- Senior Sequence

advertisement

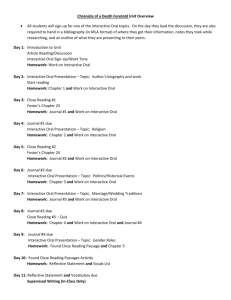

Improving Outcomes for Emancipated Foster Youth An analysis of current programs and strategies A research proposal submitted to the Urban Studies and Planning Program University of California at San Diego Cecilia Aldana USP 186 Section A03 cealdana@ucsd.edu January 30, 2012 Abstract The purpose of this study was to underline the inefficiencies of the aftercare system currently in place that is meant to facilitate the successful transition from wards of the state to self-sufficient adulthood for youth that emancipate or ‘age-out’ of the system or who left care in late adolescence. It aims at demonstrating where there are inefficiencies in the system and where the system backfires on helping emancipated youth reach selfsufficiency. This study also highlights the work of one San Diego based non-profit organization that starts off where the traditional after-care system leaves off. By providing ‘gap services’ and welcoming them in to their “extended family” model of operations, they have thrived at their mission of improving former foster youth outcomes. Key findings included that the traditional system is too fragmented, contradictory, impersonal and convoluted for former foster youth to navigate on their own, leaving them vulnerable to dismal outcomes. Another key finding was that a program like Just In Time’s, which tailors its services to the individual and lets former foster youth join a caring family-type environment, empowers the youth and goes a long way in changing the lives of those serviced Key terms: emancipated former foster youth, foster youth outcomes, self-sufficiency, transitioning youth. Introduction Every year countless teens ‘age-out’ or are emancipated from the foster care system upon reaching the age of eighteen. It is estimated that a large majority of these youth face dismal outcomes in areas such as housing procurement, education 1 Aldana achievement, job attainment, financial fitness, health status and overall well-being. This study looks at current federal, state and local programs aimed at assisting foster youth during their transition from foster care into independent living. It also focuses on legislation relating to foster youth that sometimes impedes their ability to transcend beyond their bleak situations. My research will look at current programs and evaluate their strengths and weaknesses to help determine whether these are sufficient in securing successful outcomes for emancipated foster youth in the aforementioned categories. I will also look into as to why assisting their successful transition into productive adulthood is not only a moral obligation but, from a community’s fiscal health stance, an economically sound one. My research will also ask whether an organization that offers ‘gap services’ to former foster youth can play an important part in helping improve outcomes compared with national statistics. It will focus on innovative strategies currently being used, specifically focusing in on Just In Time for Foster Youth, a non-profit organization based in San Diego, California. This organization sets itself apart from others by offering a unique model of management, what they call the “extended-family” model. The difference in Just In Time’s programs is that they aim at going beyond the traditional services available to foster youth and providing what they call ‘gap services’ or services not traditionally available through federal or state programs. Another distinctive quality of the organization is that their efforts are primarily fueled by an array of volunteers who according to their FY2011 budget compromised approximately $250,000 in man-hours.1 1 ) Just In Time for Foster Youth. “Volunteers.” Retrieved October 17, 2011. http://www.jitfosteryouth.org/index.html 2 Aldana The objective for this research is to contribute to the existing literature regarding programs meant to improve emancipated foster youth outcomes and to present a casestudy of one organization’s attempts at doing so. The goal is that others can learn from and emulate this model. People should care about this issue both from a moral and economic standpoint because as former children of the state, we as members of said state are all responsible for supplying the tools necessary for their well-being. If we do not invest in their futures, this segment of the population is more likely to become frequent and extensive users of our public safety-net services, become incarcerated, become homeless, commit suicide, have unplanned pregnancies and incur unmanageable financial debt, all of which are community problems and should be addressed as community planning issues. Conceptual Framework/Literature Review The issue of emancipated foster youth outcomes is a topic that has been widely discussed in existing literature. It is one of great importance because it deals with the lives and futures of vulnerable youth who have been removed by the state from their family homes for reasons of abuse or neglect in order to protect them. Many of these children end up in group-homes, institutions or bounced from foster home to foster home, where learning the skills necessary to become thriving adults are often insufficient or simply non-existent. A recent report lead by a sub-committee of the Commission of Children Youth and Families found that 72.2% of youth in foster care, have had “between 3 Aldana 6-10 or over 10 school placements” while in the child welfare system.2 This disruption in educational attainment leaves these already vulnerable kids at more of a disadvantage than the average youth. Furthermore, upon reaching the age of eighteen and being deemed adults by the courts and popular culture, they find themselves dumped from the system that has “protected” them with very little life skills to aid them in obtaining even the most basic of needs. On any given year there are close to half a million kids