1905 russian revolution

advertisement

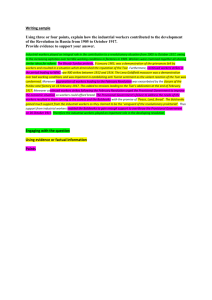

1905 RUSSIAN REVOLUTION 1856: End of Crimean war 1861: Emancipation of the serfs 1864: Zemstva set up; reform of judicial system 1881: 1 March: Alexander II assassinated 1893-1903: Witte as finance minister, industrialisation 1902-3: Peasant unrest 1904-5: Russo Japanese war 1905 22 Jan: ‘Bloody Sunday’ massacre 1905 August: Treaty of Portsmouth, ending war with Japan 17 Oct: Tsar’s October Manifesto 1905 Dec: St Petersburg and Moscow Soviets suppressed Tsar Nicholas II and family Violence & Nonviolence in 1905 • • • • 1905 is seen as an antecedent to the violent 1917 Russian Revolution which successfully ousted the Romanov dynasty. Lenin referred to 1905 as the “dress rehearsal” for 1917. Yet at the time it would have been seen as a valid attempt at revolution in itself, not merely a test run for the forceful and violent one to come. The years preceding the 1905 Revolution had seen great disruption and conflict within the Russian government and people. The regime refused to recognise the dire need for change in Russia and this failure to act was perhaps the main means by which tsarism prepared its own downfall. The 1905 revolution was driven forward by the – often spontaneous – impulse the grass roots gave it, and was a key part of the struggle of ordinary Russians to loosen government control in the only way they could in the face of ruthless repression, through the tools of nonviolence. Though the people engaged in some violence arising as part of protests and peasants tended to riot, and though at its points of weakness the government did promise the people concessions, the underlying relationship was non-violent protest versus violent repression by state forces. Father Georgii Gapon • In December 1904, a strike occurred at the Putlilov plant in Saint Petersburg. Sympathy strikes in other parts of the city raised the number of strikers above 80,000. Father Georgii Gapon, a priest, organized a peaceful "workers' procession" to the Winter Palace to deliver a loyal petition to the Tsar on Sunday, January 22 1905). The petition asked for reforms such as an end to the Russo-Japanese war, expanded suffrage, an 8-hour work day, higher pay and the end to forced overtime in factories. The procession was well stewarded by followers of Gapon and any terrorists and hot-heads were removed and all the participants checked for weapons. Troops had been deployed around the Winter Palace and at other key points. • On 22 January, a Sunday, striking workers and their families gathered at six points in the city. Clutching religious icons and singing hymns and patriotic songs, they proceeded towards the Winter Palace without police interference. The demonstrators brought along their families in hope of arousing the Tsar's sympathy and the women and children were placed at the front of the demonstrations. However, the Tsar had left the city on January 8. Army pickets near the palace fired warning shots, and then fired directly into the crowds. Gapon was fired upon, and although around forty people surrounding him were killed, he was uninjured. Bloody Sunday – 22 January 1905 The number killed is uncertain. The Tsar's officials recorded 96 dead and 333 injured; anti-government sources claimed more than 4,000 dead; moderate estimates still average around 1,000 killed or wounded, both from shots and trampling. Resistance Strikes • Strikes had long been part of the workers’ repertoire of self-defence tools. In 1905, and especially in the intense aftermath of Bloody Sunday, use of this nonviolent tactic grew to an unprecedented level. Strikes took place all over the country protesting politics as well as economic grievances. • Small revolutions were taking place all over Russia. Universities closed down when the whole student body complained about the lack of civil liberties by staging a walkout. Lawyers, doctor, engineers, and other middle-class workers established the Union of Unions and demanded a constituent assembly. Leon Trotsky and other Mensheviks established the St. Petersburg Soviet. Shortly over 50 of these soviets were formed all over Russia, forming the new repositories of authority for the working class and as a result beginning to assume some government prerogatives. • With the establishment of the Moscow Soviet came the great October Strike. Industrial workers and railwaymen all over Russia went on strike – this paralyzed the whole Russian railway network and communication lines came to an abrupt halt in all the major cities of the Baltic region, leading to the “Days of Freedom” which ended in the failed, violent Moscow Uprising, an event which exemplified the new radical violent wing of the political opposition. Russian peasants in 1905 The revolution of 1905 marked a turning point in peasant life. Whatever remnants of the Tsar myth that survived among the peasants were smashed on Bloody Sunday when troops fired on a large crowd of unarmed workers. Even before 1905 peasant riots and estate burnings had grown dramatically. By the late summer of 1905 the countryside was in full scale revolt. Organized by intellectuals into a Peasant Union, peasants increasingly discovered how to express their demands.. In order to pacify the peasants the government moved to remove all remaining feudal restrictions on peasant and equality with other citizens. It followed up with a law permitting peasants to withdraw their land holdings from communal ownership and consolidate them under their own private ownership. Concession & Repression The October Manifesto The October Manifesto is “a whip wrapped in the parchment of a constitution” Trotsky • Sergei Witte, Chief Minister, advised Nicholas II to make concessions. He eventually agreed and published the October Manifesto. This granted freedom of conscience, speech, meeting and association. He also promised that in future people would not be imprisoned without trial. Finally he announced that no law would become operative without the approval of a new organization called the Duma. • With the Manifesto, the government did go a long way towards fulfilling the wishes of the opposition, as far as it could go without dissolving itself – if the terms of the agreement were kept. • By now the opposition was wary of false promises by the government, and wanted to continue its struggle, but the movement was coming to a natural halt. It could have declared victory, in fact; it had achieved some real change through