BOB_Combined_Working_GG - Washington University in St

advertisement

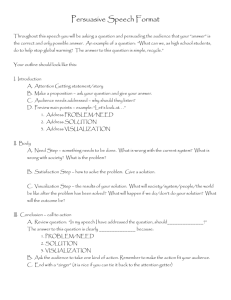

1 BOB*: A model for understanding the effect of visual design principles on persuasive communication and data visualization. Kassandra Alcaraz, MPH1 Chris Casey, BA1 Heather Corcoran, MFA3 Tina Clarke Dur, PhD2 Giovanina Gardiner, MSW1 Kim Kaphingst, PhD1 Matt Kreuter, PhD1 Doug Luke, PhD1 Lisa Moy, 2 Enrique VonRohr, MFA3 Andrea Spray, BA1 Author affiliations: 1 George Warren Brown School of Social Work and Public Health Washington University in St. Louis, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box 1009, St. Louis, MO 63130 2 3 Northern California Cancer Center 2201 Walnut Avenue #300 Fremont, CA 94538 Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts Washington University in St. Louis, One Brookings Drive, Campus Box XXXX, St. Louis, MO, 63130 2 ABSTRACT Public health professionals today have access to more data, better analytic and visual design tools, and more channels through which to share that information with diverse audiences. Strategic deployment of these data and data-related tools is needed to maximize their social impact in improving the health of populations. To help guide these efforts, we propose a new model that integrates principles of information design, information processing and persuasive communication to understand how health data may influence non-scientific audiences. The model introduces three major principles of information design (hierarchy, micro and macro, consistency and variation) and describes how each might affect information processing and persuasion, specifically attention, understanding and elaboration. Contextual factors and moderating variables that may influence these relationships are also discussed. We assert that the model will help communication planners use data more purposefully and effectively, and call for research to test and refine its propositions. KEY WORDS: Information design, visual design, information processing, health communication, cancer communication, visual displays, transdisciplinary model, data visualization, persuasion, public health 3 INTRODUCTION (Doug Luke) (1-2 pages) Problem and opportunity statement The general public is increasingly exposed to sophisticated visual displays of data. The nearly ubiquitous interactive electoral maps used on cable television news during the 2008 U.S. presidential election illustrate this trend. Arguably, leading media outlets use more effective data visualization approaches than many public health scientists and organizations. To keep pace, public health professionals must develop clear and compelling ways to share new knowledge with the public and other audiences. Visual display of quantitative information is the art and science of presenting data in ways that make them more engaging, understandable and meaningful, and enhance their impact on the viewer. It spans media and can incorporate words and pictures, graphs, charts, maps, and other visual devices. Done well, visual displays can transform quantitative information from an abstract numerical form into a more visceral and sensory experience. They use a direct and intuitive visual language to show relationships, structure and change, and have distinct advantages in communicating complex ideas with clarity and efficiency. For example, they can simultaneously reveal multiple levels of detail (e.g., data for a city block and all blocks in the city), changes over space (e.g., counties, states, regions) and time (e.g., annual rates), and multivariate complexity (e.g., combining all of these in a single spatial display, by demographic characteristics). Many government and other health agencies have built major infrastructure for collecting and analyzing population health data (e.g., the National Cancer Institute’s SEER). Less attention has been paid to maximizing the impact of these data through communication science. Strategic 4 presentation of health statistics and other surveillance data to the public, policy makers and news media may increase awareness and social action for public health. Cancer registry data are underutilized for both descriptive (e.g., production of cancer statistics) and analytic (e.g., as a resource for recruiting patients into more detailed research studies) purposes. Most cancer registries produce a standard roster of statistics – rates and trends, often with rudimentary graphs or other data visualization – and disseminate these to scientific and professional audiences. Dissemination to the public, policy makers, news media, and other non-scientific audiences is less common and less systematic. What is needed is a more strategic, sophisticated approach to communication with lay audiences. Such an approach would start with a clear articulation of the main message a given set of data is intended to convey and the broader goals it will advance (e.g., population awareness, increased screening, policy advocacy). It would consider not just the types of cancer data to be presented, but also to whom they would be presented, and what we know about how that audience uses and understands cancer information. (CAN BE AN EXAMPLE? OR REMOVE?) Cancer registration is mandated in all 50 states. Cancer registry data are the only truly population-based and therefore representative resources for quantifying cancer morbidity and mortality. However, When it occurs, it is often reactive (e.g., responding to a cancer cluster concern in a neighborhood), although several states and the NCI have made interactive online mapping tools available to the public. 