Final Teaching Project- Using Google Docs to Peer Edit

advertisement

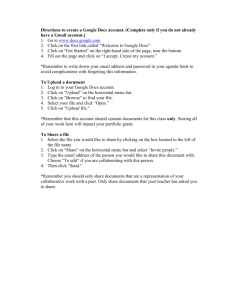

Using Google Docs to Peer Edit Elisabeth Slocum Michigan State University April 22, 2012 My First Thoughts Teaching the revision stage of the writing process to middle school students can be a difficult task, but technology can make that process much more bearable, even more effective. Hicks (2009) argues that using collaborative word processors allows students to move toward deep revisions that teachers hope to teach. I believe this deep revision is rarely witnessed in classrooms, but could be by using technology. Students are often afraid to be critical and don’t make constructive comments on their peers’ papers. Although peer editing can be a painful task, it is a worthwhile one. Peer conferencing helps students build on each other’s strengths, allows students to interact in their own language, builds self-confidence and provides students an opportunity to work on their communication skills (Parsons, 2001). Because editing includes all these components, it is such a beneficial activity. I wanted to help my students get better at it, and see the value in it. To do this, I thought it only made sense to use a tool that most students are already good at, technology. My school recently created G-mail accounts for all students, thus giving them access to applications such as Google Docs. I was just learning about Google Docs in my master’s class and thought this would be a perfect opportunity to implement what I was learning with the new technology at school. I also thought it would motivate students to get more involved because they are so familiar with communicating using technology. Students today are very concerned with constantly being in touch with each other and being connected (Sweeney, 2010). I knew this about my own students and thought using Google Docs would be a great way to introduce them to a new way to peer edit that would keep them connected to one another. My first goal in this project was to guide students to peer edit successfully by collaborating using a real life tool. I felt that many students didn’t value the editing and revising stages of the writing process and according to Stoddard and MacArthur (1993), emergent writers need to learn to revise. One important revision strategy is peer editing. I wanted students to work on their peer editing skills and to know what tools they needed to have when collaborating like this (Parsons, 2001). Students will need to be equipped with the skills necessary to work in a group for their future jobs (Karchmer, 2001). Many jobs require students to work as a team to accomplish a task. Much of this group work will involve collaboration and knowing how to perceptively give input and feedback. Simply saying “good job” to everyone in their future group will not get them far. When my students have peer edited in the past, that’s usually all I heard them say. I wanted them to be able to give constructive criticism, and reflect on their own ability to give feedback. My second goal was to incorporate technology into my classroom. Along with the ability to work in groups, students will need to be tech savvy and be web literate in their future careers (Ohler, 2009). Future employers of my students will expect them be able to work with people far away, thus needing to know how to use technology. Some companies have workers in two or three continents and employees will need to know how to use technology to function in the global market (Kellison, 2008). Our school has been doing a lot with technology and recently assigned every student a G-mail account, so using technology in the classroom is highly encouraged. I want my students to be prepared for their futures by having technology skills. Google Docs will allow students to work at a distance from each other (even though it will be just across the classroom) and have practice using the type of collaborative technology they will use in the workplace. Studies have found that when using Google Docs, there is a greater sense of ownership over the document and students believe revising the document made it better due to collaboration (Thomas, 2011). These were the results I hoped to get from my students. I wanted them to see the value in revising and collaboration using technology and Google Docs. I think that students will be excited as well as nervous to use Google docs. Teens today use technology to socialize and get feedback from others (Sweeney, 2010). Students are constantly communicating using technology, so by transferring this to the classroom, I think they will be more motivated and excited to peer edit in this way. I also think students will see the importance in this activity and find it easier to peer edit on a computer rather than in person. A study found that 85% of students associate writing with success in school. That same study also found that 50% of students think that writing is easier on a computer because it is easier to edit and revise (Jenkins, 2008). Usually peer editing does not serve much purpose because students don’t say anything too critical of their peer’s paper. By using Google Docs, I think students will be more inclined to give constructive criticism because the computer puts a buffer between the writer and the editor and it will not be so difficult to give negative feedback (Hunter-Mintz, 2008). Giving peers negative feedback may make students nervous, but the use of this technology will make them excited to try it. I also hypothesize that students will have prior knowledge of the technology and will want to use Google Docs in other areas of their lives. Hunter-Mintz (2008) suggests that it is important to help students see the value of language arts tools outside of the language arts classroom. This can be done by showing them how to use what we learn in language arts in other subjects. I think my students will see that they can use Google Docs in other subjects as well. Even if it is just saving a document to Google Docs so they don’t have to remember a flash drive or using the chat room feature to discuss a math problem, the skills they learned in the language arts class