in the foster care system, with an average of 3,000 to 4,000 aging-out every year.3 These youth are a population at high risk of having difficulties managing transition dependent from adolescence to independent adulthood. They experience high rates of educational failure, unemployment, poverty, out-of-wedlock parenting, mental illness, housing instability and victimization. They are less likely than other youth to be able to rely on the support of kin. The public policies and corresponding services intended to help them on their way are limited and fragmented.4 Although there are federal programs and policies to help aid in their transitions to selfsufficiency, they tend to be relatively basic, temporary solutions or not available in all states or jurisdictions. For example, the Transitional Housing Program for Homeless Youth, funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, provides housing 2 LEAP (Leadership Empowers All Possibilities) Council report. Released October 2011. Commission on Children, Youth and Families. www.sandiegoCCYF.org 3 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Foster Care Statistics 2009. Child Welfare Information Gateway, May 2011, page 5. http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/foster.cfm 4 Osgood, D. Wayne. "The Transition to Adulthood for Youth “Aging Out” of the Foster Care System." On your own without a net: the transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2005. page 27. Print. 4 Aldana for only up to 18 months and is not universally available.5 Along with programs not being widely available, many times eligibility for services rendered is highly contingent on participation in other programs. For example, in order to qualify for the THP-Plus housing program, which grants up to 24-months of subsidized housing, the youth must also be concurrently enrolled in the STEP program, which is an educational/vocational program.6 This in and of itself is not a bad bargain, but this is not the only scenario out there. There are also current policies and practices that are impediments in promoting a successful transition into independent living for these youth. An example of this can be found in a report headed by the Children’s Advocacy Institute published last year. The report cites that although thousands of children in the foster care system are eligible to receive benefits through the Old Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance Benefits program (OASDI) and/ or the Supplemental Security Income for Aged, Blind and Disabled program (SSI), many times the foster agencies assigned to protect and provide for these at risk youth, confiscate the money provided by these program to pay themselves for the cost of foster care.7 What this means is that while an eligible child in foster care could potentially be accruing much needed savings, which might serve as a 5 Nixon, Robin and Maria Garin Jones. Child Welfare League of America report. Improving Transitions to Adulthood for Youth Served by the Foster Care System: A Report on the Strengths and Needs of Existing Aftercare Services. 2000. The Annie E. Casey Foundation 6 THP-Plus brochure. “Transitional Housing Program for Emancipated Foster/Probation Youth”. Produced and published by California Department of Social Services. 7 The Fleecing of Foster Children: How We Confiscate Their Assets and Undermine Their Financial Security. Published by the Children’s Advocacy Institute, First Star and University of San Diego Law School. Report, 2011. 5 Aldana stabilizing foundation upon exiting the system, they are instead deprived of it by the same system that is meant to look out for their best interests. To add to this injustice, new scientific studies have discovered evidence that “structurally, the brain is still growing and maturing during adolescence,” which has lead scientists to conclude that brain maturation doesn’t peak until age 25.8 These new studies coincide with an increasingly popular idea that young adults are not equipped to be completely on their own until much later than what current policy predicates they are. This means that the current foster care system is sending out underprepared and illequipped individuals to fend for themselves and navigate through an aftercare system that is entirely convoluted and fragmented. Many of these former foster youth have to do so while simultaneously dealing with emotional and mental problems, with very little support from family or other essential support networks (social capital). One recent report produced by the Youth Transition Founders Group (YTFG) reveals that youth face a harder, and frequently losing, battle into independence if they are not “connected by 25.” The theory behind this idea is that in order to successfully transition from adolescence to adulthood, individuals need a stable support network that will help them develop “knowledge, skills and aspirations; and acquire the relationships and connections that will last a lifetime.” 9 Without these, the study concludes, former foster youth have little hope and will most likely fall into the high percentage of youth whose transition into adulthood end bleakly. 8 Transitions: Building Better Lives for Youth Leaving Foster Care. Childrens Action Alliance. Report, 2005. 9 Connected by 25: A Plan for Investing in Successful Futures for Foster Youth. Prepared by The Youth Transition Funders Group Foster Care Work Group with The Finance Project. Report, 2007. 