Proper Heading

Revenues

& Gains

Expenses

& Losses

{

{

MAXWELL GEAR COMPANY

Income Statement

For the Year Ended December 31, 2006

Revenues and gains:

Sales

Interest and dividends

Gain on sale of opearting assets

Total revenues and gains

Expenses and losses:

Cost of goods sold

Selling

General and administrative

Research and development

Interest

Loss on sale of investment

Income taxes

Total expenses & losses

Net income

$

$

573,522

26,400

5,500

605,422

302,371

47,341

24,888

16,300

6,200

8,322

80,000

$

485,422

120,000

1132

Income Statement (Multiple-Step)

{

Proper Heading

Gross

Profit

Operating

Expenses

Nonoperating

Items

{

{

{

MAXWELL GEAR CORPORATION

Income Statement

For the Year Ended December 31, 2006

Sales revenue

Cost of goods sold

Gross profit

Operating expenses:

Selling

$

General and administrative

Research and development

Operating income

Other income (expense):

Interest and dividend revenue $

Gain on sale of operating assets

Interest expense

Loss on sale of investments

Income before income taxes

Income tax expense

Net income

$

47,341

24,888

16,300

573,522

302,371

271,151

88,529

182,622

26,400

5,500

(6,200)

(8,322)

$

17,378

200,000

80,000

120,000

1133

Learning Objectives

Describe earnings quality and how it is

impacted by management practices to

manipulate earnings.

1134

Earnings Quality

Earnings quality refers to

the ability of reported

earnings to predict a

company’s future.

The relevance of any

historical-based financial

statement hinges on its

predictive value.

1135

Manipulating Income and Income Smoothing

“Most managers prefer to report earnings that follow a

smooth, regular, upward path.”1

Two ways to manipulate income:

1. Income shifting

2. Income statement

classification

1

Bethany McLean, “Hocus-Pocus: How IBM Grew 27% a Year,” Fortune, June 26, 2000, p. 168.

1136

Learning Objectives

Discuss the components of operating and

nonoperating income and their relationship to

earnings quality.

1137

Nonoperating Income and Earnings Quality

Gains and losses from the sale of operational

assets and investments often can significantly

inflate or deflate current earnings.

Example

As the stock market boom reached its

height late in the year 2000, many

companies recorded large gains from

sale of investments that had

appreciated significantly in value.

How should

those gains be

interpreted in

terms of their

relationship to

future

earnings? Are

they transitory

or permanent?

1138

Separately Reported Items

Reported separately, net of taxes:

Discontinued

operations

Income from continuing operations

before income taxes and

extraordinary items

Income tax expense

Income from continuing operations

before extraordinary items

Discontinued operations (net of $xx

in taxes)

Extraordinary items (net of $xx in

taxes)

Net Income

Extraordinary

items

$ xxx

xx

xxx

xx

xx

$ xxx

A third item,

the cumulative

effect of a

change in

accounting

principle, was

eliminated

from separate

reporting by a

1139

Intraperiod Income Tax Allocation

Income Tax Expense must be associated with

each component of income that causes it.

Show Income Tax

Expense related to

Income from

Continuing

Operations.

Report effects of

Discontinued Operations

and Extraordinary Items

NET OF RELATED

INCOME TAXES.

1140

Learning Objectives

Define what constitutes discontinued

operations and describe the appropriate

income statement presentation for these

transactions.

Discontinued Operations

A discontinued operation is the sale or

disposal of a component of an entity.

A component comprises operations and

cash flows that can be clearly

distinguished, operationally and for

financial reporting purposes, from the rest

of the entity.

A component could include:

Reportable segments

Operating segments

Reporting units

Subsidiaries

Asset groups

1141

1142

Discontinued Operations

Report results of operations separately if two

conditions are met:

The operations and

cash flows of the

component have been

(or will be) eliminated

from the ongoing

operations.

The entity will not have

any significant

continuing involvement

in the operations of the

component after the

disposal transaction.

1143

Discontinued Operations

Reporting for Components Sold

Operating income or

loss of the component

from the beginning of

the reporting period to

the disposal date.

Gain or loss on the

disposal of the

component.

Reporting for Components Held For Sale

Operating income or

loss of the component

from the beginning of

the reporting period to

the end of the reporting

period.

An “impairment loss” if

the carrying value of

the assets of the

component is more

than the fair value

minus cost to sell.

