Succeed Under Pressure Pressure as a way of life by Professor

Succeed Under Pressure

Pressure as a way of life by Professor Rakesh Sondhi

Succeed under pressure is a book that took 2 years to write and is based on combining the learning from the experiences of a professional footballer and a practicing business consultant. Gary Bailey is an ex Manchester

United (over 400 appearances) and England goalkeeper, and Rakesh Sondhi, an international strategy and leadership consultant.

A review of the book was covered in the January edition of Management Today

SA. This series of articles will look at themes from each chapter and extract perspectives of high performers from different environments, such as athletes and business people, in the ways they handle pressure when they need to perform.

In this issue we have interviewed one of the greatest British footballers of all time, Bryan Robson, ex Manchester United and England captain, affectionately known as Captain Marvel by his adoring fans (the author included). Bryan is able to offer a number of unique perspectives, as he was also a high profile manager in the English Premier League at Middlesbrough and West Bromwich Albion, as well as Sheffield United, Bradford City and Thailand. In addition, Bryan was a shareholder and Director of the then hugely successful Birthdays retail chain, a nationwide collection of retail shops specializing in cards for special occasions.

A key objective in these articles is to combine popular theory with practices from exceptional performing people. In particular, we will explore current thinking in neuroscience to help better understand how we can improve our levels of performance in pressure situations.

Considerable work has been done on understanding why some people fail to perform in situations where there is considerable pressure. Pressure situations increases the likelihood of stress, which in turn can cause anxiety, and in some cases depression. Consequently, this leads to deterioration in the performance of individuals.

The symptoms of pressure are also caused by over activity in key areas of the brain. Research has shown that there are certain activities we undertake, which have been learned in our early years that are part of our procedural memory.

This means we do not need to think about these activities, as they are carried out with no thought – a little like driving a car. These activities are undertaken in an unconscious way. Athletes and sportspeople, for example, learn their skills that drive their exceptional performance at a very young age and as such become second nature to them. For example, Bryan Robson learned to play football from

a very young age, so his responses in pressure situations relied heavily on his

“natural” skills and talents that were developed from his younger years.

Activities that are learned later in life tend to involve greater activity in the pre frontal cortex part of the cerebrum (see below), which develop as we get older and the pre frontal cortex evolves. As a result we use more of our working memory when undertaking these tasks. The working memory refers to the amount of conscious thought given to undertaking an activity. Consequently, under pressure people can spend too much time over analyzing situations, rationalising expectations and as a result they end up “choking” (2) when they need to deliver. People tend to spend too much time thinking about different outcomes, rather than simply visualising a positive outcome. This is sometimes termed “paralysis by analysis”.

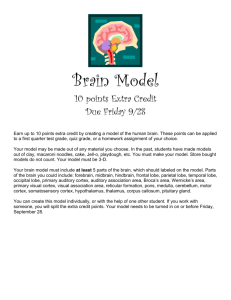

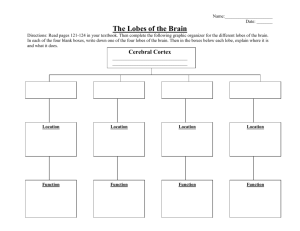

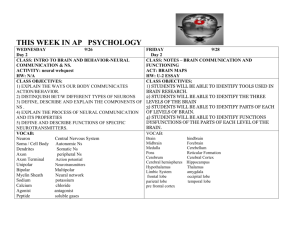

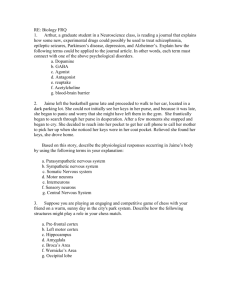

From a neuroscience perspective, the largest part of the brain is the cortex or cerebrum, which is further divided into 4 lobes, that are responsible for key functions or skills that determine our level of performance in different activities.

The Cerebrum

Occipital lobe

Visual association cortex and the primary visual cortex

AREA OF

BRAIN

Frontal lobe

Parietal lobe

KEY ELEMENTS

Motor association cortex, primary motor cortex, primary somatosensory cortex and prefrontal cortex

Somatosensory association cortex

KEY FUNCTIONS

Reasoning, planning, organizing thoughts, behavior, sexual urges, emotions, problemsolving, judging, organizing parts of speech, and motor skills (movement).

Information processing, movement, spatial orientation, speech, visual perception, recognition, perception of stimuli, pain and touch sensation and cognition.

Visual reception, visual-spatial processing, movement and color recognition. Disorders of the occipital lobe can cause visual

Temporal lobe

Auditory association cortex and the visual association cortex, as well as the hippocampus, basal ganglia, amygdala and fornix illusions.

Distinguishing and discrimination of smell and sound from other smells and sounds respectively. Between them, they control visual memory (right lobe) and verbal memory (left lobe), and thus, hearing, speech and memory.

The hippocampus processes long-term memory and also is important for spatial learning and memory. The basal ganglia control movement. The amygdala processes emotions. The fornix connects the hippocampus to other parts of the brain.

Before progressing to our interview with Bryan Robson it is important to establish what we mean by human performance. Human Performance is characterized by mental skills to apply knowledge, an attitude and willingness to overcome obstacles in the environment, and physical skills and attributes to deliver desired outcomes.

