Greek_Reading_List_Notes

advertisement

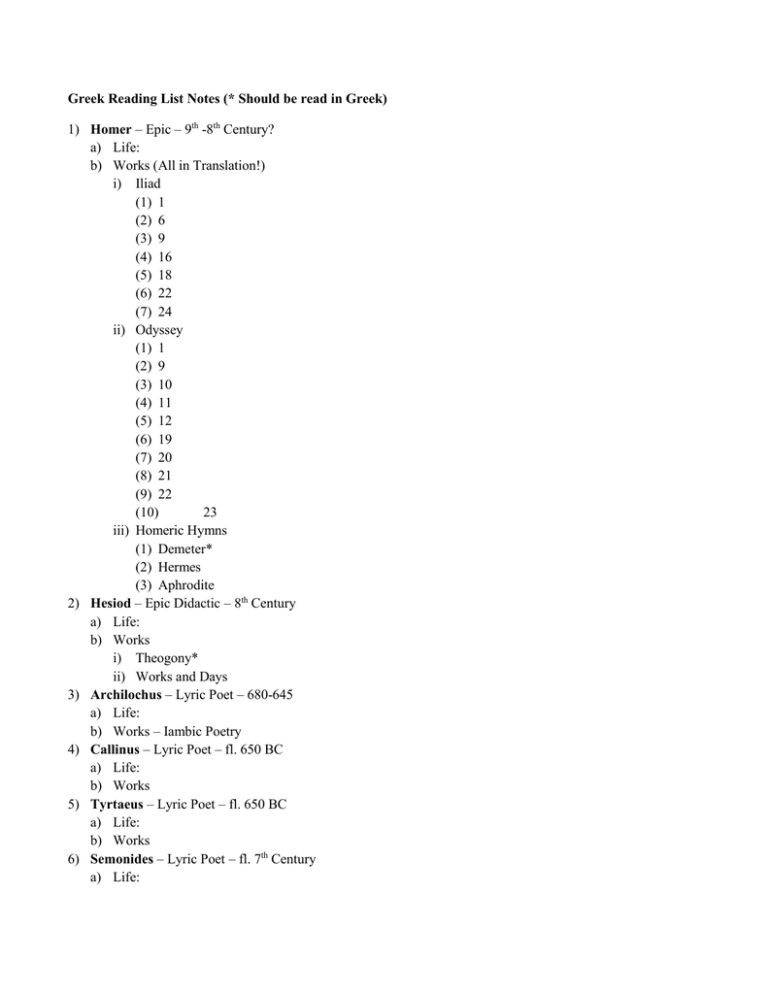

Greek Reading List Notes (* Should be read in Greek) 1) Homer – Epic – 9th -8th Century? a) Life: b) Works (All in Translation!) i) Iliad (1) 1 (2) 6 (3) 9 (4) 16 (5) 18 (6) 22 (7) 24 ii) Odyssey (1) 1 (2) 9 (3) 10 (4) 11 (5) 12 (6) 19 (7) 20 (8) 21 (9) 22 (10) 23 iii) Homeric Hymns (1) Demeter* (2) Hermes (3) Aphrodite 2) Hesiod – Epic Didactic – 8th Century a) Life: b) Works i) Theogony* ii) Works and Days 3) Archilochus – Lyric Poet – 680-645 a) Life: b) Works – Iambic Poetry 4) Callinus – Lyric Poet – fl. 650 BC a) Life: b) Works 5) Tyrtaeus – Lyric Poet – fl. 650 BC a) Life: b) Works 6) Semonides – Lyric Poet – fl. 7th Century a) Life: b) Works – Iambic Poetry 7) Alcman – Lyric Poet – 7th Century a) Life: b) Works – Choral Lyric 8) Mimnermus – Elegaic Poet – fl. 630-600 BC a) Life: b) Works 9) Solon – Politican and Poet – 638-558 BC a) Life: b) Works 10) Stesichorus – Lyric Poet – 640-555 BC a) Life: b) Works – Choral Lyric 11) Sappho – Lyric Poetess – 620?-570 BC a) Life: b) Works 12) Alcaeus – Lyric Poet – 620-? a) Life: b) Works 13) Ibycus – Lyric Poet – 6th Century a) Life: b) Works 14) Anacreon – Lyric Poet – 570-488 BC a) Life: b) Works 15) Xenophanes – Philosopher and Poet – 570-475 BC a) Life: b) Works 16) Phocylides – Lyric Poet – 560?-? BC a) Life: b) Works 17) Demodocus – Lyric Poet a) Life: b) Works 18) Theognis – Elegaic Poet – fl. 6th Century a) Life: b) Works 19) Hipponax – Iambic Poet – fl. 540 BC a) Life: b) Works 20) Simonides – Lyric Poet – 556-468 BC a) Life: b) Works 21) Pratinas –Lyric Poet – fl.500 a) Life: b) Works 22) Timocreon – Lyric Poet – fl. 480 BC a) Life: b) Works 23) Corinna – Lyric Poet – fl. 6th Century a) Life: b) Works 24) Bacchylides – Lyric, Epinician – fl. 5th Century a) Life: b) Works 25) Praxilla – Lyric Poet – fl. 5th Century a) Life: b) Works 26) Carmina Popularia (Check Campbell) 27) Scholia (Check Campbell) 28) Aeschylus – Tragedy 525–456 BC a) Life: b) Works i) Persians ii) Promethus Bound iii) Supplians iv) Seven Against Thebes v) Agamemnon* vi) Libation Bearers* vii) Eumenides* 29) Pindar – Lyric, Epinician – 522-443 BC a) Life: b) Works i) Olympian 1* ii) Olympian 7* iii) Pythian 1* iv) Pythian 2-5 v) Isthmian 2 30) Sophocles – Tragedy – 497-406 BC a) Life: b) Works i) Antigone* ii) Oedipus Tyrannus* iii) Oedipus at Colonus iv) Ajax v) Philoctetes vi) Electra vii) Trachiniae 31) Herodotus – History – 484-425? BC a) Life: b) The Histories i) 1* ii) 2 iii) 3 iv) 4 v) 5 vi) 6 vii) 7* viii) 8 ix) 9 32) Euripides – Tragedy – 480?-406 BC a) Life: b) Works: i) Medea* ii) Bacchae* iii) Hippolytus* iv) Alcestis v) Hercules Furens vi) Troades vii) Ion 33) Thucydides – History – 460?-395 BC a) Life: b) History (all in translation i) 1* ii) 2.34-65* iii) 3 iv) 4 v) 5 vi) 6* vii) 7* 34) Lysias – Oratory – 445-380? BC a) Life b) Works i) I* On the Murder of Eratosthenes ii) XII Against Eratosthenes 35) Aristophanes – Old Comedy – 446-386 BC a) Life: b) Works: i) Acharnians* ii) Clouds* iii) Wasps iv) Birds v) Lysistrata vi) Frogs vii) Plutus 36) Xenophon – Philosophy, History – 430-354 BC a) Life: b) Works i) Anabasis 1 ii) Oeconomicus iii) Constitution of the Athenians 37) Plato – Philosophy – 428-348 a) Life: b) Works i) Apology of Socrates* ii) Symposium* iii) Crito iv) Phaedrus v) Ion vi) Euthyphro (1) Socrates, before his trial, runs into Euthyphro, who is currently prosecuting his own father for murder. Euthyphro’s father had killed a man by tying him up and leaving him in a ditch, and Euthyphro is accused of impiety for taking on the prosecution of his own father. In the discussion which follows, Socrates attempts to get a definition of piety and impiety. He makes the distinction that piety is not pious because the gods approve of it, but the gods approve of piety because it is good. He ties Euthyphro in a logical knot, and when the young man attempts to leave he leaves him with the biting remark: “If you did not know what piety is, it is unthinkable that you would prosecute your own father. I am certain you know what piety is and what is not.” vii) Republic (10*) (1) Socrates and Co. (Thrasymachus, Glaucon, and