UNCESCR General Comment 14 on Right to Health

advertisement

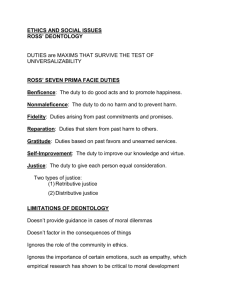

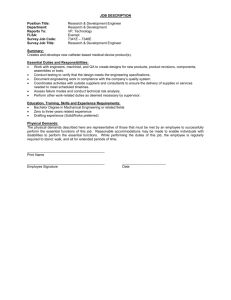

ESRC Seminar ‘Theoretical Perspectives on Global Health and Human Rights’ 19-20 April 2007, University of Liverpool The Minimum Core, South African Socioeconomic Rights Jurisprudence and the Right to Health: Theoretical and Practical Implications by Dr. Lisa Forman Post-Doctoral Fellow Canadian Institutes of Health Research Comparative Program on Health and Society University of Toronto Email: lisa.forman@utoronto.ca 1 Presentation 1) Objections to the Right to Health 2) International Human Rights Conceptualization 3) South African Jurisprudence 4) Implications for Theory and Practice 2 1. Objections to the Right to Health Right to health is not universal Right to health is unrealistic Rights would make zero-sum claim on limited resources Negative/positive distinction between civil and social rights Negative rights require resources and inaction to be realized Positive rights require little resources and state inaction to be realized Legislatures not courts should decide positive rights Objections found arguments that social rights are rather political, aspirational or programmatic rights 3 Inaccuracy of the Positive/Negative Distinction Distinction has philosophical roots in Kant and Berlin’s ideas about positive and negative duties and liberties Positive/negative contracted to mean action/inaction & resource-intensive/resource-free Contraction inaccurately reflects reality My right to free expression requires state non-interference But ensuring non-interference requires active legal and policy process ‘Negative’ rights therefore require action and resources 4 All Rights Impose Costs and Multiple Duties All rights require vigorous state action and have budgetary implications Civil rights impose considerable costs (Holmes and Sunstein, 2001, Hunt, 1996) Henry Shue (1980): all rights impose three kinds of duties: duties to avoid depriving, duties to protect from deprivation, duties to aid the deprived Idea enters international human rights interpretations (Asbjorn Eide, 1987): duty to respect (not to obstruct) positive duty to protect (ensure others don’t obstruct) positive duty to fulfill (provide) 5 Threat is of Persistent Bias Continuum from ostensibly negative (don’t obstruct) to ostensibly positive (provide) Paradigm may nonetheless suggest that civil rights tend towards duties to respect; social rights towards duty to fulfill However duties to respect may require resources as much as duty to fulfill and realizing social rights may not require providing commodities but preventing their deprivation Designing institutions to protect subsistence need not be more “positive,” unrealistic or unaffordable than designing programs to control violent crime: “Neither looks simple, cheap or “negative”” (Henry Shue, 1980) 6 Ideological Roots of Contestation Positive/negative distinction reflects liberal conception of non-interventionist state protecting individual freedom and private property If civil rights and property protection require resources and state action even night-watchman state is interventionist and redistributive albeit favouring private property not the poor Ascendancy of liberalism poses challenges of countering ideological resistance to right to health Pragmatic and ideological objections may have blurred for judges and politicians 7 Presentation 1) Objections to the Right to Health 2) International Human Rights Conceptualization 3) South African Jurisprudence 4) Implications for Theory and Practice 8 A Post-Ontological Era for the International Right to Health International Constitution of the World Health Organization (1946) Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) article 25(1) Covenant on Economic Social and Cultural Rights (1966) article 12 Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) article 24(1) Convention on Elimination of Racial Discrimination (1965) article 5(e)(iv) Convention on Elimination of Discrimination against Women (1979) articles 11(1)(f) and 12 Convention on the Protection of the Rights of Migrants Workers (2002) article 28 Regional European Social Charter (1961) article 11 African Charter of Human and People’s Rights (1981) article 16 American Protocol of San Salvador (1988) article 10 Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam (1990) article 17 Ratification of Treaties with Health Rights 200 150 100 192 183 170 153 50 0 Economic and Social Rights Covenant Racial Discrimination Covenant Women's Covenant Children's Covenant 9 Source: UN OHCHR (2006) Expert Interpretations of the Right to Health In Social Right’s Covenant, states recognizes everyone’s right to highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (article 12) However Covenant limits state duties to progressive realization to the maximum of available resources (article 2.1) Expert interpretations considerably advanced scope of entitlement and duties under social rights and of right to health especially UNCESCR General Comments 3 and 14 Progressive realization places immediate obligations on states and requires effective movement towards full realization through duties to respect, protect and fulfil Social rights contain minimum essential levels Social Rights Covenant indicates that rights can only be limited so far as compatible with their nature” (article 4) and acts aimed at destroying its rights were not permitted (article 5) Idea of minimum core inherent to the basic value that human rights places on human dignity, worth and life 10 UNCESCR General Comment 3 on State Obligations (1994) A state has minimum