Finance 510: Microeconomic Analysis

advertisement

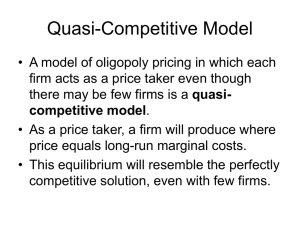

Finance 510: Microeconomic Analysis Anti-Competitive Behavior Market Dominance Campbell’s Soup has accounted for 60% of the canned soup market for over 50 years Sotheby’s and Christie’s have controlled 90% of the auction market for two decades (each holds 50% of its own domestic market) Intel has held 90% of the computer chip market for 10 years. Microsoft has held 90% of the operating system market over the last 10 years On average, the number one firm in an industry retains that rank for 17 – 28 years! Entry/Exit and Profitability Bananas p p Apples S S D’ D D’ q D q Its normally assumed that as demand patterns shift, resources are moved across sectors – as the price of bananas rises relative to apples, there is exit in the apple industry and entry in the banana industry (bananas are more profitable) THIS IS INCONSISTANT WITH THE FACTS!! Evolving Market Structures….Some Facts Entry is common: Entry rates for industries in the US between 1963 – 1982 averaged 8-10% per year. Entry occurs on a small scale: Entrants for industries in the US between 1963 – 1982 averaged 14% of the industry. Survival Rates are Low: 61% of entrants will exit within 5 years. 79.6% exit within 10 years. Entry is highly correlated with exit across industries: Industries with high entry rates also have high exit rates Entry/Exit Rates vary considerably across industries: Clothing and Furniture have high entry/exit, chemical and petroleum have low entry/exit. The data suggests that most industries are like revolving doors – there is always a steady supply of new entrants trying to survive. Entrants Market Dominated by Incumbents Exits The key source of variation across industries is the rate of entry (which controls the rate of exit) Is this a result of predatory practices by the incumbents? Predatory Pricing vs. Profit Maximizing Remember, firms are also profit maximizing. Specifically, they are always looking for ways to minimize costs p MC (Short Run) P P’ MC (Long Run) D Q Q’ q MR Predatory pricing describes actions that are profitable only if they drive out rivals or discourage potential rivals! Limit Pricing Consider the Stackelberg leadership example. Firm one chooses its output first. This leaves Firm two the residual demand. Also, assume that there is a fixed cost of production (F) p D2 ( P) D( P) qˆ1 P̂ Market Demand D(P) q̂1 q Firm One’s output choice Limit Pricing Consider the Stackelberg leadership example. Firm one chooses its output first. This leaves Firm two the residual demand. Also, assume that there is a fixed cost of production (F) p If Firm 2 chooses to enter, it will maximize profits by choosing q2 P̂ ~ P ~ ( P MC )q2 F MC D(P) q q2 Negative profits for the entrant will deter entry. MR Can Firm one commit to its entry deterring production level? Using capacity choice as a commitment device Recall, that the problem with threatening potential entrants is that the threat needs to be credible (Remember the chain store paradox). One way around this is to “tie your hands” in advance by choice of production capacity. Lets again use a modified version of the Stackelberg leadership game Two firms- an incumbent and a potential entrant facing a downward sloping market demand Both firms have a fixed cost of production One the fixed cost has been paid, production requires one unit of labor (at price w) and one unit of capacity (at price r) Extensive form of the game Stage 1: Incumbent chooses capacity k1 This capacity can be increased later, but not decreased Stage 2: Entrant makes entry decision No Entry: Incumbent remains a monopoly OR Entry: Incumbent and Entrant play cournot (Choosing production levels) Capacity and Marginal Cost mc w r w q mc k1 w r q In period two, the initial capacity choice for the incumbent is now a fixed cost. Therefore, the incumbent has a cost advantage as long as it stays within its initial capacity choice Best Responses As in the initial Cournot analysis, we can derive Firm two’s best response to firm 1 However, with the fixed cost, firm 2 must produce at a minimum scale to earn positive profits q2 Positive Profits Firm 2’s “break even point” q~2 Negative Profits Firm 2 q1 Best Responses Firm 1’s response function has a “kink” at its initial capacity constraint. q2 Given an initial capacity choice by firm 1, this would be the Nash equilibrium in stage two q~2 k1 Firm 2 q1 Nash Equilibrium with entry deterrence q2 To deter entry, Firm one has to choose its initial capacity such that: Firm 2’s best response will be its break even point (with profits equal to zero) Firm one is operating at its initial capacity chosen in period 1. q~2 k1 Firm 2 q1 Capacity as a Predatory Practice In 1945, the US Court of Appeals ruled that Alcoa was guilty of anti-competitive behavior. The case was predicated on the