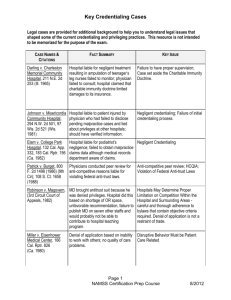

Poliner v. Texas Health Systems

advertisement

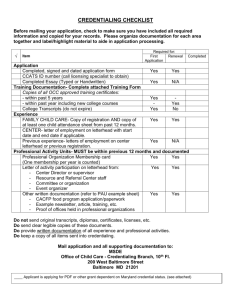

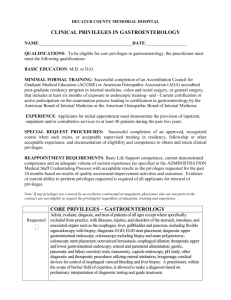

Negligent Credentialing/Privileging Christopher Droubay Snow Christensen & Martineau Not a Doctor…… In 1958, Gerald Barnbaum graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree from the University of Illinois College of Pharmacy. He worked as a pharmacist until 1976, when his license was revoked after he and 10 other people were arrested for Medicaid fraud. That same year, he changed his name from Gerald Barnbaum to Gerald Barnes, which was the same name as a practicing orthopedic surgeon, and moved to California. In 1978, he got a job as a physician at the Pacific Southwest Medical Group in Irvine. He worked for over a year until December 26, 1979, when 29-year-old John Alfred McKenzie went to see Barnbaum. McKenzie complained of dry mouth, suddenly weight loss, dizziness, and insatiable thirst. These symptoms point to uncontrolled diabetes, but instead of sending him to the emergency room, Barnbaum told him to go home and not to eat candy. McKenzie’s body was found two days later, after he died from complications related to diabetes. Not a Doctor…. Barnbaum was arrested and sentenced to three years for involuntary manslaughter and spent 18 months in prison. One would think that killing a patient and going to prison would be enough for him to stop the charade, but once he was released on parole, he started practicing medicine again. He was arrested twice more for practicing medicine without a license and identity theft and was sent back to prison. In 1995, he was out of prison and landed a job working at Executive Health Group doing physicals and checkups, where many of his patients were FBI agents. He was exposed within a year and arrested. He pled guilty to mail fraud and was given 10 years. However, during a prisoner transfer, Barnbaum escaped from the van, and again took up medicine while on the lam. He was arrested weeks later and another two and a half years were added to his sentence. He is currently set for release in 2018. A Little History Pennsylvania Hospital (1754) Benjamin Franklin Not for Profit Primarily a place to recover from surgery Medical practice came later Charitable Immunity Doctrine Privatization and Self-Regulation A Little History The healthcare system relies in large part on private credentialing bodies to certify and approve practitioners and healthcare organizations. This started in 1917 when the American College of Surgeons established a one-page list of minimum standards for hospitals and introduced a voluntary compliance system. In the 1950s, the ACS and its standards were replaced by the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Hospitals, now known as JCAHO. Today, JCAHO accredits more than 15,000 healthcare organizations and programs. THE BASICS Credentialing —the process of obtaining, verifying, and assessing the qualifications of a practitioner to provide care or services in or for a health care organization. • Educational and training background • Work history • Current licensure • References, and • Ability to perform the services / privileges requested. THE BASICS Credentials are documented evidence of licensure, education training experience, or other qualifications. Examples of credentials are: a certificate, letter, or experience that qualifies somebody to do something. They can be a letter, badge, or other official identification that confirms somebody's position or status. The organization can obtain verification of the LIP’s education, training, certificates and licensure from the primary source, and maintain the file of information. THE BASICS Privileging – the process whereby a specific scope and content of a patient care services (that is clinical privileges) are authorized for a healthcare practitioner by a health care organization, based on an evaluation of the individuals credentials and performance. • The specific patient care diagnostic or therapeutic procedures a physician or non-physician practitioner is permitted to perform in a specific facility. • Based on evaluation of the individual, the medical staff prepares recommendations to grant, deny, continue, revise, discontinue, limit, or revoke privileges, to the governing body. • Only the Governing Body has the authority to grant: 1) 2) Clinical privileges, after reviewing medical staff recommendations and / or Medical Staff membership THE BASICS A "privilege’ is defined as an advantage, right, or benefit that is not available to everyone; the rights and advantages enjoyed by a relatively small group of people, usually as a result of education and experience. THE BASICS Summary: Credentialing verifies the education and training. This allows your organization to grant privileges to a licensed independent provider to perform services for your organization. THE BASICS Primary Source Verification (PSV): • The verification of information directly