will be extended to other areas of their lives. I also thought that I wouldn’t need to give much instruction as to how to use the technology because students are already so familiar with technology and use it constantly (Ohler, 2009). This would allow me to focus more on editing skills and not on how to use the technology. Those Who Would Be Joining Me and How it Would Go The students that I worked with were my seventh grade English Language Arts class. The class is made up of Caucasian, middle class students who, for the most part, love to write. I have these kids for two hours a day, first and fifth hours. First hour we spend on reading, fifth hour we spend on writing, so work with Google Docs and peer editing took place in fifth hour, right after lunch. We have about 50 minutes together each class period. By the time things like journal writing and homework collecting routines are done, we have about 40 minutes or so of good work time. The classroom is organized with table groups. I have six tables with three to four kids at each group. Before and during working with Google Docs, I had to discuss the responsibility that comes with the privilege of technology. For this unit, the technology would be the mini laptops to be used in our classroom. I started by going over how to use Google Docs, and how it saves student work to the “giant internet cloud in the sky” (that’s how I explained it to my students). Students figured out the chat feature pretty quick, so I had to explain that their privileges will be taken away if they are not using the technology properly. Most students were using the chat feature responsibly and I watched a few of them have group discussions about a peer’s paper, so my quick reminder of using the feature properly was effective and students did use it for the right reasons, not just to socialize. The instructional sequence was based on the perceived notion that students need practice with technology, collaboration and successful peer edit. I thought that, having experience with technology, they would need little training, just guidance (Ohler, 2009). My students constantly talk about how they text and use social networking websites, like Facebook, all the time. They have also had experience using word processing programs, like Word. I thought, with that kind of experience, they would need little instruction as to how to log on to Google Docs, how to create and share a document, and how to comment on a peer’s paper. In addition to working with technology, I knew that my students’ literacy needs included work on peer editing. So many students think that their first draft is good enough to be a final draft. They either don’t know how the writing process works, or don’t see the value in it. I wanted my students to appreciate and become successful at the editing and revising stage, specifically. Young writers need to be taught the writing process, including the editing and revising stage (Stoddard & MacArthur, 1993). Although this paper only focuses on the editing stage, I taught the whole writing process based on collaboration. I had noticed that my students really enjoyed talking about their stories and did a good job of building off each other. Our genre focus was mystery writing, and the students constantly talked about crimes, clues, and detectives with each other. During our pre-writing stage, I had a pair of students get the idea to write the same story, but from two different perspectives, so this required a lot of collaboration. Atwell supports this when she talks about how students also need social interaction to be engaged (Atwell in Stemper, 2002). I based my instruction on this idea of collaboration and how my students were already good at it, just needed some direction as to how to channel that collaboration to successful peer conferences. I continued to base my instructional sequence on knowing my students’ literacy needs included being able to move away from simple, positive feedback during peer editing and go beyond the surface level comments to really get the benefits of peer editing (Perry & Smithmier, 2005). When peer editing, I hear and see a lot of “that’s good” and “no changes are needed.” I want my students to understand that a paper can always be better and that their input is appreciated and needed in their peers’ papers. I wanted them to be able to see that changes can be made, and give alternate ideas for the parts that require work. In order to be prepared for the real world, my students need practice with real life situations using social network tools and working with a group (Lombardi in Miller, 2009). Most jobs will require students to work as a team to get a task completed. This collaboration will more than likely include technology. One of the last ideas I based my instruction on was knowing how my students needed a way to access their documents from various places without having to remember their flash drive, which almost always seemed to be left at home or in a locker, or lost! Google Docs would allow students to access their stories from anywhere (Jensen, 2010). I based my instructional sequence on the needs mentioned above. I knew I would need to briefly review some things, and model and teach others. My students had some practice with peer editing earlier in the year, so I planned on reviewing that after we went over Google Docs and the technology part, which was the part I was most apprehensive about never having taught using Google Docs before. I created a how-to guide for Google Docs by making screen shots and captions (see Appendix). I thought this would help students go through the process of getting their stories into Google Docs and then sharing them. From there, I wanted to focus on peer editing and the purpose of peer editing in this new way. I didn’t think the technology part would take very long since I figured students would figure it out based on prior experience. I wanted to spend more time on making quality comments on their peers’ papers. The Plans Day One Daily Objectives Students will be able to demonstrate their ability to sign into Google Docs and create a document Students will be able to demonstrate their ability to share their mystery with at least two other students Students will be able to construct comments on a peer’s mystery using Google Docs features Students will be able to analyze their peer’s paper for mystery elements Order of Events 1. Students will respond to journal prompt in their journal. The prompt is to respond to the novel we read in 1st hour. 2. I will take attendance as students work on their journal. 