6 Aldana When looking at national statistics for homeless adults or incarcerated persons, an overwhelming percentage of them were at one time or another former foster care recipients. One report states that in any given year, foster children comprise less than 0.3% of the state’s population, and yet 40% of persons living in homeless shelters are former foster children. A similarly disproportionate percentage of the nation’s prison population is comprised of former foster youth.10 This should be concerning to all community members both for ethical reasons and economic ones too. Providing tertiary services to these youth ends up being more costly all around than investing in their futures through preventative services, like mentoring programs, more exhaustive independent living programs and possibly more permanent housing strategies. One San Diego non-profit group that targets chronically homeless individuals within the city of San Diego, has found that investing in more permanent solutions, such as housing and supportive services has been key in significantly reducing the amount of public money spent on emergency services for this population.11 This return on investment is a benefit that should not be overlooked both from a financial and social standpoint. Similarly, a 2007 study published in the Southern Economic Journal, communicates the importance of enhancing economic incentives to foster care 10 Expanding Transitional Services for Emancipated Foster Youth: An Investment in California’s Tomorrow. Published by Children’s Advocacy Institute. Funded by A California Wellness Foundation. Report, January 2007. 11 Home Again: Ending Chronic Homelessness in San Diego. “Project 25.” Retrieved October 17, 2011. http://homeagainsd.org/our-progress/project-25 7 Aldana placements in order to promote more stability to children in the foster care system.12 The authors note that increasing the amount of money given to foster parents each month, can help decrease turnover in foster placements. Since instability and lack of a safe and secure environment are a major part of unfavorable outcomes after emancipation, investing more money while in the child welfare system might be another idea in improving outcomes and curbing adulthood dependence on social services. My main focus of study will involve the acknowledgement of the ‘gap service’ model as a viable option to improving the outcome of former foster youth. Gap services can be defined, but are not limited to, emergency funds for food, car repairs, interview clothing for successful job attainment, laptop computers for those enrolled in higher education or vocational programs, furniture for youth who have attained housing but do not have money to furnish it, and other items that many times are supplied by parental figures. Also, I will focus on the “extended-family” of mentoring, which allows youth to create meaningful and lasting relationships that are richer and broader than the average mentoring program offers its beneficiaries. Research Design/Methods My research is taking place between November 2011 and February 2012. It will consist of several different methods of study, analysis and gathering of information. The most important element of my research design was the acquisition of an internship position at the previously mentioned non-profit organization, Just in Time for Foster Youth. While working at this organization I was exposed to valuable information 12 Duncan, Brian and Laura Agys (2007). Economic Incentives and Foster Care Placement. Southern Economic Journal. (pgs.114-142) 8 Aldana pertinent to my research. While a lot of my data relating to the current programs and legislation was obtained via internet and library investigations, participatory observation and inquiring with the organizations’ staff members also uncovered useful leads to relevant information. The purpose of presenting current information on programs and legislation relevant to the self-sufficiency of emancipated and former foster youth is to present a complete picture of the present state of affairs. This will aid in illustrating where there are inconsistencies and gaps in the current system that curb its primary purpose of promoting successful transitions into self-sufficient adulthood and also to further place the case-study of Just in Time’s efforts in context. National statistics on former foster youth outcomes will be obtained from documents and reports available online via government websites, other statistics collecting agencies and reports. The purpose of retrieving this information and presenting it in conjunction with the Just in Time (JIT) case-study is to juxtapose national former foster youth outcomes with outcomes of former foster youth serviced by JIT to see how services rendered by JIT might help improve outcomes. Admittedly, there are limitations to these comparisons, as national former foster youth statistics are gathered and tabulated using the general former foster youth population. Outcome information obtained from JIT will include only serviced youth, which is limited to a presorted population that has met certain criteria set forth by JIT administrators. This, however, does not mean that important lessons cannot be learned from an in-depth case-study of Just In Time’s procedural and service models on helping improve outcomes for former foster youth. 9 Aldana My research will also include survey information gathered from former foster youth upon initially requesting services from Just In Time. Further information obtained in follow-up surveys executed by JIT staff members, a small portion of which I helped acquire during my tenure as an intern, will also be reviewed and included where relevant and necessary. This information will assist in supporting my thesis by hopefully presenting an efficient formula for helping improve outcomes for former foster youth. I will also limit my criterion to those observed and measured by Just In Time. The last component of my research deals with the economic incentives to helping this population for the city and respective community. Information for this component will be gathered via internet resources and directly from JIT financial reports provided by staff. Financial accounts will not be broken down to precise amounts, but rather will be presented as averages costs, which can nevertheless communicate the cost-benefits I hope to portray. Several limitations in my