core obligations to ensure at the very least minimum essential levels of each right including essential primary health care If any significant number of individuals were deprived of essential primary health care, a state would be seen as prima facie, failing to discharge its obligations under the Covenant A government could only justify non-compliance with minimum core obligations by demonstrating every effort to use all resources available to satisfy these obligations as a matter of priority If the Covenant “were to be read in such a way as not to establish such a minimum core obligation, it would be largely deprived of its raison d'être” 11 UNCESCR General Comment 14 on Right to Health (2000) Irrespective of development levels, right to health contains essential elements such available, accessible, appropriate and good quality health care facilities, goods and services Drawing from ICPD and Alma-Ata, core obligations include at least : non-discriminatory access to health facilities, goods and services, especially for vulnerable or marginalized access to minimum essential food, basic shelter, housing and sanitation, and water essential drugs as defined by WHO equitable distribution of all health facilities, goods and services national public health strategy and plan of action addressing health concerns of all Committee argues core duties are non-derogable and noncompliance cannot be justified under any circumstances 12 Implications of Core Core is rights-based approach to deprivation If each person has inherent dignity and equal worth, significant deprivation of basic needs should be viewed as major human rights concern Meeting basic needs must take temporal and resource priority in realization of right to health Government must show deprivation is due to incapacity, not unwillingness Core as protection against competing political and economic priorities, inadequate resource allocations to health, corruption and uncaring government Core as a limit to unreasonable incursions into people’s basic needs by political and commercial actors Not unreasonable duties to place on poor countries Apply to rich country action domestically and internationally 13 Content of the Core? General Comment 14 only indicates that core is consistent with essential primary health care and includes essential drugs Core as guideposts for countries (Brigit Toebes, 1999) Variable content but “core” idea maintains that social rights cannot be limited to any extent Reflects central idea that rights require governments to prioritize meeting the “minimum decencies of citizenship in the modern world” for the poor (Albie Sachs, 1993) 14 Core Creates Normative Hierarchy Core advances normative hierarchy within right to health Idea has implications for balancing right to health against governmental claims of scarcity or competing private interests Core also has implications for institutions causing systemic restrictions of basic needs, eg WTO TRIPS agreement Core right to essential medicines suggests that TRIPS restriction on medicines and limited justification should alter how it is formulated, implemented and interpreted in poor countries 15 Presentation 1) Objections to the Right to Health 2) International Human Rights Conceptualization 3) South African Jurisprudence 4) Implications for Theory and Practice 16 South African Constitution Act 90 of 1996 Constitution includes enforceable socioeconomic rights to health care services, food, water, social security, housing and education Transformative document with pervasive commitment to open, accountable and responsive democracy based on human dignity, equality and freedom Constitutional entrenchment of state duties to “respect, protect, promote and fulfil all rights” (section 7.1) 17 Section 27: Everyone’s Right to Access Health Care Services (1a) Everyone has the right to have access to health care services, including reproductive health care (2) State must take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve progressive realisation (3) No one may be refused emergency medical treatment 18 Constitutional Certification Judgment (1996) Court rejected objections to constitutional entrenchment of socioeconomic rights All judicial review carries budgetary implications and much makes social policy Enforcing social and economic rights not so different a task as to breach separation of powers. Socioeconomic rights were “at least to some extent, justiciable,” and at the very minimum could be “negatively protected from improper invasion” 19 Soobramoney v Minister of Health (1996) Hospital’s denial of dialysis to very sick man did not breach section 27 Social rights depended on resources and an unqualified obligation to meet even basic needs could not be filled Given difficult decisions court would be “slow to interfere with rational decisions taken in good faith by the political organs and medical authorities whose responsibility it was to deal with such matters” 20 Grootboom v Government of RSA (2000) Squatters evicted off government land without alternative shelter Court rejected minimum core arguments of amici Court noted UNESCR Committee not specified minimum core on housing and argued that it lacked competence and information to determine content Reasonableness standard adopted as standard of compliance Reasonableness determined case by case, in social and historical context of poverty, and constitutional context of commitment to equality, dignity and freedom State’s negative duty not to prevent right of access to adequate housing State’s positive duty to act reasonably to provide basic necessities of life to those lacking Positive duty not absolute or unqualified but