The third and final connection is what makes Manifest Destiny and

Adoration on Stage, Assimilation at

Home

Buffalo Bill’s show Indians, Reformers, and Manifest Destiny during the Late Nineteenth Century.

MA Thesis, American Studies Program, Utrecht University

By

Wouter de Jong

3475905

July 2, 2014

i

Content

Content

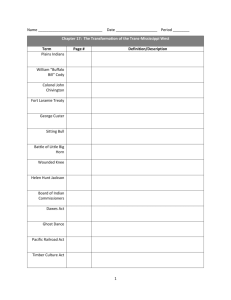

Chapter 3: Christian and Humanitarian Opposition; the Reformers ............................. 50

1

Preface

Preface

“Other nations have the avowed object of thwarting our policy and hampering our power, limiting our greatness and checking the fulfillment of our Manifest Destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” 1

John O. Sullivan, United Stated Democratic Review, July 1845

Introduction

On May 17, 1883, William Frederick Cody rode into an arena at the Omaha Fairgrounds to open

‘The Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition’, and by doing so started his career as

Buffalo Bill. For more than three decades, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show would venture across

America and Europe, providing its audience not only with entertainment, but with ideological images of American society. Between 1883 and 1907, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show expended in size, including ever more Native Americans, cowboys, prairie animals, and a wide variety of international performers, such as Mexican Gauchos. In 1893, the show performed for nine months outside the Columbian Expedition in Chicago, and for the first time included performers form other continents: military units from England and Germany, Cossacks from Eastern-Europe,

African tribesman, and many more. Although the show was still centered on iconic scenes depicting the American West, it now included aspects of frontier life from other continents, giving the show an international identity.

2

1 John O’Sullivan, “The Great Nation of Futurity.” United States Democratic Review 6 (1845): 426. Accessed

April 14, 2014. http://digital.library.cornell.edu/cgi/t/text/pageviewer-idx?c=usde;cc=usde;idno=usde0006-

4;node=usde0006-4%3A6;view=image;seq=350;size=100;page=root .

2 L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque; University of

New Mexico Press, 1996), 1-4.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

2

Preface

Show Indians

The hiring of Native Americans as performers, or ‘show Indians,’ for reenactments of the

American West was not a new phenomenon. During the 1870’s, Cody was involved in multiple stage productions, both as producer and performer, which made Cody inspired to provide his audiences with spectacular performances. He achieved this by including real horses to these stage productions, creating special effects to increase the realism of the performances, and make

Native Americans visible and recognizable for the audience. During the 1870’s, Native Americans were played by ‘supers,’ white performers dressed up as Native warriors, wielding bows and feathered war bonnets. However, during the late 1870’s, Cody began to aim for the most realistic representation of these Native warriors by hiring actual Native Americans to perform on stage.

These ‘Indian performers’ were not a new phenomenon to the entertainment business; they had involved in the business since the 1840’s, working for circuses and exhibitions as ‘exotic curiosities.’ Cody saw potential in Indian performers and began to include them in his theater productions by 1877.

3

Native performers were appealing for the audiences, who longed to see the representation of these “noble savages.” 4 Cody’s realization of their popularity did not take long; he recognized the vital role Native Americans could play in the reenactment of the American West and frontier life. This conclusion led Cody to aim for a type of performance much greater then a stage production; a Wild West show.

5

Reformers

However, the story of Native performers is not solely a serenade of success and adoration; there were skeptical eyes looking at them as well. These eyes belonged to a group of people critical to

3 Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage Books,

2005), 190-195.

4 Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America, 195.

5 Robert W. Rydell and Rob Kroes, Buffalo Bill in Bologna: the Americanization of the World, 1869-1922

(Chicago; Chicago University Press, 2005), 30.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

3

Preface the employment of Indian performers by Cody and were concerned about the consequences of being a performer on a Wild West show. Commonly referred to as ‘Reformers,’ these individuals

“alleged mistreatment and exploitation […] and became concerned about the show’s effects on assimilationist programs and on the image of the Indian in popular mind.” 6 Reformers were often involved with the Indian Rights Association (IRA), the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), or other humanitarian, mostly Christian, organizations. Their criticism was built on assumptions of exploitation and mistreatment, supported with a continuing attention for deadly accidents during the show, which included Native performers.

7

Assimilation policy

Yet, the main point of critique on the hiring of Indian performers was based on the presumed negative effects on the assimilation policy of the U.S. government. During the nineteenth century,

America witnessed a change in political ideals regarding race; while political rhetoric around the

1800’s was imbedded with an optimistic view on racial improvability, the 1850’s bookmarked political rhetoric built on assumptions of superiority of the Anglo-Saxon race and inferiority of other races. Partly responsible for this change in ideals was the continuing armed conflict with

Native American tribes. After these conflicts were ‘resolved,’ U.S. government started to focus on assimilating Native Americans, in order to make U.S. citizens out of them.

8

A small side note has to be made after the term ‘assimilation policy’ has been mentioned.

There was no single, clearly defined assimilation policy; this has become the overlapping term for scholars, used to refer to several legal, social, and cultural programs and policies of education and transforms, aimed at transforming several aspects of Native American life. These programs and

6 L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque; University of

New Mexico Press, 1996), 5.

7 Moses, Wild West Shows and Images of American Indians, 2-6.

8 David R. Wrone, "Indian Treaties and the Democratic Idea," Wisconsin Magazine of History 70 (1986): 83-

106.; Reginald Horsman, “Scientific Racism and the American Indian in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” The

Western Historical Quarterly 27 (1975): 153.; Anders Stephanson, Manifest Destiny: American Expansion

and the Empire of Right (New York; Hill and Wang, 1995), 24-26.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

4

Preface policies were issued and executed by the U.S. government and were aimed at assimilating Native

Americans, which resulted in the origination of the term ‘assimilation policy.’ This research will follow the example of scholars and use the term ‘assimilation policy’ when it is referring to the several actions and policies aimed at assimilating Native Americans.

The second half of the nineteenth century proved to be a complex and difficult phase for the assimilation policy. Obvious examples are horrific events such as the battle of Little Bighorn in

1872, the Ghost Dance uprising in 1889, and the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. Forced assimilation became a key policy in dealing with Native-American tribes in the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century. In this context, the critique of Reformers on the hiring of Indian performers is understandable; Native Americans were given an opportunity to reenact their own culture, an opportunity non-existent on reservations.

9

Manifest Destiny

In 1845, John O’Sullivan, a politician and editor of the Democratic Review, coined a term that would have a profound impact on American ideas about race, gender, and empire. According to

O’Sullivan, it was America’s mission “to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions." 10 Manifest Destiny provided American society with a collection of ideals on how America should exists and why. It influenced the continuing search for an ‘American identity’ and proved valuable to U.S. governmental policies, both foreign and domestic.

11

Considering this context, it is possible to recognize several connections between the

Native-American assimilation policy and the ideals expressed by Manifest Destiny. If it was

9 Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage Books,

2005), 369-375.; Anders Stephenson, Manifest Destiny: American Expansion and the Empire of Right (New

York; Hill and Wang, 1995), 24-26.

10 Robert J. Scholnick, “Extermination and Democracy: O'Sullivan, the Democratic Review, and Empire,

1837—1840.” American Periodicals 15 (2005): 124.

