War Powers Act Summary

advertisement

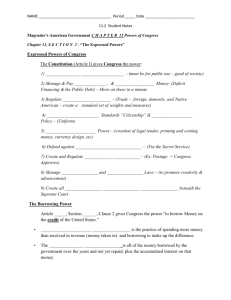

WAR POWERS ACT Overview This guide is intended to serve as an introduction to research on the War Powers Resolution, Public Law 93-148, 87 Stat. 555, passed over President Nixon's veto on November 7, 1973. The War Powers Resolution is sometimes referred to as the War Powers Act, its title in the version passed by the Senate. This Joint Resolution is codified in the United States Code ("USC") in Title 50, Chapter 33, Sections 1541-48. The term "Resolution" can be misleading; this law originated as a Joint Resolution and was passed by both Houses of Congress pursuant to the Legislative Process, and has the same legal effect as a Bill which has passed and become a law. For more information on Bills and Joint Resolutions see this explanation of Congressional Forms of Action. The Constitution of the United States divides the war powers of the federal government between the Executive and Legislative branches: the President is the Commander in Chief of the armed forces (Article II, section 2), while Congress has the power to make declarations of war, and to raise and support the armed forces (Article I, section 8). Over time, questions arose as to the extent of the President's authority to deploy U.S. armed forces into hostile situations abroad without a declaration of war or some other form of Congressional approval. Congress passed the War Powers Resolution in the aftermath of the Vietnam War to address these concerns and provide a set of procedures for both the President and Congress to follow in situations where the introduction of U.S. forces abroad could lead to their involvement in armed conflict. Conceptually, the War Powers Resolution can be broken down into several distinct parts. The first part states the policy behind the law, namely to "insure that the collective judgment of both the Congress and the President will apply to the introduction of United States Armed Forces into hostilities," and that the President's powers as Commander in Chief are exercised only pursuant to a declaration of war, specific statutory authorization from Congress, or a national emergency created by an attack upon the United States (50 USC Sec. 1541). The second part requires the President to consult with Congress before introducing U.S. armed forces into hostilities or situations where hostilities are imminent, and to continue such consultations as long as U.S. armed forces remain in such situations (50 USC Sec. 1542). The third part sets forth reporting requirements that the President must comply with any time he introduces U.S. armed forces into existing or imminent hostilities (50 USC Sec. 1543); section 1543(a)(1) is particularly significant because it can trigger a 60 day time limit on the use of U.S. forces under section 1544(b). 1 The fourth part of the law concerns Congressional actions and procedures. Of particular interest is Section 1544(b), which requires that U.S. forces be withdrawn from hostilities within 60 days of the time a report is submitted or is required to be submitted under Section 1543(a)(1), unless Congress acts to approve continued military action, or is physically unable to meet as a result of an armed attack upon the United States. Section 1544(c) requires the President to remove U.S. armed forces that are engaged in hostilities "without a declaration of war or specific statutory authorization" at any time if Congress so directs by a Concurrent Resolution (50 USC 1544). Concurrent Resolutions are not laws and are not presented to the President for signature or veto; as a result the procedure contemplated under Section 1544(c) is known as a "legislative veto" and is constitutionally questionable in light of the decision of the United States Supreme Court in INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983). Further sections set forth expedited Congressional procedures for considering proposed legislation to authorize the use of U.S. armed forces, as well as similar procedures regarding proposed legislation to withdraw U.S. forces under Section 1544(c) (50 U.S. 1545-46a). The fifth part of the law sets forth certain definitions and rules to be used when interpreting the War Powers Resolution (50 USC 1547). Finally, the sixth part is a "separability provision" and states that if any part of the law is held (by a court) to be invalid, on its face or as applied to a particular situation, the rest of the law shall not be considered invalid, nor shall its applicability to other situations be affected (50 USC 1548). U.S. Presidents have consistently taken the position that the War Powers Resolution is an unconstitutional infringement upon the power of the executive branch. As a result, the Resolution has been the subject of controversy since its enactment, and is a recurring issue due to the ongoing worldwide commitment of U.S. armed forces. Presidents have submitted a total of over 120 reports to Congress pursuant to the Resolution. Some examples of the Resolution's effect on the deployment of U.S. armed forces include: 1975: President Ford submitted a report to Congress as a result of his order to the U.S. armed forces to retake the Mayaguez, a U.S. merchant vessel which had been seized by Cambodia. This report is the only report to have cited Section 4(a)(1) (50 USC Sec. 1543(a)(1)) of the Resolution, triggering the 60-day time limit; however the operation was completed before 60 days had expired. 1981: President Reagan deployed a number of U.S. military advisors to El Salvador but submitted no report to Congress. Members of Congress filed a federal lawsuit in an attempt to force compliance with the Resolution, but the U.S. District Court hearing the suit declined to become involved in what the judge saw as a political question, namely whether U.S. forces were indeed involved in hostilities. 2 1982-83: President Reagan sent a force of Marines to Lebanon to participate in peacekeeping efforts in that country; while he did submit three reports to Congress under the Resolution, he did not cite Section 4(a)(1), and thus did not trigger the 60 day time limit. Over time the Marines came under increasing enemy fire and there were calls for withdrawal of U.S. forces. Congress, as part of a compromise with the President, passed Public Law 98-119 in October 1983 authorizing U.S. troops to remain in Lebanon for 18 months. This resolution was signed by the President, and was the first time a President had signed legislation invoking the War Powers Resolution. 