Objectives and Content - LSA Introduction to Criminal Justice

advertisement

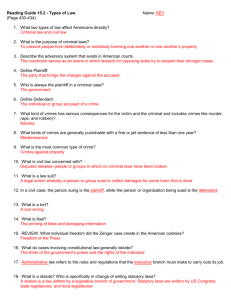

Criminal Law and Procedure: Objectives and Content Unit 1: Elements of Criminal Law (9 weeks) Objectives: CLP.1.1 Describe the difference between criminal statutes and judicial opinions. Content: 1. Criminal statutes set forth the elements that need to be proven in order to find a defendant guilty of committing a crime (Va. Code §18.2-388 (2012) (example of an enacted criminal law)). 2. Judicial opinions apply a specific set of facts to a criminal law, thereby explaining the criminal law (Crislip v. Com., 37 Va. App. 66 (Va. Ct. App. 2001) and Rogers v. Pendleton, 249 F. 3d 279 (4th Cir. 2001) (examples of statutes being defined by case law)). 3. Criminal laws are further defined as either mala in se (actions society recognizes as inherently bad) or mala prohibitum (actions society does not recognize as inherently bad but are nevertheless criminalized) (Barron’s Law Dictionary 306, 307 (5th Ed. 2003)) CLP.1.2 Describe the elements of criminal laws. Content: 1. Mens rea (guilty mind) must be demonstrated (Morissette v. U.S., 342 U.S. 246 (1952)). a. Mens rea can be read into statutes when it appears that the legislature intended for that to occur Com. v. Hensley, 7 Va. App. 468 (Va. Ct. App. 1988)). b. There is no mens rea requirement for strict liability crimes Esteban v. Com., 266 Va. 605 (Va. 2003)). 2. Actus reus (guilty act) must be demonstrated (U.S. v. Parks, 411 F. Supp. 2d 846 (S.D. Ohio 2005)). 3. Mens rea and actus reus must occur concurrently (at the same time) (Clay v. Com, 30 Va. App. 254 (Va. Ct. App. 1999)). 4. The defendant’s act must be the proximate cause of the criminal harm (Brown v. Com., 278 Va. 523 (Va. 2009)). 5. Corpus delicti (actual harm) must be proven (Williams v. Com., 234 Va. 168 (Va. 1987)). CLP.1.3 Analyze the differences between general criminal laws and inchoate offenses. Content: 1. Solicitation is when one person attempts to persuade another person to commit a crime (Va. Code §18.229 (1975) and Armes v. Com., 3 Va. App. 189 (Va. Ct. App. 1986)). 2. An attempt in Virginia is not directly defined by statute (Va. Code §18.2-26 (1975)), but is instead based on common law: a. A common law attempt is an unfinished crime (inchoate offense) composed of two elements (Johnson v. Com., 209 Va. 291 (Va. 1968)): i. The intent to commit the crime, and ii. Doing some direct act toward its consummation, but falling short of the accomplishment of the ultimate design. b. A defendant can be convicted of attempt even if he abandons the act (Howard v. Com., 207 Va. 222 (Va. 1966)). 3. Conspiracy is when one person conspires with another person to commit a crime (Va. Code §18.2-22 (1983) and 21 U.S.C. §846 (1988)). a. Conspiracy is composed of three elements (U.S. v. Strickland, 245 F. 3d 368 (4th Cir. 2001)). i. There is an agreement between people to engage in conduct that violates the law ii. These people know about the conspiracy, and iii. These people knowingly and voluntary participate in the conspiracy. b. There are two different types of conspiracies: i. A “chain conspiracy,” where one suspect works with a second suspect who works with a third suspect in support of one goal (U.S. v. Hitow, 889 F. 2d 1573 (6th Cir. 1989) (chain conspiracy)). ii. A “hub and spoke conspiracy,” where a suspect (the hub) engages with other suspects (the spokes) to commit multiple conspiracies in support of one goal (U.S. v. Mathis, 216 F. 3d 18 (D.C. 2000)). CLP.1.4 Examine the classification of criminal laws. Content: 1. Felonies are crimes punishable by death or confinement in prison of more than one year (Va. Code §§18.2-8 (1975), Va. Code §§18.2-9 (1975), and Va. Code §§18.2-10 (2008)). 2. Misdemeanors are punishable by a fine or confinement in jail of less than a year (Va. Code §§18.2-8 (1975), Va. Code §§18.2-9 (1975), and Va. Code §§18.2-11 (2000)). CLP.1.5 Examine the classification of suspected offenders. Content: 1. Principals are classified into two groups: a. A principal in the first degree is the instigator and moving spirit in perpetrating a crime; he directs and assists his associates in the actual commission (Hancock v. Com., 12 Va. App. 774 (Va. Ct. App. 1991)). b. A principal in the second degree is present during the crime, aids and abets the act done, or keeps watch or guard at some convenient distance (Hancock, supra). 