from the original source. • Primary source verification is required to verify the accuracy of education, training, licensure, exams, and board certification information. THE BASICS Appointment and Re-appointment: A. Initial Appointment: The first appointment to the medical staff. Appointments may be no longer than 2 years, but may be less. B. Re-appointment: The medical staff must periodically re-appraise all professionals appointed to the medical staff / granted medical staff privileges to determine current competence. Purpose of appraisal: To determine suitability of continuing the medical staff membership or privileges. Reappraisal is to be conducted. Without renewal, practitioner is practicing without privileges (expired privileges). The medical staff appraisal procedures must evaluate each individual practitioner’s qualifications and demonstrated competencies to perform task / privileges. Legal Basics Different Theories of Liability are utilized Negligence Respondent Superior (Let the Master Answer) Apparent Agency Hospital-based physician, i.e., anesthesiologist, was thought to be a hospital employee and therefore hospital is responsible for physician’s negligence Direct Liability Including Negligent Credentialing Intentional Conduct Direct Liability- Negligent Credentialing Hospital issued clinical privileges to an unqualified practitioner who provided negligent care Hospital, along with its medical staff, is required to exercise reasonable care to make sure that physicians applying to the medical staff or seeking reappointment are competent and qualified to exercise the requested clinical privileges. If the hospital knew or should have known that a physician is not qualified and the physician injures a patient through an act of negligence, the hospital can be found separately liable for the negligent credentialing of this physician Legal Process in Utah DOPL Prelitigation Pleadings Discovery Interrogatories Requests for Production Depositions Trial Appeal The First Case- Darling Darling v. Charleston Community Memorial Hospital (1965) First case in the country to apply the Doctrine of Corporate Negligence Case involved a teenage athlete who had a broken leg with complications and was treated by a family practitioner Leg was not set properly and patient suffered permanent injury Hospital claimed no responsibility over the patient care provided by its staff physician Darling Court rejected this position as well as the charitable immunity protections previously provided to hospitals Part of the basis for the decision was the fact that hospital was accredited by the Joint Commission and had incorporated the Commission’s credentialing standards into its corporate and medical staff bylaws Darling These standards reflected an obligation by the medical staff and hospital to make sure physicians were qualified to exercise the privileges granted to them Physician was found to be negligent The medical staff and hospital’s decision to give privileges to treat patients with complicated injuries to an unqualified practitioner directly caused the patient’s permanent injuries. Therefore, the hospital was held liable for the damages Johnson Johnson v. Misericordia Community Hospital It was alleged that a physician on a Wisconsin hospital’s medical staff botched a hip surgery, causing paralysis. The patient sued not only the physician who performed the surgery but also the hospital, alleging that it failed to properly investigate the physician's credentials prior to appointing him to the medical staff. Johnson The Physician’s privileges were restricted, and in fact revoked, at some hospitals because of “fragrant bad practices.” The physician was never on the staff at some of the hospitals listed in his application for appointment. Contrary to statements in his application, the physician was not board-certified or board-eligible in the field of orthopedic surgery. The physician had 10 malpractice suits filed against him, seven of which occurred prior to his appointment at the hospital Peers believed him to be unfit Frigo Frigo v. Silver Cross Hospital (2007) Frigo involved a lawsuit against a podiatrist and Silver Cross Patient alleged that podiatrist’s negligence in performing a bunionectomy on an ulcerated foot resulted in osteomyelitis and the subsequent amputation of the foot in 1998 Frigo The podiatrist was granted Level II surgical privileges to perform these procedures even though he did not have the required additional post-graduate surgical training required in the Bylaws as evidenced by completion of an approved surgical residency program or board eligibility or certification by the American Board of Podiatric Surgery at the time of his initial appointment in 1992. Frigo Frigo argued that because the podiatrist did not meet the required standard, he should have never been given the privileges to perform the surgery. She further maintained that the granting of privileges to an unqualified practitioner who was never grandfathered was