Paper - ILPC

advertisement

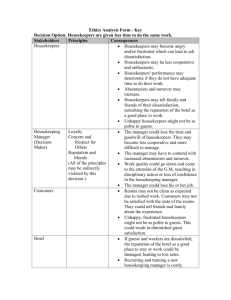

Control effectiveness: servitude or seduction? Roslyn Larkin – University of Newcastle, Australia Abstract As awareness of the value of organisations knowledge stocks increase, methods of leveraging the knowledge for effective transfer with a view to exploitation have become significantly more focused. This paper considers two very different forms of control employed by a Multinational Enterprise (MNE) in an attempt to convince site managers to engage in knowledge transfer through the organisation’s dedicated Information Communication Technology (ICT) system. While both approaches could be considered punitive, they differ significantly through the control that is exerted as a result of the design of the system. That is, the first controls through bureaucratic means while the second through social systems. Analyses of findings demonstrate the power of controlling knowledge sharing behaviours through subtle methods. The primary contribution of the paper is both theoretical and practical through advancement of current understanding of the importance of alternative control mechanisms to leverage quality knowledge outcomes. The research is qualitative using semistructured interviews undertaken with managers across 19 sites of an MNE operating in the Australian hospitality sector. Data was analysed using a multi-tiered coding and thematic analysis techniques consistent with qualitative enquiry. Introduction The knowledge based view identifies the firms heterogeneous knowledge bases as a significant determinant of a firms strategic competitive advantage (SCA). Drawing from this theory, research has made some enlightening contributions as to the characteristics of knowledge, typically reported as explicit or tacit, and individual or collective, and its transfer throughout the firm, typically through mechanisms of Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) or social systems. Indeed it is the transfer or sharing of knowledge throughout global subsidiaries that Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) seek as an avenue to SCA and as a result significant investment has been made in understanding and employing control systems to leverage strategic knowledge from one point in the organisation to others. This paper, grounded in the knowledge based theory is situated within an MNE using HRM as a control mechanism for the leveraging of explicit subsidiary knowledge through the firms ICT system. That is, the paper considers the effects of different control mechanisms on knowledge sharing behaviours. There is a significant stream of literature informing understanding of the role HR plays to control knowledge sharing behaviour. To date such HR practices are situated within top down driven bureaucratic control systems usually directed towards performance management and reward for the knowledge owner and/or gatekeeper. While useful for understanding the relationship between HR practices and knowledge sharing outcomes, however, research so far has largely failed to consider alternative or more subtle control mechanisms such as social control or indirect control mechanisms to elicit knowledge sharing behaviours. It is here therefore that this paper provides benefit to those who design control systems and those who study them by drawing distinction through a comparative case study of one organisations use of two quite different control systems, each through HR practices. Significantly, based on the evidence, the paper proposes that while research has generated some understanding of the effects of direct control methods on knowledge sharing behaviours, such forms of bureaucratic top-down control are sustainable only in so far that they have temporal finite measurement attached to the consequences for the knowledge gatekeeper. Where the consequences of knowledge sharing behaviour affect the gatekeeper indirectly, in this case through a sub-group, the knowledge sharing behaviours of the gatekeeper are moderated through social control or more subtle mechanisms. This paper offers an exploratory investigation into the factors controlling knowledge transfer in one multinational organisation. The primary contribution of the paper is both theoretical and practical through advancement of current understanding of the importance of alternative control mechanisms to leverage quality knowledge outcomes. The paper is structured as follows. First the literature will be reviewed and analysed to identify the predominant research focus to date and key areas requiring further focus. Following will be a comprehensive discussion of the research methodology and its suitability for research of this nature. The next section will profile the cases which will be followed by an analytical discussion of the complexities between the two. The paper will conclude with recognition of the limitations of the research and identification of areas requiring further consideration. Understanding knowledge The knowledge-based view of the firm attributes a firms competitive advantage to its unique knowledge and its ability to embody