11 Stephanson, Manifest Destiny, 1-6.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

5

Preface

America’s mission develop, civilize, and cultivate the continent, it is not difficult to identify a base for conflict between U.S. government and Native Americans; the first desired land, which was occupied by the latter. The logical result of this problem was the start of relocation of Native tribes, one of the first stages of Native-American policy, followed by the above mentioned assimilation policy. If the ideals promoted by Manifest Destiny were of significant influence on the creation of this assimilation policy, it is reasonable to assume these ideals can be identified in the debate surrounding Indian performers. Yet, contemporary scholars involved with the research on this debate seldom reflect on this connection. I believe there is such a connection.

Which ideological elements of manifest destiny regarding race and civilization can be identified as fundamental to the debate surrounding Native Americans performing in Cody’s Wild

West show during the late nineteenth century? This will be the central research question of my thesis. As mentioned earlier, this debate was dominated by Reformers; individuals usually affiliated with governmental organizations, such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs or private organizations, such as the Indian Rights Association, who labeled the employment of Native

Americans as exploitation and harmful to the Natives. However, several authors, such as Warren and Moses, define the ‘humanitarian’ arguments against Native employment as a façade for the actual fears of Reformers; the negative effects the employment would have on the governmental assimilation policy. However, Moses and Warren make no comparison between these Reformers and their arguments and the concept of manifest destiny. I believe there is such a connection, based in the ideals of manifest destiny and the ideals of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show.

This question interests me for several reasons. The two major topics, Buffalo Bill’s

Wild West show and manifest destiny, covered by this paper are intriguing subjects for research on themselves. The Wild West show was an important form of mass culture in the nineteenth century, as well as an important medium in the process of ‘Americanization.’ Especially the

European tour of Cody’s show was a catalyst for the spreading of American ideals on race,

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

6

Preface domesticity, gender, and imperialism. It had a similar function in the United States. Audiences were not only amused with a slightly fictional yet spectacular reenactment of life in the American

West, but with messages on racial order, domestic ideals, gender relations, and civilization ideals.

12

Status Quaestionis

Manifest Destiny and Buffalo Bill both have been significant topics of research and debate during the second half of the nineteenth century. Manifest Destiny is most often analyzed in a context of territorial expansion; the end of the nineteenth century signaled an expansion of American territorial influence across the globe, the Philippines, Cuba, and Mexico being the prime examples of this new ‘imperial’ America. This imperial belief can be traced back to the providential mission bestowed upon the United States to spread Anglo-Saxon civilization across the continent and the globe as a guiding light for others to follow. Over the last three decades, this connection between

Manifest Destiny and American imperialism has become a significant source for debate and research and the topic of several important books. Primary examples of such books are Anders

Stephanson’s Manifest Destiny: American Expansion and the Empire of Right and Amy S.

Greenberg’s Manifest Destiny and American Territorial Expansion: A Brief History with Documents.

Greenberg’s book provides an example of a change in research interests regarding

Manifest Destiny; primary sources. Manifest Destiny is not a clearly defined concept, but rather an idea of ideal interpretable in multiple ways, depending on which context is provided. Whereas

Stephanson and Greenberg focus on the territorial expansion aspect, scholars during the 1960’s and 70’s focused on the racial component of Manifest Destiny, thereby transforming the term into an explanation for certain social conflicts based on race and gender. The best example of

12 Robert W. Rydell and Rob Kroes, Buffalo Bill in Bologna: the Americanization of the World, 1869-1922

Chicago; Chicago University Press, 2005), 12-13, 31-33.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

7

Preface such a work is Reginald Horsman’s Race and Manifest Destiny: the Origins of American Racial

Anglo-Saxonism.

William “Buffalo Bill” F. Cody is most commonly identified with the concept of

Americanization and popular culture through his most recognizable achievement; the famous

Wild West show. Cody as a person is a complex topic of research, since it is difficult to objectively divide William F. Cody form his alter-ego, Buffalo Bill. Notable Buffalo Bill scholars, like Louis S.

Warren and Don Russell, have stressed the importance of keeping the two personalities apart in their respective works. Especially when the topic of research is Cody’s Wild West enterprise, it can be quite difficult to keep fact and fiction apart.

The twentieth century has seen a steady production of academic works concerning Cody’s show and the significance of the show on Americanization and popular culture. Several books have been of significant influence on this field of research: Louis S. Warren’s Buffalo Bill’s

America: William Cody and the Wild West Show, Robert W. Rydell’s and Rob Kroes’ Buffalo Bill in

Bologna: the Americanization of the World, 1869-1922, Don Russell’s The Lives and Legends of

Buffalo Bill, and Paul Redding’s Wild West Shows. Most of these academic publications on Cody’s show and its influences come from the second half of the twentieth century and tend to focus on the implications of the show on American and European society and the social and ideological values represented in the show. Although the connection between Manifest Destiny and the show is scarcely uttered in these exact words, there has been research on the connection between the racial and imperial ideals expressed by Manifest Destiny and the content of Cody’s show. The primary example of such research is Robert W. Rydell’s and Rob Kroes’ Buffalo Bill in

Bologna: the Americanization of the World, 1869-1922.

Native American studies has become an academic field on its own during the last two decades of the twentieth century, containing a steady supply of material based on Native

American culture. However, material related to political issues surrounding Native Americans and

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

8

Preface their place in American society throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century can often be located in the field of American Studies. Especially the topic of relocation and assimilation policy has become an important part of American Studies over the last five decades. An important figure in this field of research is Franchis Paul Prucha, author of American Indian Policy in Crisis: Christian

Reformers and the Indian, Documents of the United States Indian Policy, and The Great Father:

The United States Government and the American Indians. Prucha’s work has been of significant influence on the process of explaining the governmental Native American policy throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century by locating important primary sources and identifying aspects of Native American policies similar to social ideal in American society.

Contemporary American Studies contains a significant amount of research and material on Manifest Destiny, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show, and the Native American assimilation policy.

These subjects share a similarity; scholars have been occupied with connecting these subjects with ideals of American culture and society. This paper will follow a similar direction in trying to establish a connection between fundamental ideals expressed by Manifest Destiny, the Native

American performance elements of Cody’s Wild West show, and the opposition of Reformers to these show elements. This connection can be labeled as a political debate surrounding the participation of Native performers in Cody show. This debate included Reformers, William F.

Cody, and the arguments of both parties, which were based on the participation of Native

Americans in the show and the role they played.

Within the academic debate, there has been attention for the connection between ideals on civilization and race and the discussion surrounding show Indian, yet a specific comparison between this discussion and Manifest Destiny has not been established. I hope to support this connection with this research. After doing the research for this proposal, I identify myself with the opinion of Warren, Moses, Kroes, and Rydell; the employment of Native Americans by Buffalo

Bill’s show was not an act of exploitation or suppression, but an act of opportunity, both

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

9

Preface economic and cultural. Essentially, by reenacting their own history and culture, Indian performers established a process of preservation of their history and culture. Besides that, they were employees by definition; they received an opportunity to make a decent living for themselves, an opportunity basically non-existent on the reservations, where job opportunities were provided by the U.S. government. These opportunities were not very lucrative, which is why performing in

Wild West shows became an attractive alternative for live on the reservations.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

10

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age

“In the Eastern States, or even east of the Mississippi, the methods of these people [frontier men] are comparatively unknown, and it is for the purpose of introducing them to the public that this little pamphlet has been prepared. Hon. William F. Cody ("Buffalo Bill"), in conjunction with Mr.

