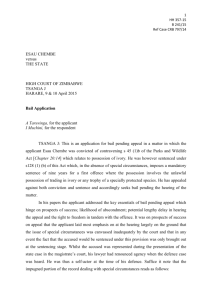

Review of Bail Act 1978 (NSW) Criminal Law Review NSW

advertisement

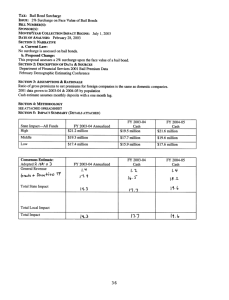

Review of Bail Act 1978 (NSW) Criminal Law Review NSW Department of Justice and Attorney General October 2010 At its heart, the Act is a complex risk assessment scheme balancing three broad principles: 1. The presumption of innocence: bail is not intended to be a form of punishment, nor is a bail determination a judgment of guilt or innocence. 2. Flight risks and Court attendance: in order for the criminal justice system tofunction effectively, accused people must turn up to Court on set dates and an assessment must be made of the likelihood that a person will flee. 3. Protection of the community: an assessment must be made as to whether the accused may commit more offences or interfere with the criminal justice process, for example by interfering with witnesses or evidence, or be a danger to someone else or to him or herself. What is the purpose of bail? As noted in a 1998 NSW Parliamentary paper on bail laws in NSW, there has been a tremendous shift away from the original emphasis of bringing the accused to trial, to an emphasis on protecting the community from possible violent acts while the accused is on bail3 3 As noted in Rachel Simpson’s, NSW Parliamentary Library Research paper, ‘Bail in NSW’, briefing paper No 25/97 1998. The scheme applies to any offence heard in NSW, whether it is against a Commonwealth or NSW criminal law. An application for bail can be made: after charge and before the first appearance at Court (Police bail); during any adjournments before or after the start of the hearing of the case; between committal for trial or sentence, and appearance in the District or Supreme Court; between date of conviction and date of sentence; during any period of the stay of execution of a judgment or sentence, while waiting for the hearing of an appeal; and in various other circumstances. When is bail considered? Police are usually the first authority to consider whether to release an arrested person on bail or not. The rules applying to Police and Court bail are essentially the same. A Police officer of the rank of sergeant or above, or the officer who is in charge of the Police station, is authorised to grant bail as long as a Court has not already decided that bail is to be refused in relation to a particular charge or the requirement for bail has already been dispensed with (s.17). Police Bail How bail works…. In addition to determining which classification an offence falls within, the authorised officer or Court must then consider further criteria as outlined in s.32 of the Act. The criteria include: the probability of whether a person will appear in Court. In this regard a Court can only consider: the person's background and community ties; any previous failure to appear; circumstances of the offence including seriousness and severity of probable penalty; the interests of the person, having regard to length of time likely to be spent on remand and the conditions thereof. the need of the person to be free to prepare for the person’s appearance in Court or to obtain legal advice or both. whether the person is incapacitated by intoxication, injury or drug use or in need of protection. Additional criteria to be considered the protection of the victim and their close relatives and any other person considered to be in need of protection. the protection and welfare of the community, having regard to previous failure to observe a bail condition; likelihood of the person interfering with evidence, witnesses or jurors and likelihood that the person will commit an offence while on bail. the person is under the age of 18 years, or is an Aboriginal person or a Torres Strait Islander, or has an intellectual disability or is mentally ill, and any special needs of the person arising from that fact. the person is a person referred to in section 9B (3), the nature of the person’s criminal history, having regard to the nature and seriousness of any indictable offences of which the person has been previously convicted, the number of any previous such offences and the length of periods between those offences. Additional criteria to be considered If bail is granted, the Police officer, an authorised officer or Court may impose conditions on the accused person (as set out in s.36 & s.36A) for the purpose of promoting further effective law enforcement, for the protection and welfare of any specially affected person or the community, or reducing the likelihood of future offences being committed by promoting the treatment or rehabilitation of an accused person (s.37(1)). Conditions may not be imposed that are any more onerous for the accused person than is required by the nature of the offence or for the protection and welfare of any specially affected person or by the circumstances of the accused person (s.37(2)). Bail may be granted unconditionally or subject to limited conditions. Sections 36(2), 36A, 36B and 37A set out the conditions that may be imposed. They include entering into an agreement to forfeit money, observing certain conditions, attending rehabilitation programs, not to associate with a particular person, not to go to particular place and surrendering a passport. The amendments in relation to intervention programs were introduced in response to the NSW Drug Summit in 1999. Bail may be granted unconditionally or subject to limited conditions. Police have the power to arrest someone if they have reasonable grounds to believe that the person has failed to comply or is about to fail to comply with a bail undertaking or condition (s.50). It is an offence to fail to appear at Court in accordance with a bail undertaking with a maximum penalty equal to the maximum penalty for the offence for which the accused failed to appear or three years or 30 penalty units, whichever is the lesser. No sentence of imprisonment imposed for this offence is to exceed 3 years (s.51). If a Court is satisfied that an accused has failed to appear then the Court may order the forfeiture of any money deposited or agreed to be forfeited (s.53A). An affected person (for example the guarantor) may object to such an order (ss.53C and 53D). Failure to comply with bail undertaking Remand population in NSW As of 30 June 2009 the adult remand population in NSW was 2608.7 The remand