new knowledge in its products and services (Lippman & Rumelt, 1982; Nonaka, 1991; Conner & Prahalad, 1996; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998; Chakravarthy, McEvily, Doz & Rau, 2006. The management of the knowledge however has been identified as one of the most important challenges facing today’s managers (Drucker, 1993; Simon, 1996; Davenport & Prusak, 1998; van den Hoof and Ridder, 2004). The importance attributed to the value that can be created from knowledge has contributed to a change in attitude of the role of the MNE subsidiary. Previously, and according to a traditional ethnocentric model (Perlmutter 1969), knowledge was viewed as a linear sequence (Almeida & Phene, 2004) created by headquarters and disseminated vertically to the subsidiaries. More recently however the role that the subsidiaries play in the creation of value from knowledge has also evolved (Almeida & Phene, 2004; Birkinshaw & Hood, 2000; Dunning, 1994, Malnight, 1995; Porter, 1990) and while subsidiaries may still exploit organisation wide knowledge, they simultaneously engage in their own knowledge generation or augmentation (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990; March, 1991). Typically, literature on ‘knowledge’ comes under one of two key headings. The first, explicit knowledge relates to knowledge that is codified and easily communicated (Newell et al, 2009; Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997; Zollo and Winter, 2002). It is impersonal in nature and usually takes the forms of documents and reports, presentations or catalogues (Holste & Fields, 2010; Nonaka & Takuechi, 1995; Tsoukas, 2006). The other, tacit knowledge, is developed through experience and its personal nature makes it hard to communicate or be reduced to textual form. It’s hard to measure and unable to be stored using technology (Choo, 2000; Nonaka & Takuechi, 1995). Leveraging and transferring Knowledge The above section leaves little doubt that it is in the best interest of the MNE to exploit the knowledge residing in various parts of the organisation. At this point, two key areas must be considered. The first is leveraging individual knowledge so that it becomes collective and ultimately organisational, meaning that it is applied in another part of the organisation and second the mechanism through which the knowledge is transferred from on part of the organisation to another. Indeed, Kogut & Zander (1993) claim that an MNE arises from its superior efficiency to transfer knowledge across borders. Just as there are differing interpretations regarding the nature of knowledge, there are likewise differing mechanisms for its transfer. The suitability of each mechanism coincides with the nature of the knowledge and whether it is tacit or explicit. For example, when considering the mechanism for the transfer of tacit knowledge, priority is given to social mechanisms. These are commonly referred to as communities (Jones, 1995; Komito, 1998; Von Krogh, 2006; Wenger & Snyder, 2000) or networks (Van Wijk, Van Den Bosch & Volberda, 2006; Newell et al, 2009). When considering the mechanism for the transfer of explicit knowledge, emphasis is on Information Communication Technologies (ICTs) focussing on the transfer of codified knowledge through computerised repositories (Alani & Tiwana, 2006; Zack, 1999). In a complex MNE environment however coordination and control of knowledge sharing behaviour, or, the leveraging and adoption of knowledge from one point in the organisation to another becomes increasingly difficult. This is especially so where knowledge transfer barriers exist. Known barriers (for example, knowledge hoarding (Cyert 1995)) may arise at the point of the knowledge sender, or at the point of the knowledge receiver (for example, stickiness (Szulanski 1996) and Not Invented Here Syndrome (NIH) (Katz & Allen 1982)). As a result, organisations require processes and practices in place to promote knowledge sharing behaviours and overcome the known barriers to its transfer and adoption. Motivation and Control through HRM Within the last ten years, much focus has shifted to the potential of Human Resource Management (HRM) as a series of practices that may work to positively control organisational knowledge transfer. For example, Minbaeva, Pedersen, Bjorkman, Fey and Park (2003) considered the motivational effects of bundles of HR practices on knowledge sharing behaviours, while Lee, Williams & Yin (2006 considered the effect of individual HR practice on behaviours. More specifically is the interest in the link between extrinsic motivators such as performance reviews as a control device to elicit explicit knowledge sharing behaviour (Edvardsson 2007), through ICT systems. Indeed although the strength of the outcomes have been somewhat moderated (for example Gagne 2009) this area has been afforded much attention. The link between performance management and knowledge sharing behaviours through ICTs however identifies a form of bureaucratic control (Ferner 2000). Indeed, while some consideration has been provided to social control mechanisms these have been considered