1990-91: President George H.W. Bush sent several reports to Congress regarding the buildup of forces in Operation Desert Shield. President Bush took the position that he did not need "authority" from Congress to carry out the United Nations resolutions which authorized member states to use "all necessary means" to eject Iraq from Kuwait; however he did ask for Congressional "support" of U.S. operations in the Persian Gulf. Congress passed, and the President signed, Public Law 102-1 authorizing the President to use force against Iraq if the President reported that diplomatic efforts had failed. President Bush did so report, and initiated Operation Desert Storm. 1993-99: President Clinton utilized United States armed forces in various operations, such as air strikes and the deployment of peacekeeping forces, in the former Yugoslavia, especially Bosnia and Kosovo. These operations were pursuant to United Nations Security Council resolutions and were conducted in conjunction with other member states of NATO. During this time the President made a number of reports to Congress "consistent with the War Powers Resolution" regarding the use of U.S. forces, but never cited Section 4(a)(1), and thus did not trigger the 60 day time limit. Opinion in Congress was divided and many legislative measures regarding the use of these forces were defeated without becoming law. Frustrated that Congress was unable to pass legislation challenging the President's actions, Representative Tom Campbell and other Members of the House filed suit in the Federal District Court for the District of Columbia against the President, charging that he had violated the War Powers Resolution, especially since 60 days had elapsed since the start of military operations in Kosovo. The President noted that he considered the War Powers Resolution constitutionally defective. The court ruled in favor of the President, holding that the Members lacked legal standing to bring the suit; this decision was affirmed by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. See Campbell v. Clinton, 203 F.3d 19 (D.C. Cir. 2000). The U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal from this decision, in effect letting it stand. 2001: In the wake of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Congress passed Public Law 107-40 (PDF), authorizing President George W. Bush to "use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or 3 harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons." For the first time, "organizations and persons" are specified in a Congressional authorization to use force pursuant to the War Powers Resolution, rather than just nations. 2002: Congress authorized President George W. Bush to use force against Iraq, pursuant to the War Powers Resolution, in Public Law 107-243 (PDF). Under the United States Constitution, war powers are divided. Congress has the power to declare war, raise and support the armed forces, control the war funding (Article I, Section 8), and has "Power … to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution … all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States, or in any Department or Officer thereof", while the President is commander-in-chief of the military (Article II, Section 2). It is generally agreed that the commander-in-chief role gives the President power to repel attacks against the United States and makes the President responsible for leading the armed forces. In addition and as with all acts of the Congress, the President has the right to sign or veto congressional acts, such as a declaration of war. During the Korean and Vietnam wars, the United States found itself involved for many years in situations of intense conflict without a declaration of war. Many members of Congress became concerned with the erosion of congressional authority to decide when the United States should become involved in a war or the use of armed forces that might lead to war. The War Powers Resolution was passed by both the House of Representatives and Senate but was vetoed by President Richard Nixon. By a two-thirds vote in each house, Congress overrode the veto and enacted the joint resolution into law on November 7, 1973. Presidents have submitted 130 reports to Congress as a result of the War Powers Resolution, although only one (the Mayagüez incident) cited Section 4(a)(1) and specifically stated that forces had been introduced into hostilities or imminent danger. Congress invoked the War Powers Resolution in the Multinational Force in Lebanon Act (P.L. 98-119), which authorized the Marines to remain in Lebanon for 18 months during 1982 and 1983. In addition, the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 1991 (Pub.L. 102-1) which authorized United States combat operations against Iraqi forces during the 1991 Gulf War, stated that it constituted specific statutory authorization within the meaning of the War Powers Resolution. 4 On November 9, 1993, the House used a section of the War Powers Resolution to state that U.S. forces should be withdrawn from Somalia by March 31, 1994; Congress had already taken this action in appropriations legislation. More recently under President Clinton, war powers were at issue in former Yugoslavia; Bosnia; Kosovo; Iraq, and Haiti, and under President George W. Bush in responding to terrorist attacks against the U.S. after September 11, 2001. "[I]n 1999, President Clinton kept the bombing campaign in Kosovo going for more than two weeks after the 60day deadline had passed. Even then, however, the Clinton legal team opined that its actions were consistent with the War Powers Resolution because Congress had approved a bill funding the operation, which they argued constituted implicit authorization. That theory was controversial because the War Powers Resolution specifically says that such funding does not constitute authorization." Clinton's actions in Kosovo were challenged by a member of Congress as a violation of the Wars Power Resolution in the D.C. Circuit case Campbell v. Clinton, but the court found the issue was a non-justiciable political question. After the 1991 Gulf War, the use of force to obtain Iraqi compliance with United Nations resolutions, particularly through enforcement of Iraqi no-fly zones, remained a war powers issue. In October 2002 Congress enacted the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Pub.L. 107-243 which authorized President George W. Bush to use force as necessary to defend the United States against Iraq and enforce relevant United Nations Security Council Resolutions.[10] May 20, 2011, marked the 60th day of US combat in Libya (as part of the UN resolution) but the deadline arrived without President Obama seeking specific authorization from the US Congress.[11] President Obama, however, notified Congress that no authorization was needed, since the US leadership was transferred to NATO, and since US involvement is somewhat limited. On Friday, June 3, 2011, the US House of Representatives voted to rebuke President Obama for maintaining an American presence in the NATO operations in Libya, which they considered a violation of the War Powers Resolution. 5