Nate Salsbury, the eminent American actor (a ranch owner), has organized a large combination that, in its several aspects, will illustrate life as it is witnessed on the plains; the Indian encampment; the cowboys and vaqueros; the herds of buffalo and elk; the lassoing of animals; the manner of robbing mail coaches; feats of agility, horsemanship, marksmanship, archery, and the kindred scenes and events that are characteristic of the border. The most completely appointed delegation of frontiersmen and Indians that ever visited the East will take part in the entertainment, together with a large number of animals; and the performance, while in no wise partaking of the nature of a "circus," will be at once new, startling, and instructive.” 13

John M. Burke, General Manager. May 1, 1883. Omaha, Nebraska.

Introduction

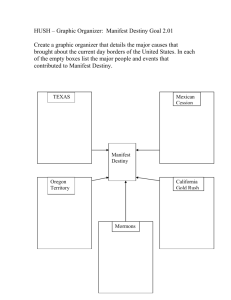

During the second half of the nineteenth century, Manifest Destiny became a term of explanation for the staggering development of the United States. The ideal of a providential mission to spread civilization across the continent had materialized in an expanding territory, a fast growing population, and steady economic development. Especially the expansion of the U.S. economy had become an important goal for U.S. government at the beginning of the nineteenth century and replaced the urge for territorial expansion. An important reason for this was the ‘problem’ that arose with the annexation of land containing ‘nonwhite peoples,’ like Mexicans and Native

Americans. The question on what to do with these specific groups divided U.S. politicians and proved to be a tough issue to resolve. As a result, the economic expansion of the United States became more important than territorial expansion, thereby avoiding the ‘problem’ of nonwhite people.

14

13 “Program Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Congress of Rough Riders of the Worlds, 1893,” Folder 25, Box

13, Cody, William Frederick/Buffalo Bill Collection (WH72), Denver Public Library, Denver, Colorado.

Hereafter referred to as Cody Collection Denver.

14 Thomas Jefferson, “Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1805,” in Manifest Destiny and American

Territorial Expansion: A Brief History with Documents, ed. Amy S. Greenberg (New York, Bedford/St.

Martins, 2012), 55-57.; Daniel Webster, “Letter to the Citizens of Worcester Country, Massachusetts,” in

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

11

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age

In this era of changing politics and ideals, a man arose with the dream of educating

American citizens on his own ideal. This man was William F. Cody, better known as Buffalo Bill, and his ideal was the American West. Cody, a man well familiar with life at the Western frontier, saw the world he came to know and love coming to an end, an assumption which triggered him in pursuing a career as entertainer and educator. The result of this pursuit was the Buffalo Bill Wild

West show, a staggering entertainment enterprise that would tour the American continent as well as Europe, baffling millions of people with stunning representations of the American frontier live, including the mysterious ‘red savages,’ or Native Americans. The quote above, taken from an

1893 show program, gives a good impression of what Cody had in store for his audience.

Manifest Destiny and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show are both important aspects of a turbulent era at the end of the nineteenth century. Considering this fact, it seems reasonable to assume a possible connection can be made between the two. As mentioned in the introduction, this research is aimed at finding a connection between the ideals of Manifest Destiny and the political discussion dominated by Indian Reformers. This task will prove impossible if there is no context in which to place the main question. Therefore it is essential to establish and clarify a connection between Manifest Destiny and Buffalo Bill and his Wild West enterprise, in order to provide this research with a solid contextual foundation, before it ventures into its central timeframe of 1889-1893. This chapter will provide such a foundation. It will identify central aspects of Manifest Destiny and Cody’s Wild West show and compare these elements in order to clarify the connection between them. This chapter will be guided by the following central question: which central elements of Manifest Destiny were represented in Cody’s show?

The question above has both a descriptive and argumentative element. The descriptive element is built on the contextual foundation being provided in this chapter by locating central

Manifest Destiny and American Territorial Expansion: A Brief History with Documents, ed. Amy S. Greenberg

(New York, Bedford/St. Martins, 2012); 90-92.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

12

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age elements. The argumentative element of this chapter is based on the fact that it will establish a connection between central elements of Cody’s show and Manifest Destiny. Since Manifest

Destiny did not have a clearly established definition, its central aspects are open to debate. The same can be said about elements from Cody’s show, which has elements that can be interpreted in several ways, as is proven by the debate surrounding Native performers. This chapter will thus be both a descriptive and argumentative chapter, aimed at providing this research with necessary context.

Origins of Destiny and Territorial Expansion

Although the term Manifest Destiny was coined in 1845, the idea of ‘American exceptionalism’ lies at the foundation of the United States. Upon arrival at the new continent, the first Puritan settlers envisioned their journey as blessed by God. As William Bradford describes it in his 1650 manifest Of Plymoth Plantations, the new settlers had to depend on this blessing, “for what could now sustain them but the spirit of God and his Grace?” 15 Indeed, the first wave of settlers arrived at a continent not yet touched by western civilization, so the fact that it was their ‘mission’ to change this was unmistakably connected to an assumption of a divine blessing. A well-known concept representing this assumption is the ideal of “a city upon a hill. The eies of all people are uppon us.” 16 From the very beginning, these two ideals were fundamental to the settlement of the American continent, so two of the core issues of the 1845 definition of Manifest Destiny, providential mission to spread civilization, as an example for all of humanity, are much older than

O’Sullivans’ definition.

17

15 William Bradford, “On Plimoth Plantation,” in Manifest Destiny and American Territorial Expansion: A

Brief History with Documents, ed. Amy S. Greenberg (New York, Bedford/St. Martins, 2012), 41-41.; John

Wintrop, “A Model of Christian Charity,” in Manifest Destiny and American Territorial Expansion: A Brief

History with Documents, ed. Amy S. Greenberg (New York, Bedford/St. Martins, 2012), 43-44.

16 Wintrop, “A Model of Christian Charity,” 43-44.

17 Amy S. Greenberg, ed., Manifest Destiny and the American Territorial Expansion: a Brief History with

Documents (New York, Bedford/St. Martins, 2012), 4-5.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

13

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age

Although the ideals described above were fundamental to the origin of the United States, they were not solely responsible for territorial expansion during the early Republic period of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. The primary reasons for territorial expansion were a fast growing population and security concerns. According to the United States Census Bureau, the

American population nearly tripled over the turn of the eighteenth century, expending from

3.929.214 registered citizens in 1790 to 12.860.702 registered citizen in 1830.

18 The primary stimulators behind this exponential growth were a low mortality rates and an increasing stream of immigrants from Europe. An inevitable result of this growing population was a constant need for new land to support a growing rural population, which took great pride in private ownership of land and did not hesitate to venture into unknown territories to the West, with or without governmental permission.

19

Native lands

By the end of the 1830’s the United States covered almost half of the American continent. The western border was set along the contemporary states of Louisiana, Missouri, Illinois, and

Michigan. The northeast territory of the continent known as the Oregon territory, which consisted of modern-day Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, existed under a combined British-U.S. occupation, while a large part of the contemporary Midwest fell under the unorganized Missouri territory.

20

During the period of territorial expansion described above, conflicts with Native

Americans emerged. There is a simple cause for these conflicts; Native Americans occupied land that was desired by the United States, which led to increasing efforts of U.S. government to ‘buy’

18 “American Census Bureau, 1830 facts,” last modified April 16, 2014, https://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/fast_facts/1830_fast_facts.html.

