Slides from my talk - Barbara Gail Montero

advertisement

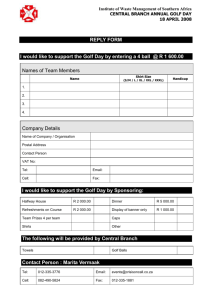

Does thinking interfere with doing? Yale Symposium on Skills and Practices April 2014 Barbara Gail Montero The City University of New York bmontero@gc.cuny.edu Sometimes, when it really matters, everything falls apart. During the 2011 Republican primary presidential debate, in listing the three governmental departments he was planning to eliminate, Rick Perry couldn’t call to mind the phrase “the department of energy”: The third agency of government I would do away with…the education, the uh, the commerce and let’s see, I can’t—the third one. I can’t. Sorry. Oops. He curtailed his campaign shortly after this. Though other explanations are possible, it seems that Perry’s career-ending choke was in part due to his heightened state of anxiety over how well he was going to be perceived. But how does anxiety cause a choke? Explicit-monitoring theory: Pressure can cause one to explicitly attend to or consciously control processes that would normally occur outside of consciousness. (Baumeister 1984, Masters 1992, Wulf & Prinz 2001, Beilock & Carr, 2001, 2005, 2007, Wallace et al 2006, Beilock & DeCaro, 2007, Ford et al 2009, Beilock 2011 and Papineau forthcoming.) On this view, choking can occur in public speaking when individuals try to bring into working memory information they should be able to say automatically. In the psychology literature, explicit-monitoring theory is the prevalent explanation of choking under pressure in sports. Sian Beilock explains, Highly practiced skills become automatic, so performance may actually be damaged by introspection, which is characteristic of an earlier, consciously-mediated stage. [Athletic skills] are hurt, not because of worrying, but because of the attention and control that worry produces (Beilock et al. 2004). Her advice: “Distract yourself…don’t give yourself too much time to think, focus on the outcome, not the mechanics… [and] just do it.” Indeed, “just do it,” she says, seems to be “the key to high-level sports performance.” But does thinking interfere with doing? That is, does thinking about (or monitoring, or conscious control over) your actions cause poor performance at the expert level? Thirteen-time PGA winner Dave Hill claimed, “Golf is like sex. You can’t be thinking about the mechanics of the act while you are performing.” But why not? The “just-do-it principle” (thinking interferes with expert performance) is purportedly supported by: I. Varied-focus experiments II. Verbal-overshadowing experiments III. Expertise without knowledge IV. Statistical data Just-do-it is countered by or in tension with: V. Distraction theory VI. Qualitative Studies VII. Anecdotal Accounts VIII. Analysis of Steve Blass’s troubles IX. Heideggerian account of public speaking X. Philosophical analysis of Dave Hill’s analogy I. Varied-Focus Experiment • Novices and experts perform a skill under three conditions: • As they usually do. • While performing a skill-related supplementary task • While performing a skillunrelated supplementary task. Beilock and Carr (2002) experiment: Gabrielle Wulf (2007) summarizes the research in this area by saying that the “findings clearly show that if experienced individuals direct their attention to the details of skill execution, the result is almost certainly a decrement in performance” (p. 23). So should expert athletes, as Beilock claims, just do it? Let me present three reasons to question the justdo-it conclusion of these experiments. Objection 1: The experiments are “ecologically invalid.” • In the wild, athletes do not report on past actions. • In the wild, athletes are highly motivated, so skill-unrelated distractions harm. • CUNY undergraduate Lorenzo Ruffo’s point: Adderall usage. Sutton’s (forthcoming) analogy to driving while continuously monitoring the rearview mirror illustrates the odd nature of the task. Increase the difficulty of the skill-unrelated supplementary task or decrease the difficulty of the skillrelated supplementary task and the results may not be the same. (I did this in a chess experiment.) Sutton thinks that because the varied-focus experiments fail to capture real-life settings, we need to discount their results. But I have a further question: Both groups perform ecologically invalid tasks, yet ability is differentially affected. Why is this if not for the reason, as Beilock (2002) concludes, “well-learned performance may actually be compromised by attending to skill execution”? Objection 2: The skill-related supplementary task may be more distracting for those who are faster at performing the skill. The more-skilled soccer players have to look back further when the tone is sounded. Consciously focusing on one’s feet might be compatible with optimal performance while reflecting back on