3. As students finish up their journal, I will pass out the Google Docs How To sheet and the Peer Feedback Grading Rubric (see Appendix). 4. I will ask students if they want to share their journals. A few will probably share and we will talk about their responses. 5. I will ask them to put their journals away and take a look at the sheets I passed out. I will tell them that I will be going through the steps on my computer and they can follow along with the projector, but the how to sheet may come in handy if they get lost or for later. I will tell them about Google Docs and how they can now access their story from anywhere and that they don’t need a flash drive or anything else. I hope they will find that to be stress relieving (Jensen, 2010). I will also go over the rubric and tell them what kind of peer editing comments I am looking for. I know that it will be essential for students to give quality feedback and go beyond just grammar and spelling if it was going to improve writing (Perry & Smithmier, 2005). We will discuss these and questions students have. 6. I will have students go up by table to get their mini laptops as I turn on the projector and bring up the Internet. 7. I will go through the steps to bring up the homepage, log into Google Apps, how to create a document, and how to share it as the students do the same on their laptops. 8. I will walk around the room as students go through this process. 9. When students have their stories loaded into Google Docs, I will show them how to make comments on their peer’s paper. I will use the rubric to model what a good comment looks like (Hunter-Mintz, 2008). 10. Students will then read through their partner’s paper and make comments for the remainder of the hour, keeping in mind the grading rubric and what kind of comments they should be making. 11. As students do this, I will be walking around the room getting informal feedback and assessment by what kinds of comments the kids are saying and how they are using Google Docs. 12. With a few minutes before the bell rings, I will ask students how they are doing and what they think and we will briefly discuss the process so far. 13. I will have students shut down their computers and bring up them by table to put them away. Assessment The assessment for today will be informal and take place through my conversations with students individually and as a class. Day Two Daily Objectives Student will be able to recall how to log into Google Docs Students will be able to construct meaningful comments on peer’s papers Students will be able to identify and critique mystery elements in their peer’s paper Order of Events 1. Students will respond to a journal prompt in their journal. The prompt will be about their feelings about Google Docs so far. 2. I will take attendance as students write in their journals. 3. After students are done writing, I will ask them to share. We will talk about their experience yesterday and any changes that need to be made for today. 4. I will have students come up by table to get their laptops. 5. Students will open their peer’s story from yesterday and continue to read and peer edit. If they get done with one story, they can have another peer share with them and edit another story. Again, they will be using the rubric and checklists provided to make meaningful comments (Parsons, 2001). 6. I will walk around the room and talk to students and watch the kinds of comments they are making on their peer’s papers. 7. At the end of the hour, I will have students share their experiences, thoughts, and concerns. We will talk about using Google Docs and what they think about it. 8. Students will come up one table at a time to put their computers away. Assessment Assessment will be done through the use of a grading rubric (see Appendix) and my conversations with students. Day Three Daily Objectives Students will be able to analyze comments made on their paper Students will be able to incorporate comments into their paper Students will be able to assess their use of Google Docs Students will be able to assess their peer editing skills Oder of Events 1. Students will respond to a journal prompt about the novel we read in first hour. 2. I will take attendance as students write in their journals. 3. As students finish, they will share their journals. 4. As students put their journals away, I will tell them that they will be self-assessing their peer editing skills, taking a survey about Google Docs, and reading over peer comments today. I will go over how they should open the documents I shared with them via Google Docs and how they should complete the self-assessment and the survey (see Appendix). I want students to value the work they did and think about what they can do better next time (Parsons, 2001). Then, they will edit and revise their own paper using peer’s comments. 5. Students will come up by table to get their mini laptops. 6. As students work, I will walk around the room and talk with them individually and look at the comments that were made. 7. At the end of the hour, I will make sure every student has shared the self-assessment and survey with me and we will briefly talk about the process. 