2. Accessories are classified into two groups: a. An accessory to the crime is identical to principal in the second degree except that he is not physically or constructively at the scene (Hancock, supra). b. There are three elements to prove that a suspect is an accessory after the fact (Com. v. Dalton, 259 Va. 249 (Va. 2000)): i. The felony must be complete ii. The accused must know that the felon is guilty, and iii. The accused must receive, relieve, comfort or assist the felon. CLP.1.6 Evaluate the recognized defenses to violating a criminal law. Content: 1. There is a difference between ignorance of the law and a mistake regarding the law. a. Ignorance of the law is not an excuse for committing a criminal act (Com. V. Thompson, 10 Va. Cir. 278 (Va. Cir. Ct 1987)). b. A mistake of the law is a limited defense when the accused, because of mistake as to a separate non-penal law, lacks the mens rea necessary to establish guilt for a criminal act (U.S. v. Bickley, 50 M.J. 93 (C.A.A.F. 1999)). 2. The insanity of the defendant at the time of the crime is a defense, but this type of defense varies. a. The M’Naghten rule (the rule in Virginia and most states) defines a person as insane if, at the time he committed the act, he could not tell right from wrong (Price v. Com., 228 Va. 452 (Va. 1984)). b. The “irresistible impulse test” defines a person as insane if he should or did not know that his actions were illegal but, because of mental impairment, he couldn’t control his behavior (State v. Wilson, 306 S.C. 498 (S.C. 1992)). c. The “Durham rule” (“product test”) defines a person as insane if his unlawful act was the product of mental disease or defect (Durham v. U.S., 214 F. 2d 862 (D.C. 1954)). d. The “Insanity Defense Reform Act” defines a person as insane if the defendant, as a result of a severe mental disease or defect, was unable to appreciate the nature and quality or the wrongfulness of his acts (18 U.S.C. §17 (1986) and U.S. v. Westcott, 83 F. 3d 1354 (11th Cir. 1996)). e. The “Substantial Capacity Test” (Model Penal Code) defines a person as insane if mental illness has deprived him of effective power to make the right choices in governing his own behavior (and Com. v. McHoul, 352 Mass. 544 (Mass. 1967)). 3. The intoxication of a defendant at the time of the crime is a defense in certain cases. a. Involuntary intoxication is a defense to certain crimes and is relied on when a person without his willing and knowing use of intoxicating liquor, drugs, or other substances (Com v. Shumway, 72 Va. Cir. 481 (Va. Cit. Ct. 2007)). b. Voluntary intoxication is not a defense to any crime; however, voluntary intoxication can negate the deliberation and premeditation required for certain crimes (Downing v. Com., 26 Va. App. 717 (Va. Ct. App. 1998)). 4. The age of a defendant at the time of the crime is a defense in certain cases (State v. Rudy B., 149 N.M. 22 (N.M. 2010)). a. Children under the age of seven are deemed incapable of forming mens rea to commit a crime. b. The common law infancy defense (children ages seven to fourteen) is a rebuttable presumption that, while a child demonstrated actus reus, he should be relieved from liability because he did not understand the moral consequences of his actions and is not culpable (lack of mens rea). c. Children over the age of fourteen have the same capacity as adults under common law. 5. Entrapment is a the conception and planning of an offense by an officer and his procurement of its commission by one who would not have acted except for the officer’s trickery, persuasion or fraud (McCoy v. Com., 9 Va. App. 227 (Va. Ct. App. 1989)). 