sonnets

advertisement

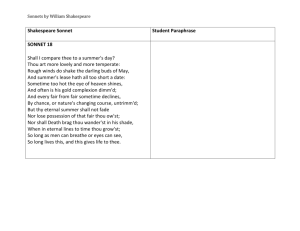

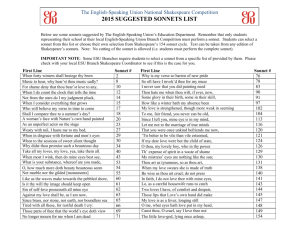

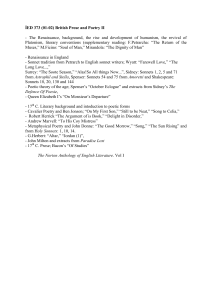

What's a sonnet? A 14-line lyric poem, usually in iambic pentameter in English, with several different rhyme schemes: •Petrarchan: abba abba cde cde (octave + sestet) (a) Wyatt adds a couplet: abba abba cddc ee (b) Donne: abba abba cdcd ee •Shakespearean (Surrey, Drayton): abab cdcd efef gg (three quatrains + couplet) •Sidney: abab abab cdcd ee •Spenser (most difficult): abab bcbc cdcd ee OK, what’s “iambic pentameter”? A ten-syllable (or five “foot”) line whose rhythm alternates unstressed and stressed syllables (or iambs): ˘ / ˘ / ˘ / ˘ / ˘ / The kind of sonnet form that Shakespeare wrote Note that “Shakespeare” is not a natural iamb (neither is “iamb”), but a trochee (stressed-unstressed) that, once inserted into the line, reads iambically. Note also that not every line of every sonnet is perfectly iambic—that would result in an annoying singsong quality. An overall iambic rhythm collides with the natural rhythm of speech to produce the individual sonnet’s particular measure. OK, what’s a “foot”? iambic foot / iamb unstressed + stressed ˘ ́ stressed + unstressed ́˘ unite, repeat, insist, delight trochaic foot / trochee unit, reaper, instant, mother anapestic foot / anapest two unstressed + stressed ˘˘ ́ introduce, disarranged, Brigadoon dactylic foot / dactyl stressed + two unstressed Washington, happiness, syllable spondaic foot / spondee stressed + stressed heartbreak, headline, childhood ́ ́ ́˘ ˘ OK, what’s “iambic pentameter”? A ten-syllable (or five “foot”) line whose rhythm alternates unstressed and stressed syllables (or iambs): ˘ / ˘ / ˘ / ˘ / ˘ / The kind of sonnet form that Shakespeare wrote Note that “Shakespeare” is not a natural iamb (neither is “iamb”), but a trochee (stressed-unstressed) that, once inserted into the line, reads iambically. Note also that not every line of every sonnet is perfectly iambic—that would result in an annoying singsong quality. An overall iambic rhythm collides with the natural rhythm of speech to produce the individual sonnet’s particular measure. The Petrarchan [Francis Petrarch, 1304-1374] sonnet sequence is a series of sonnets (with songs interspersed) exploring the contrary states of feeling a lover experiences as he desires and idolizes an unattainable lady: some conventional themes concern the lady's great beauty [blazon or inventory conceit], her power over him, her cruelty to him, his sleeplessness, the fire of his love and the ice of her chastity, the pain of absence, the renunciation of love, the eternity and originality of his poems. English sonneteers include: 1. Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-42) who brought the form to England; he and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1517-47) represent the first generation; afterwards come (all born after the death of these two) 2. Edmund Spenser (Amoretti); George Gascoigne; Sir Philip Sidney (Astrophil and Stella); Samuel Daniel (Delia); Shakespeare; Michael Drayton (Idea); John Donne (Holy Sonnets); Sir John Davies (Gulling Sonnets); Fulke Greville (Caelica); Lady Mary Wroth (Pamphilia to Amphilanthus) ["all-loving" to "lover of two"] Some sonnet conventions: 1. The blazon, or inventory of beauties. Embraced by Spenser, Amoretti 15; parodied by Shakespeare, # 130. 2. the power of poetry: Spenser 75 (name on the strand), Shakespeare 18 (summer's day), 19, 55 3. the power of the beloved: Sidney 41 (success in arms), 74 (success in verse due to kiss); Shakespeare 29 (when in disgrace) 4. naturalness, artlessness of verse: Sidney 1 (note hexameters), 74 5. reason versus passion, divine versus earthly: Sidney 5, 52, 71; Spenser 68, 79 6. the feigned renunciation of love: Drayton 61 Blazon and Anti-blazon YE tradefull Merchants that with weary toyle, do seeke most precious things to make your gain: and both the Indias of their treasures spoile, what needeth you to seeke so farre in vaine? For lo my love doth in her selfe containe all this worlds riches that may farre be found; if Saphyres, lo her eyes be Saphyres plaine, if Rubies, lo hir lips be Rubies found; If Pearles, hir teeth be pearles both pure and round; if Yvorie, her forhead yvory weene; if Gold, her locks are finest gold on ground; if silver, her faire hands are silver sheene, But that which fairest is, but few behold, her mind adornd with vertues manifold. Spenser, Amoretti 15 MY mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red, than her lips red: If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damasked, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound: I grant I never saw a goddess go, My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground: And yet by heaven, I think my love as rare, As any she belied with false compare. Shakespeare, Sonnet 130 Some sonnet conventions: 1. The blazon, or inventory of beauties. Embraced by Spenser, Amoretti 15; parodied by Shakespeare, # 130. 