8. Students will come up by table group to put laptops back. Assessment I will grade student comments using the grading rubric I gave them on the first day. My Second Thoughts Students are very concerned about staying connected with each other (Sweeny, 2010) and this was very evident in my classroom as my students figured out the chat room feature of Google Docs much quicker than I anticipated. And this was just one of the unexpected interferences in my lesson plans that made it last 4 days instead of 3. I will begin by saying that overall, it was an extremely beneficial and helpful project to do with my students. I will also say that it was a learning experience for all involved. My students had never used Google Docs before and I had never taught it, and was just getting familiar with it myself when we began. I had hypothesized that students would catch on quickly to using Google Docs because they were already familiar with technology. Most students did catch on quickly, but some had technological difficulties. Their mystery stories were saved in a Word document that they had to copy and paste into Google Docs, a process that I thought would take about five minutes. This ended up taking some students half of the hour to complete. Some computers were going slow, some couldn’t find the right website, some were just confused all together. I planned on students really relying on the handout I created with screenshots. Very few even looked at the handout. Most students followed along as I went through the process on the projector. If they had a problem, they raised their hands until I came around and helped them. This made for a slightly more chaotic setting than I was planning on. Reflecting now, I should have insisted that they try the handout first, and if they were still having problems, then ask me. But, I just ran around like mad trying to help every student. Class ended with students being at various stages, something I was not planning on. I felt a lot of frustration from the students. We all realized this wasn’t going quite as planned. The next day started with a review of the previous day so students would remember how to log on to Google Docs and how to share with their peers. This went much smoother than the previous day. Students were still having some difficulties with technology, but enough of them understood it that they could help each other. This allowed students to focus more making comments on a peer’s paper. I felt like I wasn’t able to teach as much about the types of comments I wanted to see from my students because I was still trying to help several of them get to the point of commenting, so I reassessed my lesson for the next day and decided to extend the project. I figured all students would be ready to peer edit by the following day, so I put together a peer editing sheet with questions that I wanted students to ask themselves as they peer edited (see Appendix). The following day, I went over this with my students before they began peer editing. This went well because very few students were actually to the peer editing phase so it was a good transition from learning Google Docs to focusing on peer editing. I went over how I wanted my students to be specific and give constructive criticism. We talked about how one of the benefits of using Google Docs was that they didn’t have to be so afraid to be critical because the computer put a distance between the writer and the editor (Hunter-Mintz, 2008). By adding this extra discussion and focusing on how to peer edit, students did a much better job with their commenting and editing. The room was really quiet that day as students read through papers and made meaningful comments. If they got done, they would ask someone else to share his or her paper with them. It was a really cool thing to watch my students get so involved and actually asking for more papers to peer edit. They were definitely much more motivated, which I had hypothesized that they would be. I also assumed that students would value this because studies show that students associate writing with success. They wanted more feedback because they wanted to be better writers. On the second day before I had reassessed my plans, student journal responses reflected a lot of frustration with Google Docs from the previous day. This prompted a discussion about why we were using the application. I told my students my rationale for them using Google Docs, which is something I should have done in the first place. I told them that I wanted them to gain experience with a technology that they will likely use in their future careers, or something similar. I told them how many jobs today require employees to communicate and collaborate with people far away, so applications like Google Docs is extremely important to know how to use. I also told them that I wanted to make sure they were giving meaningful comments on their peer’s papers, and with the computer to put a distance between them and their peer, I thought that might motivate them to make better comments. The next days were so much more productive than the first, I wish I would have started out with that conversation. The last day ended with a survey of Google Docs and self-assessment of peer editing. I shared these documents with my students using Google Docs (see Appendix). I had hoped to do everything via Google Docs to really show my students the capabilities of the application. So I had my students all open the document and begin to take the survey. All at once there was a commotion. I didn’t realize that all my students would be on the same document. For some reason I thought they would all have their own survey and be able to take it individually. So, after I calmed them down, I asked if they could all go to the bottom of the survey and just type a few sentences. I thought maybe they could collaborate and create some kind of paragraph with their combined thoughts. This, too, created chaos and wasn’t working. So, I printed off the survey and self-assessment and had my students take it with a pencil. It was definitely a learning experience and my students were great sports about it. The Good, the Bad, and the Really Awesome Student participation and feedback was overall very positive. I can’t count the number of times I heard students yell across the room, “Hey so-and-so, will you share your story with me?” It was awesome. The only negative aspect was the frustration when the computers were going slow and when students typed in a peer’s email address wrong so the story didn’t get to them, but that didn’t last long. One thing I was most impressed with was student ability to work together to edit a peer’s paper. The screenshot below was taken of one student’s paper. On the side, three other students have a dialogue to help the student work on a specific