a violation of the hospital’s duty to make sure that only qualified physicians are to be given surgical privileges. The hospital’s breach of this duty caused her amputation because of podiatrist’s negligence. Frigo Jury reached a verdict of $7,775,668.02 against Silver Cross Podiatrist had previously settled for $900,000.00 Hospital had argued that its criteria did not establish nor was there an industry-wide standard governing the issuance of surgical privileges to podiatrists Hospital also maintained that there were no adverse outcomes or complaints that otherwise would have justified non-reappointment in 1998 Frigo Court disagreed and held that the jury acted properly because the hospital’s bylaws and the 1992 and 1993 credentialing requirements created an internal standard of care against which the hospital’s decision to grant privileges could be measured Court noted that Dr. Kirchner had not been grandfathered and that there was sufficient evidence to support a finding that the hospital had breached its own standard, and hence, its duty to the patient This finding, coupled with the jury’s determination that Dr. Kirchner’s negligence in treatment and follow up care of Frigo caused the amputation, supported jury’s finding that her injury would not have been caused had the hospital not issued privileges to Dr. Kirchner in violation of its standards Frigo In Frigo, hospital’s attempt to establish that duty was met by showing, through the peer review record, that podiatrist had no patient complaints or bad outcomes was denied because prohibition on admissibility into evidence was absolute. Court stated, however, that this information was somewhat irrelevant because the Hospital clearly did not follow its own standards. Meyer In Meyer, et al. v. Health Plan of Nevada, Inc., et al., Case No. A5832799 (Clark County, NV), three plaintiffs brought claims for common law negligence and loss of consortium against the Plans, as well as United Healthcare Services Inc. and other affiliated companies, claiming that they contracted Hepatitis C after receiving treatment from Dr. Dipak Desai at the Endoscopy Center of Southern Nevada (Clinic). The factual support for the plaintiffs’ claims emanated from the Southern Nevada Health District tying the outbreak to “unsafe injection practices,” including the alleged re-use of syringes and medication vials, at the Clinic and other clinics owned by Desai. Meyer Plaintiffs alleged the Plans had a duty to “direct, evaluate, and monitor the effectiveness of healthcare services provided by the Clinic to [their] insureds,” including to establish and implement a “quality assurance program designed and utilized to provide quality health care services.” Plaintiffs also contended that the Plans breached that duty because they knew, or should have known, about the substandard conditions and unsafe practices at Desai’s Clinics for multiple reasons. Meyer (1) Desai had a reputation for performing colonoscopy procedures faster than any other physician in the area; (2) a competing doctor allegedly reported incidents of malpractice to HPN years before the incident; (3) HPN allegedly paid Desai too little to perform the procedures at any profit; and (4) in 1992, HPN dropped Desai from its network citing quality concerns, yet reinstated him five years later. Plaintiffs further contended that the Plans breached their duties to the plaintiffs by failing to discover the improper conduct and prevent plaintiffs from receiving treatment form Desai. Meyer The Plans argued that no common law duty-imposed obligations apply above and beyond Nevada’s regulatory requirements and that they complied with all Nevada statutes because their quality improvement programs were accredited by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) as “commendable,” meaning a plan “meets or exceeds [NCQA’s] rigorous requirements for consumer protection and quality improvement.” Moreover, the Plans argued that the Clinic was accredited by the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care (AAAHC), pursuant to which the AAAHC conducted on-site inspections of the Clinic and interviewed Clinic staff. Based upon meeting those industry-standard accreditations, the Plans argued that they could not have breached any duty as a matter of law. Meyer Based upon meeting those industry-standard accreditations, the Plans argued that they could not have breached any duty as a matter of law. The court rejected that argument and the jury found the Plans to be negligent for failing to properly monitor Desai’s practice and awarded $24 million in compensatory damages and assessed a total of $500 million in punitive damages against both companies. Meyer On appeal, the court noted that it had not formally recognized the tort of negligent credentialing but that 40 years earlier it had observed that hospitals have a duty to take steps to ensure patient safety in the process of accreditation and granting of privileges. The court also noted that it recognizes