predominately through the development of social capital (Welch et al, 2009; Bontis & Fitz-enz 2005, Nahapiet & Ghoshal 1998), and social transfer mechanisms. At no point therefore, has social control been investigated as a mechanism for the control of knowledge transfer through ICT systems, which until now has been the domain of bureaucratic control systems. It is here therefore that this paper departs from the mainstream and considers the effect of social control mechanisms on the transfer of explicit knowledge through ICTs through comparison of two case examples, one using bureaucratic control through the organisations performance management system and the other through social control at the workplace level. This research is undertaken at the subsidiary level of an MNE operating in the International Hospitality environment Methodology Design This research is qualitative and uses a complex case study approach. Qualitative research was selected as the purpose is to understand the decisions of the actors when they have rational alternatives (Gardner 1999: 60). Therefore, the research is built on constructivist perspectives where knowledge and reality is contingent upon interaction between human beings and their world in a social context where meaningful reality is socially constructed (Crotty 1998). Further, qualitative research occurs in natural settings where the researcher attempts to bring meaning to phenomena in a world that is already there. That is, it’s a situated activity (Denzin & Lincoln 2005), interested in studying how people attach meaning to their lives and uncover perceptions and experiences of informers (Minichiello, Aroni, Timewell & Alexander 1995). Qualitative research can be used when the research is exploratory in nature and is useful when there is little understanding regarding a phenomena (Collis & Hussey 2003; Cresswell 2003). A case study was chosen as the purpose is to understand the phenomenon in depth and within its natural context (Punch 1998). In this case is not the purpose of the research to provide generalisations but to consider causal factors rather than frequencies (Mitchell 1989; Denzin 1989; Stake 2000). That is, reliability relies upon the cogency of the theoretical reasoning rather than on the typicality of the case (Connell, Waring & Lynch 2000). Further the case was chosen not as a result of its ordinariness but rather because of its interest (Stake 2000). Data Collection Emencorp, the case study organisation, was considered suitable for this research as its people management is best described as geocentric. That is, it is harmonized in such a way that it is managed on a global basis while at the same time responding to local environment factors (Watson & Littlejohn 1992). In this way, the research was able to pick up both centralised and local programs. Data collection occurred between 2008 and 2009 through semi-structured interviews. Overall, 19 managers (7 regional and 12 site managers) across 19 hotel sites in 3 Australian states provide input into these outcomes. Each interview had an approximate duration of 1-1.5 hours. The following table provides an example of the predominant themes of the interview questions with examples. Theme Purpose The organisation’s perspective on knowledge transfer This theme provided a useful starting point to gauge mangers views on the organisation’s commitment to knowledge sharing. The responses provided a point of comparison to relevant organisational documents to establish what was viewed as rhetoric and reality. It also provided early insight into the systems in place. This theme enabled the researcher to learn about the knowledge transfer mechanisms from the perspective of the managers. It also helped to identify the number of systems in place either from a formal or informal perspective. This was achieved as different employment positions use different systems for communication. In addition, it enabled The employee’s experience with the knowledge transfer mechanisms Questions - example Do you believe the organisation has a commitment to sharing knowledge throughout its global network? Why?/Why not? Does the organisation have mechanisms in place to support knowledge transfer? 1) ICT 2) Social systems Tell me about your experiences with knowledge sharing through ICT mechanisms. Tell me about your experiences with knowledge sharing through social mechanisms. Are there any other mechanisms for sharing knowledge that you haven’t covered in your discussion? HR practices and knowledge transfer discussion about organisational changes overtime, and helped to differentiate between the attitudes and experiences of long serving employees and those newer to the organisation. This theme helped to identify HR practices that the employee personally considered as useful to knowledge transfer. Additionally, it assisted the process of triangulation in that it enabled the researcher to delve deeper into the practices that were articulated as identifying with knowledge transfer in documentary data and their actual application. Which, if any, HR practices do you consider to influence the quality of the