I t

advertisement

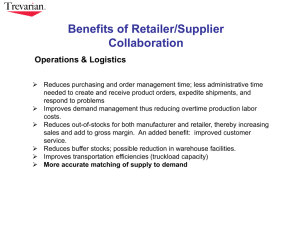

A Dynamic Mechanism for Achieving Sustainable Quality Supply Tracy Lewis Fang Liu1 Jeannette Song Fuqua School of Business, Duke University 1Nanyang Business School, Nanyang Technological University December 2014 Starbucks Growth 8 7 6 5 4 Fiscal Year End Store Counts 3 2 1 US International 20 00 20 01 20 02 20 03 20 04 20 05 20 06 0 600 500 400 Net Earnings ($Millions) 300 200 100 0 '95 '96 '97 '98 '99 '00 '01 '02 '03 '04 '05 '06 '07 20 00 20 01 20 02 20 03 20 04 20 05 20 06 15000 14000 13000 12000 11000 10000 9000 8000 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 Annual Revenues ($Billions) The Coffee Supply Chain Worldwide, 25 million small producers rely on coffee for a living Farmers/producers 50% Latin America 35% Pacific Rim 15% East Africa Suppliers Processors Make green coffee Areas of coffee cultivation Exporters Distributors Mktg & financing Technical expertise Logistics Retailers Over 2.25 billion cups of coffee are consumed in the world every day Commodity chain for the coffee industry C.A.F.E. Practices (Coffee and Farmer Equity Practices) Coffee buying guidelines to support coffee buyers and coffee farmers – 1. Ensure high quality coffee and equitable relationship with farmers Prerequisites for Starbucks suppliers – – 2. Product quality: green preparation and cup quality Economic accountability: financial transparency, viability, equity pay Supplier grading/rewarding system on environmental and social criteria (weighted scoring sheet, up to 100 points) – – Social responsibility: Non-discrimination & employee quality of life, occupational health, safety & living condition (60) Environmental leadership: conservation of natural resources and impact on environment, growing (20), processing (20) 4 Supplier Incentives • Level 1 Total score > 60 points Preferred pricing & contract terms, prioritized purchases • Level 2 Total score > 80 points Premium of $0.05 per pound on green coffee prices for first year • Level 3 Second year with 10% increase in scores over Level 2 Additional premium of $0.05 per pound Sustainable Quality Supply • Other examples – Wal-Mart: local organic produce – Coca-Cola: pure water • Common features – Demand for large quantity of high quality supply – Foresee shortage in the near future – Sequential investments to hedge against future risk • Challenges – – – – – Supplier development Long-term commitment Changing environment / private information Voluntary participation Self-enforceability Research Questions • Are the existing industry guidelines such as C.A.F.E. sufficient for achieving sustainable supply quality in the long run? – Ex post efficiency • Do they also encourage first-best initial and continued supplierdevelopment investments? – Ex ante efficiency • If the current practice is not successful, when to stop? – Termination conditions Approach: Dynamic mechanism design Model Setting Supplier (s) Retailer (r) Market • Collaborate for T periods, discount factor d • Product quality (prerequisite, fixed) • Sustainability index 0 < x < 1 (current sustainability level) – Single aggregated measure • Social and environmental aspects (measured by score card) • Weighted scores – Commonly observed • Third-party certified – Jointly agreed with payments adjusted, so no rejections by retailer (Additional) Production Cost and Investment • In period t, supplier incurs an additional cost (over that for x=0) C ( x t , q st ) – Increasing and convex in xt t – Increasing and concave in s – Supermodular t • s 0, s : production conditions in period t – Technological readiness, labor market conditions, soil and weather conditions – Private information to supplier – Morkov process, depending on improvement investment It and st 1 st ~ Fst | st 1 , I t t t t 1 t t e.g., s s s I s Adjusted Market Revenue • In period t, the retailer receives adjusted revenue R ( x t , q rt ) – – – – Additional revenue + tax credit Increasing and concave in xt Increasing and convex in rt Supermodular • r 0, r : current demand conditions in period t t – Consumer’s valuation of sustainability: environmental awareness, social awareness, general economic conditions, tax credit – Private information to retailer – Markov process rt ~ Frt | rt 1 e.g., rt rt rt 1 rt Benchmark: Supply-Chain Optimal Solution • Optimal expected discounted supply-chain profit from period t on • For any given index: , supply-chain ex-post optimal sustainability • Optimal single-period supply chain profit • Optimal ex-ante investment Questions for Decentralized Chain • Short term goal: How to provide incentives to achieve xt* in each period? – What should be the payment structure? • We do not assume a fixed payment type – How does the payment depend on market and production environment? – How to ensure long-term commitment? • Long term goal: How to ensure optimal supply-chain investments It*? – Retailer invests to improve θst – Supplier development – Investment amount is private information, relationship specific Literature Review Methodology o Supply chain contracts: repeated interactions o o o Relational contracts o Plambeck and Taylor (2006) o Tunca and Zenios (2006) o Taylor and Plambeck (2007a,b) Investment efficiency o Plambeck and Taylor (2007) Dynamic mechanism design o Lutze and Ozer (2008) o Zhang, Nagarajan and Sosic (2010) o Oh and Ozer (2012) o Li , Zhang and Fine (2013) Principal-agent framework – no full coordination o Dynamic mechanism design o o o Bergemann and Valimaki (2006, 2010) (w/o BB) Athey and Segal (2007a, b) (w/o IR) Lewis, Liu & Song (2012) – dynamic ownership Ours: Partnership & commitment – full coordination Modeling • Quality as contract terms – Baiman, Fischer & Rajan (2000) – Lim (2001) – Iyer, Schwarz & Zenios (2005) – Zhu, Zhang & Tsung (2007) – Kaya and Ozer (2009) Ours: Jointly decide index x, dynamic model Structure of the Mechanism • A sequence of investment strategies I determines a multi-period direct mechanism: M x , | I t – Sustainability index • t T t 1 is the set of possible period t