part of his paper. One of the aspects of this comment thread I like is how students used their own language. They didn’t feel pressured to use fancy language, but used words they would use when using other technology. I also like the meaningful comments they made. Student 1 began a comment thread about the paper needing more explanation. Student 2 agreed, and added that the whole story needed more description. Student 3 contributed that the story was choppy. This collaboration is likely to be used in their future schooling and jobs as businesses focus on collaboration (Kellison, 2008). These were exactly the kinds of comments I was hoping to glean from my students. The students moved beyond basic spelling and grammar and focused on things like description and choppiness (Stoddard & MacArthur, 1993). In her survey after using Google Docs, Student 1 mentioned that it was easier to criticize the person on a computer than face to face. She also mentioned in her survey that the process of using Google Docs was pretty easy and that she would probably use Google Docs again. Student 1 is not always the most motivated student. I was really impressed by her ability and the effort she put into her comments. I think this had a lot to do with the use of technology. Like she mentions in her survey, it was easier when she didn’t have to see the person she was commenting about face to face, as was suggested by Hunter-Mintz (2008). With her comments, Student 1 exhibits one way that my goals were met. I wanted students to become familiar with technology and I wanted students to have more meaningful peer editing experiences. The next screenshot is from another student’s paper. The comments on the side show two students working together to edit the story. Student 4 focuses on the story elements we have been talking about in class. He mentions character description, word choice, and the mystery element of crime, all of which we have spent a lot of time on in class in the drafting stage of the writing process. I hoped students would use these skills in their peer editing, and Student 4 demonstrates that he did. This also shows that Student 4 is making the author aware of the audience’s needs (DiPardo & Freedman, 1988). Although this wasn’t something I meant to focus on, I was definitely glad my students took it to that level. He also works with Student 5 in this part of the paper to help his peer. On his survey, Student 4 said that peer editing with Google Docs was more fun than regular editing. Student 4 is very easily distracted in class and is usually late turning in assignments. While peer editing with Google Docs, he was constantly on task, reading multiple papers, and making good comments. He also collaborated with another peer to edit this paper. He demonstrates that my goals were met as well. He was much more motivated to do peer editing with technology than the “regular way” and made quality comments as a peer editor. That increased motivation was a factor I expected would happen (Hunter-Mintz, 2008). Students involved in the peer editing above also made use of the chat room feature. This caused me to go into a little bit of a mini lesson on appropriate use of technology. I told students that with the privilege of technology come more responsibility. Most students used the chat room to talk about their papers. It was a very successful tool for them. Unfortunately, not all students made meaningful comments. Some students still couldn’t get away from focusing on spelling and grammar. The following screenshot reflects an aspect of peer editing that I would like to make better next time I teach this lesson. I hope to get all my students working together and making meaningful comments, unlike the ones below. Student 6 does not focus on story elements or collaborate with others. She is a very capable writer and definitely knows her spelling and grammar, but she didn’t quite move beyond the surface level peer editing. She did, however, really utilize the highlighting feature, which met my goal of students using Google Docs editing features. Next time I do this lesson, I want more students to move beyond the above type of comments and focus on deeper and more meaningful revisions. Student 6 was one of the first ones to grasp Google Docs and get her comments done. She read multiple papers and mentioned on her survey that she liked using Google Docs to peer edit and that she would use Google Docs again, so I don’t think she was resisting the technology or not understanding the assignment. Although I would not classify Student 6 as a low ability writer, she does meet Stoddard and MacArthur’s (1993) description of a less skilled writer because she doesn’t move beyond mechanical errors. I’m afraid I may have rushed some students to get their comments done, thus resulting in less meaningful comments. Next time I will need to plan on more time and modeling to get better comments from them. Student 6 reveals how my technology goal was met, but not my peer editing goal. Overall, using Google Docs to peer edit was a very successful lesson for both my students and myself. I think I got more participation out of my students than I would have by using traditional peer editing with paper and pencils. After the initial confusion and frustration, students were really into using Google Docs and excited about the possibilities. I also teach Social Studies and since this lesson on Google Docs, I have had many students in Social Studies use the tool to send projects to themselves, which was something I had hoped would happen. The chat room feature was a highlight for many students and overall, it was productive for them. There were some students that needed to be reminded of what they were supposed to be doing with the chat feature, but most were able to handle it. Being able to handle that responsibility was a good lesson for them. They collaborated with each other on another peer’s paper, which is something I hadn’t exactly intended or taught them to do, as I was looking to just help them work together one-on-one, but the collaboration worked out really well. Most students not only were more motivated to peer edit, but made really meaningful