19 Harriet Martineau, Society in America: volume II (New York; Unders and Otley, 1837), accessed on April

22, 2014, http://books.google.nl/books/about/Society_in_America.html?id=AfT2MxEbcjQC&redir_esc=y ,

291-293.

20 “American Census Bureau, 1830 Map,” last modified April 16, 20014, http://www.uscensus.org/states/map.htm#1830 .

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

14

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age the Indian lands by way of treaties. Not every acre of land that came into U.S. possession was obtained fairly; so called squatters – white settler who occupied land outside the U.S. border, proved to be an everlasting problem. By ignoring federal or state policies against illegal settling of

Indian lands, squatters formed a real threat to diplomatic treaties, established between U.S. government and Native tribes during the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. 21

Despite the problems created by the actions of squatters, federal government had no intentions of putting a stop to the illegal occupation of land. Two documents can provide more insight to this complex situation. On December 6, 1830, President Andrew Jackson held his State of the Union Address, in which he reflected on the federal Indian policy and proposed a future way of resolving territorial conflicts with Native-American tribes;

“It gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy of the

Government, steadily pursued for nearly 30 years, in relation to the removal of the

Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation. Two important tribes have accepted the provision made for their removal at the last session of

Congress, and it is believed that their example will induce the remaining tribes also to seek the same obvious advantages. The consequences of a speedy removal will be important to the United States, to individual States, and to the Indians themselves. The pecuniary advantages which it promises to the Government are the least of its recommendations. It puts an end to all possible danger of collision between the authorities of the General and State Governments on account of the Indians. It will place a dense and civilized population in large tracts of country now occupied by a few savage hunters.” 22

The passage above can provide multiple insights. First, the acquiring of new land was a central goal for U.S. government, which can be connected to the agricultural character of

American society; more people required more food, which required more cultivatable land.

Second, the statement made by Jackson about ‘savage hunters’ suggests a negative racial attitude of U.S. government towards Native Americans. This connection will be analyzed in greater detail in the next paragraph. And third, a ‘solution’ for the problem of squatters on Native lands would

21 Amy S. Greenberg, ed., Manifest Destiny and the American Territorial Expansion: a Brief History with

Documents (New York, Bedford/St. Martins, 2012), 10-13.

22 “Andrew Jackson, “State of the Union Address, 1830,” accessed April 20, 2013. www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=8032 .

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

15

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age be the annexation of these lands and the removal of Native-American tribes, which can hardly be considered an actual solution. This policy towards Native Americans and their claims to land were characteristic for Jackson’s presidency. In 1830, he passed the Indian Removal Act, a legislative piece aimed at relocating Native-American tribes from the land they claimed to poses. What followed was an aggressive policy of removal, often not in line with earlier established treaties, laws, and Supreme Court rulings.

23

An example of such an aggressive and partial illegitimate act of removal is the Cherokee

Nation removal in 1838 and 1839. The Cherokee did not respond with force, but tried to play the diplomatic game they were taught by U.S. government through the negotiation of various treaties in the first three decades of the nineteenth century. Between the signing of a relocation treaty between U.S. government and a small segment of the Cherokee nation in 1835 and the actual removal in 1838, representatives of the Cherokee nation addressed Congress on multiple occasions in an effort to protect their land. The following passage is taken from such an address, filed in 1836;

“It would be useless to recapitulate the numerous provisions for the security and protection of the rights of the Cherokees, to be found in the various treaties between their nations and the United States. The Cherokees were happy and prosperous under a scrupulous observance of treaty stipulations by the government of the United States, and from the fostering hand extended over them, they made rapid advances in civilization, morals, and in the arts and sciences. Little did they anticipate, that when taught to think and feel as the American citizen, and to have with him a common interest, they were to be despoiled by their guardian, to become strangers and wanderers in the land of their fathers, forced to return to the savage life, and to seek a new home in the wilds of the far west, and that without their consent.” 24

23

Anders Stephanson, Manifest Destiny: American Expansion and the Empire of Right (New York; Hill and

Wang, 1995), 24-25.

24 “Memorial and protest of the Cherokee Nation, June 22, 1836,” in Manifest Destiny and American

Territorial Expansion: A Brief History with Documents, ed. Amy S. Greenberg (New York, Bedford/St.

Martins, 2012), 67-68.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

16

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age

The passage above supports the claims made earlier in this chapter; treaty or no treaty, legal or illegal, the U.S. government was aiming for the annexation of Native lands. During the presidency of Andrew Jackson, treaties and legal support for land annexation became trivial to the hunger for new territory. However, the emergence of this policy of aggressive expansionism went hand in hand with a growing amount of critical voices. These critical voices came from the losing side of the battle for territory; European nations, most significantly the British and the

Spanish, and of course the various Native-American tribes who were victimized by the relocation policy. The most significant critics within American society were members of the Whig Party, the political opponent of Jackson’s Democratic Party.

25

It would be incorrect to describe the Whigs as critics of America expansion completely; they promoted the growth of the United States, but believed this should be achieved by optimizing the manufacturing sector and resource extraction within the existing borders and not by expending U.S. territory. According to the Whigs, a larger territory would be difficult to manage efficiently and would weaken the position of strength of New England, the Whigs’ seat of power. The rise of critical voices towards U.S. removal policies created problems for those who supported the policies. What was needed was a reasonable theory supporting the ‘right’ U.S. government had to claim Native lands. Manifest Destiny proved to be the solution.

26

Scientific racism

Although Manifest Destiny was coined in 1845, the message regarding providential expansion and civilization it expressed were widely recognized and supported in American society during the first half of the nineteenth century and coincided with a change in political rhetoric that took place around the 1840’s. American Studies scholar Reginald Horsmen describes this change in his 1975

25 Anders Stephanson, Manifest Destiny: American Expansion and the Empire of Right (New York; Hill and

Wang, 1995), 30-31.;

26 Stephanson, Manifest Destiny, 29-31.; Daniel Webster, “Letter to the Citizens of Worcester Country,

Massachusetts,” in Manifest Destiny and American Territorial Expansion: A Brief History with Documents, ed. Amy S. Greenberg (New York, Bedford/St. Martins, 2012); 90-92.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

17

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age essay Scientific Racism and the American Indian in the Nineteenth Century. In mid-nineteenth century, the general opinion of American society was one of white superiority and non-white inferiority, where the beginning of the nineteenth century was characterized by an opinion of racial improvability and opportunism for human civilization. This opportunistic view on race and society changed after Andrew Jackson’s presidency and resulted in an increasingly aggressive policy of expansionism and Indian relocation. The result was an American society supportive of the ideals on Anglo-Saxon superiority, which enabled the creation of something called scientific racism. This idea provided U.S. government with the argument they needed for their aggressive relocation policies; it was their natural right to claim land from the inferior ‘savages,’ since it was

America’s providential mission to spread civilization across the continent.

27

During the second half of the nineteenth century, Manifest Destiny and scientific racism came together in American society. The idea of a providential mission to spread civilization was still widely supported, but ideals on racial superiority and inferiority now accompanied this idea.

Manifest Destiny became an argument for the relocation of Native-American tribes, which were not white and therefore had no right to claim the land they had lived on for thousands of years.

