FULL TEXT - University of Wisconsin–Madison

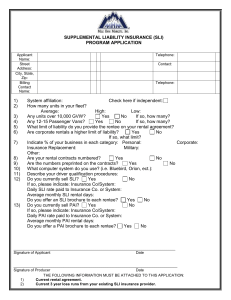

advertisement

Differential Effects of Slowing on Orthographic, Phonological and Semantic Processing in Children with Specific Language Impairment Aimee L. Arnoldussen1; Julia L. Evans2; Mark S. Seidenberg1,3 Neuroscience Training Program1; Department of Communicative Disorders2; Department of Psychology3 University of Wisconsin-Madison Introduction 11 SLI children ages 9;8-13;4 were compared to two nonimpaired groups: 11 chronological age-matched (CA ages 9;11 - 13;1) and 11 younger children (7;0 - 8;9) with similar reading abilities as the SLI group (reading-matched, RM). All children tested within the normal range on IQ. Those with SLI were identified as having expressive and/or receptive language abilities more than 1.5 standard deviations from normal. Reading matches were based on performance on the Woodcock Word Reading Mastery Test (1998). C A -M atch SLI R ead-M atch 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 -Woodcock Reading Mastery Test (WRMT) CLPT 3T whole brain images were acquired from 26 axial slices taken every 3 seconds. After motion correction, a boxcar reference function comparing blocks in each task versus control was convolved with a blood flow response model. Images were transformed into Talairach space and smoothed with a 4mm blur before computing group statistics. Orthography NowordRep SLI children performed worse on reading measures than CA children, but similarly to younger RM children. 100 C A -M atch S LI R e a d- M a t c h 90 80 70 Age-Matched 60 50 SLI Reading-Matched Voxel-wise p<.005, map-wise p<.05. All three groups show similar activation profiles along the left visual cortex and fusiform gyrus. 40 30 20 Phonology 10 0 Exceptio ns No nwo rds PAT fMRI Task Performance The SLI children were slower than the CA group but faster than the RM group. Functional MRI: Tasks: Accuracy 100 Percent Correct SLI children were less accurate than CA children across all tasks. They were similar to RM accuracy for all tasks except phonology, where the SLI group performed poorest. Age-Matched SLI ReadingMatchedp<.005, map-wise p<.05. Looking at the 2 non-SLI groups, there Voxel-wise is a developmental trend with younger RM showing more activation than older CA children. The SLI children depart from this pattern with additional activation in left MFG, IFG, precentral gyrus, fusiform gyus and visual cortex. Semantics CA-Match SLI Read-Match 95 90 85 80 75 70 65 Orth Phon Sem Speed: Summary Conclusions about speed deficits in SLI depend on which group the SLI children are compared to. They are slower than same aged non-SLI children (CA) but faster than younger non-SLI children with similar reading/language abilities (RM). Accuracy: Conclusions also depend on comparisons. SLI children were less accurate than CA children across all tasks, but performed as well as the younger RM children on the orthography, semantics, and matching tasks. They showed a particular deficit on the phonological task, performing more poorly than even the RM group. fMRI Activity: Reading -Competing Language Processing Task (CLPT) -Nonword Repetition (Nonword Rep) -Exception Word Reading (Exceptions) -Nonword Reading (Nonwords) -Phonological Awareness Test (PAT) Children were instructed to choose the word that spelled, rhymed or was in the same category as the picture as quickly and accurately as possible. A nonlinguistic shape matching control task was also included. All children received practice in order to confirm task understanding. Performance was assessed by reaction time and accuracy. fMRI Results 0 Methods Behavioral Measures: The SLI group performed significantly worse than CA children, but similarly to younger RM children. 1 00 Percent Correct Participants Verbal Working Memory Pe rce nt Corre ct Several competing hypotheses have been proposed concerning the bases of Specific Language Impairment (SLI). One is that SLI is secondary to general slowing in the processing of information (Kail 1994; Miller, Kail, Leonard & Tomblin 2001). Our study investigated the speed of orthographic, phonological and semantic processing in children with and without language impairments and brain activity measured by fMRI. Behavioral Measures Match Age-Matched SLI Reading-Matched Voxel-wise p<.005, map-wise p<.05. Similar developmental trend. Among non-SLI, increase in skill is associated with less activation. The SLI group produced additional activation compared to both normal groups, in the left frontal and visual/fusiform areas to a greater degree than either normal group. In the two non-SLI groups, there is a developmental trend: younger, less skilled RM children produce more activation than older, more skilled CA children. The SLI group does not fall on this developmental continuum. Rather, they exhibited the largest amount of activity, even more than the RM group to whom they were matched on reading/language ability. These findings are consistent with other research showing greater brain activity for more difficult tasks and for clinical populations with relevant behavioral impairments. Conclusions: We have reported preliminary findings from a study for which additional analyses are being conducted. To this point the results underscore the importance of: 1. Comparing SLI children to both same-aged and younger reading/language matched children 2. Assessing performance on multiple components of language 3. Examining behavioral (speed, accuracy) and fMRI data together The SLI children were consistently slower and less accurate than sameaged non-SLI children, consistent with a generalized slowing hypothesis. However, comparisons to the RM children and performance on the different tasks yield a more complex picture. If the language impairment in SLI merely reflected generalized slowing we would have expected the SLI children's performance to pattern more closely with the younger RM group. Moreover, the imaging data suggest that the SLI children do not fit on the normal developmental trajectory defined by RM and CA groups. The SLI children were comparable to the other groups on the orthography task but not phonology or semantics, producing greater activity than even the younger subjects. Although the data from this study continue to be analyzed, the results to this point suggest that slowing is a consequence of another type of underlying impairment (e.g., one related to phonological processing) rather than the proximal cause of language delay. Special thanks to Lisbeth Simon for help in subject recruiting and clinical assessments. We also wish to thank Jeff Binder consultation on the imaging component. This research was supported by NIDCD R01DC005650 (Evans) and NICHD RO1MH29891 (Seidenberg).