comments. Appendix GOOGLE DOCS HOW-TO SHEET On the school homepage, click on Student Email on the left hand side of the page. Sign in using your username and password. Click on Docs. Click on Create. Click on Document from the drop down menu. This should open a new window that will look like the one below. Paste your story into the document. After your story is pasted in the document, click on File. Select Rename and name your story YourLastName_mystery. Like this Spinner_mystery. After your story is renamed, click on Share. Peer Editing Guidelines that was shared with students via Google Docs (adapted from Parsons, L. (2001). Revising and editing: Using models and checklists to promote successful writing experiences. Ontario, Canada: Pembroke Publishers.) QUESTIONS TO CONSIDER WHEN PEER EDITING Read through the following list of questions when you are peer editing. Every time you peer edit, take 2 questions and really try to work on that part of peer editing. Reflect on how well you are editing as you read your peer’s paper. During peer editing, how often do you: 1. show appreciation for specific, positive parts of writing? 2. make the writer feel worthwhile, even though you are being critical? 3. suggest alternate ideas in areas you think need work? 4. offer facts and reason to support you opinions? 5. use language that will allow the author to understand what you are thinking? 6. re-examine your own opinions and adjust them if another person comes up with a better idea? 7. reply freely to the writer’s questions or concerns? Google Docs Peer Edit Self-Assessment(adapted from Parsons, L. (2001). Revising and editing: Using models and checklists to promote successful writing experiences. Ontario, Canada: Pembroke Publishers.) PEER CONFERENCE SELF ASSESSMENT Skills I think I applied well: ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ I applied these well because: Skills I hope to improve next time: ____________________________ ____________________________ ____________________________ To improve these skills, I could: Google Docs Survey GOOGLE DOCS SURVEY Rate the following on a scale from 1 to 10, 1 being you agree the least and 10 being you agree the most: 1. Learning how to open and sign into Google Docs was easy. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 2. Learning how to create documents in Google Docs was easy. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 3. Learning how to share documents in Google Docs was easy. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 4. Learning how to open and view other people’s documents was easy. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 5. Commenting on and editing people’s papers was easy. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 6. I had never used Google Docs before. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 7. Using Google Docs to peer edit was better than peer editing “the old fashion” way. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8. I would use Google Docs again. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 9. What was your favorite part about peer editing with Google Docs? 10. What was your least favorite part about peer editing with Google Docs? Annotated Bibliography Ohler, J. (2009). New-media literacies. Academe, 95(3), 30-33, 5. This article reflects on the teacher’s role in using technology in the classroom. The author argues that being literate means being able to read and write using the latest and most recent forms of media, according to society. In today’s society, that means being able to read and write using internet resources such as graphics and moving images. With new technology, students are able to work together on a text as well as publish it. While students are really knowledgeable about technology, they need direction on how to use it effectively and making sure their writing is well done. The article gives a brief history of literacy, arguing how at one time literacy was in the hands of the elite only, but today, it is rapidly spreading. With new technology, web literature is within reach of almost everyone. When students go to enter higher education or the work force, they will be viewed as uneducated and not able to function if they aren’t web literate. While it is important that students are equipped with skills for this new literacy, instructors are hesitant to use it in the classroom because they are unfamiliar with it. The article suggests some ways instructors can implement technology and web literacy into the classroom with ease. One way is through the use of blogfolios. The author speaks from his own experience and says that his students are usually unfamiliar with blogging, but pick it up quite quickly because they have digital skills already. He has his students keep all their work in these blogfolios throughout the course. Blog writing requires different skills that those required when writing an essay. These digital writing skills will be necessary in the work place. The author continues to talk about blog content as well as media presentations. These types of literature require different, and necessary, skills. Karchmer, R. (2001). The journey ahead: Thirteen teachers report how the internet influences literacy and literacy instruction in their k-12 classrooms. Reading Research Quarterly, 36(4), 442. This article provided valuable insight on the use of the internet in the classroom. The author begins by arguing there is an obvious connection between technology, literacy, and literacy instruction. This argument is supported by historical examples. The author quotes other authors when she says that the internet has changed the definition of literacy by students no longer being only exposed to written text, but instead, read and write electronically. Students will be expected to use this new kind of literacy when they go to higher education or the work place and are expected to use the internet for a variety of purposes. The article was written almost 10 years ago and the author correctly predicted that communication will need to be quick and efficient as the world transitions to an informational economy. In order to be ready for this world, students will