Again, Andrew Jackson provides the words to capture this mid-nineteenth century ideal;

“Philanthropy could not wish to see this continent restored to the condition in which it was found by our forefathers. What good man would prefer a country covered with forests and ranged by a few thousand savages to our extensive Republic, studded with cities, towns, and prosperous farms, embellished with all the improvements which art can devise or industry execute, occupied by more than 12,000,000 happy people, and filled with all the blessings of liberty, civilization, and religion?” 28

27 Reginald Horsman, “Scientific Racism and the American Indian in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” The

Western Historical Quarterly 27 (1975): 152-153.

28 “Andrew Jackson, “State of the Union Address, 1830,” accessed April 20, 2013. www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=8032 .

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

18

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age

After the Civil War, Manifest Destiny became a term connected to both the superiority of

Anglo-Saxon civilization and the Anglo-Saxon race. The term still supported the belief of

Americans in a providential mission of civilization, but now included an element of racial inferiority, which resulted in a stronger belief in the ‘right’ of the United States to occupy land, relocate Native American tribes, and force Anglo-Saxon civilization upon them. Manifest Destiny had become the main argument in favor of territorial expansion. There were several reasons for this continued craving for territory; internal problems regarding race, class, and gender divided the country. In order to secure the survival of the Anglo-Saxon race, the United States had to maintain a dominant position, both on and off the continent. The result of this attitude was the effort to civilize and relocate Native Americans, either with or without force.

29

Buffalo Bill emerges

On May 17, 1883, William Frederick Cody rode into an arena at the Omaha Fairgrounds to open

‘The Wild West, Rocky Mountain and Prairie Exhibition’, and by doing so started his career as

Buffalo Bill. For more than three decades, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show would venture across

America and Europe, providing its audience not only with entertainment, but with ideological images of American society as well. Between 1883 and 1907, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show expended in size, including more Native Americans, cowboys, prairie animals, and a wide variety of international performers, such as Mexican Gauchos. In 1893, the show performed for nine months outside the Columbian Expedition in Chicago, and for the first time included performers form other continents: military units from England and Germany, Cossacks from Eastern-Europe,

African tribesman, and many more. Although the show was still centered on iconic scenes

29 Amy S. Greenberg, ed., Manifest Destiny and the American Territorial Expansion: a Brief History with

Documents (New York, Bedford/St. Martins, 2012), 30-33.; Reginald Horsman, “Scientific Racism and the

American Indian in the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” The Western Historical Quarterly 27 (1975): 154-157, 167-

168.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

19

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age depicting the American West, it now included aspects of frontier life from other continents, giving the show an international identity.

30

It is essential to point out the complex relationship between William F. Cody and his alter ego Buffalo Bill. Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, many scholars have devoted their time to unravelling the intriguing life of Cody and Bill. One of these scholars is Louis

S. Warren, the author of Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show. This book provides its readers with an extensive insight in the life and career of Cody by shifting myth from reality and William Cody from Buffalo Bill. In order to maintain oversight of his research, Warren builds on a central thesis: How did Cody adapt his life experienced to be representable in his show? This question can be used for the sake of this research as well. Which social ideals were central to Cody’s life, and how did these ideals influenced the contents of his Wild West show?

31

Indian fighter

Before 1872, Cody made a living by scouting for the U.S. army and guiding hunting expeditions for officers and tourists. This period in Cody’s life would be a source for many historical deeds, both real and fictional, on which nineteenth century critics and twentieth century historians would ponder. A combination of mythical and actual events earned Cody the nickname ‘Buffalo Bill,’ a name that would stick to his persona till far after his death. Cody used his nickname to start a career in show business, after he discovered the popularity of Buffalo Bill as a frontier character.

During his career in show business, Cody introduced a wide variety of ‘personal experiences’ to his performances, many of which are doubted to be real. A telling example is Cody is his involvement in the battle at Little Bighorn, which would become a centerpiece of the show during

30 L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque; University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 1-4.

31 Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage Books,

2005), XIV-XV.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

20

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age the 1890’s. In this performance, Cody arrives just too late to save Custer’s life, while in reality,

Cody was not even near Little Bighorn when Custer made his final stand.

32

A second example of a myth represented as reality in Cody’s show is the famous scene

‘The scalping of Yellow Hand.’ The story told on stage was one of heroism, performed by Cody and a regiment of soldiers from the Fifth Cavalry in a skirmish with 200 Cheyenne warriors. According to the tales, Cody fought with Yellow Hand, a Cheyenne chief, and scalped him while shouting

“The first scalp for Custer!” 33 This scene was first performed on stage in 1879 and continued to be part of Cody’s productions for some years. An intriguing fact of this story is the high possibility of it being true. What makes this story interesting for this research is not its truthfulness, but the way it represented Cody as an ‘Indian fighter.’ 34

The image of Cody as an Indian fighter was central to his career as performer and show producer. It fitted the overall picture of Cody as a ‘true western frontier man,’ skilled in scouting, hunting, and above all, fighting Indians. This created the illusion that Cody was connected to

Native Americans at some level, which resulted in Cody’s nickname ‘white Indian,’ a man who incorporated Native-American fighting skills and social practices with a strong belief in American ideals regarding society, civilization, and race. This was not unusual for U.S. army scouts; in order to be successful at their job, scouts had to know Native lands and its occupants and Cody was no exception to this necessity. During a later stage in his career, Cody’s supposed connection to

Native Americans would become an important tool for the hiring of Native Americans to his show.

However, the fact is that Cody knew few Native Americans in person; the real connections Cody

32 Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage Books,

2005), 117-120.

33 “Program The Wild West: Buffalo Bill’s Rocky Mountain and Prairie exhibition, 1885,” folder 19, Box2,

Cody Collection Denver.

34 Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America, 120.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

21

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age had acquired were with middlemen who knew Native Americans, predominantly men already established in show business.

35

Cody’s America

The connection between Cody and Native Americans will be analyzed in greater detail further on in this research. What is of interest for this particular chapter, is the other side of Cody’s personality as frontier man and Indian friend; his perception of American society, civilization, and race.

It is important to recognize the complexity of the era in which Cody lived. As mentioned earlier, a collective ideal of Anglo-Saxon superiority rooted itself in American society after the

1850’s. This process also influenced the U.S. army and frontier life. In the popular mind, the army existed of Anglo-Saxon males, but the reality was quite different; over 50 percent of the soldiers in the U.S. army were foreign born and came from the ever growing stream of immigrants.

Although these foreign born soldiers possessed a white skin color, they were not considered

‘white.’ The term ‘white’ was applied to white, Anglo-Saxon men, born on American soil, who were Protestant and English speaking. The traditional example of this paradox is the Jewish immigrant; white of color but non-white in society. This complex definition of ‘white’ created tensions among soldiers and between them and their commanders.

36

Cody was no stranger to this racial tension. In his autobiography Life of Buffalo Bill, Cody makes several remarks regarding his position on race by ridiculing certain aspects of black and immigrant soldiers, like their speech. A telling example of this tendency is a passage in which Cody repeats a Black soldier, who wanted to “sweep de red debels from off de face ob de earth.” 37 This passage provides some insights in Cody’s opinion on a multiracial army. Within this melting pot of nationalities and cultures, Cody was a ‘true’ Anglo-Saxon male, which explains his popularity with

35 Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage Books,

2005), 120.

36 Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America, 97-99.

37 William F. Cody, Buffalo Bill’s Life Story: an Autobiography (New York; Skyhorse Publishing, 2010), 158.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

22

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age the army commanders, who were also Anglo-Saxon males. Despite his experience in a multiracial frontier army, the soldiers in Cody’s Wild West show were all white. There is a complex explanation for this turn of events, based on racial ideals, social tensions, and Manifest Destiny.