5 Our goal with this paper: to introduce a transdisciplinary model for thinking about cancer data visualization. OVERVIEW OF THE MODEL (Matt Kreuter) (1/2 – 1 page) Developing the model Modern visualization tools and interactive media offer the ability to create novel representations of geospatial cancer data, but these approaches still need to be tested, evaluated, and refined. To do this requires a new collaborative team of epidemiologists, experts in design and development of visual displays of quantitative information, and cancer communication researchers. Focus on the box in the diagram In creating a transdisciplinary model to better understand cancer data visualization, we drew from three disciplines (scientific data analysis, visual design, and communication). This project aims to develop a more comprehensive, strategic and evidence-based approach to visualizing and presenting data. In short, data visualization would be guided by a systematic framework that builds on the science of cancer communication and the art of visual display to maximize accessibility, understandability and social impact of cancer data. INFORMATION PROCESSING MODELS (Kim Kaphingst) (1/2 – 1 page) Much of the contemporary research on persuasive communication is based on the early work of McGuire (1968) and his input/output model of persuasive communication.93 This model, later termed the Communication/Persuasion Model27 consists of five types of “input” variables (source, message, channel, receiver and destination) that can influence effectiveness of a 6 communication, and 12 possible “outputs,” or outcomes of communication (e.g., attention, comprehension, attitude change). In the model, these 12 outcomes are successive, from more affective and cognitive effects to behavioral outcomes. McGuire proposed that for a communication to achieve higher order effects (e.g., behavior change), outcomes appearing earlier in this succession have to be achieved.27 For example, the model would suggest that health information, including data, will be more likely to influence audience members’ attitudes, decisions and actions if they are exposed to the communication, pay attention to it, understand it, and learn from it. The progression of communication effects can stop anywhere in this sequence.94 Thus, persuasive communication that hopes to achieve higher order effects should be designed to maximize effectiveness at each step. Petty and Cacioppo’s (1981) elaboration likelihood model (ELM) provides an explanation of how movement through these steps occurs. The ELM is based on the premise that under many conditions, people are active information processors -- considering messages carefully, relating them to other information they’ve encountered, and comparing them to their own past experiences.21-22 For example, people are more motivated to actively and thoughtfully process information if they perceive it to be personally relevant or if they care about the topic or issue being addressed.20 Studies have shown that when information is processed more deeply (i.e., “elaborated” upon) it is retained for a longer period of time and is more likely to lead to permanent change.23-24 Borrowing from these well-established and empirically supported theories of communication, persuasion and information processing, our model includes a sequence of attention, understanding and elaboration to describe the general process through which exposure to health 7 information can influence outcomes like knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behaviors (see Figure X). Attention Capturing Holding When do we want to capture / hold attention? What problems might this be relevant to? (Ask this question for next two concepts as well) Our initial concern with this model was in the ways that visual design may impact the end user’s desire to attend to the message (capturing attention) and in the maintaining attention. For the purpose of communication, attention is a necessary predecessor to understanding, and ultimately elaboration and increased motivation to positively impact behavior. Understanding Understanding Elaboration Personal relevance Motivation to process Favorable feelings How much does this relate to me? Dependent on cues from the message but also might be dependent on individual characteristics 8 Consistency and variation seem to have the biggest impact Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs Integration – the outcome PRINCIPLES OF VISUAL DESIGN (Heather Corcoran, Enrique VonRohr) (3-6 pages) Hierarchy Contrast: color, “one versus another” but also may be scale contrast Scale: Relative size to other objects, thus making object large or small. Color: Or Hue, Includes use of or change value, intensity, shade, tint and saturation. Colors can be primary, secondary, tertiary, complimentary or analogous. Weight: Tufte’s maximizing data; typographic (density of page) Grid: A grid is a network of lines use as a tool for generating form, arranging images, and organizing, information. It is not seen but rather is used as guide. Impacts both attention and understanding: examples (color can capture attention, intensity of colors can encourage end users to look more closely, which paves the way for increasing understanding. The use of intense hues can enhance understanding; for example, darker hues may indicate greater values) Macro & Micro Figure/ground: A figure (form) in relation to what surrounds it (ground, or background). Framing: What content you elect to highlight. Layers: Multiple number or levels of information in one visual. Transparency: Visual technique, name suggests meaning although an opaque set of images can imply transparency 9 Impacts understanding Consistency & variation Small multiples: parsing