KT mechanisms you have identified? I note that in the documents providing the procedures for performance appraisal, HR staff are prompted to identify with knowledge sharing activities. Do you do this? Does your manager include this dimension when conducting your performance review? Data Analysis Consistent with qualitative research the analytical categories were emergent throughout data collection and as such informed early analysis. In order to manage such large amounts of unstructured data, Nvivo 8 was used to assist a 3 layer coding technique. Initially, a process of data reduction was undertaken where individual elements were organised into concepts and categories. The next stage considered the interconnectedness of data taking into consideration the context in which it was embedded, the way it was managed and the consequences of such. Finally, selective coding was undertaken in order to validate relationships. Throughout analysis several iterations of relationships occurred as additional categories were considered and whereby areas of overlap and antecedents emerged. Background to the cases Case Commonalities In 2006, Emencorp implemented a vast storage and retrieval knowledge system referred to from here on as the knowledge library. Established in line with the organisations strategic focus of global alignment, the knowledge library was to facilitate sharing of value added processes and practices across sites thus reducing time and resource waste and replication. In other words its purpose was to initiate a long term knowledge sharing culture. At the time of data collection, the knowledge library extended across all 140 hotels in the Asia, Australasian global region. The knowledge library acts as a two-way system allowing users to both submit and retrieve ideas. Indeed, the viability of the system relies on both, new knowledge sharing and the implementation of the new knowledge across sites. The ideas are stored by hotel function (i.e. food and beverage; housekeeping etc). Initially, access to the system was limited to site managers and above however this was eventually relaxed so that all staff from a supervisory level up can access the data. Submission of ideas continues to be limited to site managers and above as part of the gatekeeping function. The following cases identify control mechanisms employed by Emencorp to promote system use.. Case 1 – The knowledge library and the site managers (1) In order to create a culture of knowledge sharing behaviour through the ICT system, each hotel or site manager was notified by their regional managers that the knowledge library was now in place and there was an expectation that each site manager would conform to its use. In order to support this conformity, use of the knowledge library was linked directly to each site managers Key Performance Objectives (KPOs). Measurement of the KPOs involved each site manager retrieving and implementing two ideas from the library each year into their hotel and each manager should add two ideas to the library each year for others to view and potentially implement in their hotels. Achievement of the KPOs was assessed through the site managers annual performance review. The link with the performance management system however was to be relatively short lived. By 2008, just two years after its beginning the link with site managers KPOs were disestablished. From a managerial perspective the reason for removing the link was recognition of the constraints of site managers to continually put forward quality ideas. This is captured in the following quote from a regional manager, There were a lot of things that ended up there because people were pressured to contribute and you cannot always contribute quality (RSM2). Evidence from the site managers, while supporting this general theme however were a little more insightful. For example, I wasn’t a big fan of the link with KPOs because you would get to mid-November and you felt: Oh gosh, I haven’t added two ideas so you would get on the Knowledge Library and it was potentially a gun pointed at your head (GSM3). In addition to the forced compliance, a further theme began to emerge, We were mandated through our KPOs so would that influence me to share? Yes, it would, but it turned into a dog’s breakfast, everyone’s throwing in ideas just to tick the box. I think they dropped it because it discredited the system. It’s better to have 10 ideas rather than 100 if 90 aren’t good. That’s not the official reason, but unofficially I think that’s it (GSM3). Another respondent more candidly hinted at sabotage, The link with KPOs might have influenced me to share, but would it be good data going into it? We proved it wouldn’t so they had to scrap it and start again [be]cause they were silly ideas and now it’s no longer linked to our KPOs (GSM6). The separation of the Knowledge Library and site managers KPOs opened the system up to wider access. It was at this time that those in a supervisory or above position were granted access to view ideas generated from other properties although access to add an idea remained with the site manager. By all accounts