38

Manifest Destiny had already become affiliated with the ideals of Anglo-Saxon supremacy before Cody presented his all-white army to his audiences, so there is no need to describe this connection again. It is important, however, to apply to this connection some of the social issues that divided American society during the second half of the nineteenth century. One of these social issues was the growing consciousness of something called neurasthenia, a term invented by physician George M. Beard. According to Beard, American society grew anxious about the survival of the Anglo-Saxon race. The term was invented in 1880 and gathered support during the next two decades. When one combines this with the growing aggression towards European immigrants, the tensions in a multiracial army, and an economic depression taking flight in the late 1880’s, it is not difficult to understand the growing belief in Anglo-Saxon superiority and the revitalized support for Manifest Destiny’s core belief; Anglo-Saxon civilization would become dominant, simply because it was Anglo-Saxon civilization. But in 1890, a problem occurred; the

Western frontier was closed, putting a stop to the spread of Anglo-Saxon civilization. What was left behind was an anxious feeling of an uncertain future.

39

Representation of Civilization

It is during this period, troubled by social unrest, radical racial ideals, and a growing belief in

Manifest Destiny, that Cody exchanged the prairies for a career on stage. During the first three years if the 1880’s, Cody was faced with a challenge; recreating the violent frontier world suited for middle-class men, women, and children. Quite surprisingly, Cody succeeded not only in providing entertainments suitable for women and children but also in entertaining audiences

38 Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage Books,

2005), 99-101.

39 George Beard, “Neurastenia, or Nervous Exhaustion.” The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (1869):

217-221.; Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America, 94-103, 213-218.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

23

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age located at both sides of the political divide. During the twentieth century, many scholars have pondered on the following question; how did Cody succeed? The answers provided includes a wide variety of central aspects; racial messages, accuracy in representing the western frontier, promotion of Anglo-Saxon civilization, and the representation of a fundamental idea of domesticity in American culture. Indeed, all of these aspects have made an impact on the popularity of the show, but where can they be placed in a turbulent period in American society, imbedded with a strong belief in Manifest Destiny?

“And now, four centuries from the discovery of America, at the end of a hundred years of life under the Constitution, the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of

American history.” 40 These words lie at the center of one the most important publications in

American western history; Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis. The frontier, Turner argued, had come to an end in the 1890’s. U.S. government agreed with him; in 1890 the U.S. Census

Bureau concluded there was no more Western frontier.

41

This turn of events had some unforeseen consequences for American social ideas. In the mind of many Americans, the western frontier was the last place in which ‘true American values’ were still alive; white supremacy, manliness, and individualism. When the frontier closed,

American society became afraid for the existence of the American values, which resulted in a growing belief in neurasthenia. The western frontier became a memory in American society, one that reminded them of social problems in an urbanizing country and made them fearful for the existence of the Anglo-Saxon race.

42

When one considers the complex social situation described above, it is understandable why a wide variety of nineteenth century Americans and twentieth century scholars have

40 Frederick Jackson Tuner, The Frontier in American History (New York; Henry Holt & Co., 1920), accessed

23 April, 2014, http://xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/turner/.

41 Robert Porter, Henry Gannet, and William Hunt, eds., Report on Population of the United States at the

Eleventh Census: 1890, Part I (Washington D.C.; Government Printing Office, 1895) XXXVIII-XXXIV, accessed

April 23, 2014, http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/1890a_v1-01.pdf

42 Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage Books,

2005), 213-217.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

24

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age concluded that it was the aspects of white, racial superiority and the representation of Anglo-

Saxon civilization what made Cody’s show a success. Although these individuals were nog entirely wrong, this image is too simplistic to be used as an explanation for the show’s popularity with the

American audience. Cody’s wish to attract middle-class families could not be realized by actual reenactments of the western frontier; bloody battles between soldiers and Native Americans could be considered as a boost for racial ideals on Anglo-Saxon superiority, but it would not appeal to Cody’s preferred audience. The key to Cody’s success can be found in what Louis C.

Warren labels as the “domesticating of the Wild West.” 43 This process was based on the inclusion of subtle racial and civilization ideals, a significant dose of reality, and a central figure to keep control over the show and its acts.

44

Domestication and artful deception

The first Wild West show produced by Cody consisted of three categories of events; races, reenactments, and shooting exhibitions. These three categories would be the backbone of Cody’s show as it transformed from dress rehearsal in 1883 to mass entertainment spectacle in 1893.

Proof of this can be found in several show programs that remain today, like the program of the

October 1883 show in Chicago’s driving park and the program of the 1893 show outside the

Chicago world fair.

45

The 1883 show opened with a bareback pony race, followed by a reenactment of the Pony

Express. Both were performed by Pawnee Indians and cowboys, as was the Attack on the

Deadwood Mail Coach that followed. After these ‘historic’ reenactments the audience was dazzled by multiple sharpshooting exhibitions, performed by Cody himself, the notorious A.H.

43 Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage Books,

2005), 211.

44 Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America, 218-229.; Robert W. Rydell and Rob Kroes, Buffalo Bill in Bologna: the

Americanization of the World, 1869-1922 (Chicago; Chicago University Press, 2005), 29-34.

45 “Program The Wild West: Buffalo Bill’s Rocky Mountain and Prairie exhibition, 1885,” folder 19, Box2,

Cody Collection Denver.; “Program Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Congress of Rough Riders of the Worlds,

1893,” Folder 25, Box 13, Cody Collection Denver.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

25

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age

Bogardus, and several cowboys shooting from horseback. The show concluded with Cowboy Fun, a demonstration of horsemanship performed by skilled, white, rodeo performers.

46

The 1893 program shows many similarities with the 1883 show. The Pony Express, the

Deadwood Mail Coach, the sharpshooting exhibitions, and several acts of extraordinary horsemanship were still central to the show. The main difference between the two shows is its size; the 1893 show included more cowboys, both from the United States and Mexico, a wide variety of Native Americans from different tribes, international soldiers from Europe Germany and the Middle-East, and several other stars, like Miss Annie Oakley, a skilled female sharpshooter.

However, the show was still structured around races, historic reenactments, and sharpshooting exhibitions.

47

These three central elements provide the key to understanding how Cody reached the audience wished for. The show was not focused on the defeat of Native Americans, thereby promoting Anglo-Saxon supremacy over an inferior race, realistic reenactments of bloody warfare, or on purely entertaining acts, such as the horse- and footraces. What gave Cody’s show its appeal towards middle-class families was the mixture of these elements, which made the show realistic, educational, and child friendly, yet imbedded with subtle ideological messages on race, civilization, and social ideals. The aspect of order and safety desired by Cody was provided by his choice to employ ‘true western heroes,’ like himself and Bogardus. The display of Western heroes gave the show a sense of security and assured victory.

48

Conclusion

Two aspects of Manifest Destiny can be identified in Cody’s Wild West enterprise. First, the show promoted a subtle message of Anglo-Saxon supremacy by fielding an army of white American

46 “Program Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and the Congress of Rough Riders of the Worlds, 1893,” Folder 25, Box

13, Cody Collection Denver.