need to be able to use the internet to accomplish these communication skills. Another key skill in an informational economy is to be able to work with others no matter how far away they are. This skill will be crucial to businesses. The days when people had to meet in person to accomplish anything are gone. Students will enter jobs in which they work with people in other countries to accomplish a project. In order to be ready for these types of jobs, students must have instruction with these types of programs and the skills needed to use them effectively. It only makes sense to use this kind of instruction in the classroom because, as the author mentions, it encourages active learning. Finally, the author brings up the writing process and says that the use of the internet allows the writing process to be interactive. This idea is very exciting for the writing teacher because it will allow students to use technology they are already using in an educational way that will prepare them for their futures. Stoddard, B., & MacArthur, C. A. (1993). A peer editor strategy: Guiding learning-disabled students in response and revision. Research in the Teaching of English, 27(1), 76-103. Even though this article focused on learning disabled students, many of the ideas and strategies suggested would benefit any student. The authors conducted a survey that taught editing and revising strategies. To begin with, the authors stated their arguments for this study. They said that the revising stage is an important one and emerging writers need to learn it and currently, many lesser skilled writers only correct mechanical errors during this phase, not writing quality. The authors argue that students need goals, knowledge, skills, and strategies in order to be able to revise well. In addition to these needs, students also benefit from having the teacher model effective revising and gradually giving less support as students become capable of revising on their own. The article focused on teacher instruction, saying that peers working to edit each other’s papers is useless without teacher guidance. They do say, however, that peers working together to revise provides an audience the student already knows. They say that by having peer response groups, three provisions are given. First, there is peer interaction. Second, students take on and switch between the roles of author and editor. Finally, students are given the opportunity to find a problem in a text, put it into words, and then offer suggestions on how to fix this problem. These skills are very important. In the study, students were given instruction on how to revise another paper. Then, students worked in pairs. The author read his or her paper out loud while the editor offered feedback, then the editor reread the paper, writing comments on the paper. Then, the two students discussed the revisions. Students then worked independently to make changes on their own papers. To assess the papers, the authors looked at, among other factors, the change in quality between the two drafts. They noted an increase in quality when this peer revision method was used with students. Hunter-Mintz, K. (2008). Using technology in middle grades language arts: Strategies to improve student learning. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education. This book discusses various aspects of technology in the classroom, and only a few chapters were specifically useful for the theme of this paper. Chapter 6 is about cyber composition, the focus of this paper. The author recommends using technology for all parts of the writing process. The section on drafting suggested that technology allows students to create multiple drafts without having to rewrite every single word, which can be painful process. The author also suggests that peer editing can be made through the comment function on a word processor. The student can highlight a section of text and insert a comment that will appear in the margin of the paper. This may allow for more meaningful feedback because the peer editor doesn’t have to give criticism face to face. Chapter 11 focuses on a variety of web tools. The author mentions the use of rubrics and how they don’t necessary require a single right answer, but allow for a variety of responses. This is helpful for differentiated instruction and to help students understand what it expected of them. The author continues to suggest that the rubric be presented to the student along with an example of the product. This type of modeling makes sense so the expectations are clearly communicated to the student. The final chapter in the book discusses making the media matter. In it, the author discusses the correlation between technology and student motivation. Students are already familiar with technology, so it allows them to do something they are already good at in the classroom. Students are usually more motivated when technology is involved. Parsons, L. (2001). Revising and editing: Using models and checklists to promote successful writing experiences. Ontario, Canada: Pembroke Publishers. The focus of this book was how to help students edit and revise. The author lists some benefits of peer editing conferences, including offering the opportunity to build on each other’s strengths, ideas are suggested freely, students use their own language, students practice effective communication skills, and students feel like their opinion matters. These are benefits that every student needs and will help them in their future career as well. The author goes on to explain how to teach and use peer editing. Students can pick their groups freely, pick their groups with limitations, or have teacher assigned groups. There are benefits and fall backs to each method of group forming. After groups have been formed, students need to know how to give effective and purposeful feedback. A method suggested in the book is to use a checklist of questions for students to consider while peer editing. These questions include specific ways students should collaborate during a peer editing conference. The questions are about being specific, making the writer feel important, having support for opinions, and letting the other peer have a turn to talk. Another list recommended is a self-assessment of how the student did while peer editing. The assessment asks students to question what skills they feel they used well while peer editing and what skills they feel they want to improve for next time. The book provides several other checklists and guidelines for editing and revising, which are useful to give to students or have posted in the room as they are an easy way for students to recall how to edit and revise. References Campbell Hill, B., & Ekey, C. (2010). The next-step guide to enhancing writing instruction: rubrics and resources for self-evaluation and goal setting. (p. 148). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Chaka, C. (2011). Research on web 2.0 digital technologies in education. In M. Thomas (Ed.), Digital Education (pp. 37-59). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. DiPardo, A., & Freedman, S. W. (1988). peer response groups in the writing classroom: Theoretic foundations and new direction. Review of Educational Researc, 58(2), 119. Hicks, T. (2009). The digital writing workshop. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. Hunter-Mintz, K. (2008). Using technology in middle grades language arts: Strategies to improve student learning. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education. Jenkins, A. (2008). Report on teens, writing, and technology- full of surprises. The Hispanic Outlook in Higher Education, 18(18), 26-27. Jenson, T. (2010). No student email at school? Google Docs to the rescue. Library Media Connection, 28(6), 52. Kellison, K. (2008). Virtual teamwork. T.H.E. Journal,35(6), 22,24. Miller, R. (2009). Developing 21st century skills through the use of personal learning networks . (Doctoral dissertation, Northcentral University), Available from ProQuest. (3383118). Ohler, J. (2009). New-media literacies. Academe, 95(3), 30-33. Parsons, L. (2001). Revising and editing: Using models and checklists to promote successful writing experiences. Ontario, Canada: Pembroke Publishers. Perry, D., & Smithmier, M. (2005). Peer editing with technology: Using the computer to create interactive feedback. English Journal, 94(6), 23-24. Stemper, J. (2002). Enhancing student editing and revising skills through writing conferences and peer editing. (Master's thesis, Saint Xavier University), Available from ProQuest. (62289125)Retrieved from http://ezproxy.msu.edu.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com.proxy1.cl. msu.edu/docview/62289125?accountid=12598 Stoddard, B., & MacArthur, C. A. (1993). A peer editor strategy: Guiding learning-disabled students in response and revision. Research in the Teaching of English, 27(1), Sweeny, S. M. (2010). Writing for instant messaging and text messaging generation: Using new literacies to support writing. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 54(2), 121-130. Writer’s Memo The biggest factor that convinced me to make revisions was reading through this paper over and over, and consulting previous examples. The first time I write something, I usually write (or type) pretty fast to get all my ideas out. When I am done, I go back and read it and see all the mistakes I made. I read and reread several times to make it sound better. In the case of this project, it was extremely helpful to have example of previous students’ teaching project. At first, it confused me to see they were all formatted differently, but then I was reassured that this project was very flexible and needed to meet the needs of my goals, and that was all. Writing this has helped me think about how I will teach expository writing to my students in a number of ways. First, I think that it is so important to teach students good research strategies and techniques. Too often students get to college and are expected to research and they don’t know how. Students need to be familiar with knowing the difference between reliable and unreliable sources at the very least, and from there need strategies like how to come up with research topics, how to organize research, and how to use it in a paper. It made me think about my own process and how I can teach that to my students. It also made me think about the purpose of expository writing and who the audience is. I hope to publish my paper in some capacity at some point, so as I wrote, I was constantly thinking about my audience and what I wanted them to gain from this writing. I want my students to keep this in mind, too, because it impacts the language, examples, and ideas used in the paper. When my students write an expository piece, they, too, will have to research. They will have to develop research topics, know where to find sources, and think about how to use that research to support their arguments. From my experience in teaching this to my students already, I have noticed they struggle with this process. Although I have only taught this genre once, I realized teaching how to come up with research questions is a difficult concept to teach. I tend to find that part of my own writing easy because I know what I want to support and I know what topics I want to include. I think students are often overwhelmed with the idea that they can research anything and don’t know how to narrow it down. I also think that once students get their topics, they can find facts relatively easily, but when it comes to putting it all together in a paper, I think students run into problems. They don’t know how to use the research to support their arguments. They want to just sprinkle their paper with some quotes here and there and not really incorporate the research. By thinking about the process I used for this paper, I can help my students with this genre the next time I teach it. I learned that expository writing is, for me, easier than creative writing. I find it easier to write informative pieces than to use my imagination to write creative stories. I would rather quote experts and use APA formatting to cite my sources than rack my brain for adjectives to create imagery in a story. I used to love creative writing and I wanted to be an author. But, since college, I have grown to enjoy research and the learning that comes with it.