past foot action may not be. Objection 3: The “experts” are not experts. • It is nearly impossible to get experts into the lab. • What are experts? • Studying expertise is the really hard problem ______________________________________________ Public Anouncemnt WE WILL PAY YOU $4.00 FOR ONE HOUR OF YOUR TIME II. Verbal Overshadowing Experiments Flegal and Anderson’s (2008) golf experiment compared: • Performance after reviewing prior performance. • Performance after completing a word-puzzle. Flegal and Anderson 2008 Flegal and Anderson conclude (2008): Whereas verbalization assists in the early stages of acquiring a skill, it may impede progress once an intermediate skill level is attained…This, as they see it, suggests “a new view of an old adage: Those who teach, cannot do.” But is this the correct conclusion to draw? The participants in the study were told to “record every detail” they could remember “regardless of how insignificant it may strike” them. One idea: Perhaps focusing on the irrelevant aspects of performance is detrimental. However, the lesser skilled players were also asked to do this, yet their performance improved. Another idea: Flegal and Anderson’s “more highly skilled” participants were college students of whom only 65% had ever taken a golf lesson. Relevance: • Such players may have found their skill plateau wherein action is both more proceduralized than a beginner’s and less conceptualized than an expert’s. • Many of the more highly skilled participants were never trained to conceptualize their actions. The detrimental effect of conceptualization on perceptual judgments is thought to play a role in Wilson and Schooler’s (1991) jam-tasting experiment. • The researchers’ conclusion: “Analyzing reasons can focus people's attention on nonoptimal criteria.” • Malcolm Gladwell (2007) puts it more colorfully: “By making people think about jam, Wilson and Schooler turned them into jam idiots.” Yet the expert jam tasters employed by Consumer Reports and who served as a standard for accuracy were, presumably, not negatively affected by verbalizing their preferences. It may very well be that expert golf players would not be hampered by recording what they had focused on during the putting task. Schooler's more recent work suggests that with training people are able to conceptualize their perceptual judgments without this interfering with their performance. Melcher & Schooler’s (1996) wine tasting experiment. Melcher & Schooler’s (2004) mycology experiment. III. Those who do, can’t teach Philosophers have focused on examples of experts who appear to have no understanding of how they perform their skills. Let us examine six examples of diverse “magical” skills as they are presented by various philosophers. 1. Kant comments that Homer cannot teach his method of composition because he does not himself know how he does it (Critique of Judgment sec 47). 2. Robert Brandom (1994) and John McDowell (2010) cite the chicken sexer who can’t teach anyone how he makes his judgments because he does not know himself. 3. Stephen Schiffer (2002, p. 201) supports one of his arguments against Jason Stanley’s view that know-how is inextricably connected to propositional knowledge by citing eight-year-old Mozart’s apparent ability to compose a symphony without being able to explain how to do so. 4. David Velleman (2008), in arguing that we achieve excellence only after we have moved beyond reflective agency, cites the Zhuangzi in which the skill of wheelwrighting is described as proceeding without any understanding of how it is done: You can’t put it into words, and yet there’s a knack to it somehow. I can’t teach it to my son, and he can’t learn it from me. 5. In Plato’s dialog Ion, Socrates says that the poet and the rhapsode’s actions are a form of madness since they have no knowledge whereof they speak. 6. In pointing out how scientific hypotheses may be hit upon suddenly and unsystematically, Carl Hempel (1966) recounts the chemist Kekulé’s story that in 1862 the idea for the ring structure for benzene came to him in a flash after dreaming of a snake biting its tail. What do I make of such views? Kekulé himself in his breakthrough paper claims that his theory was formed in 1858, four years prior to the dream. The proverbial chicken sexer who has no understanding of how he is making his judgments simply doesn’t exist. Nakayama et al (1993) makes this abundantly clear in an article explaining in painstaking detail just one of the intricate methods that chicken sexers learn. Aristotle had a theory of chicken sexing (On the Generation of Animals). Former poultry sexer Tom Savage: Poultry sexing is based upon the acquired ability to recognize/differentiate anatomic structures within the chick's cloaca. There is little evidence that Mozart had no understanding of what he was doing or that