47 Ibidem.

48 Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West Show (New York: Vintage Books,

2005), 224-234.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

26

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age soldiers against a band of ‘red savages,’ played by real Native Americans. Second, the white army always defeated the band of red savages, thereby underlining the undeniable victory of Anglo-

Saxon civilization. Essentially, Cody’s show provided its audience with the same message as

O’Sullivan did; Anglo-Saxon civilization would eventually vanquish the inferior Native American race, because it was destined to be. American society believed in this inevitable victory, but was anxious about the inevitability of victory during the last two decades of the nineteenth century.

Cody’s show reminded American viewers of the superiority of Anglo-Saxon civilization and race and the inferiority of Native Americans, thereby soothing the doubts and fears of the audience for the time being.

It is incorrect, however, to see Manifest Destiny as a foundation for Cody’s show. It is true that there was a connection between central aspects of Manifest Destiny and the show, but this was not a straight forward connection. Cody had a specific audience in mind when he started developing his show; the middle-class family. In order to reach this audience, Cody had to adjust his show to the collective mind of American society and during the second half of the nineteenth century, this mind was in despair. With the closing of the Western frontier came a feeling of anxiety about the future of Anglo-Saxon civilization and American society. This resulted in a more radical interpretation of Manifest Destiny; the survival of Anglo-Saxon civilization had to be secured with force, which revealed itself in more aggressive policies towards Native Americans and the desire to transport American domination to other parts of the globe. Labeled as neurasthenia, this feeling of social insecurity developed itself throughout the decades after 1850, creating social tensions and a growing sentiment towards the western frontier, where true

American ideals could be identified. This sentiment provided Cody with the opportunity to create the entertainment enterprise he wished for.

It is difficult to make assumptions on Cody’s belief in Manifest Destiny, but it is possible to determine how significant it was to his show. And it was of a significant influence. Manifest

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

27

Chapter 1: America’s Entertainment in a Changed Age

Destiny enjoyed wide support by an insecure American society, regarding ideals on civilization and race. These aspects were cleverly imbedded in Cody’s show, yet is attracted the middle-class family as its primary audience. Manifest Destiny was not the primary foundation for Cody’s show, but it was a central aspect of its audience. Essentially, Manifest Destiny formed American society in way it became possible for Cody to create his show in a profitable way. The central aspects of race and civilization were represented in the show, but in combination with simple entertainment. It provided its audience with a mixture of fun, education, and a set of ideals that necessary to assure society on the ideals they supported by believing in Manifest Destiny.

The following chapter will focus on the role of Native Americans in the reenactment of their own defeat and the ‘inevitable’ victory of the Anglo-Saxon civilization. An interesting paradox emerges here; Native Americans joined Cody’s show, while it depicted the defeat of

Native American culture by the hands of Anglo-Saxon civilization. Why, then, did Native

Americans join the show, and which part did they play in the reenactment of the western frontier? Chapter two will provide answers to these questions, thereby adding to the context necessary for this research.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

28

Chapter 2: Representing a Vanquished Race

Chapter 2: Representing a Vanquished Race

“We stayed there and made shows for many, many Wasichus [white people] all that winter. I liked the part of the show we made, but not the part the Wasichus made. After a while I got used to being there, but I was like a man who never has a vision. I felt dead and my people seemed lost and I thought I might never find them again. I did not see anything to help my people. I could see that the Wasichus did not care for each other in the way our people did before the nation’s hoop was broken. They would take everything from each other if they could, and so there were some who had more of everything than they could use, while crowds of people had nothing at all and maybe were starving. They had forgotten that the earth was their mother.” 49

Black Elk, New York, 1886

Introduction

Since the first hiring of a band of Sioux-Oglala Indians for a theater production in 1877, more than a thousand Indian performers travelled with Cody’s Wild West show, who performed for millions of people in the United States and Europe. As performers, they received a paycheck and were provided with food and shelter, as well as with an education on ‘Wasichu society.’ The Native

Americans that traveled with the show were selected at auditions, organized on Native reservations. According to an eyewitness, identified by Nellie Shiner Yost as ‘Death Valley Scotty’ in her book Buffalo Bill: His Friend, Family, Fame, Failures, and Fortune, as many as 500 Indians attended the auditions for the 1884 and 1885 season in Rushville, Nebraska, to earn a place in

Cody’s company. Those who did not succeed in earning a sport seemed depressed about it.

During these auditions, Cody guaranteed the performers’ safety and well-being, as was required of him by Government officials.

50

The previous chapter has already established the significant role of Native performers in

Cody’s show by performing in some of its central acts. This chapter will focus on the specific roles

49 John G. Niehardt, Black Elk Speaks; Being the Life Story of a Holy Man of the Oglala Sioux (New York; State

University of New York press, 2008), 165.

50 Nellie Snyder Yost, Buffalo Bill: His Family, Friends, Fame, Failures and Fortunes (Athens; Ohio University

Press, 1979), 143.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

29

Chapter 2: Representing a Vanquished Race

Native American performers played and the ideological value of these roles. In other words, what did Native performers do and why? This brings any researcher on Native performers in Wild West show to face an undeniable obstacle; individual records or memoirs are scarce. Twentieth century publications on this topic are often based on a combination of records from non-Native performers, newspaper articles, and governmental documents, since these primary sources remain in greater quantity than personal histories from Indian performers.

Yet, it is possible to gain some insight in the life of Indian performers by combining the above mentioned sources with the few personal records of Native Americans that remain today.

One of these sources is John G. Niehardt’s Black Elk Speaks, a biography on Black Elk, an Oglala-

Sioux medicine man and performer in Cody’s show from 1886 till 1889. During this period, Black

Elk performed in the United States and in Europe, granting him the opportunity to educate himself in English and learn about white society. His records of this period as a performer can provide important information on the experiences of Indian performers, both in America and

Europe. 51

Another primary source of information is Sitting Bull, the legendary Lakota Chief who performed at Cody’s side in 1885. It is not personal memories that make Sitting Bull a source of information, but the fact so much has been written about him. He was a participant of the Battle at Little Bighorn, which made him a famous, yet notorious, historical figure in U.S. society. Nate

Salsbury, Cody’s entrepreneurial partner, mentions several interviews Sitting Bull gave to reporters, some of which he collected in his scrapbook that survived till this day. These interviews can provide essential information on the experiences of Native performers during their

51 L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque; University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 52-55.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

30

Chapter 2: Representing a Vanquished Race employment by Cody, the roles they played, and the way they lived their lives during the show’s seasons.

52

Which ideological values were expressed by Native performers in Cody’s show? This will be the central question of this chapter, which will consist out of three components. First, it will analyze the contribution of Native performers to the show program, by looking at the part Native performers played. Second, it will analyze the ideological message imbedded in the role Native performers played. Third, this chapter will analyze the life of Native performers behind the curtains. This last element is an essential component of the answer to the research question of paper; the opposition of Reformers towards Cody’s show was partly built on assumptions concerning the living conditions of Native performers outside their performances. The opposition of Reformers and the arguments they used will be central in the following two chapters, yet it is important to provide the context of their arguments in this chapter, since Native performers are central in it. In order to maintain a clear structure of this paper, this chapter will thus cover the three elements described above.

The time period cover in this chapter will be the years between 1885, the start of Cody’s enterprise, and 1893, the year in which his show took on an international shape and reached a highpoint in both size and popularity. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, personal records of

Indian performers have not survived history in great quantity, which makes a survey of the short period between 1889 and 1893, the primary period of this research, a difficult task. Furthermore, most of the prominent figures like Sitting Bull and Black Elk were involved in the show outside this timeframe, but provide important information nonetheless, which is why the period before 1889 is vital to this chapter.

