Document

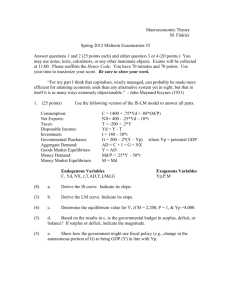

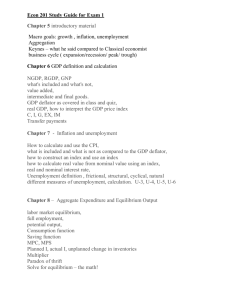

advertisement

Aggregate Demand I: Building the IS-LM Model Chapter 11 of Macroeconomics, 8th edition, by N. Gregory Mankiw ECO62 Udayan Roy THE GOODS MARKET IN THE SHORT RUN Recap: Long-Run Theory of Output • As before, let Y denote total real GDP • Recall that, in the long run, total real GDP is calculated as Y = F(K, L) – The economy produces as much as it can • Total real GDP in the long run is also called: – Natural GDP, or – Potential GDP • From now on, total long-run real GDP will be denoted 𝒀 = F(K, L) Actual Output ≠ Potential Output • In the short run, total real GDP is not necessarily equal to natural GDP, or potential GDP • Y≠𝒀 • We need a new theory of Y, because the longrun theory—𝑌 = F(K, L)—no longer works Short-Run Theory of Output: it’s all about demand • The short-run theory of total real GDP is also called – Keynesian theory, after the economist John Maynard Keynes, or – Aggregate Demand Theory • This theory assumes that, in the short run, output is determined by aggregate demand: the economy will produce as much output as there is demand for The simplest theory of short-run equilibrium in the goods market THE KEYNESIAN CROSS Planned Expenditure • Assumption: The economy is a closed economy • Planned Expenditure (PE) is the total desired expenditure of the three sectors of the economy: – Households (C) – Businesses (I) and – Government (G) • PE = C + I + G Consumption Expenditure • PE = C + I + G • What determines the planned expenditure of households (C)? – We did this before in chapter 3 Consumption, C • Net Taxes = Tax Revenue – Transfer Payments – Denoted T and always assumed exogenous: 𝑻 = 𝑻 • Recall that GDP is defined as the market value of all final goods and services produced in an economy during a given period of time • But this is also actual total expenditure, • which is also actual total income • Therefore, Y also represents actual total income • Disposable income (or, after-tax income) is total income minus total net taxes: Y – T. • Assumption: planned consumption expenditure (C) is directly related to disposable income (Y – T) Consumption, C • Assumption: Planned expenditure by households is directly related to disposable income • Consumption function: C = C (Y – T ) Consumption Function: algebra • Consumption function: C = C (Y – T ) • Specifically, C = Co + Cy✕(Y – T) • Co represents all other exogenous variables that affect consumption, such as asset prices, consumer optimism, etc. • Cy is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC), the fraction of every additional dollar of income that is consumed Consumption Function: graph C C (Y –T) = Co + Cy✕(Y – T) MPC 1 The slope of the consumption function is the MPC. Co Y–T Marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is the increase in consumption (C) when disposable income (Y – T) increases by one dollar. It is also Cy. Consumption Function: shifts C C = Co2 + Cy✕(Y – T) C = Co1 + Cy✕(Y – T) Consumption shift factor: higher consumer optimism, higher asset prices (Co↑). Y Consumption Function: shifts C C = Co + Cy✕(Y – T2) C = Co + Cy✕(Y – T1) The same shift can also be caused by lower taxes. (T2 < T1) Y Consumption Function: example • • • • Suppose Y = 30.85 and T = 0.85. Therefore, disposable income is Y – T = 30. Now, suppose C = 2 + 0.8 ✕ (Y – T). Then, C = 2 + 0.8 ✕ 30 = 26 Private Saving is defined as disposable income – consumption, which is Y – T – C = 30 – 26 = 4. Y C C(Y – T), T Income and Private Saving • The marginal propensity to consume is a positive fraction (0 < MPC < 1) • That is, when income (Y) increases, consumption (C) also increases, but by only a fraction of the increase in income. • Therefore, Y↑⇒ C↑ and Y – C↑ and Y – T – C↑ • Similarly, Y↓⇒ C↓ and Y – C↓ and Y – T – C↓ Planned Investment • PE = C + I + G • Assumption: Planned investment spending by businesses (I) is exogenous • This assumption