6. Justification is a series of defenses where the accused admits he committed the criminal act but is not accountable because he was justified in his actions. The defenses include: a. The victim’s effective consent or the actor’s reasonable belief that the victim consented to the conduct excuses an otherwise criminal act (Miller v. State, 312 S.W. 3d 209 (Tex. Ct. App. 2010)). b. Self-defense: i. Excuses or justifies a homicide or assault committed while repelling violence towards the defendant so long as it is a response to the threat of death or serious bodily harm (Hughes v. Com., 43 Va. App. 391 (Va. Ct. App. 2004)). ii. The “castle doctrine” (stand your ground) allows the use of non-deadly force to protect a home (Com. v. Alexander, 260 Va. 238 (Va. 2000)). iii. The “castle doctrine” is being extended to include the use of deadly force to protect a home (F.S.A. §776.012 (2005)). c. Duress excuses acts that are normally criminal where the defendant shows that the acts were the product of threats inducing a reasonable fear of immediate death or serious bodily injury (Zelenak v. Com., 23 Va. App. 259 (Va. Ct. App. 1996)). d. Necessity is identical to duress except that it requires pressure from physical, natural causes (State v. Castrillo, 112 N.M. 766 (N.M. 1991)). Unit 2: Crimes Against People (4 weeks) Objectives: CLP.2.1 Evaluate the legal classifications of homicide Content: 1. Homicide is the killing of a human being by the act, procurement, or omission of another, death occurring at any time, and is either: (1) murder, (2) manslaughter, (3) excusable homicide, or (4) justifiable homicide (RCWA 9A.32.010 (1975)). a. Murder includes the killing of a human being without the authority of law by any means or in any manner Miss. Code Ann. § 97-3-19 (2004)). b. Manslaughter is the unlawful killing of a human being without malice (I.C. § 18-4006 (2009)). c. Homicide is excusable if committed by accident and misfortune in doing any lawful act, with usual and ordinary caution (SDCL § 22-16-30 (2005)). d. Homicide is justifiable when, for example, it is committed in self-defense by one who reasonably believes that he is in imminent danger of losing his life or receiving great bodily harm and that the killing is necessary to save him from that danger (LSA-R.S. 14:20(1) (2006) (justifiable homicide)). 2. There are four specific types of homicide crimes. a. Capital murder, which in Virginia are specific crimes deemed eligible for the death penalty (a. Code §18.2-31 (2010)). b. First and second degree murder, which are defined as follows: i. For first degree murder, a homicide resulting from the accuser’s willful, deliberate, and premeditated acts, i.e., specific intent to kill (Va. Code §18.2-32 (1998) and Stokes v. Warden, 226 Va. 111 (Va. 1983)). ii. For second degree murder, a homicide resulting from a general intent to kill (Va. Code §18.2-32 (1998) and Epperly v. Com. 224 Va. 214 (Va.1982)). c. Felony murder, which is the killing of one accidentally, contrary to the intention of the parties, while in the prosecution of some felonious act other than first or second degree murder (Va. Code §18.2-33 (1999) and Diehl v. com., 9 Va. App. 191 (Va. Ct. App. 1989)). d. Manslaughter, which is delineated as follows (I.C. § 18-4006 (2009)). i. Voluntary manslaughter is homicide upon a sudden quarrel or heat of passion ii. Involuntary manslaughter is homicide upon the commission of an unlawful act or in the commission of a lawful act which might produce death, in an unlawful manner, or without due caution and circumspection; or in the operation of any firearm or deadly weapon in a reckless, careless or negligent manner which produces death. iii. Vehicular manslaughter in which the operation of a motor vehicle is a significant cause contributing to the death because of the commission of an unlawful act with or without gross negligence. 3. The doctrine of transferred intent allows for the transfer of a defendant's criminal intent to harm the intended victim to another unintended victim (Blow v. Com., 52 Va. App. 533 (Va. Ct. App. 2008)). CLP.2.2 Describe the difference between criminal assault and criminal battery. Content: 1. Assault and battery are separate criminal acts even though states combine them into one statute (Va. Code §18.2-57 (2011)). 2. Criminal Assault is an attempt or offer, with force and violence, to do some bodily hurt to another (Parish v. Com., 56 Va. App. 324 (Va. Ct. App. 2010)). 3. Criminal battery is a willful or unlawful touching of another, which includes injury to the victim's mind or feelings (Parish, supra). CLP.2.3 Analyze the difference between robbery and larceny. Content: 1. Robbery is defined as the taking, with intent to steal, of the personal property of another, from his person or in his presence, against his will, by violence or intimidation (Com. v. Hudgins, 269 Va. 602 (Va. 2005) (robbery)). 