information into “easy sequences” Compare/contrast: something small versus something big Impacts understanding and elaboration FIGURE 1. (Design team creates) USING ACTUAL VISUALS Hierarchy • expected outcomes Micro & Macro • Expected outcomes Consistency & Variation • Expected outcomes APPLYING THE MODEL (1-2 pages) Context Data formulation (TINA CLARKE DUR) Prioritize and organize data Determine degrees of localization How do you select a good data story? Communication objectives (CHRIS CASEY) Message you want to communicate Audience analysis (MATT KREUTER) Who you are communicating to (constructing personas) 10 Audience background (SES, prior knowledge, learning style) Moderators (ANDREA SPRAY) The capacity of the visual principles listed above to enhance attention, understanding and elaboration will only be realized if the visualization is appropriate for the user (i.e., the person consuming the information) and the environment (i.e., where she is exposed to the visualization). Knowing who will use the visualization, and in what environment, drives decisions about factors that, while invisible to the user, can nonetheless enhance or diminish the visualization’s effect on attention, understanding, and elaboration. These moderating factors form the armature over which the visualization is draped. Channels For the purpose of this article, channel is defined as the media format by which the user may be exposed to the visualization and includes television, the Internet, print, radio, and telephone. It is selected based on a number of factors including knowledge about the target audience. The channel must be appropriate for the target user in order for him to even be exposed to the visualization. However visualizations must also be appropriate for the channel; a visualization that is effective in one channel may not be effective in another (6). Interactivity Interactivity is a quality of visualization on a spectrum from low to high. Interactivity most strongly correlates to attention, as a target user must at least cognitively interact with even a print visualization in order to facilitate cognitive processing. As the visualization increases in 11 interactivity it must incorporate appropriate affordances, “those fundamental properties that determine just how the thing could possibly be used”, that provide clues to its operation (1). Explanation Explanation, for the purposes of this article, is defined as supplementary narrative that describes the data contained in the visualization and contributes to understanding. The explanation can either lie outside of the visualization or be encompassed by it and it can take various forms including audio or text. Usability Underlying all of these factors is the usability of the visualization, the degree to which “people who use the product can do so quickly and easily to accomplish their own tasks” (5). Usability impacts each stage of the information-processing model and has a cumulative effect as the user progresses from one stage to the next. The data contained in the visualization cannot well be understood if the interface itself is standing in the way. Usability is commonly associated with five key principles: accuracy, ease of use, efficiency, learnability, memorability and user satisfaction (4). Moreover, in the field of health, credibility of the data source also plays a significant role and will be included for the purposes of this article. The particular usability heuristics change depending on the channel. CONCLUSION (Matt Kreuter and Tina Clarke Dur) Call for research 12 Currently, best practice guidelines for presenting geo-coded cancer registry data are available from the North American Association of Central Cancer Registries.[4] This handbook describes cartography basics, types of maps and media, and how to match data with presentation mode. These guidelines are very helpful, but base decisions about visual display on characteristics of the data, rather than the communication goals of the display. Just as health communication has examined textual elements of communication, we can and should be analyzing visual elements All propositions laid out within this paper still need to be empirically tested Implications for practice (Tina) If you’re in the business of communicating data, you should be using these guidelines References National Cancer Institute: Geographic Information Systems – Overview of GIS at NCI. 2009. National Cancer Institute: The NCI strategic plan for leading the nation to eliminate the suffering and death due to cancer Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Senior Service National Institutes of Health, 2006. National Cancer Institute: The NCI strategic plan for leading the nation to eliminate the suffering and death due to cancer. Washington DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006. 4. Baron RC, Rimer BK, Coates RJ, et al.: Client-Directed Interventions to Increase Community Access to Breast, Cervical, and Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 2008; 35(1): S56-S66. 13 5. Tufte ER: The visual display of quantitative information, 2nd ed. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press, 2001. 6. Cartwright W, Crampton J, Gartner G, et al.: Geospatial information visualization user interface issues. Cartography and Geographic Information Science 2008; 28(1): 1-19. 7. Glaser SL, Clarke CA, Gomez SL, O'Malley CD, Purdie DM, West DW: Cancer surveillance research: a vital subdiscipline of cancer epidemiology. Cancer Causes and Control 2005; 16(9): 1009-1019. 8. Benz CC, Clarke CA, Moore DHn: Geographic excess of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers Prevention 2003; 12(12): 1523-12527. 