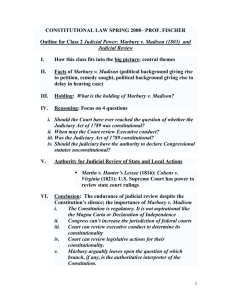

Judicial Review Reading

advertisement

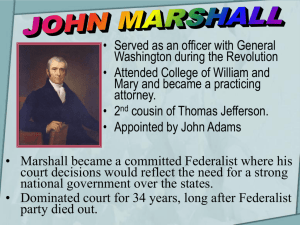

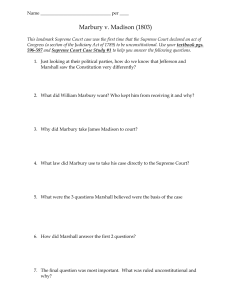

The Principals of Judicial Review Who was the most influential American of the founding era of the United States: George Washington, due to his military and political achievements? Thomas Jefferson, for the Declaration of Independence and the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase? James Madison, for his "writing" of the Constitution and subsequent service in the House of Representatives, as Secretary of State, and President? Or might it be John Marshall, who served as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court for 34 years, longer than any other Chief Justice, and whose ground-breaking decisions still affect the lives of every American? It is safe to say that as Madison was the "father" of the Constitution and Washington the "father of the powers of the Presidency," Marshall was the "father of the Supreme Court," almost single-handedly clarifying its powers. What if the Supreme Court did not have the power to review laws or executive decisions, to overturn those that are "unconstitutional" - how different life might be in the United States? Until 1803, it was not a foregone conclusion that the Supreme Court of the United States would have that power, despite the fact that judicial review had its origins in early seventeen-century England and had been asserted by James Otis in the period leading up to the American Revolution. A relatively minor lawsuit led to one of the most important Supreme Court decisions in American history, Marbury v. Madison, laying the foundation for the Court's ability to render its decisions about laws and actions. In Marbury v. Madison, the Supreme Court claimed the power to review acts of Congress and the president and deem them unconstitutional, creating a precedent for an American process of judicial review. Through the decision of Chief Justice John Marshall, then, the court assumed the powers with which it has since played such a vital role in American life. The Origins of Judicial Review The Constitution does not specifically mention judicial review. Where does this practice come from? Colonial Roots. Before the revolution in 1775 the English Privy Council (advisers to the king) in London regularly reviewed acts of the colonies to make sure they complied with English laws. During the Revolution each of the colonies formed state governments. Between 1778 and the Constitutional Convention in 1781, the courts in several states adopted the practice of overturning laws which they found violated their respective constitutions. Thus, legal precedent had established judicial review as a well-known practice before the Constitution was written. When the founders wrote the Constitution, few doubted that they intended the federal courts to have authority to declare state laws unconstitutional. However, the Constitution did not indicate clearly that they intended the Supreme Court to have the same power to review acts of congress or of the President. A constitutional Debate Starts. During the debate over ratification of the constitution, Alexander Hamilton argued that the Constitution implicitly gave the Supreme Court the power of judicial review, even it it did not state that delegation of authority explicitly. In The Federalist (#78) Hamilton wrote: The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between the two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the Constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents. John Marshall, a young lawyer from Virginia, who supported the Constitution, summarized the need for judicial review. To what quarter will you look for protection from an infringement on the Constitution if you will not give the power to the judiciary (the Supreme Court): There is no other body that can afford (offer) such protection. Other political leaders of the time did not share Marshall’s enthusiasm. As the new government began to operate, Thomas Jefferson emerged as a leader of those who opposed extending the Court’s use of judicial review to include supervision of the executive and legislative branches of the national government. Jefferson wanted each of the three branches of government to interpret the meaning of the Constitution. Thus Congress would decide for itself whether or not its actions violated the Constitution. Likewise, the president would review the constitutionality of executive actions. Jefferson presented an alternative to the system of judicial review: My construction of the Constitution is…that each department is truly independent of the others, and has an equal right to decide for itself what is the meaning of the Constitution in the cases submitted to its action most especially where it is to act ultimately without appeal…Each of the three departments has equally the right to decide for itself what is the duty under the Constitution, without any regard to what the others may have decided for themselves under a similar question. When Jefferson won the presidential election in 1800 the question or whether or not the Supreme Court would exercise judicial review over acts of Congress or of the President remained unresolved. The Court first asserted the power of judicial review of congressional actions in a case stemming from the bitterly contested election which brought Jefferson to office. *Remember how Jefferson won the election and who ran against him for the office.* Marbury v. Madison (1803). William Marbury was one of the forty-two men awaiting “midnight appointment” signed commissions from President Adam’s administration on March 3, 1801 appointing them justices of the peace for the District of Columbia. The President, a Federalist, rushed the appointments of these loyal Federalists through the Senate just before his term of office ended. He hoped to leave his successor, the Democratic-Republican Jefferson who took office March 4, 1801, with a court system packed with opponents. Adam’s plan faltered when his Secretary of State, John Marshall, failed to deliver all the commissions before Jefferson’s inauguration. Discovering Adams’ plan, President Jefferson instructed his new Secretary of State, James Madison, not to deliver the remaining commissions, one of which was Marbury’s. In an effort to force Madison to release his commission, William Marbury examined the Judiciary Act of 1789. The act allowed Congress to establish a system of federal trial courts with broad jurisdiction which in turn created an arm for enforcement of national laws within each state. He found that the act had given the Supreme Court the power to issue writ of mandamus, orders forcing public officials to perform their official duties. Armed with this law, Marbury petitioned the Supreme Court, asking the justices to issue a writ to Madison commanding him to deliver the commission. When Madison refused to obey the writ of mandamus the case came before the Supreme Court. The Court held that Marbury had a right to the commission he demanded, according to the Judiciary Act of 1789. However, the Court also decided that it had not right under the Constitution, to issue a writ of mandamus forcing Madison to deliver the commission to Marbury. Chief Justice John Marshall explained the decision, establishing a precedent for judicial review of congressional acts. Marshall examined Article III, Section 2 of the constitution to determine what sorts of cases the Supreme Court had original jurisdiction over – cases for which court action would begin at the Supreme Court level. The Supreme Court is primarily an appellate court, empowered to hear appeals from lower courts and has few original jurisdiction powers. Article III did not include issuing writs of mandamus within the court’s original jurisdiction. Thus, part of the Judiciary Act violated the Constitution. Applying the principle of judicial review, Marshall wrote: Certainly all those who have framed written constitutions contemplate them as forming the fundamental and paramount law of the nation, and consequently the theory of every such government must be that an act of the legislature, repugnant to the Constitution is void. The Supreme Court declared one part of the Judiciary Act of 1789 unconstitutional. Thus William Marbury failed in his bid to acquire the commission appointing him a justice of the peace. Far more significantly, the Supreme Court had asserted the power of judicial review, establishing a precedent for the development of a main principle of constitutional law in the United States. In later decisions, federal judge’s ruling other legislative actions unconstitutional based on their right to do so on John Marbury’s arguments in Marbury v Madison. Thus, Marshall established a precedent that has become an integral part of constitutional government in the United States. "It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is." - Chief Justice John Marshall, in Marbury v. Madison, 1803-