assessed by standard of reasonableness 21 Elements of the Reasonableness Standard Primarily requires comprehensive plans dealing with all needs Unreasonable to exclude significant segment of society Focus must be on needs of poor dependent on state for basic necessities Focus on urgent and desperate needs: “If the measures, though statistically successful, fail to respond to the needs of those most desperate, they may not pass the test.” [44] State can’t do more than resources permit but state must give adequate budgetary support to social rights and plan, budget and monitor to try meet all needs 22 Implications of Grootboom… Case hailed as seminal internationally but extensively criticized nationally for rejecting core Reasonableness standard seen not as individual entitlement but administrative review requiring sensible priority (Sunstein, 2001, Bilchitz, 2002) Potential for immediate or tangible benefit to poor litigants seen as limited (Fitzpatrick and Slye, 2003) Raised questions whether reasonableness adequately substituted for the core, and whether it relieved deprivation 23 AIDS Policy Puts Reasonableness Standard to the Test Government resolutely refused and obstructed antiretroviral (ARV) medicines in public sector President Mbeki had adopted AIDS denialism: disputes causal link between HIV and AIDS and sees ARV as toxic and fatal South Africa’s AIDS pandemic is one of largest in the world 5 600 000 people infected (13 percent of population) 365 000 people dying per year, over 1000 a day Mass orphaning 80-90 000 children maternally infected each year 24 Contestation of Mother to Child Transmission Policy Social protest over government delay and refusal on drugs to prevent mother to child transmission (MTCT) Social groups sue arguing breach of section 27 Government defends approach given drug safety and efficacy and program costs Government strongly contests constitutionality of judicial review of health policy or strong judicial orders Court’s willingness to enforce positive duties put to test 25 Minister of Health v Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) (2002) Court found government policy unreasonably denied lifesaving drug to children born to mostly indigent mothers dependent on state for health care Court affirmed constitutional authority to review health policy and to make mandatory and supervisory orders Rejected right to minimum core without resource limits citing institutional incapacity and democratic considerations Suggestion that case dealt with negative not positive duty Court declared government’s responsibility to devise and implement a comprehensive MTCT program within available resources Ordered government to without delay: remove restrictions on drug; make it available in public sector; provide for counsellor training; take reasonable measures to extend testing and counselling facilities throughout public sector 26 Presentation 1) Objections to the Right to Health 2) International Human Rights Conceptualization 3) South African Jurisprudence 4) Implications for Theory and Practice 27 Theoretical Implications of Reasonableness standard Reasonableness standard may not effectively guide realization No temporal priorities to guide progressive realization (Roux, 2002) No definition of ‘urgency,’ ‘desperation;’ ‘poor and vulnerable’ (Liebenberg, 2002) No substantive content read into section 27 Problematic if reasonableness permits limitless restrictions But focus on basic health needs may approximate core Court has disregarded resource implications in egregious dignity impacts (TAC, Grootboom and Khosa) Reasonableness therefore largely consistent with international human rights law 28 Practical Outcomes of Reasonableness Standard Grootboom changed policy frameworks on housing for those in crisis TAC fundamentally altered national treatment policy National MTCT program is now in > 80% clinics 16 228 babies born to HIV+ mothers tested negative (82%) (MoH, 2007) National Treatment Program introduced TAC secured a critical health service for poor and prioritized health needs of poor against competing governmental priorities The right and enforcement conferred a powerful social claim for stigmatized population However significant differences in implementation suggest need for attention to remedial orders and perhaps supervisory jurisdiction 29 Positive/Negative Characterizations Approach shows justiciability of social rights and positive duties Undermines many traditional objections But cautious enforcement of positive duties reifies ideological objections and sharp distinctions Positive/negative does not necessarily equate to action/inaction or resource-heavy/resource-light It may obscure analytical approach to rights and remedies Need to shift to assessing rights from perspective of what needs to be done rather than working within unhelpful categorical straitjackets 30 Conclusion South African right’s legal force contingent on judicial willingness to enforce Choices by judiciary are ideologically motivated by deeper conceptions of the appropriate role of law and the state Right to health must target legal cultures and legal education that perpetuate paradigms on social rights Litigation without social action has limited force Rights assume power through social internalization as individual entitlements and collective norms demanding political priorities and legal protection Combination of legal and social strategies through rights discourse, advocacy, social mobilization and litigation may enable right to health to address global health inequalities and place reasonable limits on politics and economics in service of the health interests of the poor 31