52 Nate Salsbury scrapbook, Microfilm 1-4, Cody Collection Denver.; Robert M. Utley, Sitting Bull: The Life

and Times of an American Patriot (New York; Henry Holt&Co., 1993), 88, 122.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

31

Chapter 2: Representing a Vanquished Race

1883-1889

Since it inaugural performance on May 17 th , 1883, Cody’s Wild West show toured the United

States till March, 1887, after which it embarked on its first European tour. During this period, the show visited many of the larger cities, including a three month performance in New York’s

Madison Square Garden after the 1886 summer season.

53 This performance was a turning point in the show’s existence; it transformed from a ‘small’ circus-like show to an entertainment enterprise, performing both out- and indoors, but also stayed on the same locations for more than a month.

54

Sitting Bull

Between 1883 and 1889, Cody’s show achieved significant financial success and grew popular among U.S. citizens. This success can partly be explained by the presence of Sitting Bull during the

1885 season. Sitting Bull, a famous Hunkpapa-Sioux chief, was well-known throughout the United

States for his role in the famous battle at Little Bighorn, which explains why Cody was not the first entrepreneur searching to use Sitting Bull’s status to his own advantage. In 1884, Sitting Bull traveled some 25 cities across the East coast as a part of a travelling exhibition, commissioned by

Alvaren Allen, a business man from Minnesota and friend of Major James McLaughlin, who presided over the Standing Rock Indian Agency, where Sitting Bull lived. Allen’s tour proved to be a financial failure, which led to the refusal of McLaughlin to allow Sitting Bull to leave the reservation a second time. However, Cody’s career as a military scout had left him with some influential connections, which he used to his full advantage. After a positive reference from

General William T. Sherman, for whom Cody scouted in the 1860’s, McLaughlin allowed Sitting

53 Robert W. Rydell and Rob Kroes, Buffalo Bill in Bologna: the Americanization of the World, 1869-1922

(Chicago; Chicago University Press, 2005), 30.; L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American

Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque; University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 30-31.

54 Sarah J. Blackstone, Buckskins, Bullets, and Business: A History of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (Westport;

Greenwood, 1986), 16-19.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

32

Chapter 2: Representing a Vanquished Race

Bull and his family to join Cody’s Wild West show on May 18 th , 1885. According to Cody, Sitting

Bull had expressed a desire to join his show, although it is unknown why.

55

The above described turn of events provide insight in Sitting Bull’s hiring by Cody and on what terms. First, Sitting Bull was allowed to bring his family and some followers with him.

Second, Cody intended to treat Sitting Bull with respects and dignity. Yet it remains unknown why

Sitting Bull was suddenly allowed to leave the reservation after Cody’s first request was denied. A clue can be found in the 1885 annual report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John D.C.

Atkins to the Secretary of the Interior, Lucius Q.C. Lamar. In his report, McLaughlin describes positive achievements of ‘civilization’, yet he claims that “Sitting Bull’s retarding influence” 56 was an obstacle in reaching all Natives on the reservation. This is an intriguing statement. In combination with the previous rejected request from Cody, the references of General Sherman, and the promise of Cody to treat Sitting Bull with respect, one might come to the conclusion that the permission granted to Sitting Bull, his family, and some close followers to leave the reservation, was a political move from both Atkins and Lamar, aimed at removing an obstacle from the path of assimilation. Unfortunately, this assumption is bound to remain and assumption due to the absence of sufficient source material. It is possible to presume Sitting Bull was not fully cooperative regarding reservation policies, considering his involvement in the 1890 Ghost Dance uprising and the negative reports from McLaughlin. 57

The fact remains that Sitting Bull accompanied Cody’s show during its 1885 season from

June 12 till October 11 and became central figure of the show. A closer look at the 1885 show program can provide a better picture of the role Sitting Bull played in the show. The show existed

55 L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque; University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 25-27.; Louis Pfaller, “ ’Enemies in ’76, Friends in ‘85’ – Sitting Bull and Buffalo

Bill.” The Journal of National Archives 1 (1969):17-21.

56 John D.C. Atkins, Annual report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to the Secretary of the Interior, 1885

(Washington D.C.; Government Printing Office, 1885), accessed April 25, 2014, https://archive.org/stream/annualreportcom18affagoog#page/n288/mode/2up.

57 Moses, Wild West Shows, 26-27.; Louis S. Warren, Buffalo Bill’s America: William Cody and the Wild West

Show (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 379-381.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

33

Chapter 2: Representing a Vanquished Race out of twenty acts, divided in races, historic reenactments, and sharpshooting exhibitions. Sitting

Bull is not mentioned in the descriptions of these twenty acts, yet his life story is part of the program for educational purposes. Two pages of the 34 page program are devoted to Sitting Bull and the events that made him such a well-known figure in American society. The following passage is a fine example of the stature Sitting Bull enjoyed while touring the show; “he was noted as a hunter and warrior, and in early middle age he gained prestige as a Medicine Man (the

Sioux order of priesthood) and Counselor. By shrewdness, diplomacy and force of character he gained a lasting influence among his people, and became by common consent the consulting head of his nation. During the Big Horn expedition Sitting Bull was in command and of over five thousand warriors, and by his masterly control, and direction of their movements gained the title of the Napoleon of the Indian Race—after a series of battles that demonstrated his wonderful strategic powers.” 58

Noble savage

Sitting Bull appearance matched his role during the show; he was a not as much a performer as an object of display. This sounds degrading, but when placed in the context of respects and fame described above, it gives Sitting Bull’s role a more positive identity. Sitting Bull became the embodiment of “the noble savage,” 59 the counter perspective to the image of the red savage, embodied by the Indian warriors who performed in historical reenactments like the Attack on the

Deadwood Coach. Cody’s show provided its audience with both the image of the red savage and the noble savage, balancing the negative and positive images of Native Americans that existed in the late nineteenth century, and this balance persisted in the show thought its existence.

60

58 “Program The Wild West: Buffalo Bill’s Rocky Mountain and Prairie exhibition, 1885,” folder 19, Box 2,

Cody Collection Denver.

59 L. G. Moses, Wild West Shows and the Images of American Indians, 1883-1933 (Albuquerque; University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 3.

60 “Program The Wild West: Buffalo Bill’s Rocky Mountain and Prairie exhibition, 1885,” folder 19, Box2,

Cody Collection Denver.

Master Thesis American Studies W. de Jong 3475905

34

Chapter 2: Representing a Vanquished Race

The assumption mentioned above can be supported by a development in the show’s content. As the show expended in size and prepared to Europe, Indian performers began reenacting a variety of Native customs, manners, and dances, in order to represent Native civilization before they were ‘civilized’ by the Anglo-Saxon race. After the London exhibition in

1887 these Native representation became a more influential part of the show, as is proven by their presence on many advertisements for the show and the extensive information on Native society in the show programs. This development also supports the assumption on Cody’s effort to give his show an educational meaning.

61

Black Elk

Sitting Bull was the first famous Indian performer, but would not be the last one. In the summer of 1886, Black Elk, an Oglala-Sioux medicine man, joined Cody’s show for a tour through the

United States and its first tour the Europe, which started with the American Exhibition in London in 1887. Although Black Elk was not a well-known figure during the late nineteenth century, the fact that the German anthropologists John G. Niehardt published his biography in 1932 makes

Black Elk’s records of his time with the show a valuable source of information.