Discontinued Operations Example

1144

During the year, Apex Co. sold an

unprofitable component of the company. The

component had a net loss from operations

during the period of $150,000 and its assets

sold at a loss of $100,000. Apex reported

income from continuing operations of

$128,387. All items are taxed at 30%.

How will this appear in the income

statement?

Discontinued Operations Example

Computation of Loss from Discontinued Operations

(Net of Tax Effect):

Loss from discontinued operations

Less: Tax benefit ($150,000 × 30%)

Net loss

$

Loss on disposal of assets

Less: Tax benefit ($100,000 × 30%)

Net loss

$

$

$

(150,000)

45,000

(105,000)

(100,000)

30,000

(70,000)

1145

Discontinued Operations Example

Income Statement Presentation:

Income from continuing operations

Discontinued operations:

Loss from operations of discontinued

component (net of tax benefit of

$45,000)

Loss on disposal of discontinued

component (net of tax benefit of

$30,000)

Net loss

$ 128,387

(105,000)

(70,000)

$ (46,613)

1146

1147

Learning Objectives

Define extraordinary items and describe the

appropriate income statement presentation for

these transactions.

Extraordinary Items

Material

events or

transactions

Unusual in nature

Infrequent in occurrence

Reported net of related

taxes

1148

Extraordinary Items Example

During the year, Apex Co. experienced a

loss of $75,000 due to an earthquake at one

of its manufacturing plants in Nashville.

This was considered an extraordinary item.

The company reported income before

extraordinary item of $128,387. All gains

and losses are subject to a 30% tax rate.

How would this item appear in the

income statement?

1149

1150

Extraordinary Items Example

Computation of Loss from Extraordinary Item (Net of

Tax Effect):

Extraordinary Loss

Less: Tax Benefits

($75,000 × 30%)

Net Loss

$ (75,000)

22,500

$ (52,500)

Income Statement Presentation:

Income before extraordinary item

Extraordinary Loss:

Earthquake loss

(net of tax benefit of $22,500)

Net income

$ 128,387

(52,500)

$ 75,887

Unusual or Infrequent Items

Items that are material and are either

unusual or infrequent—but not both—

are included as a separate item in

continuing operations.

1151

1152

Accounting Changes

Type of Accounting

Change

Definition

Change in Accounting

Principle

Change from one GAAP method

to another GAAP method

Change in Accounting

Estimate

Revision of an estimate

because of new information or

new experience

Preparation of financial

statements for an accounting

entity other than the entity that

existed in the previous period

Change in Reporting

Entity

1153

Learning Objectives

Describe the measurement and reporting

requirements for a change in accounting

principle.

Change in Accounting Principle

Occurs when changing from one GAAP

method to another GAAP method

For example, a change from LIFO to FIFO

Voluntary changes in accounting

principles are accounted for

retrospectively by revising prior years’

financial statements.

Changes in depreciation, amortization, or

depletion methods are accounted for the

same way as a change in accounting

estimate.

1154

1155

Learning Objectives

Explain the accounting treatments of changes

in estimates and correction of errors.

Change in Accounting Estimate

Revision of a

previous accounting

estimate

Use new estimate in

current and future

periods

Includes treatment for

changes in depreciation,

amortization, and

depletion methods

1156

1157

Change in Accounting Estimate Example

On January 1, 2003, we purchased

equipment costing $30,000, with a useful

life of 10 years and no salvage value.

During 2006, we determine that the

remaining useful is 5 years (8-year total

life). We use straight-line depreciation.

Compute the revised depreciation

expense for 2006.

1158

Change in Accounting Estimate Example

Asset cost

Accumulated depreciation

12/31/05 - ($3,000 × 3 years)

Remaining to be depreciated

Remaining useful life

Revised annual depreciation

GENERAL JOURNAL

$

30,000

$

(9,000)

21,000

÷ 5 years

4,200

Page: 180

Credit

Description

PR

Debit

Record

depreciation

expense

of

$4,200

for

Depreciation Expense

4,200

2006 andDepreciation

subsequent years.

Accumulated

4,200

Date

Prior Period Adjustments

Corrections

of errors from a

previous period

Appear

in the Statement of

Retained Earnings as an

adjustment to beginning

retained earnings

Must

show the adjustment

net of income taxes

1159

1160

Prior Period Adjustments Example

While reviewing the depreciation entries for

2002-2007, the controller found that in 2006

depreciation expense was incorrectly debited

for $150,000 when in fact it should have been

debited $125,000. (Ignore income taxes.)