2. the power of poetry: Spenser 75 (name on the strand), Shakespeare 18 (summer's day), 19, 55 3. the power of the beloved: Sidney 41 (success in arms), 74 (success in verse due to kiss); Shakespeare 29 (when in disgrace) 4. naturalness, artlessness of verse: Sidney 1 (note hexameters), 74 5. reason versus passion, divine versus earthly: Sidney 5, 52, 71; Spenser 68, 79 6. the feigned renunciation of love: Drayton 61 the conceit: The ingenious, fanciful supposition at the core of a poem that helps to organize it. Often an elaborate figurative device, using metaphor, oxymoron, hyperbole, etc.; often intellectual. (“conceit,” c. 1600 = idea, thought) 1. Wyatt, "Whoso List": hunting 2. Surrey, "Love that doth reign": war (cp. Wyatt, "The Long Love", both translations of Petrarch, Rime 190) 3. Spenser 54: dramatic metaphor 4. Shakespeare 135, Sidney 37: puns on names (Will, Rich) 5. Donne, Holy Sonnet #14: paradoxes ENGLISH 2310 METER QUIZ FALL 2009 Compose two meaningful, original, pentameter iambic unrhymed lines. Sonnets: the problem of address (1) AM I thus conquered? have I lost the powers, That to withstand, which joyes to ruine me? Must I be still, while it my strength devoures, And captive leads me prisoner bound, unfree? Love first shall leave men’s fant’sies to them free, Desire shall quench Love’s flames, Spring, hate sweet showers; Love shall loose all his Darts, have sight, and see His shame, and wishings hinder happy hours. Why should we not Love’s purblind charms resist? Must we be servile, doing what he list? No, seek some host to harbor thee: I fly Thy babish tricks, and freedom do profess; But O my hurt makes my lost heart confess: I love, and must; So farewell liberty. Lady Mary Wroth, Pamphilia to Amphilanthus #16 Sonnets: the problem of address (2) Devouring Time, blunt thou the lion's paws, And make the earth devour her own sweet brood; Pluck the keen teeth from the fierce tiger's jaws, And burn the long-lived phoenix in her blood; Make glad and sorry seasons as thou fleet'st, And do whate'er thou wilt, swift-footed Time To the wide world and all her fading sweets: But I forbid thee one most heinous crime, O carve not with thy hours my love's fair brow, Nor draw no lines there with thine antique pen, Him in thy course untainted do allow, For beauty's pattern to succeeding men. Yet do thy worst, old Time; despite thy wrong, My love shall in my verse ever live young. Shakespeare, sonnet #19 Sonnets: the problem of address (3) A woman's face with Nature's own hand painted, Hast thou, the master mistress of my passion; A woman's gentle heart but not acquainted With shifting change as is false women's fashion; An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling, Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth; A man in hue all hues in his controlling, Which steals men's eyes and women's souls amazeth. And for a woman wert thou first created, Till Nature as she wrought thee fell a-doting, And by addition me of thee defeated, By adding one thing to my purpose nothing. But since she pricked thee out for women's pleasure, Mine be thy love and thy love's use their treasure. Shakespeare, sonnet #20 Sonnets: the problem of address (4) Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest, Now is the time that face should form another, Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest, Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother. For where is she so fair whose uneared womb Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry? Or who is he so fond will be the tomb, Of his self-love, to stop posterity? Thou art thy mother's glass, and she in thee Calls back the lovely April of her prime; So thou through windows of thine age shalt see, Despite of wrinkles, this thy golden time. But if thou live rememb’red not to be, Die single, and thine image dies with thee. Shakespeare, sonnet #3 Sonnets: the problem of address (5) When I do count the clock that tells the time, And see the brave day sunk in hideous night, When I behold the violet past prime, And sable curls all silvered o'er with white: When lofty trees I see barren of leaves, Which erst from heat did canopy the herd And summer's green all girded up in sheaves Borne on the bier with white and bristly beard: Then of thy beauty do I question make That thou among the wastes of time must go, Since sweets and beauties do themselves forsake, And die as fast as they see others grow, And nothing 'gainst Time's scythe can make defence Save breed to brave him, when he takes thee hence. Shakespeare, sonnet #12 Sonnets: the problem of address (6) When in the chronicle of wasted time I see descriptions of the fairest wights, And beauty making beautiful old rhyme In praise of ladies dead, and lovely knights, Then, in the blazon of sweet beauty's best, Of hand, of foot, of lip, of eye, of brow, I see their antique pen would have expressed Even such a beauty as you master now. So all their praises are but prophecies Of this our time, all you prefiguring, And for they looked but with divining eyes, They had not skill enough your worth to sing: For we which now behold these present days, Have eyes to wonder, but lack tongues to praise. Shakeapeare, sonnet #106 Sonnets: the problem of address (6) O thou, my lovely boy, who in thy power, Dost hold Time's fickle glass, his sickle, hour: Who hast by waning grown and therein show'st, Thy lovers withering, as thy sweet self grow'st. If Nature (sovereign mistress over wrack) As thou goest onwards still will pluck thee back, She keeps thee to this purpose, that her skill May time disgrace and wretched minutes kill. Yet fear her, O thou minion of her pleasure, She may detain, but not still keep, her treasure! Her audit (though delayed) answered must be, And her quietus is to render thee. Shakespeare, sonnet #126 Sonnets: the problem of address (7) Batter my heart, three-personed God; for you As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend; That I may rise, and stand, o'erthrow me, and bend Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new. I, like an usurped town, to another due, Labor to admit you, but O, to no end; Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend, But is captived, and proves weak or untrue. Yet dearly I love you, and would be loved fain, But am betrothed unto your enemy: Divorce me, untie or break that knot again, Take me to you, imprison me, for I, Except you enthrall me, never shall be free, Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me. Donne, Holy Sonnet #14 John Donne (1572-1631) Andrew Marvell (1621-1678)