is a big deal. • Recall that business investment was endogenous in long-run analysis of chapters 3, 8 and 9. Government Spending • PE = C + I + G • Assumption: government spending (G) is exogenous • Public Saving is defined as the net tax revenue of the government minus government spending, which is T – G – This is also called the budget surplus Planned Expenditure • PE = C + I + G • Therefore, PE = C(Y – T) + I + G • Or, more specifically, PE = Co + Cy✕(Y – T) + I + G Equilibrium • Assumption: The goods market will be in equilibrium. That is, actual expenditure will be equal to planned expenditure. Actual and planned expenditure • Actual and planned expenditure do not have to be equal in all circumstances • Actual expenditure = planned expenditure + unplanned increase in inventory – When unplanned increase in inventory > 0, more is bought than was intended. – When unplanned increase in inventory < 0, less is bought than was intended. Equilibrium • When unplanned increase in inventory > 0, more is bought than was intended. • So, actual expenditure > planned expenditure • In this case, output will shrink • In other words, the current output level cannot represent equilibrium Equilibrium • When unplanned increase in inventory < 0, less is bought than was intended. • So, actual expenditure < planned expenditure • In this case, output will increase • In other words, the current output level cannot represent equilibrium Equilibrium • For an economy to be in equilibrium, unplanned increase in inventory must be zero • Therefore, actual expenditure = planned expenditure + unplanned increase in inventory = planned expenditure • But recall that actual expenditure is actual GDP or Y, and planned expenditure is C + I + G • Therefore, in equilibrium, Y = C + I + G Short-Run GDP: calculation • • • • We just saw that in equilibrium Y = C + I + G Therefore, Y = Co + Cy ✕ (Y – T) + I + G This is one equation with one unknown, Y So, this equation can be used to solve for Y – Example: C = 2 + 0.8✕(Y – T), T = 0.85, G = 3, and I = 1.85 – Then, Y = 2 + 0.8✕(Y – 0.85) + 1.85 + 3 – Check that Y = 30.85 Short-Run GDP: calculation • In equilibrium, Y = C + I + G Y Co C y (Y T ) I G Y Co C yY C yT I G Y C yY Co C yT I G (1 C y ) Y Co C yT I G Y Co C yT I G 1 Cy At this point, you should be able to do problems 2 and 4 on pages 325-26 of the textbook. Please try them. Every variable on the right hand-side of the equation is exogenous. So, this equation tells us everything we can say about Y in the Keynesian Cross model. Short-Run GDP: predictions Y Co C yT I G 1 Cy Every variable on the right hand-side of the equation is exogenous. So, this equation tells us everything we can say about Y in the Keynesian Cross model. Important: Note that there is absolutely no reason why this shortrun equilibrium GDP has to be equal to the long-run equilibrium GDP (𝒀). Predictions Grid Y Co + T − I + G + In other words, the Keynesian Cross model is able to explain why recessions and booms happen. The Keynesian Cross Equation Y Co C y T I G 1 Cy Cy 1 (Co I G ) T 1 Cy 1 Cy The Spending Multiplier Cy 1 Y (Co I G ) T 1 Cy 1 Cy • Note that for every $1.00 increase in Co + I + G, Y increases by $1/(1 – Cy). • As Cy is the marginal propensity to consume, 1/(1 – Cy) may be written as 1/(1 – MPC). • This is called the spending multiplier. The Spending Multiplier Cy 1 Y (Co I G ) T 1 Cy 1 Cy • As the marginal propensity to consume is a positive fraction (0 < MPC < 1), 1 – MPC is also a positive fraction. • Therefore, 1/(1 – MPC) > 1. • So, for every $1.00 increase in Co + I + G, Y increases by more than $1.00! The Spending Multiplier Cy 1 Y (Co I G ) T 1 Cy 1 Cy • The spending multiplier is 1/(1 – MPC). • Example: If MPC = 0.2, the spending multiplier = 1/(1 – 0.2) = 1.25. Therefore, if the government spends $3 billion on a new highway, real GDP will increase by $3.75 billion • Example: If MPC = 0.8, the spending multiplier = 1/(1 – 0.8) = 5. Therefore, if the government