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

12/31/06 Depreciation Expense

Accumulated Depreciation

PR

Debit

Page: 180

Credit

150,000

150,000

Prepare the necessary journal entry in 2007 to

correct this prior period error.

1161

Prior Period Adjustments Example

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

PR

Debit

Page: 180

Credit

2007 Entry

Accumulated Depreciation

Retained Earnings

25,000

25,000

1162

Learning Objectives

Define earnings per share (EPS) and explain

required disclosures of EPS for certain income

statement components.

1163

Earnings Per Share Disclosure

One of the most widely used ratios is earnings per

share (EPS), which shows the amount of income

earned by a company expressed on a per share basis.

Basic EPS

Net income less preferred

dividends

Weighted-average number

of common shares

outstanding for the period

Diluted EPS

Reflects the potential dilution

that could occur for companies

that have certain securities

outstanding that are convertible

into common shares or stock

options that could create

additional common shares if the

options were exercised.

1164

Earnings Per Share Disclosure

Report EPS data separately for:

1. Income from Continuing Operations

2. Separately Reported Items

a) Discontinued Operations

b) Extraordinary Items

3. Net Income

1165

Learning Objectives

Describe the purpose of the statement of cash

flows.

1166

The Statement of Cash Flows

Provides relevant information about a

company’s cash receipts and cash

disbursements.

Helps investors and creditors to assess

future net cash flows

liquidity

long-term solvency.

Required for each income statement period

presented.

1167

Learning Objectives

Identify and describe the various classifications

of cash flows presented in a statement of cash

flows.

1168

Operating Activities

Inflows from:

Sales to customers.

Interest and dividends

received.

+

Outflows to:

Purchase of inventory.

Salaries, wages, and other

operating expenses.

Interest on debt.

Income taxes.

_

Cash

Flows

from

Operating

Activities

1169

Direct and Indirect Methods of Reporting

Two Formats for Reporting Operating Activities

Direct Method

Indirect Method

Reports the cash

effects of each

operating activity

Starts with

accrual net

income and

converts to cash

basis

1170

Investing Activities

Inflows from:

Sale of long-term assets used in

the business.

Sale of investment securities

(stocks and bonds).

Collection of nontrade

receivables.

+

Outflows to:

Purchase of long-term assets

used in the business.

Purchase of investment

securities (stocks and bonds).

Loans to other entities.

_

Cash

Flows

from

Investing

Activities

1171

Financing Activities

Inflows from:

Sale of shares to owners.

Borrowing from creditors

through notes, loans,

mortgages, and bonds.

+

Outflows to:

Owners in the form of dividends

or other distributions.

Owners for the reacquisition of

shares previously sold.

Creditors as repayment of the

principal amounts of debt.

_

Cash

Flows

from

Financing

Activities

1172

Noncash Investing and Financing Activities

Significant investing and financing

transactions not involving cash also

are reported.

Acquisition of equipment (an investing activity) by

issuing a long-term note payable (a financing

activity).

Cash and

Receivables

Insert Book Cover

Picture

7

Copyright © 2007 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.

1174

Cash

Coins and

currency

Petty cash

Cashier’s checks

Certified checks

Money orders

Amounts on

deposit with

financial

institutions

1175

Cash Equivalents

Items very near cash but

not in negotiable form

Money market

funds

Treasury bills

Commercial

paper

Restricted Cash and

Compensating Balances

Restricted Cash

Management’s intent to use a certain amount

of cash for a specific purpose – future plant

expansion, future payment of debt.

Compensating Balance

Minimum balance that must be maintained

in a company’s account as support for

funds borrowed from the bank.

1176

1177

Learning Objectives

Distinguish between the gross and net

methods of accounting for cash discounts

Accounts Receivable

Amounts due from

customers for credit sales.

Credit sales require:

Maintaining a separate

account receivable for each

customer.

Accounting for bad debts

that result from credit

sales.

1178

1179

Cash Discounts

Increase sales.

Cash discounts . . .

Encourage early

payment.

Increase likelihood of

collections.

1180

Cash Discounts

2/10,n/30

Discount

Percent

Number of

Days

Discount is

Available

Otherwise,

Net (or All)

is Due

Credit

Period

1181

Cash Discounts

Sales are

recorded at the

invoice

amounts.