2. Robbery differs from larceny in that proof of violence or intimidation is required in a prosecution for robbery but not for grand larceny from the person. And proof of the value of the property stolen is required in a prosecution for grand larceny from the person but not for robbery (Hudgins, supra). CLP.2.4 Describe laws prohibiting abduction and kidnapping. Content: 1. Criminal abduction and kidnapping terms which are used interchangeably, is defined as the act of a person who, by force, intimidation or deception, and without legal justification or excuse, seizes, takes, transports, detains or secretes another person with the intent to deprive such other person of his personal liberty or to withhold or conceal him from any person, authority or institution lawfully entitled to his charge (Va. Code §18.2-47 (2009)). a. Child abduction is considered kidnapping (Bennett v. Com., 8 Va. App. 228 (Va. Ap. Ct. 1989)). b. Criminal kidnapping does not include false imprisonment, which is a civil remedy (Lewis v. Kei, 281 Va. 715 (Va. 2011)). CLP.2.5 Describe laws prohibiting genocide. Content: 1. Genocide is defined by international treaty as any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group by (Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court art. 6, 17 July 1998): a. Killing members of the group, b. Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group, c. Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part, d. Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group, or e. Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. 2. The specific laws regarding genocide are drafted by the tribunal charged with trying offenders. a. One example is the Nuremburg Trials (Charter of Int’l Military Tribunal art. 6, 8 Aug. 1945). b. A second example is the Rome Statute (Rome Statute of the Int’l Criminal Court, supra). CLP.2.6 Analyze the differences between domestic terrorism and attacks by foreign nationals. Content: 1. Terrorism is statutorily defined by statute as a separate and distinct criminal act (8 U.S.C. § 2331 (2001), 18 U.S.C.A. § 2332e (2001)). 2. There is disagreement as to whether an act of terrorism by a foreign national is a crime or an act of war against the United States (Dunlap, C. (2002). International law and terrorism. Army Lawyer, 2002(23)). Unit 3: Crimes against Property (2 weeks) Objectives: CLP.3.1 Describe the difference between laws dealing with crimes against real property and crimes against personal property. Content: 1. Crimes against real property are crimes committed against a structure or land and include: a. Arson, which is defined as the burning of a dwelling structure or building and requires a burning Va. Code §18.2-77 (1997), Va. Code §18.2-80 (1981) and Schwartz v. Com., 41 Va. App. 61 (Va. Ct. App. 2003)). b. Burglary, which is defined as the breaking and entering a dwelling house of another in the nighttime with intent to commit a felony or any larceny, and actual breaking involves the application of some force, slight though it may be whereby the entrance occurs (Va. Code 18.289 (1975) and Bright v. Com., 4 Va. App. 248 (Va. Ct. App. 1987)). c. Criminal Trespass, which is defined as when a person without authority of law goes upon or remains upon the lands, buildings or premises of another, or any portion or area thereof, after having been forbidden to do so (Va. Code §18.2-119 (2011) and Pleasants v. Com., 214 Va. 646 (Va. 1974)). 2. Crimes against personal property are committed against a person’s material goods and includes: a. Larceny, which is defined as the wrongful or fraudulent taking of personal goods of some intrinsic value, belonging to another, without his assent, and with the intention to deprive the owner thereof permanently, and requires an actual taking, or severance of the goods from the possession of the owner (Bruhn v. Com., 35 Va. App. 339 (Va. Ct. Ap.. 2001)). Larceny in Virginia is broken into two sub-categories: i. Grand larceny, when a person commits (i) larceny from the person of another of money or other thing of value of $5 or more, (ii) commits simple larceny not from the person of another of goods and chattels of the value of $200 