spends $3 billion on a new highway, real GDP will increase by $15 billion • The bigger MPC is, the bigger the spending multiplier will be. Why??? The Tax-Cut Multiplier Cy 1 Y (Co I G ) T 1 Cy 1 Cy • Note that for every $1.00 decrease in T, Y increases by $Cy/(1 – Cy). • As Cy is the marginal propensity to consume, Cy /(1 – Cy) may be written as MPC/(1 – MPC). • This is the tax-cut multiplier. The Tax-Cut Multiplier Cy 1 Y (Co I G ) T 1 Cy 1 Cy • As the marginal propensity to consume is a positive fraction (0 < MPC < 1), At this point, you should be able to do problem 1 on page 325 of the textbook. Please try it. – MPC/(1 – MPC) < 1/(1 – MPC) – Tax-cut multiplier < spending multiplier – That is, a $1.00 tax cut provides a smaller boost to the economy than a $1.00 increase in government spending. Why?? The Tax-Cut Multiplier Cy 1 Y (Co I G ) T 1 Cy 1 Cy • The tax-cut multiplier is MPC/(1 – MPC). • Example: If MPC = 0.2, the tax-cut multiplier = 0.2/(1 – 0.2) = 0.25 < 1. Therefore, if the government cuts taxes by $3 billion, real GDP will increase by $0.75 billion • Example: If MPC = 0.8, the tax-cut multiplier = 0.8/(1 – 0.8) = 4. Therefore, if the government cuts taxes by $3 billion, real GDP will increase by $12 billion Fiscal Policy • The practice of changing the levels of government spending (G) and/or taxes (T) in order to affect the macroeconomic outcome is called fiscal policy – Spending more (G↑) and/or cutting taxes (T↓) is called expansionary fiscal policy – Spending less (G↓) and/or raising taxes (T↑) is called contractionary fiscal policy Fiscal Policy • The consequences of expansionary and contractionary fiscal policy in the Keynesian Cross model were analyzed in previous slides • In any case, they can be easily seen from the Keynesian Cross model’s equation: Cy 1 Y (Co I G ) T 1 Cy 1 Cy K.C. Spending multiplier K.C. Tax-cut multiplier Fiscal Policy: balanced budget multiplier • Note that expansionary fiscal policy (G↑ and/or T↓) leads to lower public saving (T – G↓) – This could mean a rise in the budget deficit or a fall in the budget surplus • Is there no way to stimulate an economy in a recession while keeping the budget balanced? • There is! Fiscal Policy: balanced budget multiplier • What happens if both G and T increase by $1? • The $1 increase in G increases Y by 1/(1 – MPC) • The $1 increase in T decreases Y by MPC/(1 – MPC) • Therefore, the total change in Y is 𝐶𝑦 1 − 𝐶𝑦 1 ∆𝑌 = − = =1 1 − 𝐶𝑦 1 − 𝐶𝑦 1 − 𝐶𝑦 • This is the balanced budget multiplier Fiscal Policy: balanced budget multiplier • The balanced budget multiplier shows that if both government spending and taxes are increased by the same amount—thereby keeping the budget balanced—then output will increase by the same amount. Graphing planned expenditure PE planned expenditure PE =C +I +G MPC 1 income, output, Y Graphing the equilibrium condition PE PE =Y planned expenditure 45º income, output, Y The equilibrium value of income PE planned expenditure PE =Y PE =C +I +G Output gap Y Equilibrium income 𝒀, natural rate of output An increase in government purchases PE At Y1, there is now an unplanned drop in inventory… PE =C +I +G2 PE =C +I +G1 G …so firms increase output, and income rises toward a new equilibrium. Y PE1 = Y1 Y PE2 = Y2 Solving for Y Y C I G equilibrium condition Y C I G in changes C G MPC Y G Collect terms with Y on the left side of the equals sign: (1 MPC) Y G because I exogenous because C = MPC Y Solve for Y : 1 Y G 1 MPC The government purchases multiplier Definition: the increase in income resulting from a $1 increase in G. In this model, the govt Y 1 purchases multiplier equals G 1 MPC Example: If MPC = 0.8, then Y 1 5 G 1 0.8 An increase in G causes income to increase 5 times as much! Why the multiplier is greater than 1 • Initially, the increase in G causes an equal increase in Y: Y = G. • But Y C further Y further C further Y • So the final impact on income is much bigger than the initial G. An increase in taxes PE