Gross

Method

Sales discounts

are recorded if

payment is

received within

the discount

period.

1182

Cash Discounts

Net

Method

Sales are recorded at the Sales discounts forfeited

invoice amount less the

are recorded if payment

discount.

is received after the

discount period.

1183

Learning Objectives

Describe the accounting treatment for

merchandise returns.

Sales Returns and Allowances

Sales Returns

Sales Allowances

Merchandise

returned by a

customer to a

supplier.

A reduction in

the cost of

defective

merchandise.

1184

Sales Returns and Allowances

On June 1, a customer of LarCo returns

$750 of merchandise. The merchandise

had been purchased on account and the

customer had not yet paid. LarCo uses

the periodic method to account for

inventory.

Record the journal entry for the return of

merchandise.

1185

1186

Sales Returns and Allowances

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Jun

Description

1 Sales Returns and Allowances

Post.

Ref.

Page 56

Debit

Credit

750

Accounts Receivable

Sales Returns and Allowances is a contra

account that reduces Sales Revenue in the

current accounting period.

750

1187

Learning Objectives

Describe the accounting treatment of

anticipated uncollectible accounts receivable.

Uncollectible Accounts Receivable

Bad debts result from credit customers who

are unable to pay the amount they owe,

regardless of continuing collection efforts.

PAST DUE

1188

Uncollectible Accounts Receivable

In conformity with the matching principle,

bad debt expense should be recorded in

the same accounting period in which the

sales related to the uncollectible account

were recorded.

1189

1190

Uncollectible Accounts Receivable

Most businesses record an estimate of the

bad debt expense by an adjusting entry

at the end of the accounting period.

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

Dec. 31 Bad Debt Expense

Allowance for Uncollectible

Accounts

Page 78

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

####

####

1191

Uncollectible Accounts Receivable

Normally classified as

a selling expense and

closed at year-end.

Contra asset account to

Accounts Receivable.

GENERAL JOURNAL

Date

Description

Dec. 31 Bad Debt Expense

Allowance for Uncollectible

Accounts

Page 78

Post.

Ref.

Debit

Credit

####

####

Allowance for Uncollectible Accounts

1192

Accounts Receivable

Less: Allowance for Uncollectible Accounts

Net Realizable Value

Net realizable value is the amount of the

accounts receivable that the business

expects to collect.

1193

Learning Objectives

Describe the two approaches

to estimating bad debts.

1194

Estimating Bad Debts

Income Statement Approach

Balance Sheet Approach

Composite Rate

Aging of Receivables

PAST DUE

Income Statement Approach

Focuses on past credit sales to make

estimate of bad debt expense.

Emphasizes the matching principle by

estimating the bad debt expense associated

with the current period’s credit sales.

1195

Income Statement Approach

Bad debts expense is

computed as follows:

Current Period Credit Sales

× Bad Debt %

= Estimated Bad Debts Expense

1196

1197

Balance Sheet Approach

Focuses on the collectibility of accounts

receivable to make the estimate of uncollectible

accounts.

Involves the direct computation of the desired

balance in the allowance for uncollectible

accounts.

1198

Balance Sheet Approach

Composite Rate

Compute the desired balance in the Allowance for

Uncollectible Accounts.

Year-end Accounts Receivable

× Bad Debt %

Bad Debts Expense is computed as:

1199

Now, let’s

look at the

accounts

receivable

aging

approach!

Balance Sheet Approach

Aging of Receivables

Year-end Accounts Receivable is

broken down into age classifications.

Each age grouping has a different

likelihood of being uncollectible.

Compute desired uncollectible amount.

Compare desired uncollectible amount

with the existing balance in the

allowance account.

1200

1201

Balance Sheet Approach

Aging of Receivables

At December 31, 2006, the receivables for

EastCo, Inc. were categorized as follows:

EastCo, Inc.

Schedule of Accounts Receivable by Age

Days Past Due

Current

1 - 30

31 - 60

Over 60

December 31, 2006

Accounts

Estimated

Estimated

Receivable Bad Debts Uncollectible

Balance

Percent

Amount

$

$

45,000

15,000

5,000

2,000

67,000

1% $

3%

5%

10%

$

450

450

250

200

1,350

1202

Balance Sheet Approach

Aging of Receivables

EastCo’s unadjusted balance

in the allowance account is

$500.

Allowance for

Uncollectible

Accounts

500

Per the previous computation,

the desired balance is $1,350.