research deserve attention. When compiling statistics on outcomes for former foster youth, a lot of data was frequently several years old. Also, Just in Times enhanced outcomes for serviced youth could be attributed to their limiting those deemed serviceable to those that qualify using their own scale of self-sufficiency. Findings and Analysis National Statistics Looking at national studies on statistics related to outcomes in the categories of housing, education, employment, financial health, incarceration and long-term social connections, former foster youth face an uncertain and precarious future once they leave in-home care. For example, in the area of housing one study found that 32 percent of 10 Aldana former foster youth had lived in 6 or more places within the first 4 years of first leaving foster care.13 This population’s homeless rate is also concerning. One study reported that 25 percent of those sampled had been without a place to live for at least one night since their departure from the child welfare system.14 Needless to say, this population faces issues of housing instability that current after care programs and resources are not alleviating effectively. When it comes to education, studies show that this population is less likely to earn a high school diploma or GED, much less go on to earn a college degree. One such study, conducted in 2001, found that 37 percent of their sample population of former foster youth had not completed high school or obtained a GED within 18 months of leaving care. An earlier report found that 66 percent of eighteen-year-olds exiting care between 1987 and 1988, had not completed high school. Expectedly this leads to low rates of college attendance amongst former foster youth. Those who do attend are more likely than the average student to drop out due to financial hardships or lack of other vital support. It is estimated that only 1 to 3 percent of former foster youth graduate college.15 When looking at rates of employment and economic self-sufficiency (or financial health), one also encounters astonishingly poor outcomes as well. Former foster youth have higher unemployment rates and tend to earn lower wages than the general Osgood, D. Wayne. On your own without a net: the transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. Print. 14 Osgood, D. Wayne. On your own without a net: the transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. Print. 13 15 Just In Time for Foster Youth. Retrieved February 7, 2011. http://www.jitfosteryouth.org/index.html 11 Aldana population.16 Several studies report that former foster youth have a higher dependency on public assistance than do members of the general population. One national study, found that 30 percent of young adults who were previously foster youth, were receiving some form of public assistance. Another study, found that 32 percent of participants had received some sort of public assistance after leaving care. Most common type of public assistance among females in this study was Aid to Families with Dependent Children, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families or food stamps. Males receiving public assistance most often collected Supplementary Security Income (SSI).17 Another area that is of concern for this population is their involvement within the criminal justice system. It is estimated that approximately 70 percent of state penitentiary inmates were former foster youth.18 Also several studies found that arrest and incarceration rates were higher than the average population upon exiting the foster care system. Of the youth in the 2001 Courtney et al. study, 18 percent reported having been arrested within eighteen months of leaving foster care. The same percentage reported being incarcerated, with 27 percent of them being male and 10 percent female.19 Finally, former foster youth also tend to experience lower degrees of social capital because of their largely unstable living situations while in foster care and after. Social capital, as defined by famed ethnographer Mario Luis Small, is the number of friends and 16 Osgood, D. Wayne. On your own without a net: the transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. Print. 17 Osgood, D. Wayne. On your own without a net: the transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. Print. 18 Just In Time for Foster Youth. Retrieved February 7, 2011. http://www.jitfosteryouth.org/index.html 19 Osgood, D. Wayne. On your own without a net: the transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. Print. 12 Aldana acquaintances an individual has, including the trust they have towards others in their communities, and the number of times they devote to local volunteer activities.20 One report found that only 68 percent of the studied population had maintained a positive relationship with a caring adult other than a parent since the age of fourteen. Of this percentage, only roughly about half of the group reported keeping weekly or more contact with their mentor.21 These statistics compared to those of similar groups in the general population remain low and troublesome. While these shortfall issues may derive from other factors, such as youth stemming from a lower socio-economic background, the majority of emancipated youth leave the child welfare system ill-prepared to tackle the challenges that await them outside. This, coupled with being on their own at such a precarious age without a proper support system to turn to in their moments of need, is why their outcomes continue to rank depressingly lower than those of their non-foster youth counterparts. Legislation, State and Local Programs In November of 1999, the House of Representatives unanimously passed the Foster Care Independence Act of 1999 or HR 3443. This bill included provisions to aid former foster youth during their transitions from wards of the state to self-sufficient adulthood, while also providing funds for programs for children still in care that will help ease their transitions into independence. These provisions include aid for obtaining high school diplomas, post secondary education or vocational training, career advising, securing housing, job acquisition and preservation, assistance with 20 21 Small, Mario Luis. Villa Victoria. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2004. Print. Midwest Evaluation report, 2001. Courtney, et al. 13 Aldana financial matters, nutrition and health related matters and family planning, amongst others. The 1999 act also allowed for states to increase the age of eligibility for Medicaid to up to 21 years, while also extending coverage to all former foster youth that meet certain specified income requirements, not just low-income unmarried women with young children, as was the case before.22 Today, more commonly known as the John Chafee Act, this piece of legislation supplies individual states with flexible funds to design independent living programs (ILP’s) to assist former foster youth ages 18 thru 21 in their aim at self-sufficient independence. One of the most popular programs is the THP-Plus, which provides temporary (up to 24 months) housing to former foster youth in conjunction with a supportive service plan. The Chafee Act also reserves funds for educational grants or Educational and Training Vouchers (ETV) as they are called, which are administered by each state.23 Locally, entities such as South Bay Community Services, the County of San Diego Health and Human Services Agency, and other agencies like the YMCA, are contracted by the state to dispense transitional services to former foster youth and other transitioning youth (agency services are not exclusive to former foster youth). South Bay Community Services located in the city of Chula Vista, for example, offers independent living programs ranging from affordable transitional housing (Trolley Trestle), job skills and educational achievement (Excel), to educational support and financial literacy.24 22 http://www.ssa.gov/legislation/legis_bulletin_112499.html http://www.casey.org/Resources/Publications/ChafeeETV.htm 24 http://southbaycommunityservices.org/services/youth-family-development/ 23 14 Aldana San Diego Youth Services is another agency that provides independent living skills programs to former foster youth in the North and Eastern part of San Diego County. Their services are similar to those offered through South Bay Community Services, with temporary transitional housing provided to youth, along with other services aimed at improving their chances at successful independence from the system. These efforts often include case management and are often subject to eligibility, housing availability and require program participation to receive housing and related services. Other efforts available locally through the San Diego independent living skills (ILS) office include rental assistance through the HOME Emancipated Youth Housing Program. This program offers low-income youth a chance to find a housing situation on their own, which may include a room with a former foster parent, a shared apartment or a single affordable unit. Former foster youth who qualify would only have to pay 30 percent of their monthly income and are eligible for this benefit for up to 24 months.25 Job acquisition would solely rely on the youth, including the furnishing and expenditures related to setting up their living situation. While various mentoring programs do exist throughout San Diego county, like those offered through San Diego Youth Services or thru South Bay Community Services, few go beyond offering the basics and most are reliant on a youth participating in a program of some sort. While the mentoring programs are a good way for the youth to develop connections with caring adults, they can hardly measure up to the monetary contributions and unconditional support that a family 25 http://www.fosteringchange.org 15 Aldana environment can supply these transitioning youth. Problems with These Efforts The problem with current efforts to help former foster youth during their transition to self-sufficiency is that they tend to be fragmented, difficult to access, contingent on various criteria, too basic or insufficient and almost exclusively exceedingly temporary solutions. For example, while former foster youth may qualify for educational grants to pay for tuition for colleges or universities, there are no provisions made for such essentials as bed linens, apartment furnishings and other housing essentials typically provided by parents to an average college age youth. Other educational tools like books and school supplies, not to mention laptop computers for youth to gain that necessary competitive age in today’s educational environment, are rarely obtainable through current state programs and funding. When former foster youth leave dependent care upon reaching the age of 18, many times they have not learned the basic skills needed to properly take care of themselves. These can include proper nutrition and other healthy personal habits. Many have not graduated from high school and do not have the knowledge to access sometimes extremely complicated application processes required to gain federal financial support for further schooling and vocational training. As mentioned before, many have not profited from a suitable education, possibly because of unstable living situations that may have caused them to change schools various times or because of volatile living environments. Of those youth that do manage to graduate from high school or obtain a GED, few go on to post secondary school, mostly because of financial hardships or trouble accessing or 16 Aldana knowledge of financial programs that could pay for further education. While former foster youth are entitled to various benefits through state and local programs, many times accessing them can be difficult for this population. They may not be informed