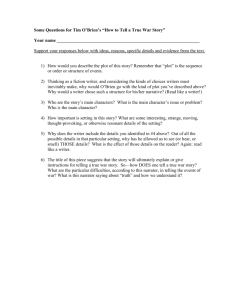

323 Fiction Critique Form

advertisement

323 Fiction Critique Form Critiquer ________________________ Story writer ______________________ To the critiquer: you should write a minimum of one well-developed paragraph for each numbered item below. (If you come up short, you should provide more specific detail to illustrate and support whatever you are claiming. You should also review any course materials on fiction as well as the Fiction Check List for specific elements you can address and ideas you can consider. These critiques are for the writers, yes; but they are also for the critiquers—to help you gain critical awareness and practice reading with care.) It helps to use a font style or color to distinguish responses from questions. Print out your finished critique, STAPLE all pages, and bring to class. 1. What, right off the bat, do you especially like about the draft you’ve just read? What seems especially imaginative, or smart, or vivid, or well-written? Is it just flat-out fun to read? Is it weird and intriguing? Provide details, quotes. 2. What is the story’s PLOT? That is, what happens first, then second, then third…etc.? Write a summary of the plot here, explaining, if necessary, any trouble you might have had identifying the plot: 3. What is the story’s narrative question? What explicit or implicit question is posed at the beginning, and the reason we keep reading? Is the question adequately interesting? 4. Does the plot in turn rely entirely on an "O'Henry twist" or trick ending? This is fun maybe once or twice, but it gets old really fast and it starts to feel cheesy and canned. You should only be doing this sparingly. The outcome is a foregone conclusion for the writer and so no discoveries have been made and the writing experience itself is drastically diminished. One of the central pleasures in writing—for the writer—has been missed. Comment on this aspect of the draft: 5. How well-paced and modulated is the plot? Is it "front-heavy"? That is, does it have page after page of initial scene-setting and exposition, followed by screaming slide to a conclusion? Does it alternate action scenes with dialogue and/or reflective or descriptive segments, or is it just one action event after another? Is there excessive dialogue which would benefit from alternation with action, description, etc.? Where, if at all, does the story SLOG? Where does it go TOO FAST? Where might the narrator slow down, provide detail, drama, scene development—and where should the pace pick up (what might the writer just skip over as in “jump cuts”)? 6. How satisfied are you with the ending? Two common problems to help your classmate with: a. Suicide and murder endings. These are mostly a cop-out; you can’t get your character out of his/her problems, so you have them whacked! (lol). Gotta do better. If you can’t figure out how to end the story, we can discuss it with you or can leave it indeterminate. b. Neat and pretty bow endings. Most of our experiences do not end in tidy resolutions. Given the length of most short stories, especially, heavy closure often feels wrong and contrived. Sometimes it’s better just to stop, shut up. Let the reader sense where the narrative ultimately goes. Comments: 7. Who is the main CHARACTER? How well-developed, round, complex, and distinctive is the character? A problem with characters in the stories of beginning writers is that they are often indistinguishable from anyone else in the story. That is, they are generic and leave no impression on us. (Beginning writers often focus on clever, exciting plots at the expense of characterization.) Do you really know or strongly sense the central people in the story—their desires, physical quirks, beliefs, contradictions? Comment on this story’s development of character: What suggestions can you make for better characterization? 8. Another element often neglected is SETTING—both the general setting (place and time) as well as specific settings (particular rooms, spaces). A story’s setting can reveal all kinds of nuances about a character, provide suspense and atmosphere, and in general bring a story to life. Comment on the use of setting in this draft: 2 9. Does the language of the piece SHOW rather than TELL? Is there real engagement with LANGUAGE in the draft? Does the piece include some evocative, surprising, moving, vivid, juicy metaphors and similes? Is there ample, vivid, concrete, sensory details? Or, oops, is the prose style pretty much a soggy paper towel? For instance, does the story tend to use hackneyed, cliché words and expressions such as the following: a. b. c. d. e. "sly smile" “icy blue eyes” "evil smirk" "peering deep into his eyes" "bitter tears" or overcooked dialogue tags (these should be kept to a minimum): f. …,” Mary sighed. …,” John retorted. …, Heather raged. …,” Jack whined. See if you can make rage, whining etc. come through the dialogue itself—word choice, syntax—or action or nuanced facial expression. Comment on the draft’s prose style: 10. What is the answer to the narrative question? Is it adequately surprising and insightful? Overall, how satisfying is the story at this point? 11. What sort of fiction and art is the piece trying to be? Recall our perspectives wheel the first week of the semester and some or all of these questions: where would you position this piece? Is it primarily showing life as it really is (mirror), life as the writer wishes it were (escapist), an alternative understanding of life (challenging, strange), etc.? What does the story seem to ask or require of the reader? Is the story written as a formula or as innovation? Is it primarily authorcentered or audience-centered? 12. Any final thoughts? What questions could you ask the writer? 3 4 5