Adimantus primarily) begin a discussion at the home of Polemarchus. The discussion arises from a chance conversation with P’s aged father Cephalus, who asserts that old age is no burden, but that he is concerned with tales about the end of life that only the just attain blessedness (interesting convergence with Er in book 10). Cephalus, however, leaves to sacrifice and leaves the younger men to their discussion. The main argument is between Thrasymachus, who asserts that justice is determined by those in power, while Socrates argues that justice, not injustice, is more profitable than injustice. Thrasymachus is not convinced, but falls silent. (2) Glaucon and Adimantus take up Thrasymachus’ argument, positing an injust man who seems just and a just man who seems unjust. Which, he asks, is the more blessed? Socrates begins by putting forth a city, and that each man in it must depend on and trade with others – for the skilled craftsman is more productive than the jack of all trades. Thus the city requires a “guardian” whose sole job and skill is to protect the city. This person will require a special education, and must especially be shielded from the notion that the God(s) can be the source of evil, untruth, or injustice. Thus some of Homer and the Tragedians (esp. Aeschylus) may need to be banished. (3) Socrates continues describing the education of the Guardians. They must not be told death is an evil, or they will not protect the state with their lives. They must hold truth as a virtue, and (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) punish lies (except those that save the state) and be kept away from all shameful deeds. This goes so far as to ban even the mimesis of evil deeds or evil rulers in tragedy or epic. Their education must be a balance of music and athletics, to keep them of the right balance of character. Socrates then introduces the fable that there are men of gold, silver, and bronze. Yet it is not assured by birth, bronze parents may raise a gold child, for instance. The guardians themselves, people found to be of the best quality, must be kept from the possession of money or property. The guardians must be dedicated to the state’s good, rather than their own; for this is the only way they will keep their minds on their task. So both wealth and poverty must be avoided. Finally, they are to establish the festivals of the gods. Socrates then goes on to describe further the education of the guardians: key qualities are lawfulness and moderation in their appetites. Justice, then, consists in each person in the city doing their own task without bothering the others. He then discusses the desires – that they are a beast-like part of the spirit that desires only fulfillment. This desire is regulated by two other parts of the spirit: reason and thumos (high spirit). The various parts of the soul – like the men in the city - have to be brought into harmony, as music. Glaucon, Adimantus, and Thrasymachus challenge Socrates on his statement that the guardians must share their wives and children in common. He argues that women are equally capable of being guardians, though less likely. The best men and women are to be encouraged to breed, and this will be one reward for good service to the community. He compares this to the breeding of hunting dogs or horses. The children of the guardians are to be trained in war from a young age, and brought to battles to be ‘blooded’ like hunting dogs. They are not to take fellow Greeks as slaves, but only barbarians. Socrates makes a distinction between the lovers of truth and lovers of opinions. Socrates tells the parable of the ship; wherein a shipmaster is overthrown by an assembly of the sailors, which appoints the most persuasive to posts of authority and throws out the educated pilot as a ‘babbler’ and ‘stargazer.’ Thus the disdain for philosophy in Athens. The teachings of the sophists teach people to be persuasive, not to know what they are doing. Indeed, the Guardians must be true philosophers concerned with being and not seeming. He asserts that the soul contemplating truth is like the eye that sees in daylight, while when it only ‘opines’ it is like an eye trying to see in the dark. The Famous Allegory of the Cave. Note that the duty of philosophers is to return to teach the inhabitants of the cave. Education must consist of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and dialectic; as all these bring one to further contemplation of true things. They are only to be taught dialectic as adults, so that they will not play with it foolishly. Then they must hold commands in war and political office to the age of 50, when they shall turn back to philosophy. Socrates discusses the types of constitutions. Regal (his own), timocratic, oligarchic, democratic, and tyrannic, comparing them to a type of person and their devolution from the preceding form. Not even his own constitution will last forever. The timocratic most desire honors, the oligarchic wealth, the democratic freedom, the tyrannical safety. Each is an attempt to correct the imbalance of the previous form. This is a discussion of the tyrannical man himself. His desires are unordered, impious, and especially subject to the animalistic part of his soul. He is even willing to rob or murder his own father to maintain his rule. Pleasure and pain are contrasted, but there is a middle way between them. The bodily pleasures are seen as simply the absence of pain; while true pleasure comes from knowledge and truth. Socrates then makes an absurd argument, which even Glaucon laughs at, that the tyrant is 729 times as unhappy as the regal man. The truly good man will keep his eye on the ‘real’ (ideal) city in his mind, but will want to keep order in his own soul, participating only in those aspects of public life that improve his soul. 38) Aristotle – Philosophy – 384-322 BC a) Life: b) Works: i) Poetics* ii) Politics I (more, but not on list) iii) Nicomachean Ethics I-II 39) Demosthenes – Oratory, Politician – 384-322 BC a) Life: b) Works: i) Against Conon* ii) Against Pantaenetus* iii) Against Boeotus* iv) Against Dionysodorus* 40) Theophrastus – Philosophy – 371-287 BC a) Life: b) Works: i) Characters 41) Menander – Comedy – 342-291 BC a) Life: He was born to a wealthy Athenian family and presented his first play, the Orge, when he was 21 years old. He won first prize in 316 with his production of the Dyskolos at the Athenian Lenaea and is said to have written a very large number of plays in the New Comic style. Unfortunately, though appreciated in antiquity, only 1 play has survived nearly intact (The Dyskolos, which was discovered in papyrus form in 1958). New comedy, not nearly so free of speech as the Old, takes on a non-political, comedy of manners style, largely dependent on the more melodramatic plays of Euripides (Iphigenia among the Taurians, Ion) b) Dyskolos* i) Knemon is the Dyskolos (“Grouch”), a man who refuses to interact with other human beings and attempts to live entirely on his own. He thus constantly abuses visitors and guests to his farm. When Sostratos, a rich young man from the city, falls in love with Knemon’s daughter, his slaves are beaten and insulted. Even Knemon’s step-son, Gorgias, urges the young man to give up his pursuit. Sostratos proves himself to be a hard worker first to Gorgias and, after Knemon nearly dies from falling into a well, to Knemon as well by helping pull him out of the well. In the end, Sostratos’ parents, who happen to be nearby to make a sacrifice, agree to marry him to Knemon’s daughter and to marry their daughter to the young Gorgias. Knemon, badly injured in the fall, is abused by their slaves and forced to attend the sacrifice and dance along with the rest of the community, his new family. 42) Callimachus – Lyric, Criticsm – 310?-240 BC a) Life: b) Works: i) Aetia 1.1, 2, 4.110* ii) Hymns 2, 5 (more, but not on list) 43) Theocritus – Bucolic – 3rd Century BC a) Life: b) Works i) Idylls (1) 1* (2) 2* (3) 6 (4) 7 (5) 11 44) Apollonius Rhodius – Epic and Librarian – 290?–246 BC a) Life: b) Works i) Argonautica (1) I (2) II (3) III* (4) IV 45) Plutarch – Philosophy, History – 46-120 AD a) Life: b) Works i) Parallel Lives (1) Alcibiades (2) Pericles (3) Themistocles (4) Many others, not on list 46) Longus of Lesbos – Novelist – 100-150 AD? a) Life b) Daphnis and Chloe i) 1 ii) 2 iii) 3 iv) 4