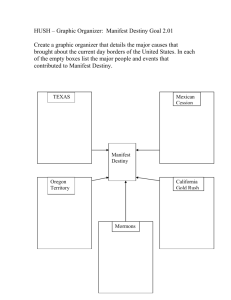

Concept Definition

advertisement

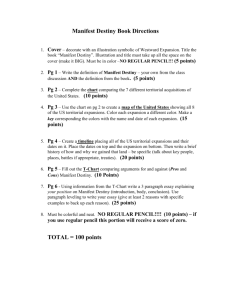

Clifton Lyddane Instructional Methods in Social Studies Professor Stoddard Concept Formation Lesson: Manifest Destiny Overview: I will teach this lesson in an eleventh grade history class. This lesson is designed to take most of, but not all of a ninety minute block. Students will participate in the definition of a concept through the process of concept formation. Too often students are expected to understand and apply concepts without having any practice using them. This lesson will have students work to define a concept from examples, and then give them practice categorizing samples as examples or non-examples of the concept. In this lesson students will define Manifest Destiny, learn some of the factual information from the mid to late 1800s that they will be expected to master, and learn about how the idea of Manifest Destiny continued to influential in America even after the United States had expanded from coast to coast. Rationale: Manifest Destiny is an important concept for students to master. The belief in manifest destiny can be used to organize a large amount of the information that students will be expected to learn on the second half of the nineteenth century. Students will also find knowledge of Manifest Destiny useful in tracing the development of American foreign policies up to the present day. Students will develop context for discussions of imperialism and American Exceptionalism. Students might also think about how contemporary American patriotism relates to the philosophy of Manifest Destiny. Learning about Manifest Destiny will also give students context for study of the treatment of immigrants and Native Americans in the United States. Knowledge of how these groups were treated in the nineteenth century gives students useful context for studying how policies towards immigrants and Native Americans have developed over the years. I have deliberately chosen my examples and counterexamples for the second portion of this lesson so that they are situated in the areas I have named above. When students reach those portions of the curriculum they will already have read something about them in this lesson. Studying this concept will give students a stronger hold on the history of the late nineteenth century, and will provide students with connections to other periods. Objectives and Supported Standards: Virginia SOLs: This lesson directly addresses VUS.8a, and provides valuable context for VUS.9a VUS.8a The student will demonstrate knowledge of how the nation grew and changed from the end of Reconstruction through the early twentieth century by explaining the relationship among territorial expansion, westward movement of the population, new immigration, growth of cities, and the admission of new states to the Union. VUS.9a The student will demonstrate knowledge of the emerging role of the United States in world affairs and key domestic events after 1890 by explaining the changing policies of the United States toward Latin America and Asia and the growing influence of the United States in foreign markets. NCSS standards: This lesson supports NCSS standards 1f, 3h, and 6c 1f) Students will interpret patterns of behavior reflecting values and attitudes that contribute or pose obstacles to cross-cultural understanding 3h) Students will examine, interpret, and analyze physical and cultural patterns and their interactions, such as land use, settlement patters, cultural transmission of customs and ideas, and ecosystem changes. 6c) Students will analyze and explain ideas and mechanisms to meet needs and wants of citizens, regulate territory, manage conflict, establish order and security, and balance competing conceptions of a just society. Objectives: Students will learn to examine a concept and define it carefully by working with their partner and with the whole class to define Manifest Destiny. Students will evaluate cases as examples or non-examples of the concept with their partner. For homework they will work individually to modify existing cases to change them from examples to non-examples or vice versa. Students will develop familiarity with the context of Manifest Destiny, and several of the key events of the second half of the nineteenth century by reading the examples and working alone and in groups to classify them. Assessment: Students will be assessed based on participation during the lesson and based on three assessment pieces. I will assess participation by watching students during the lesson and by collecting the worksheets provided. I will grade worksheets for completion. I will ask students to write a definition of manifest destiny using the three critical attributes defined in the lesson. Students will also rewrite an example of manifest destiny to make it a non-example, and a non-example of manifest destiny to make it an example. These three things will be submitted for homework. I will be able to tell from the assessment whether or not students have understood manifest destiny and are able to apply it to examples. If enough students are still having difficulties applying the concept I will re-teach manifest destiny at the beginning of another class, and tie it into the rest of the lesson. Content and Instructional Strategies: Introduction (three to five minutes) Introduce students to the type of lesson. Tell students that a concept definition lesson is designed to give them practice in analyzing text, and to give them practice applying the important concept that is the subject of this lesson. First example (five minutes) Provide students with first example. Students will work as a whole class to fill in worksheet. Make sure that as they answer the questions they will be able to deduce the critical attributes of the concept if they work the same way on the other questions. Second, Third, and Fourth examples (fifteen minutes) Students will work with partners to fill in the rest of the chart. Give them five minutes to work on each example. Circulate around the room to make sure that everyone is filling in their charts appropriately. Concept Definition (fifteen to twenty minutes) Have students confer with their partner on what the differences are between the examples and then list the differences between the different examples on the board as a whole class. Once students have run out of ideas ask them to look at what is on the board and see if anything sparks a new idea. Ask them to confer with their partner and then share with the class. Update the list on the board. Follow the same procedure with similarities. When students are looking for now ideas based on the ideas already listed on the board ask them to come up with crazy ideas. It may be necessary to draw students attention to similarities to make sure that the critical attributes are on the board. Definition (five minutes) Tell students the critical attributes of the concept. Circle their ideas on the board that support this definition. Manifest Destiny is: · The Belief in the particular virtue of American Culture. · The belief that American culture and influence should be spread (sometimes specifically from coast to coast) · The belief that the spread of American culture and power is in some way destined (possibly by God). Have students write a definition of manifest destiny in sentence form and have several students share their definitions with the class. Reveal the name of the concept. Context (five minutes) This will be an introduction to manifest destiny. Provide students with some background knowledge about the origin and influence of manifest destiny. Show them the John Gast painting and have them identify how it represents manifest destiny. Application (fifteen minutes) Students will work with their partner to discover whether or not the cases provided illustrate the concept of Manifest Destiny. They should justify each case using the critical attributes. Homework assignment and Debrief (five minutes) For homework or in the remaining time in class students will write down a sentence defining Manifest Destiny using the critical attributes that we developed as a class, and change an example to a non-example and a non-example to an example. Differentiation: This lesson provides some differentiation for students of different levels. I created the examples so that students who have difficulties pulling things out of them would get something. More advanced students will be able to glean more information from the examples. If I knew the class better and the layout facilitated it I might choose to have students work in small groups for part of the lesson instead of working with partners the whole time. This would allow me to create additional material for the advanced groups, and provide more support for the groups that needed it. This lesson is heavily text based. If I were to teach it again I would likely try to find more non-text examples for students to work with. The Gast painting could easily become one of the examples. Some students might have difficulties working with the cases. I could provide more scaffolding for those students. Adaptation: Students who need it could be provided with easier examples, or audio versions of the examples. I would also makes sure to provide students who need it paper copies of everything that is in the PowerPoint presentation so that they can follow along in front of them. Students that have difficulty working with other students could complete the partnered portion of this lesson alone, though they would not benefit from a partner’s additional perspectives. Reflection: In practice this lesson did not go as well as I expected it to, mostly due to time management issues and my inexperience. I will definitely try to use this type of lesson again, but I will attempt to structure the lesson better, and choose a topic that is more immediately valuable to students. I think that this lesson might work better with a concept that students have been exposed to, but do not have extensive experience with, rather than as an introduction to a concept. If I were to teach it again I would make sure to prepare more questions for students to draw information out of them to add to the board. A more experienced teacher might not need to do this, but I found that I was not getting the information that I knew that students had because I was not asking the right questions and students were not volunteering information. Another example of how my inexperience caused this lesson to go worse than it might have is that I did not prepare the lesson for the space I was teaching it in. When I designed the PowerPoint for this lesson I did not think enough about how it would work in the classroom where I was teaching this lesson. I thought that I had planned sufficiently, but when I got to the classroom I realized that I would have to turn the projector on and off to use the board. This slowed things down tremendously, and because I did not provide students with all of the cases in a handout they had to rely solely on their notes. If I taught this lesson again I would make sure that I could write on the board and keep the examples projected onto a screen at the same time, and I would provide the students with a paper copy of all cases if possible. The time management issue could also be attributed to inexperience. The classroom layout where I taught the lesson has the clock behind the teacher as he or she faces the class. I had a difficult time telling how long it had been since I told the students that had five minutes. This was exacerbated by the fact that the clock was digital. I think investing in an analog watch might help me with my time management until I have enough experience to work without relying on a clock. I also feel that I could do a better job with differentiation in this lesson. If I teach it again I will be sure to provide more variation in the types of sources, and provide everyone with paper copies of all the cases. Students were mostly divided into three groups as I taught the lesson: students that were following along, students that thought it was too easy, and students that weren’t interested at all. I feel that providing more some more complicated cases would help address the needs of the students that were moving through the lesson too quickly.