9. Clarke C, Glaser S, West D, et al.: Breast cancer incidence and mortality trends in an affluent population. Breast Cancer Research 2002; 4(6): R13. 10. Clarke CA, Glaser SL, Uratsu CS, Selby JV, Kushi LH, Herrinton LJ: Recent declines in hormone therapy utilization and breast cancer incidence: clinical and population-based evidence. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2006; 24(33): 49-50. 11. Clarke CA, Glaser SL: Declines in breast cancer after the WHI: apparent impact of hormone therapy. Cancer Causes and Control 2007; 2007(18): 8. 12. Cockburn M, Swetter SM, Peng D, Keegan TH, Deapen D, Clarke CA: Melanoma underreporting: why does it happen, how big is the problem, and how do we fix it? Journal of the American Academy of Dermatologists 2008; 59(6): 1081-1085. 13. Linos E, Swetter S, Cockburn M, Colditz G, Clarke C: Increasing Burden of Melanoma in the United States. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2009; E-pub ahead of print 14 14. Schootman M, Jeffe D, Lian M, Gillanders W, Aft R: Geographic clustering of adequate diagnostic followup after abnormal screening results for breast cancer among low-income women in Missouri. Annals of Epidemiology 2009; 169: 554-561. 15. Lian M, Jeffe DB, Schootman M: Racial and geographic differences in mammography screening in St. Louis city: A multilevel study. Journal of Urban Health 2008; 85: 677-692. 16. Schootman M, Jeffe D, Gillanders W, Yan Y, Jenkins B, Aft R: Geographic clustering of adequate diagnostic follow-up after abnormal screening results for breast cancer among lowincome women in Missouri. 2007; 17: 704-712. 17. Schootman M, Sterling DA, Struthers J, et al.: Positional accuracy and geographic bias of four methods of geocoding in epidemiologic research. Annals of Epidemiology 2007; 17: 464470. 18. Schootman M, Jeffe D, Kinman E, Higgs G, Jackson-Thompson J: Evaluating the utility and accuracy of a reverse telephone directory to identify the location of survey respondents. Annals of Epidemiology 2005; 15(2): 160-166. 19. Kreuter M, Skinner C, Holt C, et al.: Cultural tailoring for mammography and fruit and vegetable intake among low-income African American women in urban public health centers. Preventive Medicine 2005; 41(1): 53-62. 20. Kreuter M, Buskirk T, Holmes K, et al.: What makes cancer survivor stories work? An empirical study among African American women. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2008; Epub ahead of print. 21. Kreuter M, Green M, Cappella J, et al.: Narrative communication in cancer prevention and control: A framework to guide research and application Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2007; 33(3): 221-235. 15 22. Hinyard L, Kreuter M: Using narrative communication as a tool for health education behavior change: A conceptual, theoretical, and empirical overview. Health Education & Behavior 2007; 34(5): 777-792. 23. Wallack L, Woodruff K, Dorfman L, Diaz I: News for a change: An advocate's guide to working with the media. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, 1999. 24. Thompson V, Cavazos P, Jupka K, Caito N, Gratzke J, Tate K: Evidential preferences: Cultural appropriateness strategies in health communication. Health Education Research 2007; (Epub ahead of print). 25. Caburnay C, Luke D, Cameron G, et al.: The Ozioma News Service: Using customized cancer news releases to increase quantity and quality of cancer coverage in Black newspapers. American Journal of Public Health Under review. 26. Nicholson R, Kreuter M, Lapka C, et al.: Unintended effects of emphasizing disparities in cancer communication to African Americans Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 2008; 17: 2946-2953. 27. Luke D: Getting the big picture in community science: Methods that capture context. In: Menard S, ed. Handbook of Longitudinal Research: Design, Measurement, and Analysis across the Social Sciences: Academic Press, 2005. 28. Harris J, Luke D, Burke R, Mueller N: Seeing the forest and the trees: Using network analysis to develop an organizational blueprint of state tobacco control systems. Social Science & Medicine 2008; 67(1669-1678). 29. Luke D, Harris J: Network analysis in public health: History, methods, and applications Annual Review of Public Health 2007; 28: 69-93. 16 30. Luke D, Esmundo E, Bloom Y: Smoke signs: Patterns of tobacco billboard advertising in a metropolitan region. Tobacco Control 2000; 9: 16-23. 31. Shelton S, Herbers S, Mueller N, Luke DA, Harris J: The Lay of the Land: Mapping Missouri’s Tobacco Control Funding: 2006-2008. Report produced for the Missouri Foundation for Health, 2008. 32. McGuire W: Theoretical foundations of campaigns. In: Rice R, Atkin C, eds. Public Communication Campaigns, 2nd ed. Newbury Park: Sage, 2001; 43-65. 33. Petty R, Cacioppo J: The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 1986; 19: 123-205. 34. Witte K, Allen M: A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education and Behavior 2000; 27: 591-615. 10 Journal Submission ideas: http://iamcr.org/s-wg/mcpc/hco/572-braga-2010-hco-cfp http://associationdatabase.com/aws/CSCA/pt/sp/callforpapers_health http://associationdatabase.com/aws/ECA/pt/sd/news_article/14790/_parent/layout_details/false Journals Journal of Clinical Oncology Information Design Journal of Health and Mass Communication American Journal of Health Behavior American Journal of Health Promotion Cancer 17 Communication Research Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health Journal of the National Cancer Institute Preventing Chronic Disease American Journal of Preventive Medicine Health Literacy Social Science and Medicine Journal of Biomedical Informatics