however, the Knowledge Library lapsed into either underuse or in many cases disuse. Almost paradoxically, the site managers blamed the severed link with their KPOs as the reason for this. For example, There’s probably a lot of good ideas there…but if it’s not part of your KPOs then it’s not something you think about (GSM7). Case 2 – The knowledge library and the housekeepers (and the site managers) Typically, Emencorp exhibit a geocentric form (REF). In this case, this is identified through the centralised approach to strategic HRM operating simultaneously with the decentralisation of many operational HR decisions to the regional, national or in the case of Australia, state level. As such, varying operational models exist amongst the Australian sites. One such variance was the employment of housekeeping staff in some states and the outsourcing of the housekeeping function and staffing in others. This divergence of staffing practices has triggered much debate regarding the overall utility of the mixed model. In 2009, the debate led one RGM to implement a project entitled the ‘housekeepers project’ in order to establish whether there are cost and operational advantages to staffing the function rather than outsourcing it. The basic premise of ‘housekeepers project’ was identified as follows: If we outsource, what we are saying is ABC outsourcing has a better culture than Emencorp. By outsourcing you are saying that management doesn’t understand how to manage something… so I said to Norman [pseudonym] let’s get the housekeepers together and see if we can develop best practice or else we can outsource it…you see there appears to be a mentality of if you can’t measure it you can’t manage it… so I gave the housekeepers something that was pretty measureable, that’s called job security (RGM2). The project involved the following steps. First, all executive housekeepers in the state are brought together to a central location each month in order to discuss potential projects or areas requiring improvement, new ideas they are considering and, updates on process improvements or projects they are currently working on. Teams of 2 or 3 executive housekeepers are formed and each team becomes responsible for developing, trialling and reporting each separate project. If the trial is successful and the idea is considered to produce efficiencies it is deemed a ‘best practice’ initiative and added to the knowledge library. In other words, in this case, quality and innovation are inherent in the design of the initiative. The final stage and where ultimate measurement of success of the house keeper’s project occurs however is at the hotel level. That is, if it is not picked up and implemented in hotels then it is deemed to be a failure which by implication extends to the housekeepers project generally and ultimately employment of the housekeepers. Therefore, as it is clearly in the interests of the housekeepers to have the best practice initiatives implemented at their hotels, it is up to them to convince the site managers to undertake the processes (practical and administrative) of implementation. This is captured in the following quote: It’s no longer up to the attitude of the site manager, it was the degree of engagement by the housekeepers that was an interesting learning curve and, the pressure created by the time we got half way into it. You recognise and reward the people who are doing a good job, so the peer group put pressure on those site managers with NIH…until they realised it was about getting a result… (RGM2) Although the Housekeepers project was still quite ‘new’ at the time of data collection, discussion with the regional manager responsible for its implementation deemed it an early success. That is, as a result of pressure exerted by executive housekeepers, site managers were adopting the knowledge sharing culture through implementation of the best practice ideas that were being placed in the knowledge library. Analysis and discussion Each of the two examples above identify with the full knowledge transfer process of sending, receiving and implementing new knowledge channelled through the organisations dedicated ICT system. Structural similarities between the two include the use of punitive outcomes relating to job security (although disproportionately) for non-compliance and that each was operationalised through HR practices. Also, although again disproportionate in relative strength, both examples identify with a reduction in known transfer barriers such as NIH and negative attitudes towards sharing. Finally, common to both cases is an onus on the site managers for accessing the data and implementing new knowledge. Key differences between the cases however require further consideration and appear to reside within two main categories. These are the nature of the control mechanism that accomplishes the actual transfer, and, the knowledge sharing outcome as a response to the mechanism. The following table provides a snapshot of the content of differences and each of these is discussed in further detail below. Responsibility Affect Control Measure Pressure Innovation