PowerPoint Presentation - Weird Ways People Think About Money

advertisement

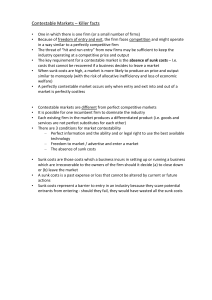

Weird Ways People Think About Money • People think about money in ways that make no sense to an economist. Some of these phenomena were already covered as motivation for the introduction of Prospect Theory (recall the examples of loss aversion). • Today we’ll look at a couple of new quirks - Mental Accounting and Sunk Costs. • We’ll try to understand both the pitfalls and the attractions of these ways of thinking about money. Not All Dollars Are Created Equal • Imagine that you’ve bought a ticket to a hit Broadway play.At the theater you realize you’ve lost your ticket which cost $100 but you have enough money in your wallet to replace it. Do you spend another $100 to see the performance? • Now imagine the same scenario, except you’re planning to buy the ticket when you arrive. At the box office, you realize you’ve lost a $100 bill out of your wallet. Still you have more than enough to buy the ticket. Do you? • Many people answer “No” and “Yes”,respectively, although the bottom line is the same in each case. How Mental Accounting Works • People who say “No” in the first instance reason that spending what amounts to $200 for a play is just too extravagant. • They say “Yes” in the second example because they mentally put the first $100 in the category of “bad luck” and the second $100 in the category of cost of entertainment. • In each case we would be out $200 at the end of the day - and so in each case we can either afford to see the play or we can’t - but our little mental accounting system sees a significant difference between the two. A Really Bizarre Example • On your way home you buy a TV dinner for $3 using a discount coupon. As you prepare to cook it, you get the idea of inviting a friend over. Your friend says sure.When you go back to the grocery you have to pay the regular price of $5 for the identical dinner. You go home and cook both dinners but your friend then cancels. Both dinners are cooked. You are not hungry enough to eat both and don’t want to freeze it. You must eat one and discard the other. Which one do you eat? • Out of 89 people in the study, 21 people said they would eat the $5 dinner! (It seems less wasteful!) Should You Use Your Savings Account to Pay Off Your Credit Card? • An accountant would say, Yes. (Your savings account is drawing 8% interest at most; your credit card is costing you 16% at least.) • But from a budgeting point of view it might be disastrous, especially if you were to then run up your credit card again! • Mental accounting can help us budget but when it gets tied too strongly to past circumstances it leads to irrationalities. What Will You Do With Your Tax Refund? • Many people treat a tax refund as an unexpected bonus or “mad money” and spend it in ways that they would never think of spending money in their savings account. • (This is also the way people often treat a jackpot they make at a casino - it doesn’t feel “real” money and they put it back in play.) • So if one were able to decrease the money withheld for taxes just enough so that one would get zero refund and have it put into a savings account instead, one would undoubtedly spend that same sum of money in quite different ways. Is It Still Grandma’s Money? • Other times we label unexpected money as “sacred”. If Grandma leaves us money unexpectedly, we may decide that we should be very careful with this windfall and keep it in savings instead of investing it. • The economist would say we should think this way: First, we add the inheritance to our overall financial picture. Now we forget about the history of the various dollars that we own and ask: given my new overall financial situation, do I need to invest some money? If so, then I go balance my portfolio. If I also want to honor Grandma in some way, then do so directly. Money is fungible completely interchangeable. Sunk Cost Trap • You and your companion have driven half-way to a resort. Responding to a reduced-rate advertisement, you have previously made a non-refundable $100 deposit to spend the weekend there. Both you and your companion feel slightly bad physically and out of sorts psychologically. • Your assessment of the situation is that you and your companion would have a much more pleasurable weekend at home. • Your companion says it's "too bad" you have reserved the room because you both would much rather spend the time at home, but you can't afford to waste $100. You agree. Further, you both agree that given the way you feel now, it is extraordinarily unlikely you will have a better time at the resort than you would at home. • Do you drive on or turn back? • If you drive on, you are behaving as if you prefer paying $100 to be where you don't want to be than to be where you want to be. Good Money After Bad: The Sunk Cost Fallacy • Imagine you’ve been given a courtside ticket to a Chicago Bulls game back when Michael Jordan was playing. Before you leave the house you learn that Jordan is sick and won’t be playing, plus a big snow storm makes the trip dangerous.Do you go anyway? • Same scenario except this time you paid a small fortune for the ticket