of their existence or they may not qualify due to programs having certain restrictions or limitations. Availability of certain state programs is also dependent on whether a county has requested funding for such and made it available to their local population. For example, if a county does not wish to participate in the THP-Plus program, which provides transitional housing and other independent living skills programs to youth, it is not lawfully obligated to do so. This can be troublesome for youth because it diminishes already scarce resources. While a good step towards helping former foster youth gain independence, many of these programs are extremely basic and temporary. Most housing options are available in limited supply and do not go beyond 24 months. This means that if a youth gained a spot in a transitional housing program at the age of 18, they would be forced to leave subsidized housing at the tender age of 20. This would be especially difficult if a youth were balancing school, a job and needing to pay for market rate housing, which would include furnishings and rental deposit. Along with housing programs being extremely temporary, other services available through the state are simply not enough. There is no funding for transportation costs or emergency situations, such as car repairs or money for food. Former foster youth are expected to overcome too many years of instability and hardship with very little support from the state, which became responsible for their wellbeing the moment they were removed from their family home. 17 Aldana Just in Time for Foster Youth: Case Study Just in Time for Foster Youth (JIT) is a grassroots organization that began as the sole efforts of former child advocacy lawyer and San Diego resident, Jeanette Day in 2002. In her years as a lawyer in the San Diego’s juvenile court system, Day witnessed numerous foster youth exiting the system with very little support from caring adults to aid during their transitions from wards of the state to self-sufficient adulthood. JIT’s initial efforts began as homemade gift baskets put together by Ms. Day, Diane Cox (current Board President) and other concerned women whose intention was to provide basic household items to youth leaving foster care and venturing out on their own for the first time. Today, Just In Time for Foster Youth is a full-fledged 501(c)3 non-profit status corporation boasting a full-time staff but whose efforts still remain fundamentally energized by its many volunteers. Currently the organization’s efforts are compromised of five distinct programs aimed at providing both tools for self-sufficiency and assistance with basic necessities. They include the 1) Emergency and Basic Needs program, 2) My First Home program, 3) College Bound (Educational) Program, 4) Career Bound (Vocational) Program, and finally, 5) Financial Fitness Program. Developed in reaction to nationally recognized shortfalls for this target population and also in direct response to feedback provided by youth serviced, Just In Time’s programs are both innovative and unique in their approach. The idea behind Just In Time is to serve as an “extended family” to former foster youth and provide for them, much like a real family provides guidance and monetary support during a youths transition into independence. By tailoring their services to the individual and focusing on needs not met through traditional independent living 18 Aldana programs (what they call “gap services”), Just In Time manages to create an arena where youth can receive much needed support without the contingencies and limitations that they may encounter at other programs. Just In Time’s extended family model is at the heart of how the organization operates. Eligibility for services is available to any former foster youth between the ages of 18 to 26 regardless of duration of stay within the child welfare system and without consideration to what other programs or services the youth may be participating in simultaneously. The extended family model embraces all former foster youth who are striving at self-sufficiency by working, pursuing an education or both. Upon acceptance into any of the JIT programs, youth must agree to maintain the standards of eligibility (working and/or going to school) and submit to three requirements; they must complete the organizations Financial Fitness training, agree to receive assistance from at least one JIT mentor (called JIT Champions by the organization), and finally, the youth agree to complete yearly self evaluation surveys every year until they have graduated from the program or upon reaching age 27. A contributing factor to the extended family environment is the inclusion of former foster youth in the ranks of staff members. This vital element creates a symbiosis for staffers and serviced youth by enabling staff members to give back to their own community while also bringing an acute understanding of what being a youth in transition without familial support is like. Future plans are to eventually have the entire organization manned by former foster youth, an endeavor that is will help reinforce JIT’s commitment of creating a family type setting. This venture can only empower the foster youth community by producing role models for younger youth who have recently aged 19 Aldana out of the system, and by strengthening ties between serviced youth and organization staff members who will have a greater sensitivity when dealing with the youth. Youth are usually referred to JIT by other agencies or by word of mouth. When requesting help from the organization, youth must initially fill out an application for the individual program that is of interest. Each youth must fill out an intake form that will determine their eligibility (based on whether they are working, in school or both) and will also numerically rate the youth on a self-sufficiency scale that was assembled by JIT staff in order to help track the