Outcome HR practice Response Performance Management system Site Managers Direct Bureaucratic Quantitative Top-down Low Short term (tick-the-box) Performance appraisal Individual Housekeepers project Housekeeping staff Indirect Social Qualitative Bottom-up High Long term (culture) Outsourcing Collective Control Mechanism As mentioned above a commonality between the cases was that lack of conformity resulted in some form of punitive outcome. Structurally however, the requirement differed in terms of the party held responsible for the outcome and the method by which the outcome was achieved. For example, in the first case, knowledge transfer outcomes were achieved through direct or overt control where the site manager was required to become subservient to management through bureaucratic methods. In the second case, however, control was achieved indirectly or possibly covertly, filtered through the social mechanisms existing between the housekeepers and the site managers at the level of the hotel. Predominately, the location of the value of the knowledge shifted from site managers to housekeepers pressuring the housekeepers to modify the knowledge transfer behaviours of the site managers which resulted in knowledge transfer outcomes achieved as a result of persuasion rather than subjection. Knowledge sharing outcomes The second area that differed significantly between the examples is within the characteristics or quality of the actual knowledge transfer outcome as a response to the control mechanism. For example, the first case demonstrated that controlling through bureaucratic quantitative assessment while achieving accountable measures may produce a series of unanticipated and unwelcome outcomes towards both the knowledge library and longer term knowledge sharing culture generally. First, there was a distinct air of resentment towards the link with the project management system from the site managers. This was clearly captured in the comment ‘…it was potentially a gun pointed at your head…’ (GSM3). Further, the design resulted in creating a negative or at best a null response to the utility of the knowledge library from the site managers where it became viewed as a means to an end or a vehicle through which to ‘tick the box’ resulting in short term conformity rather than a longer term commitment to knowledge sharing. These outcomes were far removed from the original intention of the system where its implementation was to facilitate a knowledge sharing culture. Further, the ideology of the system was to share value added or innovative processes and practices in order to gain efficiencies. With only a quantitative measurement attached to the link with the performance management control system, site managers by admission shared ‘silly ideas’ ultimately turning the knowledge library into a ‘dogs breakfast’. On the other hand, innovation and quality was part of the inherent design of best practice and therefore, by extension, became an object of the implementation. Conclusion and limitations The above examples identify one organisations experience shifting from a direct bureaucratic control mechanism to indirect control through social mechanisms in order to elicit knowledge sharing behaviour from their site managers. This shift took place when the knowledge sharing system lapsed into disuse as a result of unintended consequences of the bureaucratically controlled mechanism. By shifting and adding to the personal value of the knowledge exchange from site managers to housekeepers, the organisation was able to indirectly control site managers by creating an environment of persuasion dispensed through the social system. This was in stark contrast to the previous bureaucratic system built on direct obedience. Additionally, while each control mechanism delivered a knowledge sharing response, the indirect method proved most productive for quality of knowledge and appropriate use of the knowledge sharing system. In a practical sense this signals a caution for managers to not only consider the potential outcomes of their control systems but to ensure that the design of the control system provides a desired outcome. That is, by definition, quality over quantity and pull rather than push. From an academic perspective, this paper offers a small increment to better understanding social control systems in MNEs but is not without limitations. Significantly, as the housekeepers project was in its infancy at the time of data collection, the results were unable to be further tested and therefore more work in this area is needed. Related areas include whether without the duress of control as an explanatory logic for use, the Knowledge Library, under the housekeepers project instils an actual long term knowledge sharing culture and will become embedded in the organisational routines. One may argue that a considerable limitation to this outcome is that housekeepers did not participate directly in this research. However, while that would make an interesting inclusion in further research it was not the purpose of this paper. Rather, the paper is about the control mechanisms the organisation