population in NSW has been steadily rising since the 30 June 2000. This trend is true for both the male and female remand population. New South Wales has the highest number of unsentenced prisoners in Australia . In 2000, Ms Jacqueline Fitzgerald of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) undertook a study of the remand population in NSW. Fitzgerald found there were several factors contributing to the rise in the remand population: ⋅ the overall number of people appearing in the Local Courts had increased; ⋅ there had been an increase in the number of persons appearing for some offences with a high rate of bail refusal; ⋅ there were indications that Police and magistrates were becoming less willing to grant bail; ⋅ Court delay had increased in the Higher Courts; ⋅ an increase in matters being dealt with summarily, and ⋅ the targeting of repeat offenders by NSW Police Force. Fitzgerald, Jacqueline, Nov 2000. ‘Increases in the NSW Remand Population’, Crime and Justice Statistics, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research. In August 2004, Fitzgerald completed another study on bail, this time analysing the impact of the Bail Amendment (Repeat Offenders) Act 2002. This amendment removed the presumption in favour of bail for various repeat offenders. Fitzgerald found that since the amendments were introduced, the bail refusal rate for defendants appearing in NSW Criminal Courts had increased by 7 per cent. The increase was greatest among defendants targeted by the amendments i.e. those with prior convictions, those appearing for an indictable offence and those who had previously failed to appear.10 There is also evidence that amendments to the Act have resulted in an increase in the general remand population. Fitzgerald J & Weatherburn D “The Bail Amendment (Repeat Offenders) Act 2002” Crime & Justice Bulletin 83 BOCSAR August 2004. The increase in the remand population in NSW has been mirrored in other Australian jurisdictions. In June 2010, there were 29,361 persons in full-time custody in Australia, comprising of 22,535 sentenced and 6,826 unsentenced prisoners. The Australian Capital Territory and South Australia had the highest proportions of unsentenced prisoners (43% and 36% respectively). The lowest proportions of unsentenced prisoners were recorded in Western Australia and Victoria (17% and 19% respectively). New South Wales had the highest number of unsentenced persons in full-time custody, with 2,778 people, followed by Queensland with 1,215.14 The total number of prisoners in Australia has increased by around 20% between 1995 and 2006, but remand numbers have jumped almost 150% over the same period. Remand population in Australia Remanding a person in custody is a serious matter. Remandees awaiting trial enjoy a presumption of innocence, yet they remain incarcerated, often for months at a time. The decision to remand an accused person in custody has consequences for both the individual and the community. The financial and social consequences for the accused include: being unable to care for children or other family members; if employed, losing their job; being deprived of their liberty and unable to participate in ordinary life; difficulty in preparing their defence to the charge; incurring a stigma associated with being in prison, and if they are not found guilty of the charges, the hardship they have suffered by being on remand cannot be redressed. The consequences of remand For the community there are also both financial and social ramifications. Financially, remanding accused persons in custody involve both the high cost of incarceration for the State and the cost of enforcing Court decisions and attendance, as well as any delays to the Court operations. The average cost per day to keep a prisoner in custody in NSW is $187.14 for open custody, and $216.85 for secure custody. The average cost per juvenile in custodial services in NSW in 2006-2007 was $543.19. Socially, the community is faced with the problem of reintegrating into society those who have served time on remand who have lost their job and community connections. The consequences of remand The consequences of remand Chilvers M, Allen J and Doak P, May 2002. ‘Absconding on Bail’, Bulletin – Contemporary Issues in Crime and Justice No. 68, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research. Remanding a person into custody is not, however, a decision which courts take lightly. In order for the criminal justice system to function effectively, accused people must turn up to Court on set dates and an assessment must be made of the likelihood that a person will flee. Similarly, an assessment must be made as to whether the accused may commit more offences or interfere with the criminal justice process, for example by interfering with witnesses or evidence, or be a danger to someone else or to him or herself. Research indicates that a large number of people on bail fail to appear. There are costs associated with their detection and arrest as well as the risk of further offences. In 2008, around 5.5% of accused persons in the Local Court failed to appear and warrants were issued for their arrest. In Higher Courts, the rate was around 0.2%. While these are significant reductions from 2001, where the rates were around 10.5% and 3% respectively, there is concern that some of these accused persons continue to commit offences whilst on bail. It is therefore important for bail laws to be carefully balanced to ensure that accused people are only remanded where it is necessary to achieve the stated aims of the bail scheme. Chilvers M, Allen J and Doak P, May 2002. ‘Absconding on Bail’, Bulletin – Contemporary Issues in Crime and Justice No. 68, NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research. Where the “presumption against bail” classification applies the accused must satisfy the Court that bail should not be refused. This presumption has attracted a considerable sum of controversy for the following reasons: the classification operates against the presumption of innocence and the requirement that the prosecution must prove the case against the accused there is a significant pressure to plead guilty to a minor offence, if an accused cannot get bail; and there is little redress for those who are refused bail and ultimately are acquitted. Source: Cran v State of NSW [2004] NSWCA 92. Presumption against Bail