High Performance may be shown in the following formula:

Performance = ((Knowledge + Skills) * Attitude)/Roadblocks in the environment

(1)

Where,

Knowledge + Skills = The ability to perform

Roadblocks in the environment = The opportunity to perform

Attitudes = the willingness to perform

Each of these attributes is developed through activity in specific areas of the brain, as shown above. Each area of the brain contributes to the ability to perform and the willingness to perform. Our assessment of the environment defines the level of opportunity. The frontal lobe is essentially activated to assist in our assessment of the environment in a rational way.

Pressure is defined, and experienced, by people in different ways. In some cases the words may be perceived quite negatively, whilst in others it is seen from a very positive view.

Bryan Robson described the impact of pressure in different ways in different circumstances. As a player he never felt the nervousness or stress caused by pressure. He always saw the big games, where the pressure was greater, as a challenge that inspired him to raise his game, even higher than usual. Robson described how he felt excited by the pressure, which is clearly a very positive perspective of pressure. He remembers playing in finals and semi finals of cup

competitions and being excited, looking forward to the game, and always thinking of the best scenario in the game, thinking of scoring a goal, for example.

This positive perspective also reinforces the research that suggests the brain has to do the same work and energy whether it is thinking about something in a positive or negative perspective. The brain fails to differentiate between the two, but the negative perspective usually reflects in a failed outcome. For example, when a football player takes a penalty kick and thinks to himself ‘don’t miss”, the chances are that he will miss as his brain is constantly thinking about missing!

Instead, he should be visualizing himself scoring so that this picture is fixed in his brain. Therefore the key lesson is that the brain should look at situations involving pressure from a positive perspective.

Robson also spoke about how emotions differed when playing in less important games or games involving a weaker team. He did admit that there was much less nervousness, and consequently, less time was spent thinking prior to the game.

However, in 1983, Manchester United were playing Brighton in the FA Cup final, as heavy favourites, and Robson mentioned how the level of nervousness was increased due to a number of reasons. Firstly, this happened to be his first final and he was desperate to win a major trophy and also there was an increased expectation as United were expected to win, as they were perceived to be the stronger team. The first game ended as a draw, largely due to a great save from my co-author of “Succeed Under Pressure”, Gary Bailey. Robson mentioned that once Gary had made the save he started thinking that Brighton have had their chance and that confidence started to grow as they prepared for the replay, which United won 4-0!

Bryan Robson was renowned for being on the top of his game in key matches. He always performed when he had to. In 1984, Manchester United played Barcelona in the European Cup Winners Cup. In the away leg Robbo had a chance to score, but assumed he was offside, so just nonchalantly kicked the ball onto the cross bar. However, he was on side and had wasted an absolutely good chance. In the return match Robson had one of his greatest games, leading United to a 3-0 win.

He said that he was desperate to prove himself after his miss. This demonstrated that Robbo played with his heart on his sleeve and that pressure caused an excitement and challenge that raised his performance level.

As a manager, Robson described how his feelings of pressure changed, He described how as a player he felt in control and all he had to do was focus his concentration and preparation on himself. When he moved into football management he felt the pressure more as he had to focus on all the players and staff. In addition, there was considerable pressure placed by the newspapers, where they constantly referred to previous great players who failed to become great managers. This is sometimes referred to as the “stereotype threat” where an individual knows they are capable of doing something, and doing it well, but the typical stereotype adds greater pressure causing the individual to choke when it matters. Robson also added that as a great player he was used to winning, but as a manager he struggled to get used to not winning. This desire to win was also transferred in his role as director of the successful retail chain at the time, Birthdays. He saw this as a way of getting away from the day-to-day

pressure of football, but was able to transfer his natural positivity and enthusiasm into another sector.

Summarizing in relation to the performance equation Robson, the player, clearly possessed the ability to play and had the desire and willingness to play. He also had a clear understanding of his environment as he had been brought up on this over many years of competitive practice. As a manager, he had an ability to perform, to a point, but much of his learning of leadership and management was gained from playing and observing some of the finest managers in the world, but he had not experienced a structured training programme as he had as a player.

In addition, he had not previously practiced leadership in a competitive environment. He was learning on the job. His understanding of his environment was also not as well developed when he started as a manager. Therefore he had to learn very quickly, but was very dependent on his working memory, rationalizing success and failure.

The key lessons from this article are:

1.

Football, as with other sports, is practiced under a state of competition.

Training sessions in high-level sports is intense due to the competition for places in the team. As a result, players’ brains are programmed to perform under a state of pressure. Many footballers we have spoken suggest that the intensity of training sessions is actually greater than the games themselves.

2.

Athletes view failure as a chance to improve performance next time. This competitive attitude in sportspeople is key to creating winners.

3.

Don’t rely too much on working memory, as this will tend to over rationalize situations under pressure. Perhaps in Bryan Robson’s case as a player he relied heavily on his procedural memory, for skills he learned as a youngster. As a manager maybe he was more reliant on his working memory causing him to over rationalize situations.

4.

Focus on what you want to do, not on what you should not do e.g. the situation with preparing for a penalty kick.

For further details of the authors and discussions of “Succeed Under Pressure” go to www.successunderpressure.com, www.garybaileyspeaks.com and www.Rakeshsondhi.com

“Succeed Under Pressure” is available from above and www.BMCGlobalServices.com

References:

1.

Peters, D.A. (2007), “The Performance Equation – A unifying theory of performance”, white paper

2.

Bellock, S (2011) reprint, “Choke: What the secrets of the brain reveal about getting it right when you have to”, Free Press