uses to promote knowledge sharing through the ICT system. Finally, multi-disciplinary research might go some way to assist in uncovering the raison d’etre for the shift. For example was it created as a result of collective action, or was it a sense of responsibility from the site manager for the housekeeping staff? Further, was it a sense of guilt? Either way, it is clear that this form of indirect control applies pressure from below to achieve organisational outcomes in a way that promotes quality knowledge transfer outcomes. Reference List Almeida, P., & Phene, A. (2004). Subsidiaries and Knowledge Creation: The Influence of the MNC and Host Country on Innovation. Strategic Management Journal, 25, pp.847-864. Argote, L., & Ingram, P. (2000) Knowledge Transfer: A Basis for Competitive Advantage in Firms. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 150169. Birkinshaw, J., & Hood, N. (2000). Characteristics of foreign subsidiaries in industry clusters. Journal of International Business Studies, 31(1), 141-154. Chakravarthy, B., McEvily, S., Doz, Y., & Rau, D. (2006). Knowledge Management and Competitive Advantage. In M. Easterby-Smith, & M. Lyles, (Eds) (pp.305-324). The Blackwell handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management, Blackwell: Oxford. Conner, K., & Prahalad, C. (1996). A Resource-based Theory of the Firm: Knowledge versus Opportunism. Organization Science, 7(5), 477-501. Cohen, W., & Levinthal, D. (1990). Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128-149. Coyne, R. (1997). Language, space, and information. In P. Droege, (Ed), Intelligent Environments. Elsevier: Amsterdam. Davenport, T., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge: How organizations manage what they know. Harvard Business School Press: Boston. Davis, J., Subrahmanian, E., & Westerberg, A. (2005). The “global” and the “local” in knowledge management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 9(1), 101-112. Drucker, P. (1993). Post-Capitalist Society, Oxford: Butterworth, Heinemann. Dunning, J. (1994). Multinational enterprises and the globalization of innovatory capacity. Research Policy, 23, 67-89. Hansen, M., Nohria, N., & Tierney, T. (1999). What’s Your Strategy for Managing Knowledge?. Harvard Business Review, March-April, 105-116. Hayes, N., & Walsham, G. (2006). Knowledge Sharing and ICTS: A Relational Perspective. In M. Easterby-Smith, & M. Lyles, (Eds) (pp. 54-78). The Blackwell handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management, Blackwell: Oxford. Kogut, B., & Zander, U. (1992). Knowledge of the Firm, combinative Capabilities, and the Replication of technology. Organization Science, 3, 383-397. Komito, L. (1998). The Net as a Foraging Society: Flexible communities. The Information Society, 14, 97-106. Lee, D., & Allen, T. (1982). Integrating new technical staff: Implications for acquiring new technology. Management Science, 28, 1405-1420. Malnight, T. (1996). The transition from decentralized to network-based MNC structures: an evolutionary perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(1), 4356. Minbaeva, D,. Makela, K. & Rabbiosa, L. (2012) ‘Linking HRM and knowledge transfer via individual-level mechanisms’, Human Resource Management, May/ June, 51(3), pp.387-405 Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital and the Organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242-266. Newell, S., Robertson, M., Scarbrough, H., & Swan, J. (2009). Managing Knowledge Work and Innovation, 2nd Ed. Palgrave Macmillan: UK. Nohria, N., & Ghoshal, S. (1997). The Differentiated Network: Organizing Multinational Corporations for Value Creation. Jossey-Bass: San Fransisco. Perlmutter, H. (1969). The Tortuous Evolution of the Multinational Corporation. Columbia Journal of World Business, January-February, 9-36. Porter, M. (1990). The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Free Press: New York. Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches, SAGE: London & Thousand Oaks. Spender, J. (1996). Organizational knowledge, learning and memory: three concepts in search of a theory. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 9(1), 63-78. Szulanski, G. (1996). Exploring Internal Stickiness: Impediments to the Transfer of Best Practice Within the Firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17, Special Issue, 27-43. Van den Hooff, B., & Ridder, J (2004). Knowledge sharing in context: The influence of organizational commitment, communication climate, and CMC use on knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 8(6), 117 – 130. Van Wijk, R., Van Den Bosch, F., & Volberda, H. (2006). Knowledge and Networks. In M. Easterby-Smith, & M. Lyles, (Eds) (pp. 428-454). The Blackwell handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management, Blackwell: Oxford. Von Krogh, G. (2006). Knowledge Sharing and the Communal Resource. In M. EasterbySmith, & M. Lyles, (Eds) (pp. 372-393). The Blackwell handbook of Organizational Learning and Knowledge Management, Blackwell: Oxford. Zack, M. (1999). Managing Codified Knowledge. Sloan Management Review, 40(4), 45-58.