reported histories – Payments • is payments to member i after material is supplied • The mechanism induces a dynamic game Sequence of Events Stage 1: ex-ante decision to participate stage Stage 2: investment stage Stage 3: ex-post decision to participate stage Stage 4: reporting stage Period t time Period t+1 Supplier stay? Supplier stay? no yes no yes Retailer invests Itr Supplier observes st Retailer observes rt ~ Supplier reports st 1) Select index, x t ~ Retailer reports rt 2) Make payments, τt 1) 2) 3) 4) Supplier quits without penalty The partnership ends and cannot be fixed Retailer invests 0 in the future Retailer purchases from the market with sustainability index 0 5) Supplier supplies the market with sustainability index 0 Retailer decides whether to commit to M at the beginning of period 1 Payoffs of Each Player Expected optimal profit to go given the other member’s reporting strategy • Retailer • Supplier Desired Equilibrium • Supply chain transparency (Bayesian incentive compatible BIC): – Truth-telling is the mutual best response: • First-best outcome – Ex ante efficient investments (EE1): – Ex post efficient sustainability index (EE2): • Voluntary participation – Ex ante Interim individual rational (IIR1): – Ex post Interim individual rational (IIR2): • Self-enforceability (Budget balancing BB): and Constructing the Mechanism (Without Investment) • To ensure BIC, let expected supply chain profit – participation fee • Member i will not lie -- he/she receives all the values he/she contributed to the system • For every realization of st , supplier’s willingness to pay is • Supplier’s willingness to pay under her worst off type is • To ensure IIR2, supplier’s participation fee has to be less than her willingness to pay under every possible st Constructing the Mechanism (Cont.) (Without Investment) • To ensure BB, total participation fee must exceed supply chain profit • Thus, set • To ensure EE2, set Adjusting Transfer Payments Net transfer payment for member i Transfer that ensures the first-best index Expected participation payment for t, ensures self-enforceability Expected participation payment for t+1, ensures supply chain transparency Net transfer payment achieves ex-ante budget balance Adjust to ensure ex-post budget balance Payment Structure • Two-part nonlinear tariff A bottom-line price fixed at the beginning of the period depending on the previous period’s conditions + A real-time payment equals the current period supply chain profit based on the current period’s sustainability index and the current period’s environmental conditions + A real-time payment equals the expected continuation supply chain profit based on the current period’s environmental conditions Different from C.A.F.E. Supply Chain Optimal Investments and Retailer’s Commitment T • Modified mechanism M xt* , t*|I * specifies contract terms according to t 1 production cost distribution under optimal investment Fst* Fst | st 1 ,I t* • Retailer’s expected profit before he invests in period t • Retailer’s best response is the supply chain optimal investment (EE1) I rt* I t* t* t* • If It* is unique, then I r I is the unique equilibrium t* t* * T • Retailer commits to M x , |I if and only if t 1 Sustainable Quality Supply Agreement (SQSA) • The mechanism – – – – – ~ M x , h t | I * * t * T t 1 ensures Supply chain transparency (BIC) Voluntary participation (IIR1, IIR2) Optimal ex ante investments (EE1) Optimal ex post sustainability index (EE2) Budget balance: self-enforceability (BB) Here, Example: Coffee Supply Chain time Identical stationary distributions of the production and market condition • Linear cost/revenue R x t , rt x t rt C x t , st x t st • • Retailer invests in technological innovation, success rate is p • Let • Define , Coffee Example: SQSA Properties Price of free will Sustainable practice Unsustainable practice • Threshold policies on T, for fixed p • Threshold policies on p, for fixed T Region A + Region B = retailer terminates the current contract and start a new sustainable practice Coffee Example: Supplier Development Dynamics Total collaboration: 1 - 10 years Year 1 Year 10 Year 8 High cost years • Years 1 to 7 • When x>0, production cost = 2 Starbucks: when x=1, market revenue = 1 time Low cost years • • Years 8 to 10 Production cost = 0 Coffee Example: Supplier Development (cont.) Total collaboration:10 years Year 1 Year 10 Year 8 time High cost years Low cost years • Year 1 to 7 • When x>0, production cost = 2 Starbucks: when x=1, market revenue = 1 • Year 8 to 10 • Production cost = 0 Cost of investment = 1 With probability p grower’s cost reduce to zero Year 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 V*t (7p+2)v3 (6p+2)v3 (5p+2)v3 (4p+2)v3 (3p+2)v3 (2p+2)v3 3 3 2 Invest if p≥ 1/7 1/6 1/5 1/4 1/3 ½ 1 1 1 1 1 Observations • It is not necessarily optimal to select a high sustainability index in every period because it may not be economically sustainable • The real-time payments depend not only on the sustainability index (the first transfer) but also on the market condition (the third transfer) • For any given success rate p, when the contract length T increases, the retailer is more likely to invest in more periods • With longer contract length T, the supplier is more likely to invest in a wider range of suppliers (with smaller cutoff success rate) • For any given success rate p, the retailer will continue SQSA if the remaining contract length T is longer than a certain threshold max(T0 ,T1), which is neither convex nor concave in p Summary • Designed a T-period agreement (SQSA) for the supply chain members to collaborate to achieve supply-chain optimal sustainability level and investment – Suggesting new elements and payment calculations to add to the existing sustainability initiatives – Confirming long-term collaboration encourages investments • Key: – Shared-surplus type of mechanism – residual claimant – Dynamically adjusted payment scheme, reflecting both current performance and environmental effects • Can be generalized to N members in series