Initially, the tax increase reduces consumption, and therefore PE: PE =C1 +I +G PE =C2 +I +G At Y1, there is now an unplanned inventory buildup… C = MPC T …so firms reduce output, and income falls toward a new equilibrium Y PE2 = Y2 Y PE1 = Y1 Solving for Y eq’m condition in changes Y C I G I and G exogenous C MPC Y T Solving for Y : Final result: (1 MPC) Y MPC T MPC Y T 1 MPC The tax multiplier def: the change in income resulting from a $1 increase in T : Y T MPC 1 MPC If MPC = 0.8, then the tax multiplier equals Y T 0.8 0.8 4 1 0.8 0.2 The tax multiplier …is negative: A tax increase reduces C, which reduces income. …is smaller than the spending multiplier: Consumers save the fraction (1 – MPC) of a tax cut, so the initial boost in spending from a tax cut is smaller than from an equal increase in G (or Co or Io). NOW YOU TRY: Practice with the Keynesian Cross • Use a graph of the Keynesian cross to show the effects of an increase in planned investment on the equilibrium level of income/output. Tax Cuts: JFK • Kennedy cut personal and corporate income taxes in 1964 • An economic boom followed. – GDP grew 5.3% in 1964 and 6.0 in 1965. – Unemployment fell from 5.7% in 1963 to 5.2% in 1964 to 4.5% in 1965. • However, it is not easy to prove that the tax cuts caused the boom • Even when they agree that the tax cuts caused the boom, economists can’t agree on the reason Tax Cuts: JFK • Keynesians argued that the tax cuts boosted demand, which led to higher production and falling unemployment • Supply-siders argued that demand had nothing to do with it. The tax cuts gave people the incentive to work harder. So, L increased. Therefore, Y = F(K, L) also increased. – Personally, I feel this argument doesn’t explain why the unemployment rate fell Tax Cuts: GWB • Bush cut taxes in 2001 and 2003 • After the second tax cut, a weak recovery from the 2001 recession turned into a strong recovery – GDP grew 4.4% in 2004 – Unemployment fell from its peak of 6.3% in June 2003 to 5.4% in December 2004 • In justifying his tax cut, Bush used the Keynesian explanation: – “When people have more money, they can spend it on goods and services. … when they demand an additional good or service, somebody will produce the good or service.” Spending Stimulus: Barack Obama • When President Obama took office in January 2009, the economy had suffered the worst collapse since the Great Depression • Obama helped enact an $800 billion (5% of annual GDP) stimulus to be spent over a twoyear period • About 40% was tax cuts, and 60% was additional government spending – White House economists had estimated the spending multiplier to be 1.57 and the tax-cut multiplier to be 0.99 Spending Stimulus: Barack Obama • Much of the new spending was on infrastructure projects • These projects were fine for the long run, but took a long time to be implemented, and were therefore not ideal as a short-run boost • Obama publicly justified his stimulus bill using Keynesian demand-side reasoning A slightly more complex theory of short-run equilibrium in the goods market THE IS CURVE Planned Investment • The Keynesian Cross model assumed that planned expenditure by businesses (I) is exogenous • Recall that, in chapter 3, we had assumed that investment spending is inversely related to the real interest rate • The IS Curve theory of the goods market brings back the investment function I = I(r) The Real Interest Rate • Recall from chapter 3 that, the real interest rate is the inflation-adjusted interest rate • To adjust the nominal interest rate for inflation, you simply subtract the inflation rate from the nominal interest rate – If the bank charges you 5% interest rate on a cash loan, that’s the nominal interest rate (i = 0.05). – If the inflation rate turns out to be 3% during the loan period (π = 0.03), then you paid the real interest rate of just 2% (r = i − π = 0.02) The Real Interest Rate • The problem is that when you are taking out a loan you don’t quite know what the