analogous torts, such as negligent selection or hiring of an independent contractor. Finally, the court acknowledged that at least 30 other states recognize the tort of negligent credentialing. Meyer The Court concluded: Based on these authorities, we are persuaded that the "gradual evolution" of the common law supports the recognition of the tort of negligent credentialing. Sacco, 271 Mont. at 234, 896 P.2d at 426. We therefore recognize negligent credentialing as a valid cause of action in Montana. Similar to a medical malpractice claim, a plaintiff in a negligent credentialing action must establish the following elements: "(1) the applicable standard of care, (2) the defendant departed from that standard of care, and (3) the departure proximately caused plaintiff's injury." Estate ofWillson [v. Addison, 2011 MT 179, ¶ 17, 361 Mont. 269, ¶ 17, 258 P.3d 410, ¶ 17]. Brookins v. Mote In Brookins v. Mote, 2012 MT 283, ___ P.3d ___ (not yet released for publication), an expectant mother hired an obstetrician who maintained a practice in his home. The obstetrician ("Dr. Mote") had previously resigned his position at Mineral Community Hospital ("the Hospital") and pleaded guilty to misdemeanor sexual abuse of a child. The Montana Board of Medical Examiners had placed the doctor on probation and prohibited him from treating minor patients unless a third party was present. Aware of these facts, the Hospital declined to rehire him as an employee but did extend credentials for him to use the Hospital's facilities as an independent physician. Brookins Medical problems persisted during the pregnancy and after delivery, and a medical malpractice action was filed against the Hospital and Dr. Mote. The complaint alleged that the doctor had had unauthorized sexual contact with the baby during delivery, examination, and subsequent circumcision. A claim for negligent credentialing was asserted against the Hospital. Following a settlement with Dr. Mote, the trial court granted summary judgment for the Hospital. Basis of Negligent Credentialing Cases: Negligent information gathering and verification Failure to follow reasonable internal credentialing procedures (Bylaws) Failure to follow standards of accreditation, licensing, CMS Conditions of Participation, State regulations on Peer Review, or other applicable requirements Basis of Negligent Credentialing Cases: Failure to assess the credentialing information reasonably by the medical staff Negligent granting or failure to limit privileges to an unqualified physician Failure to take appropriate, remedial or corrective action based on the credentialing/privileging information Basis of Negligent Credentialing Cases: Documentation “If it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done.” Pitfalls Scant documentation Missing documentation Evidence of Evaluative Process Forms not checked off, dated, or signed Incomplete applications Basis of Negligent Credentialing Cases: Desperation (I need a warm body) Don’t be rushed into the appointment process Utah Law Archuleta v. St. Mark’s Hospital The patient, Tina Archuleta, had laparotomy surgery in 2005, which was performed by Dr. R. Chad Halversen at St. Mark’s Hospital. Two days later, Archuleta was hospitalized with severe pain and complications from the surgery, and in the next year, she had over six corrective surgeries. In her lawsuit, Archuleta asserted a claim against the hospital for negligent credentialing of Halversen, based on the hospital’s alleged failure to properly screen or review the surgeon’s competency, skills and abilities or the hospital’s allegedly allowing a known incompetent surgeon to access its surgical facilities. The district court rejected that claim on statutory grounds, and Archuleta appealed. Archuleta vs. St. Marks Hospital Bad facts often make bad law District Court dismisses negligent credentialing claim based on three Utah statutes: 58-13-5(7), 58-13-4, 26-25-1 Archuleta vs. St. Marks Hospital Patient Archuleta appeals to Utah Supreme Court Utah Supreme Court reverses District Court and creates new cause of action in Utah of negligent credentialing on a 32 vote Majority Supreme Court opinion states that “the plain language of the statutes does not bar a negligent credentialing claim” Strong minority opinion that the plain language of these statutes does bar negligent credentialing claims What Do You Think? Plain language of the statute 58-13-5(7) “(7) An individual who is a member of a hospital administration, board, committee, department, medical staff, or professional organization of health care providers . . . . And any hospital, other health care entity or professional organization conducting or sponsoring the review, is immune from liability arising from participation in a review of a health care providers professional ethics, medical competence, moral turpitude or substance abuse.” Archuleta vs. St. Marks Hospital The suit involved the interpretation of Utah Code §§ 58-13-5(7), 58-13-4, and 26-25-1, all part of the