view that Alcoa had expanded capacity solely to keep out competition – Alcoa had expanded capacity eightfold from 1912 – 1934!! In the 1970’s Safeway increased the number of stores in the Edmonton area from 25 to 34 in an effort to drive out new chains entering the area (It did work…the competition fell from 21 stores to 10) In the 1970’s, there were 7 major firms in the titanium dioxide market (A whitener used in paint and plastics). Dupont held 34% of the market but had a proprietary production technique that generated less pollution. When stricter pollution controls were imposed, Dupont increased its market share to 60% while the rest of the industry stagnated. There have been numerous cases involving predatory pricing throughout history. Standard Oil American Sugar Refining Company Mogul Steamship Company Wall Mart AT&T Toyota American Airlines There are two good reasons why we would most likely not see predatory pricing in practice 1. It is difficult to make a credible threat (Remember the Chain Store Paradox)! 2. A merger is generally a dominant strategy!! Predation vs. Merger Again, lets use the Stackelberg Leadership model from before. Two firms (incumbent and entrant) – both with marginal cost (c). They face the market demand curve P A BQ We have already shown the following qA A A c 2B 2 A c 8B A 3c P Ac qB 4B 4 A 2 A c 16 B As a monopoly, Firm A would earn higher profits: M 2 A c 4B The predatory pricing strategy would be to charge a price equal to marginal cost today (earn zero profits) to prohibit entry and then act as a monopolist tomorrow Tomorrow Today 2 A c 0 4B Average 2 A c 8B At the very least, you could offer to merge with the entrant and split the profits 50/50 Today Tomorrow A c 2 8B 2 A c 8B Average 2 A c 8B The Bottom Line… There have been numerous cases over the years alleging predatory pricing. However, from a practical standpoint we need to ask three questions: 1. Can predatory pricing be a rational strategy? 2. Can we distinguish predatory pricing from competitive pricing? 3. If we find evidence for predatory pricing, what do we do about it? Price Fixing and Collusion Prior to 1993, the record fine in the United States for price fixing was $2M. Recently, that record has been shattered! Defendant Product Year Fine F. Hoffman-Laroche Vitamins 1999 $500M BASF Vitamins 1999 $225M SGL Carbon Graphite Electrodes 1999 $135M UCAR International Graphite Electrodes 1998 $110M Archer Daniels Midland Lysine & Citric Acid 1997 $100M Haarman & Reimer Citric Acid 1997 $50 HeereMac Marine Construction 1998 $M49 In other words…Cartels happen! Antitrust Criminal Division Fines ($ Millions) 1000 900 800 700 600 500 400 300 200 100 0 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Cartel Formation In a previous example, we had three firms, each with a marginal cost of $20 facing a market demand equal to P 120 20Q If we assume that these firms engage in Cournot competition, then we can calculate price, quantities, and profits q 1.25M Firm Output Q 3q 3.75 P $45 $31 Industry Output Market Price Firm Profits Total industry profit is $93 Cartel Formation In a previous example, we had three firms, each with a marginal cost of $20 facing a market demand equal to P 120 20Q If these three firms can coordinate their actions, they could collectively act as a monopolist Qm 2.5M q Q / 3 .83M P $70 m $125 Splitting the profits equally gives each firm profits of $41.67!! Cartel Formation While it is clearly in each firm’s best interest to join the cartel, there are a couple problems: With the high monopoly markup, each firm has the incentive to cheat and overproduce. If every firm cheats, the price falls and the cartel breaks down Cartels are generally illegal which makes enforcement difficult! Note that as the number of cartel members increases the benefits increase, but more members makes enforcement even more difficult! Cartels - The Prisoner’s Dilemma The problem facing the cartel members is a perfect example of the prisoner’s dilemma ! Clyde Cooperate Jake Cheat Cooperate $20 $20 $10 $40 Cheat $40 $15 $15 $10 But we know that cartels do happen!! We can assume that carte members are interacting repeatedly over time Cartel agreement made at time zero. 0 1 Play Cournot Game Play Cournot Game Time 2 Play Cournot Game 3 Play Cournot Game 4 Play Cournot Game 5 Play Cournot Game Cartel members might cooperate now to avoid being punished later However, we’ve already shown that if there is a well defined endpoint in which the game ends, then the collusive strategy breaks down (threats are not credible) Multiple Nash Equilibria can allow collusion to happen Acme What is the Nash Equilibrium in this game? Allied $105 The existence of multiple equilibria allow for the possibility of credible threats (and, hence, collusion) $130 $160 $105 $130 $160 $7.32 $7.32 $7.25 $8.25 $5.53 $9.38 $8.25 $7.25 $8.50 $8.50 $7.15 $10 $9.38 $5.53 $10 $7.15 $9.10 $9.10 Multiple Nash Equilibria can allow collusion to happen Acme As in the previous case, a price of $160 can’t be enforced in the last period of play, which causes things to unravel “We both charge $160 until the last period. That period we will both charge $130. If you cheat, I will punish you by charging $105. Allied Consider this strategy: $105 $130 $160 $105 $130 $160 $7.32 $7.32 $7.25 $8.25 $5.53 $9.38 $8.25 $7.25 $8.50 $8.50 $7.15 $10 $9.38 $5.53 $10 $7.15 $9.10 $9.10 Two Period Example Acme Period 2: Is charging a price equal to $130 optimal for both firms? Yes…it’s a Nash equilibrium! Yes! If you charge $130 today, you will be punished with $105 tomorrow – it’s a credible threat because ($105, $105) is a Nash Equilibrium! Allied Period 1: Is charging a price equal to $160 optimal for both firms? $105 $130 $160 $105 $130 $160 $7.32 $7.32 $7.25 $8.25 $5.53 $9.38 $8.25 $7.25 $8.50 $8.50 $7.15 $10 $9.38 $5.53 $10 $7.15 $9.10 $9.10 $9.10 $8.50 $17.60 $10 $7.32 $17.32 (Cooperation) (Cheating) Cooperation also occurs with an infinite horizon (i.e. the game never ends!!) Cartel agreement made at time zero. 0 1 Play Cournot Game Play Cournot Game Time 2 Play Cournot Game 3 Play Cournot Game 4 Play Cournot Game 5 Play Cournot Game Firms will cooperate when its in their best interest to do so! PDV (Cooperation) PDV (Cheating ) Cartels are easier to maintain when there are higher annual profits and interest rates are low! Where is collusion most likely to occur? The central problem with a cartel is as follows: A B cartel Combined profits under the cartel are greater than the non-cooperative situation However, its possible that cartel A 2 or cartel B 2 Member firms might be able to earn more in the non-competitive case than they would in the cartel Cartels require coordination to be maintained…this can be difficult! Where is collusion most likely to occur? High profit potential The more profitable a cartel is, the more likely it is to be maintained Inelastic Demand (Few close substitutes, Necessities) Cartel members control most of the market Entry Restrictions (Natural or Artificial) Its common to see trade associations form as a way of keeping out competition (Florida Oranges, Got Milk!, etc) April 15,1996 (“Grape Nut Monday”): Post Cereal, the third largest ready-to-eat cereal manufacturer announced a 20% cut in its cereal prices Kellogg’s eventually cut their prices as well (after their market share fell from 35% to 32%) The breakfast cereal industry had been a stable oligopoly for years….what happened? Supermarket generic cereals created a more competitive pricing atmosphere Changing consumer breakfast habits (bagels, muffins, etc) Where is collusion most likely to occur? Low cooperation costs If it is relatively easy for member firms to coordinate their actions, the more likely it is to be maintained Small Number of Firms with a high degree of market concentration Similar production costs Little product differentiation Some cartels might require explicit side payments among member firms. This is difficult to do when cartels are illegal! Where is collusion most likely to occur? Low Enforcement Costs If it is relatively easy for member firms to monitor and enforce cartel restrictions their the cartel is more likely to be maintained Example Suppose that you and your fellow cartel members have plants/customers located around the country. How should you set your price schedules? Suppose you have factories in Chicago and Detroit while your chief competitor has plants in Pittsburgh and Baltimore Your customers are located in Cleveland, Dallas, and Atlanta Mill Pricing (Free on Board) A common “mill price” is set for everyone. Then, each customer pays additional shipping costs. Basing Point Pricing A common “basing point” is chosen. Then, each customer pays factory price plus delivery price from the basing point. Advantages of Basing Point Pricing Customers in each location are quoted the same price from all producers. With FOB pricing, mill price is the strategic variable (i.e. a price cut affects all consumers) while with basing point pricing, each consumer location is a strategic variable. This makes retaliatory threats more credible. Price Matching Acme Allied High Price Low Price High Price $12 $12 $5 $14 Low Price $14 $6 $6 $5 Price Matching Removes the off-diagonal possibilities. This allows (High Price, High Price) to be an equilibrium!! Detecting Collusion In general, it is difficult to distinguish cartel behavior from regular competitive behavior (remember, the government does not know each firm’s costs, the nature of demand, etc) Signs of Potential Collusion Phantom Bids (collusive bidding shows lower variance than non-collusive) Little relationship between bids and costs Little relationship between bids and information sets Excess Capacity (as a means of retaliation)