inflation rate will be over the loan period • So, economists distinguish between – the ex post real interest rate: r = i − π – and the ex ante real interest rate: r = i − Eπ, where Eπ is the expected inflation rate over the loan period – We will use the ex ante interpretation of the real interest rate Investment and the real interest rate • Assumption: investment spending is inversely related to the real interest rate • I = I(r), such that r↑⇒ I↓ r I (r ) I Investment and the real interest rate • Specifically, I = Io − Irr • Here Ir is the effect of r on I and • Io represents all other factors that also affect business investment spending – such as business optimism, technological progress, etc. r Io2 − Irr Io1 − Irr I Investment: example • Suppose I = 11.85 – 2r is the investment function • Then, if r = 5 percent, we get I = 11.85 – 2r = 1.85. The IS Curve • Recall that the goods market is in equilibrium when Y = C + I + G • The IS curve is a graph that shows all combinations of r and Y for which the goods market is in equilibrium • Therefore, the basic equation underlying the IS curve is Y = C(Y – T) + I(r) + G Deriving the IS Curve: algebra Y C (Y T ) I (r ) G Y Co C y (Y T ) I o I r r G Y Co C y Y C y T I o I r r G Y C y Y Co C y T I o I r r G (1 C y ) Y Co C y T I o I r r G Cy 1 Ir Y (Co I o G ) T r 1 Cy 1 Cy 1 Cy K.C. Spending multiplier K.C. Tax-cut multiplier IS Interest rate effect Deriving the IS Curve: algebra So, although the basic equation underlying the IS curve is … Y C (Y T ) I (r ) G … for my specific consumption and investment functions, the equation underlying the IS curve can also be expressed as: Cy 1 Ir Y (Co I o G ) T r 1 Cy 1 Cy 1 Cy The two equations are equivalent forms of the IS curve. Comparing the Equations of the Keynesian Cross and the IS Curve Keynesian Cross Cy 1 Y (Co I o G ) T 1 Cy 1 Cy K.C. Spending multiplier K.C. Tax-cut multiplier This is the only difference IS Curve Cy 1 Ir Y (Co I o G ) T r 1 Cy 1 Cy 1 Cy K.C. Spending multiplier K.C. Tax-cut multiplier IS Interest rate effect The IS Curve Cy 1 Ir Y (Co I o G ) T r 1 Cy 1 Cy 1 Cy K.C. Spending multiplier K.C. Tax-cut multiplier r IS Interest rate effect Any change in the real interest rate will cause an opposite change in real total GDP by a multiple determined by the size of the interest rate effect. r1 Δr r2 This is why the IS curve is negatively sloped. IS Y1 Y2 ΔY Y The IS Curve: effect of fiscal policy Cy 1 Ir Y (Co I o G ) T r 1 Cy 1 Cy 1 Cy K.C. Spending multiplier Any increase in Co + Io + G causes the IS curve to shift right by the amount of the increase magnified by the Keynesian Cross spending multiplier That is, if the real interest rate is unchanged, the Keynesian Cross model is the same as the IS curve model. K.C. Tax-cut multiplier IS Interest rate effect r r1 Y IS1 Y1 Y2 IS2 Y The IS Curve: effect of fiscal policy Cy 1 Ir Y (Co I o G ) T r 1 Cy 1 Cy 1 Cy K.C. Spending multiplier Any decrease in taxes (T) causes the IS curve to shift right by the amount of the tax cut magnified by the Keynesian Cross tax-cut multiplier K.C. Tax-cut multiplier IS Interest rate effect r r1 Y IS1 Y1 Y2 IS2 Y The IS Curve: shifts • To sum up the previous two slides: • The IS curve shifts right if there is: – an increase in Co + Io + G, or – a decrease in T. Deriving the IS curve: graphs PE =Y PE =C +I (r )+G 2 PE r PE =C +I (r1 )+G I PE I Y Any change in the real interest rate will cause an opposite change in real total GDP by a multiple determined by the size of the interest rate effect. r Y1 Y Y2 r1 r2 IS Y1 Y2 Y The natural rate of interest • Recall chapter 3 gave us a long-run theory of the real interest rate • At the long-run interest rate, both – Y = C + I + G (or, equivalently, S = I) and – Y=𝒀 – are true. • Note that 𝒓 in the diagram satisfies the requirements of longrun equilibrium • This is the natural rate of interest PE = Y PE PE = C + I(𝒓) + G PE = C + I(r1) + G r Y1 Y 𝒀 r1 𝒓 IS Y1 𝒀 Y The natural rate of interest will