he composed without thinking about it. Eight year old children are often capable of detailed explanations of their skills. Moreover, the extent of his compositional genius at that age is also somewhat contested: Handwriting analyses indicates that his father played a significant role in his compositions until Mozart was thirteen and not merely as an amanuensis (Keys 1980). And as an adult Mozart didn’t compose without thinking. In a well-known letter, he claims to see in his mind entire compositions finished “at a glance” and “all at once” and that all the inventing “takes place in a pleasing lively dream.” This letter is now dismissed as a forgery and his actual letters make no comments about sudden insights (Spaethling 2000). His sister has documented that he would spend endless hours mentally composing his music (Stafford 1993). Furthermore, Tyson’s (1987) studies of the autograph scores reveal that some manuscripts contain numerous revisions. We lack similar archival data about Homer’s method’s of composition and the ancient wheelwright’s approach. And Homer famously does say in the opening lines of the Odyssey: “Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story.” Whether the authors of the Zhuangzi are basing their claims on what actual wheelwrights said is unknown. Socrates, however, certainly doesn’t listen to Ion: After arguing that Ion’s abilities cannot be rational, Ion responds: “[although your reasoning appears unassailable] I doubt whether you will ever have eloquence enough to persuade me that I praise Homer only when I am mad and possessed” (Ion, 536, d). This line is sometimes cut when the dialog is anthologized (Bychkov and Sheppard 2010), but it’s important! Socrates not only doesn’t take Ion’s claims seriously, he apparently had never even observed Ion in action. IV. Statistical Analysis of Choking Is there a statistically significant decrease in skill in situations in which athletes are thought to be relatively more skill-focused? • Archival data from baseball World Series between 1924 and 1982 illustrate home teams choke in decisive games (Baumeister et al. 1984). • An expanded data base that include games through 1993, eliminates the statistical significance of the hometeam choke (Schlenker 1995,Tauer et al. 2009). •Also: In football, “icing the kicker” is ineffective (espn.go.com/blog/statsinfo/post/_/id/34217/ icing-the-kicker-remains-ineffective-practice). V. Distraction Theory of Choking The self-focus account of choking says that choking occurs because pressure induces experts to focus on their skills. Distraction theory says basically the opposite: high pressure draws attention away from the task at hand and to irrelevant aspects of performance (Wine 1971). Distraction theory is supported by the idea that anxiety impairs working memory and executive control (Ashcraft & Kirk, 2001; Eysenck et al., 2005; Hayes et al., 2008), both of which are important components of, among other things, planning and strategizing, or, in other words, thinking while doing. Also, high anxiety induces various physiological changes that appear to hinder performance. The fight-or-flight response which anxiety produces shunts blood flow to the larger muscles, leaving cold feet and hands, and thus motor skills relying on the hands or feet may be harmed. It can cause loss of peripheral vision, increased perspiration, and tremors. These points may be obvious, but they are often not mentioned in the literature on choking. The choke is thought to be something different in kind. But is it? VI. Qualitative Studies of Thinking while Doing Qualitative studies oppose the just-do-it principle. Adam Nicholls and colleagues (2006) asked elite athletes to keep a diary of stressors that occurred and coping strategies they employed during games, as well as to rate how effective these coping strategies were. The most common method of dealing with stress involved redoubling both effort and attention and such methods were perceived as more effective than other methods. Collins and colleagues (2001), measured kinematic aspects of elite weightlifters’ performance during training and competition and questioned these athletes about their conscious use of any movement-change strategy in response to competitive pressure. Although the participants modified their movements as a result of competitive pressure, and claimed to do so consciously, such modifications did not diminish their overall performance. In a study by Hill et al. (2010), interviews with elite athletes revealed that distractions (rather than self-focus) were seen as the main cause of choking (p.227). Qualitative studies have limitations, but, as we saw, so do the more controlled studies by Beilock and others. Toner and Moran (2011) conclude from their research, reasonably enough, that it is the type of thought that matters: Experiment 1: Monitor your golf put and report where on the putter face you struck the ball. Experiment 2: Think out-loud while holing balls. Toner and Moran conclude: Golfers may need to choose their swing thoughts very carefully because focusing on certain elements of movement, such as the impact spot, could lead to an impairment in performance proficiency” (680). I wonder if they even need to be careful about this? VII. Individual Cases illustrating thinking in action Tennis player and coach Timothy Gallwey: “When I hit my backhands, I am aware that my shoulder muscle rather than my forearm is pulling my arm through….Similarly, on my forehand I am particularly aware of my triceps when my racket is below the ball.” Cellist Inbal Segev: My teacher, who was a student of Casals would say “don’t let the music lead you; you need to direct it.” Getting lost in the music is a mistake, she said, as it precludes thought. Anecdotes in philosophy? ________________________________________________ Theory Intuition General claims X Anecdotes _________________________________________________ They illustrate a view They add interest They reveal what inspires theory VIII. Steve Blass Disease, Steve Sax Syndrome Dreyfus (2007) supports the idea that attention to and conscious control over one’s highly-skilled actions degrades performance in part by citing the fate of former Yankees second baseman, Chuck Knoblauch, who “couldn't resist stepping back and being mindful” (354). The view is found in the popular press as well: “ [Just like Novotna] faltered at Wimbledon…because she began thinking about her shots again, …[Knoblauch] under the stress of playing in front of forty thousand fans at Yankee Stadium, [found] himself reverting to explicit mode” Gladwell’s (2000). John McDowell (2007): [Knoblauch lost his ability because] he started thinking about ‘the mechanics,’ about how throwing efficiently to first base is done…This kind of loss of skill comes about when the agent’s means-end rationality tries, so to speak, to take over control of the details of her bodily movements, and it cannot do as good a job at that as the skill itself used to do. But what reason is there to think that Knoblauch, or any of the other major league players who have been struck with similar performance failures suffered because they were thinking about what they were doing? The former Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher Steve Blass (2012) mentions numerous theories about what might have been causing his “control problem”: • Faulty mechanics • Personal problems • Too tight underwear Never once does he mention that it might have been due to thinking too much about what he was doing. What he was aware of: Before my control problem I had the ability to just concentrate on the immediate task at hand, which is a wonderful thing for an athlete. I could block out family, world hunger, or anything that was going on, because of that focus. That focus all went away and everything was occurring in my mind. I was like an antenna. It sounds as if the problem is not thinking too much about his actions, but not being able to think enough about them. IX. Do similar considerations apply to public speaking? According to Dreyfus (2013), “in total absorption, sometimes called flow, one is so fully absorbed in one’s activity that one is not even marginally thinking about what one is doing.” He cites Merleau-Ponty: The orator does not think before speaking, nor even while speaking; his speech is his thought. The end of the speech or text will be the lifting of a spell. It is at this stage that thoughts on the speech or text will be able to arise. Heidegger tells us that when a lecturer enters a familiar classroom, the lecturer experiences neither the doorknob nor the seats; such features of the room for the lecturer are “completely unobtrusive and unthought.” All of such things would indeed seem to be beneficially unthought so as to leave plenty of mental space to think about the lecture. Perhaps we should all be like the high diver on the board prior to her plunge: before speaking, review what we have to say so as to make sure that it is there in our conscious mind; once there, thinking about it will not interfere. I have noticed that excellent speakers do this. And, during his presidential debate, perhaps Rick Perry would have benefited from this as well. X. The question you’ve been waiting for… Earlier I quoted golfer Dave Hill: “Golf is like sex. You can’t be thinking about the mechanics of the act while you are performing.” Is golf like sex? Aristotle had something to say about this. Nicomachean Ethics, book 7, chapter 11: οἷον τῇ τῶν ἀφροδισίων· οὐδένα γὰρ ἂν δύνασθαι νοῆσαί τι ἐν αὐτῇ. (1152b17–18) As with the pleasure of sex: no one could have any thoughts when enjoying that. (trans. C. Rowe.) What is my view? THANK YOU