state’s statutory scheme governing health care information. The Supreme Court addressed each statute section in turn. The first provision, Utah Code § 5813-5, compels a health care facility to report certain events, such as the termination of employment or restrictions of privilege for cause, violations of professional standards or ethics, or incompetency, that affect a licensed health care provider’s practice or status. The court held that the plain language of § 58-13-5 shows that it involves peer review. “The immunity contemplated under the statute operates between a doctor whose credentials are under review and the suppliers of information and decision-makers; it does not contemplate immunity between a patient and a hospital,” the court said. Archuleta vs. St. Marks Hospital The second provision, § 58-13-4, grants immunity to health care providers that sponsor or make decisions regarding the proper use of facilities, the quality and cost of health care, ethical standards, or performance of services. The court found that the legislature expressly used language in § 58-134 that excluded patients’ claims regarding care. “The credentialing determination is a decision regarding a doctor’s fitness to provide patient care—and is clearly covered by the language of the exception that protects patients’ claims regarding provision of that care,” the court held. - Archuleta vs. St. Marks Hospital The court then found that the third provision, § 26-25-1, which grants immunity for the dissemination of information or materials, bolstered the “plain language reading of limited immunity” of the other two code sections. “Again, under the plain language of this section, the legislature’s grant of immunity relates to the dissemination of information, not to patient care.” Legislative Remedy Utah health care entities and health care providers had relied on this language for decades to bar a claim for negligent credentialing – in fact, Utah courts had as well until the Archuleta ruling Only way to really change the Supreme Court common law creation of this claim was to go back to the Legislature to clarify Strong coalition of all major health care associations, led by UHA, supported S. B. 150 S.B. 150 – Negligent Credentialing Concise and clear language is the best S.B. 150 is one of the shortest laws ever passed in Utah S.B. 150 says in total “It is the policy of this state that the question of negligent credentialing, as applied to health care providers in malpractice suits, is not recognized as a cause of action.” Legislative Debate “Worst” Senate debate, got off track “hospitals will now hire pedophile physicians” Passed Senate on votes of 21-6 and 18-4 “Best” House debate of over an hour, very good discussion from both states as to the legal, practical and financial implications of this bill. Passed House 54-20 Governors Reaction Normally when you pass bills by a veto proof (2/3 majority) the odds are very high that a Governor will sign the bill Governor waited until near the end of his signing period to sign this bill due to strong lobbying of him by opponents of the bill Media Reaction There was a fair amount of media interest in this bill – mainly due to trial lawyers opposition to the bill There were a number of newspaper articles and editorials critical of the bill Coverage was generally fair when the media worked to get both sides of the story Plantiffs Lawyers Reaction Opposed the bill all the way to the end They will now look to the courts for a new remedy Current make up of Utah Supreme Court gives them hope that under the right case they may be able to overturn S.B. 150 on constitutional grounds under the “open courts” provision of the Utah Constitution As with all legislation that has passed the legislation, it is the state law unless, or until, overturned or interpreted differently by the Utah Supreme Court Plantiff’s Lawyer Reaction Don’t worry about that – prior laws we have passed have generally been upheld, and it has taken as long as 17 years for the “right” case to get to the Supreme Court Supreme Court can’t just rule on a law, it has to come to them through the normal court process, which can take years if not decades, as the history of negligent credentialing shows Nothing to Worry About? For your own financial, reputational, operational and legal benefit, continue to have a very robust credentialing process to weed out or stop problem providers Negligent Credentialing goes far beyond direct causes of action Respondent Superior Apparent Authority Fair Hearing Issues Other types of lawsuits PATIENT CARE AND SAFETY Don’t be the case that overturns the Statute. Kadlec Medical Center v. Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (“LAA”) Kadlec Medical Center v. Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (“LAA”) Kadlec Medical Center, in Richland, Washington, brought suit against LAA, the LAA shareholders, and Lakeview Regional Medical Center (“defendants”) because they failed to disclose Dr. Berry’s on-duty use of narcotics in response to Kadlec’s reference request. Dr. Robert Berry, an anesthesiologist and former shareholder of LAA, worked at Lakeview Medical until he was caught using Demerol at work. He failed to answer a page while on-duty at the hospital and he was discovered in the call-room, asleep, groggy, and unfit to work. He was fired soon thereafter. Kadlec Medical Center v. Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (“LAA”) After being terminated by Lakeview Medical and LAA, Dr. Berry sought work at Kadlec Medical Center through Staff Care. Upon receiving his application, Kadlec began its credentialing process and examined a variety of materials, including referral letters from LAA and Lakeview Medical. LAA’s Dr. Preau and Dr. Dennis, two months after firing Dr. Berry for his onthe-job drug use, submitted referral letters for Dr. Berry to Staff Care, with the intention that they be provided to future employers. Kadlec Medical Center v. Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (“LAA”) The letter from Dr. Dennis stated that he had worked with Dr. Berry for four years, that he was an excellent clinician, and that he would be an asset to any anesthesia service. Dr. Preau’s letter said that he worked with Berry at Lakeview Medical and that he recommended him highly as an anesthesiologist. Dr. Preau’s and Dr. Dennis’s letters were submitted on June 3, 2001, only 68 days after they fired him for using narcotics while on-duty and stating in his termination letter that Dr. Berry’s behavior put “patients at significant risk.” Kadlec Medical Center v. Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (“LAA”) Kadlec also sent Lakeview Medical a request for credentialing information about Dr. Berry. The request included a detailed confidential questionnaire, a delineation of privileges, and a signed consent for release of information. Lakeview Medical responded to the requests for credentialing information about 14 different physicians. In 13 cases it responded fully and completely to the request; however, the response concerning Dr. Berry was handled differently. Lakeview Medical drafted a short letter that stated: This letter is written in response to your inquiry regarding [Dr. Berry]. Due to the large volume of inquiries received in this office, the following information is provided. Our records indicate that Dr. Robert L. Berry was on the Active Medical Staff of Lakeview Regional Medical Center in the field of Anesthesiology from March 04, 1997 through September 04, 2001. If I can be of further assistance, you may contact me at (504) 867-4076. Kadlec Medical Center v. Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (“LAA”) The letter did not disclose LAA’s termination of Dr. Berry; his on-duty drug use; the investigation into Dr. Berry’s undocumented and suspicious withdrawals of Demerol that “violated the standard of care”; or any other negative information. Kadlec then credentialed Dr. Berry, and he began working there. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Berry was in a car accident and suffered a back injury. After the accident, nurses began to notice he appeared sick and exhibited mood swings. Several months later, Dr. Berry gave a patient too much morphine during surgery, and she had to be revived using Narcan. The neurosurgeon was irate about the incident. Kadlec Medical Center v. Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (“LAA”) On November 12, 2002, Dr. Berry was assigned to the operating room beginning at 6:30 a.m. He worked with three different surgeons and multiple nurses well into the afternoon. According to one nurse, Dr. Berry was “screwing up all day” and several of his patients suffered adverse affects from not being properly anesthetized. Kimberley Jones was Dr. Berry’s fifth patient that morning. She was in for what should have been a routine, fifteen minute tubal ligation. When they moved her into the recovery room, one nurse noticed that her fingernails were blue, and she was not breathing. Dr. Berry failed to resuscitate her, and she is now in a permanent vegetative state. Kadlec Medical Center v. Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (“LAA”) Dr. Berry confessed he had been using Demerol since his car accident and that he had become addicted to Demerol. Jones’ family sued Dr. Berry and Kadlec, and both Dr. Berry’s and Kadlec’s insurers settled the claims. In this case, Kadlec and its insurer have filed suit against LAA, Dr. Dennis, Dr. Preau, Dr. Parr, and Lakeview Medical alleging intentional misrepresentation, negligent misrepresentation, strict responsibility misrepresentation, and general negligence. Kadlec Medical Center v. Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (“LAA”) In the lower court, a jury found Lakeview Medical and the three shareholders/doctors of LAA liable. The court held that, in order to protect future patients of an impaired physician, Lakeview Medical and its physicians had a duty to disclose Dr. Berry’s impairment to a second hospital where the physician relocated and applied for privileges. On appeal, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals held that: the defendants, after choosing to write referral letters, assumed a duty not to make affirmative misrepresentations in the letters. the doctors’ reference letters were misleading, while the letter from Lakeview Medical was not. the defendants had no affirmative duty to disclose negative information about Dr. Berry in their referral letters. Lakeview Medical did not breach any duty owed to Kadlec, and therefore the judgment against it was reversed. Although Lakeview Anesthesia Associates (LAA) put Dr. Berry on notice and ultimately fired him for use of Demerol and endangering patients, partners wrote glowing letters of recommendation in respone to Kadlec’s peer reference request. Provide correct information when responding to verification requests Don’t omit key information when providing verifications Address letter to Credentialing and/or MEC Sign as Agent of MEC Additional Pointers: Do not feel the need to stay within the form used for the reference request; Do not respond to verbal requests for references or provide information via email or telephonically; Confirm every answer made with documentation in file; and Do not rush to complete the reference request and do have it reviewed before it is submitted. Beyond “Traditional” Negligent Credentialing Poliner v. Texas Health Systems (5th Cir. 2008) Multi-Million Damages Award to physician reversed by appeals court. Hospital and Peer Review Committee Member entitled to immunity where Hospital complied with HCQIA, notwithstanding failure to comply with Hospital Bylaws. Poliner v. Texas Health Systems (5th Cir. 2008) Facts: Dr. Poliner, cardiologist, was granted temporary privileges at Hospital in 1996 and obtained full privileges in October 1997. However, questions about quality of care began to arise in September 1997 following a patient death after procedure in cath lab. Dr. Poliner’s cases were under review by Clinical Risk Review Committee (“CRRC”) when, on May 12, 1998, he misdiagnosed a patient and performed angioplasty to wrong artery, leaving the blocked artery untouched. Poliner v. Texas Health Systems (5th Cir. 2008) The next day, on May 13, 1998, Dr. Knochel, head of Department of Internal Medicine, requested Dr. Poliner to agree to “abeyance” for fourteen days to allow investigation. Hospital Bylaws required consent. Dr. Knochel told Dr. Poliner that if he refused to agree to abeyance, he would suspend privileges. Dr. Knochel testified at trial that at time of compulsory abeyance, he did not have enough evidence to determine if Dr. Poliner was a present danger to patients. On June 12, Hospital suspended Dr. Poliner’s privileges. Poliner v. Texas Health Systems (5th Cir. 2008) Issue: Damages at trial based solely on forced abeyance of May 13, 2009. Jury found no agreement as required by Hospital Bylaws. Jury found abeyance did not meet HCQIA standards for 14 day suspension in case of health emergency because Dr. Knochel testified that he did not have enough information to determine if Dr. Poliner was a present danger. Poliner v. Texas Health Systems (5th Cir. 2008) Holding: (1) HCQIA immunity applied. (2) 14 day HCQIA requirement satisfied - decision made before May 14 even though Hospital did not request Poliner’s consent to extension of abeyance until day 15. (3) Hospital met “imminent danger” standard based upon CRRC’s determination that Poliner had provided substandard care in half of cases reviewed plus seriousness of mistake in clinical judgment resulting in misdiagnosis and error in treatment of patient the day before the abeyance. Poliner v. Texas Health Systems (5th Cir. 2008) (4) HCQIA “reasonableness requirements” were intended to create objective standard of performance, rather than subjective good faith standard. (5) Focus of reasonableness standard is not whether peer review committee’s decisions were correct or even whether peer review committee had bad motives. Instead, focus should be on whether decision was reasonable based upon facts known at that time. Poliner v. Texas Health Systems (5th Cir. 2008) Lessons Learned: 1. Be diligent about time limitations for emergency suspensions. 2. Emergency suspensions based upon “imminent danger” must be based on reasonable belief and based upon facts. Beyond “Traditional” Negligent Credentialing Rebecca, a surgical nurse, filed a suit against Dr. Michael and St. Vincent’s Hospital. Ms. Farr alleged Dr. Michael gripped her in a bear hug, held on to her while she thrashed to get away, rubbed his body against her chest, and actually reached down into her scrub top and pulled it away from her body so that he could stare down at her chest. Previously, at a different hospital, Dr. Michael had taken a staple gun and stapled a nurse’s forehead and forearm when she angered him. Ms. Farr is suing St. Vincent’s for its negligent hiring, training, and retention of Dr. Michael.