and can’t resell it. Do you go? • Note that in each case, going will “cost” you the unpleasant trip out to a not very exciting game. Why should you be more willing to do this in the case where you’ve already spent a lot? Why should the history of how you got the ticket affect you decisions about the future? What’s Wrong With Including Sunk Costs? • Both the above are examples of what economists call the "sunk-cost fallacy"--the human tendency to judge options according to the size of previous investments rather than the size of the expected return. • Truly rational choices would be made looking only at future costs and benefits. • Many proverbs remind us of this. – What’s done is done. – Don’t throw good money after bad. – No use crying over spilt milk. • So where does this human tendency come from? Does it have any function? Re-Thinking Some of the Cases • Let’s go back to the couple going to the resort. Are there any good reasons for driving on? • Well, they might perk up when they got there. (But of course that would be true if they hadn’t already made the reservation.) • Perhaps neither wants to appear fickle - the kind of person who can’t follow through on plans and hence may be unreliable. But this worry is really about the future and we are no longer dealing with a sunk cost, strictly speaking. • Similarly, taking responsibility for one’s own past decisions may contribute to future satisfaction. The Cost of Not Admitting Past Mistakes • The judgments of professional basketball coaches are also blighted by sunk costs. They should play and keep their most productive players, but Barry Staw and Ha Hoang at Berkeley found that players’ salaries significantly affected both these decisions. • The most expensive players were given more time on court and kept on the team longer than cheaper players, even after adjusting for variables such as performance, injuries and the positions they played. The Cost of Pride • Sometimes countries are reluctant to end wars without total victory because they don’t want people saying that the early casualties“died in vain”. • Governments and businesses frequently keep spending new money on expensive projects even as it becomes clearer and clearer that the project will lose even more money. • Some have called sunk costs the “Concorde effect”. Trying to Play Catch-Up • In one of the earliest studies of the fallacy, Staw asked business school students to play the role of corporate executives who had to allocate research and development funds to divisions of their own companies. The students received feedback on their initial decisions and were then asked to make a second investment. • They put significantly more money into failing investments than successful ones, and they invested even more money if they themselves were responsible for the earlier decision rather than another (unidentified) executive. Do Animals Respond to Sunk Costs? • Dawkins was surprised to discover what looked like Concorde fallacy behaviour in female digger wasps. These wasps paralyse katydids--a sort of grasshopper--with a sting, and drag the bodies to their burrows. Once they have collected four or five katydids, they lay a single egg that hatches and feeds on the paralysed but still living katydids. Sometimes there's a mix-up and two wasps end up putting katydids in the same burrow. When they eventually bump into one another, they fight for the right to lay their egg in the burrow. Fights end when the loser gives up and retreats. Yes - It First Appeared • According to observations made by Jane Brockmann of the University of Florida in Gainesville, how long the losing wasp keeps fighting depends on how many katydids she has already placed in the burrow-that is, the investment to date-rather than the total number of katydids in the burrow. • The second option would be the rational basis for such a decision because it alone dictates how much future effort the wasp must make to fully stock its larder. Maybe Not After All • When Dawkins and Brockmann put their heads together, they came up with another explanation for the wasps' apparently irrational behaviour. Plainly each wasp knows how many katydids she placed in her burrow because that dictates how long she fights. (She probably doesn't actually count the number of katydids, but assesses it indirectly, perhaps by sensing how much time she spent flying back and forth from the burrow.) She is, however, unable to tell whether another wasp is stashing katydids in her burrow until she meets her rival, so it's probably safe to say that she has trouble counting the total number of katydids that are there. Projecting to the Future • As the wasp cannot be said to be ignoring information she does not have access to, she can hardly be held to be committing a fallacy. The two researchers concluded that the number of katydids each wasp puts in its burrow is simply the best estimate of the burrow's future worth. In that case, it makes sense for a wasp to fight longer the more katydids it has put in. • So this is not a case of making a decision on the basis of a sunk cost per se. Rather the sunk cost provides a basis for predicting the future value. So this is not a case like the Concorde.