reappear in chapter 14. But there it will be denoted ρ. (Confused???) Why the IS curve is negatively sloped • A fall in the interest rate motivates firms to increase investment spending, which drives up total planned spending (PE). • To restore equilibrium in the goods market, output (a.k.a. actual expenditure, Y) must increase. Fiscal Policy and the IS curve • We can use the IS-LM model to see how fiscal policy (G and T) affects aggregate demand and output. • Let’s start by using the Keynesian cross to see how fiscal policy shifts the IS curve… Shifting the IS curve: G At any value of r, G PE Y PE =Y PE =C +I (r )+G 1 2 PE PE =C +I (r1 )+G1 …so the IS curve shifts to the right. The horizontal distance of the IS shift equals r Y1 Y Y2 r1 1 Y G 1 MPC Y Y1 IS1 Y2 IS2 Y NOW YOU TRY: Shifting the IS curve: T • Use the diagram of the Keynesian cross or loanable funds model to show how an increase in taxes shifts the IS curve. The theory of short-run equilibrium in the money market THE MONEY MARKET IN THE SHORT RUN: THE LM CURVE The Theory of Liquidity Preference • The theory of short-run equilibrium in the money market is exactly the same as the theory of long-run equilibrium in the money market that we saw in Chapter 5 – Please review Chapter 5 Review of Ch. 5 Money demand and the interest rate • Liquid assets are assumed to earn no interest • Illiquid assets are assumed to earn the nominal interest rate i • Therefore, an increase in i is assumed to reduce the demand for money • That is, money demand (Md) is assumed to be inversely related to the nominal interest rate (i) Review of Ch. 5 Money demand and the price level • We also hold some of our wealth in the form of money—in liquid form—because money is an excellent medium of exchange Review of Ch. 5 Money demand and the price level • Recall that nominal GDP is the market value of all final goods and services • It is also the total expenditure on all final goods and services • Therefore, the bigger our nominal GDP, the bigger will be our need for money, as money is a medium of exchange • It is, therefore, assumed that money demand is directly related to nominal GDP Review of Ch. 5 Money demand and the price level • Let P represent the overall level of prices, as measured by the GDP Deflator Nominal GDP • From Chapter 2: GDP Deflator = Real GDP • Therefore, Nominal GDP = GDP Deflator × Real GDP = 𝑷 × 𝒀 • It is, therefore, assumed that money demand (Md) is directly related to nominal GDP (𝑷 × 𝒀) Review of Ch. 5 Money Demand • So, Md is – inversely related to i, and – directly related to PY • 𝑴𝒅 = 𝑳(𝒊) × 𝑷 × 𝒀 – L(i) is the liquidity function – It is inversely related to i, the nominal interest rate Review of Ch. 5 Money Demand: example • 𝑴𝒅 = 𝑳(𝒊) × 𝑷 × 𝒀 – L(i) is the liquidity function – It is inversely related to i, the nominal interest rate • Specific form of L(i): – 𝑳(𝒊) = 𝑳𝟎/𝒊 – Lo represents all factors other than P, Y and i that also affect money demand Review of Ch. 5 Money Demand = Money Supply • M denotes money supply • 𝑴𝒅 = 𝑳(𝒊) ∙ 𝑷 ∙ 𝒀 denotes money demand • Therefore, 𝑴 = 𝑳(𝒊) ∙ 𝑷 ∙ 𝒀 denotes equilibrium in the money market Review of Ch. 5 Money Demand = Money Supply • 𝑴 = 𝑳(𝒊) ∙ 𝑷 ∙ 𝒀 • 𝑌= 𝑀 𝐿 𝑖 ∙𝑃 • For the specific form 𝑳(𝒊) = 𝑳𝟎/𝒊, the above equation becomes • 𝒀= 𝑴 𝑳𝟎 /𝒊 ∙𝑷 = 𝑴∙𝒊 𝑳𝟎 ∙𝑷 Money Demand = Money Supply • 𝒀= 𝑴∙𝒊 𝑳𝟎 ∙𝑷 • Now, recall that the ex ante real interest rate is the nominal interest rate minus the expected inflation rate: r = i – Eπ • Therefore, r + Eπ = i • So, the money market equilibrium equation becomes 𝒀 = 𝑴∙ 𝒓+𝑬𝝅 𝑳𝟎 ∙𝑷 At this point, you should be able to do problem 5 on page 326 of the textbook. Please try it. The LM Equation • So, for the specific form 𝑳(𝒊) = 𝑳𝟎/𝒊, the money market equilibrium equation then becomes • 𝒀= 𝑴∙ 𝒓+𝑬𝝅 𝑳𝟎 ∙𝑷 • Traditionally, this equation is called the LM equation Money Demand = Money Supply • 𝒀= 𝑴∙ 𝒓+𝑬𝝅 𝑳𝟎 ∙𝑷 • Assumption: As always, the money supply (M), which is controlled by the central bank, is