or more, or (iii) commits simple larceny of any firearm, regardless of the firearm's value (Va. Code §18.2-95 (1998)), and ii. Simple larceny, when a person (i) commits larceny from the person of another of money or other thing of value of less than $5, or (2) commits simple larceny not from the person of another of goods and chattels of the value of less than $200, except as set forth for in the grand larceny definition Va. Code §18.2-95 (1998). b. Embezzlement, which is defined as when a person wrongfully and fraudulently uses, disposes of, conceals or embezzles any money, valued paper, or any personal property, tangible or intangible, which he received for another person in trust or as part of his employment (Va. Code §18.2-111 (2003) and Dove .v .Com., 41 Va. App. 571 (Va. Ct. Ap.. 2003)). CLP.3.2 Account for increasing computer and electronic based crimes. Content: 1. Computer based crimes include the following: a. Sending spam emails in a way to conceal the identity of the sender (VA. Code § 18.2-152.3:1 (2010)). b. Computer trespass including changing or destroying information, disabling or making a computer malfunction, altering financial information, causing physical injury via computer, making unauthorized copies, installing keystroke copying information, and installing programs to take over control of a computer (Va. Code §18.2-152.4 (2007)), c. Invasion of privacy, i.e., intentionally examining without authority any employment, salary, credit or any other financial or identifying information (Va. Code §18.2-152.5 (2005)), and d. Harassment of another person by computer (Va. Code §18.2-152.7:1 (2000)). 2. It is illegal to use certain electronic devices to commit criminal activity, i.e., cheating at a casino (N.R.S. §465.075 (2011) and N.R.S. § 465.083 (1981)). Unit 4: Crimes against society (3 weeks) Objectives: CLP.4.1 Describe laws against fraud. Content: Criminal fraud is deceitful conduct designed to manipulate another person to give up something of value to another person and includes: 1. Lying to gain something of value (Office of the insurance fraud prosecutor charges 11, including three chiropractors, in alleged schemes involving the illegal use of runners to recruit accident victims as patients. (2011, July 27). Retrieved from http://www.nj.gov/oag/newsreleases11/pr20110727a)). 2. False pretenses, e.g., repeating something that is or ought to have been known by the fraudulent party as false or suspect (Wynne v. Com, 18 Va. App. 459 (Va. Ct. App. (1994)), or 3. Concealing a fact from the other party which may have saved that party from being cheated Sweat v. Com. 2010 WL 3218614 (Va. Ct. App. 2010)). 4. Forgery, e.g., creating a false signature (Dillard v Com., 32 Va. App. 515 (Va. Ct. App. 2000)), and 5. Identity theft, e.g., stealing another person’s personal information to commit other crimes (Gheorghiu v. Com., 280 Va. 678 (Va. 2010)). CLP.4.2 Compare criminal health and safety laws with morality laws. Content: 1. Laws protecting health and safety, which criminalize unhealthy or unsafe activity, include: a. Illegal drug laws (Clayton, C. (2010, December 08). Virginia crime panel calls for ban of synthetic marijuana. Retrieved from http://hamptonroads.com/2010/12/virginia-crime-panelcalls-ban-synthetic-marijuana), and b. Underage sale and consumption of alcohol laws (Va. Code. §4.1-304 (1993), VA Code §46.2347(1989), and Mejia v. Com., 23 Va. App. 173 (Va. Ct. App. 1996)). 2. Morality crimes, which criminalize immoral or corrupt activities, include illegal gambling (Op. Va. Atty. Gen. 10-095 (2010)) (http://www.oag.state.va.us/Opinions%20and%20Legal%20Resources/Opinions/2010opns/October10op nndx.html and then opinion 10-095). CLP.4.3 Examine laws protecting peace and order. Content: 1. Laws protecting peace and order are most often categorized as disorderly conduct offenses and include: a. Public intoxication (being under the influence of drugs or alcohol in public) (McGhee v. Com., 280 Va. 620 (Va. 2010)), b. Using profane language in public (Ross, C. (2008, July 23). Profanity charge dismissed against 'boots' riley in norfolk. Retrieved from http://hamptonroads.com/2008/07/profanity-chargedismissed-against-boots-riley-norfolk, and c. Causing or being part of a Riot (and Harrell v. Com., 11 Va. App. 