youth’s progress and impact (outcome) after having received JIT services. This scale determines self-sufficiency levels and program needs for individuals applying for services. The 6 categories used to measure self-sufficiency are; housing, education, employment, financial fitness, connection to a caring adult, and community service. Each category is scored from 1 (lowest) to 5 (highest). A combined score is used to determine an overall level of self-sufficiency or SS. These levels are labeled as In Crisis, At Risk, Safe, Stable and Thriving. Youth are also asked to rate themselves on overall self-sufficiency upon intake. See sample scale and diagram of self-sufficiency scale on page 21 (provided by JIT Board member in charge of outcomes, Dr. Patricia Benesh). This scale, along with the self-evaluation surveys serviced youth commit to filling out and returning each year, is an essential tool for JIT staff to determine whether their services are helping improve outcomes amongst their target population. 20 Aldana SAMPLE RESULTS: Self-Sufficiency (SS) Score: Based on 6 Program Component Levels (1=lowest-5=highest)* Sample Youth Outcome Showing 4 Years Component/Level Joe Entering Joe YR1 Joe YR2 Housing 1 2 3 Education 2 3 3 Employment 1 3 3 Finances 1 2 3 Connection 2 3 3 Service 1 2 3 SS SCORE** 1.3 2.3 3.0 SS LEVEL In-Crisis At-Risk Safe * Determined by online data collection ** Cumulative sum divided by 6 (the number of programs) Key: SS Rating System In-Crisis At-Risk Safe Stable Thriving 21 Aldana 1.0-1.9 2.0-2.9 3.0-3.9 4.0-4.4 4.5+ Joe YR3 Joe YR4 4 5 4 3 4 4 4.0 Stable 5 5 4 4 4 5 4.5 Thriving There are several ways that Just In Time’s efforts go beyond what is traditionally available through state and other federally funded programs. First of all, through their Emergency and Basic Needs program, youth can apply to receive funds for just about any situation imaginable. Requests by youth for Basic Needs have included money for car repairs, rental deposit, help with monthly bills, grocery gift cards for food, bus passes, money for school books, money for new clothes and even business attire donated for job interviews. Current program director and one time JIT recipient, Meredith Hall Praniewicz, once received money to obtain much needed reading glasses when she was having trouble viewing the board while attending classes at UCSD. These items are things that a former foster youth would never be able to obtain through the traditional avenues available to them. However, they are essential in making or breaking an already precarious attempt on the road to self-sufficient adulthood for these youth. Youth receiving check from JIT staff member. (source JIT website) Another highly utilized program available to the youth is the My First Home program. This program provides the youth with all the essentials that go into setting up into a new apartment or home. Items include gently used and new furniture, mattresses donated from a partnership with Sleep Train, pots, pans, towels, linens, 22 Aldana microwaves and even décor items. JIT volunteers and staff come together to help with the actual setup and delivery of the items to the youth’s new home. All items are collected via yearlong donations and through fundraisers conducted throughout the year by the organization. Furnishings donated by JIT. (source, JIT website) JIT’s College Bound Program provides youth with extensive tools to help make their college or educational venture a success. This program offers the youth a variety of academic essentials including computers, printers, software, books and school supplies while also providing furnishing for those moving into dorm rooms or college apartments. College Bound also connects the youth with a volunteer mentor that can serve as a valuable source of knowledge and support for the youth while in school. This program has an annual award ceremony where budget guidance is provided and tips on legal matters are available. Another exceptional program available at Just In Time is the Career Bound program that provides youth with up to $500.00 of educational or vocational tools along with pairing them with a volunteer mentor who is successful in their chosen profession. This program, also known as Career Horizons for Young Women, is currently only accessible to the female youth population because of funding issues, but will be expanding to include male youth in the near future. During its 6-month 23 Aldana long duration, youth learn skills and valuable information, including job shadowing from the various volunteers in this program. They are also exposed to different careers and introduced to new opportunities they might have never encountered otherwise. During my tenure as an intern at JIT, this program held a fashion show mixer at Macy’s in Fashion Valley. The youth and volunteers met to discuss proper business attire, including tips on hair, make-up and interviewing techniques, all important skills for successful job attainment. Youth receiving a laptop. (source JIT website) The last program, and the one I find the most innovative and exceptional, is the Financial Fitness Program. This program exposes the youth to ‘financial training’ that can include simple things like how to open a bank account, balance a check book or pay a bill to more advanced topics such as saving for your future and even investments. The remarkable part about this program is the ‘matched savings’ portion, which allows youth to receive up to $4,500.00 from JIT in matched savings. A youth who joins this program must save for 3 months consecutively until reaching one of the 5 different match modules (match modules are $250, $500, $750, $1000 and $2000). To receive the full $4,500.00 the youth must begin with the first module and proceed accordingly. A youth does have the option of skipping to one of the 24 Aldana higher modules first but this means they forfeit the lesser quantities. How this works is, a