noncooperation. Concession & Repression Dumas & Government “To the Emperor of all the Russians belongs the supreme autocratic and unlimited power. Not only fear, but also conscience commanded by God Himself, is the basis of obedience to this power” The Fundamental Laws of the Russian Empire • The first meeting of the Duma took place in April 1906. The composition of the Duma had been changed since the publication of the October Manifesto, and the tsar’s Fundamental Laws were in full effect. Tsar Nicholas II had also created a State Council, an upper chamber, of which he would nominate half its members. He retained for himself the right to declare war, to control the Orthodox Church and to dissolve the Duma. The Tsar also had the power to appoint and dismiss ministers. • At their first meeting, members of the Duma put forward a series of demands including the release of political prisoners, trade union rights and land reform. Nicholas II rejected all these proposals and dissolved the Duma. In April, 1906, Nicholas II forced Sergi Witte to resign and replaced him with the more conservative Peter Stolypin. Stolypin attempted to provide a balance between the introduction of much needed land reforms and the violent suppression of the radicals (execution for sedition - the hangman’s noose was referred to as “Stolypin’s Necktie”). The next Duma convened in February, 1907. This time it lasted three months before the Tsar closed it down. Legacy “Although with a few broken ribs, Tsarism had come out of the experience of 1905 alive and strong enough” Trotsky • The 1905 Revolution involved several forms of empire-wide resistance with no real single aim or cause. In the longer term, the revolution can be seen as the culmination of intense social unrest which stemmed from the Tsarist regime and the “backwardness” of the Russian state. • The autocratic government were able to crush the revolution using a combination of offering concessions and using repressive tactics, but the opposition could easily have been successful had it employed a more coherent nonviolent strategy. Due to the Tsarist regime’s employment of ruthless repressive tactics to ultimately crush any and all popular opposition, the 1905 Revolution has to a great extent only been remembered as a violent and bloody struggle, a “massacre of the innocents”. • It is possible to say, however, that there has been little correlation in movements since between the level of violence employed toward nonviolent protesters and their success, and the ultimate failure of nonviolence in 1905 to achieve its stated aims can be attributed to a variety of other factors. • Undoubtedly, a revolutionary mood permeated urban Russian society until this point as a result of government economic and political policies. Given such circumstances it seems unlikely that nonviolence would emerge as the chosen expression of social discontent, yet factors including a strong initial faith in the divine right Tsar and the vision of opposition leaders including Gapon made it so. • Had the government acknowledged the extensive grievances of the people in the pre-revolutionary period there would have been little cause for such widespread opposition to form at all and therefore no need to deploy such repressive tactics as those the autocratic regime resorted to at Bloody Sunday. This is not to imply that opposition to the Tsarist regime in 1905 steered entirely clear of violence and threats of such. Arguably violence breeds violence and it can be said that in response to government use of intensely violent repressive tactics to thwart earlier efforts the opposition thought perhaps fighting fire with fire would yield more satisfactory results. • • • For the most part, it is difficult to say that nonviolent tactics were chosen by the leaders and organised opposition of the 1905 Revolution for moral reasons, but rather as a pragmatic strategy. Nonviolent tactics were taken up by the masses in good faith, in support of their leaders’ vision, rather than as a result of any moral attachment and as such were in constant jeopardy of being abandoned for any other workable strategy if they were seen to be failing. Certainly, the revolution as a whole failed in the short term, yet retrospectively it is difficult to ignore its long term effects. Despite many of the concessions it granted being later taken away by the Tsar in a desperate effort not to concede any power to the people, the October Manifesto represented a definitive step toward reform. The Revolution of 1905, as Lenin contended, provided a model for February and October 1917 in that it demonstrated that something could be done to alter the nature of government, providing the impetus for further revolutionary action. It can also be considered an antecedent for later nonviolent movements in general as - despite the revolution as a whole being looked upon as unsuccessful - it demonstrated that rulers can only be genuinely powerful if the ruled give their consent through its effective use of strike action. • Ultimately, though it set a precedent for 1917 through very nearly bringing down the regime, the non-violent tactics did not work as far as achieving the goals the resistance desired. Among several reasons, this may have been due to: – The government’s smart move of making concessions when weak then snatching them away once it had recovered (in the October Manifest and then the Fundamental Laws). – The economic situation that triggered the whole revolution was getting better as 1906 approached, and troops returning home could restore order (at the end of the Russo-Japanese war). – The political demands thrown into the mix by the intelligentsia and small new class of proletarian workers were not the cause the less revolutionary-minded majority (the peasants) were protesting or cared much for, especially after their original leader, Gapon, left the scene. – There was no real cohesion between the different groups in the vast country, and thus little organisation, strategy etc. – The people recognised the government would simply continue to crush any opposition ruthlessly and quit before they ended up dying for the cause, especially when the movement turned violent around the time of the Moscow Uprising. “Russia lives under emergency legislation, and that means without any lawful guarantees… Autocracy is a superannuated form of government… That is why it is impossible to maintain this form of government except by violence” Tolstoy in “An Open Address to Nicholas II”