exogenous • Assumption: unlike the long-run analysis of Chapter 5, expected inflation (Eπ) is exogenous. • Assumption: unlike the long-run analysis of Chapter 5, the overall price level (P) is exogenous Prices are sticky in the short run • Recall that the long-run analysis of Chapter 5 assumed that P is endogenous. – Recall also that in the long run P changes proportionately with M. • The short-run analysis in the IS-LM model assumes that P is exogenous: it is what it is, it is historically determined – That is, the overall price level is “sticky”: what it was last week, it will be this week too Prices are sticky in the short run • This sticky-prices assumption is the crucial distinction between long-run and short-run macroeconomic analysis • Except this assumption, all assumptions made in short-run analysis are also assumed in longrun analysis • So, the differences between long-run and short-run theories are caused by this stickyprices assumption Money Demand = Money Supply • LM equation: 𝒀 = 𝑴∙ 𝒓+𝑬𝝅 𝑳𝟎 ∙𝑷 • Note that if the real interest rate (r) increases, the real GDP (Y) must increase too, in order to keep money demand equal to money supply The LM Curve: algebra to graph • The LM curve shows all combinations of r and Y for which the money market is in equilibrium • Note that the LM curve is upward rising 𝑴 ∙ 𝒓 + 𝑬𝝅 𝒀= 𝑳𝟎 ∙ 𝑷 r LM r2 r1 Y1 Y2 Y The LM Curve: algebra to graph 𝑴 ∙ 𝒓 + 𝑬𝝅 𝒀= 𝑳𝟎 ∙ 𝑷 • The LM curve shifts (down) right if: – M/P or Eπ increases – Lo decreases • Moreover, if Eπ increases (decreases), the LM curve shifts down (up) by the exact same amount! r LM1 LM2 r1 r2 Y0 Y NOW YOU TRY: Shifting the LM curve • Suppose a wave of credit card fraud causes consumers to use cash more frequently in transactions. • Use the liquidity preference model to show how these events shift the LM curve. Both the goods market and the money market need to be in equilibrium SHORT-RUN EQUILIBRIUM IN THE IS-LM MODEL Short-run equilibrium The short-run equilibrium is the combination of r and Y that simultaneously satisfies the equilibrium conditions in both the goods and money markets: Y C (Y T ) I (r ) G r LM IS M L(r E ) P Y Equilibrium interest rate Y Equilibrium level of income Short-run equilibrium By insisting that both the goods market and the money market need to be in equilibrium, we have managed to find a way to pinpoint both r and Y simultaneously! r LM IS Y C (Y T ) I (r ) G M L(r E ) P Y Equilibrium interest rate Y Equilibrium level of income Short-run equilibrium Note that the short-run equilibrium GDP does not have to be equal to the long-run equilibrium GDP (𝑌, also called potential GDP and natural GDP) r LM Thus, like the Keynesian Cross model, the IS-LM model can explain recessions and booms. But, the Keynesian Cross model could determine only equilibrium GDP. The IS-LM model determines the equilibrium interest rate as well. Equilibrium interest rate IS 𝒀 Equilibrium level of income Y The IS-LM Model: summary • Short-run equilibrium in the goods market is represented by a downward-sloping IS curve linking Y and r. • Short-run equilibrium in the money market is represented by an upward-sloping LM curve linking Y and r. • The intersection of the IS and LM curves determine the short-run equilibrium values of Y and r. • The IS curve shifts right if there is: r – an increase in Co + Io + G, or LM – a decrease in T. • The LM curve shifts right if: – M/P or Eπ increases, or – Lo decreases IS Y The Big Picture Keynesian Cross Theory of Liquidity Preference IS curve LM curve IS-LM model Agg. demand curve Agg. supply curve Explanation of short-run fluctuations Model of Agg. Demand and Agg. Supply Preview of Chapter 12 In Chapter 12, we will – use the IS-LM model to analyze the impact of policies and shocks. – learn how the aggregate demand curve comes from IS-LM. – use the IS-LM and AD-AS models together to analyze the short-run and long-run effects of shocks. – use our models to learn about the Great Depression.