youth must save for at least consecutive months, upon reaching chosen module she/he brings in proof of savings in form of bank statement and is then matched by JIT staff upon discussion of what the funds are being used for. This program is one of the more important ones at JIT because it provides the youth with techniques on money management while also providing a wonderful incentive to do so. On the whole, Just In Time’s programs are different than any others available locally. They provide services to former foster youth that are tailored to the individual but fundamentally promote self-sufficiency by keeping the youth on track towards bettering their futures through education, career and other job skills, money management all in a warm and caring environment by people that have been in their same shoes. Economic Incentive for Helping this Community As a community it makes sense to help former foster youth for different reasons. First, as former wards of the state, they are essentially the responsibility lies within the community to ensure that these youth receive all the necessary tools to become welladjusted, successful contributing members of society. Another key incentive is the potential financial expenditures we may have to make as a community if we do not invest into this segment of our population. Here I will present average annual cost of an incarcerated person in California, average annual cost of a SSI/Welfare recipient and also look into homelessness costs and emergency medical treatments used by uninsured/homeless individuals in which the city ends up footing the bill. I will then present Just In Time’s annual expenditures. 25 Aldana Expenditures that help this population stay on their feet and on the path to selfsufficiency. JIT Assists 800 668 700 676 600 500 385 400 277 290 300 414 192 200 194 138 100 185 2006 2007 2008 Total Youth Assisted 2009 2010 Total Youth Assists $ JIT Budget $500,000 $450,000 $400,000 $350,000 $300,000 $250,000 $200,000 $150,000 $100,000 $50,000 $JIT Budget 26 Aldana 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 $104,000 $179,000 $277,000 $395,000 $453,926 Conclusion While the issues of insufficiently prepared youth leaving the foster care system will likely continue to be a problem as long as the child welfare system remains the same, we understand that there are people out there working on improving this population’s outcomes. Just In Time has found a niche for itself by providing services to youth not traditionally available via state and other local programs. By providing these ‘gap services’ to former foster youth and welcoming them into their ‘extended family’ model of operations they are doing a good service in helping increase their target populations level of self sufficiency. By measuring incoming levels upon intake they have also devised a tracking system to inform themselves whether their efforts are making an impact on the youth serviced. While the issue of securing housing is an important one for former foster youth, especially in the Southern California region where housing in general and affordable housing in particular remain elusive, unfortunately JIT does not provide it. However, their Emergency and Basic Needs Program ensure that youth who have secured a place to call home can stay in it even when facing hardships. Finally, I will talk about a recent assembly bill passed that extends foster care up to the age of 21. Youth can opt out of foster care any time after their 18th birthday, but have the option of returning to foster care anytime before their 21st birthday if they so choose. Appendix I plan on adding chart(s) on improved outcomes based on JIT surveys. I am having trouble accessing them, but I think they will be a good component to add. 27 Aldana Bibliography 1) Just In Time for Foster Youth. “Volunteers.” Retrieved October 17, 2011. http://www.jitfosteryouth.org/index.html 2) LEAP (Leadership Empowers All Possibilities) Council report. Released October 2011. Commission on Children, Youth and Families. www.sandiegoCCYF.org 3) U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Foster Care Statistics 2009. Child Welfare Information Gateway, May 2011, page 5. http://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/factsheets/foster.cfm 4) Osgood, D. Wayne. "The Transition to Adulthood for Youth “Aging Out” of the Foster Care System." On your own without a net: the transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2005. page 27. Print. 5) Nixon, Robin and Maria Garin Jones. Child Welfare League of America report. Improving Transitions to Adulthood for Youth Served by the Foster Care System: A Report on the Strengths and Needs of Existing Aftercare Services. 2000. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. 6) THP-Plus brochure. “Transitional Housing Program for Emancipated Foster/Probation Youth”. Produced and published by California Department of Social Services. 7) The Fleecing of Foster Children: How We Confiscate Their Assets and Undermine Their Financial Security. Published by the Children’s Advocacy Institute, First Star and University of San Diego Law School. Report, 2011. 8) Transitions: Building Better Lives for Youth Leaving Foster Care. Childrens Action Alliance. Report, 2005. 9) Connected by 25: A Plan for Investing in Successful Futures for Foster Youth. Prepared by The Youth Transition Funders Group Foster Care Work Group with The Finance Project. Report, 2007. 10) Expanding Transitional Services for Emancipated Foster Youth: An Investment in California’s Tomorrow. Published by Children’s Advocacy Institute. Funded by A California Wellness Foundation. Report, January 2007. 11) Home Again: Ending Chronic Homelessness in San Diego. “Project 25.” Retrieved October 17, 2011. http://homeagainsd.org/our-progress/project-25 12) Duncan, Brian and Laura Agys (2007). Economic Incentives and Foster Care Placement. Southern Economic Journal. (pgs.114-142) 28 Aldana