1 (Va. Ct. App. 1990)). Unit 3: Criminal Procedure I: “Cops and Robbers.” (9 weeks) Objectives: CLP.5.1 Describe the roots and processes of search and seizure. Content: 1. What constitutes a search? a. The scope of the Fourth Amendment includes the compulsory production of a person’s papers to be used against him in a criminal court (Boyd v. U.S., 116 U.S. 616 (1886)). b. The Fourth Amendment protects people, not places, and a physical intrusion into an area occupied by a suspect is not required under the Fourth Amendment (Katz v. U.S., 389 U.S. 347 (1967)). c. There is both a subjective and objective test of reasonableness for protected searches. The subjective test requires the plaintiff to genuinely expect privacy, and the objective test requires that, given the circumstances, a reasonable person in a similar situation also would have expected privacy (U.S. v. Padron, 657 F. Supp. 840 (D. Del. 1987)). d. Specific examples defining the limits of a search: i. When a suspect consents to speak to another person who is not a police officer, i.e., the false friend technique (U.S. v. White, 401 U.S. 745 (1971)). ii. When the search occurs in an open field (U.S. v. Pinter, 984 F. 2d 376 (10th Cir. 1993)). iii. When the search occurs on a property but not in a building, i.e., curtilege (U.S. v. Dunn, 480 U.S. 294 (1987)) iv. When new technology is being use such as: - Electronic tracking devices (U.S. v. Jones, --- US --- (2012)) - FLEAR technology (Kyllo v. U.S., 533 U.S. 27 (2001)) v. When the police conduct aerial surveillance (Ciraolo v. CA, 476 U.S. 207 (1985)) vi. When dogs are used to sniff out scents (U.S. v. Place, 462 U.S. 696 (1983)) vii. When the police search a suspect’s garbage (CA v. Greenwood, 486 U.S. 35 (1988)). 2. What constitutes a seizure (reasonableness)? a. There is no seizure if a reasonable person believes she is free to leave. A person is seized when, in light of the circumstances, a reasonable person would have believed that she was no longer free to leave (U.S. v. Mendenhall, 446 U.S. 544 (1980)). b. An officer acting on more than a “hunch” in a situation where “a reasonably prudent man would have been warranted in believing a suspect was armed and thus presented a threat to the officer's safety” did not violate the Fourth Amendment in investigating defendant’s suspicious behavior (Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1967)). c. When deciding if a search request is overly coercive within a confined space (such as a bus), the issue is not whether a party felt “free to leave,” but whether a party felt free to decline or terminate the search encounter (Florida v. Bostick, , 501 U.S. 429 (1991)). d. To constitute a seizure of the person there must be either the application of physical force, however slight, or, where that is absent, submission to an officer's “show of authority” to restrain the subject's liberty (CA v. Hodari D, 499 U.S. 621 (1991)). CLP.5.2 Describe the purpose and requirements of probable cause. Content: 1. There is both an objective standard and a balancing test to determine probable cause (Whren v. U.S., 517 U.S. 806 (1996)). a. An objective standard is used to determine if probable cause exists in a criminal case, i.e., if an actual traffic violation occurred, the ensuing search and seizure of the offending vehicle was reasonable, regardless of what other personal motivations the officers might have had for stopping the vehicle. b. The balancing test is between a search-and-seizure's benefits and the harm it might cause to the individual, but only in cases of unusually harmful searches and seizures. 2. The standard for determining probable cause based on informant information is the “totality of the circumstances” standard, i.e., an informant's veracity, reliability, and basis of knowledge are important in determining probable cause, but that those issues are intertwined and not rigidly applied (Ill v. Gates, 462 U.S. 213(1983)). CLP.5.3 Describe the purpose, effects, and limits of the exclusionary rule. Content: 1. Evidence obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment cannot be used in a criminal proceeding against the victim of the illegal search and seizure (U.S. v. Calandra, 414 U.S. 338 (1974)). a. The purpose of the rule is to deter future unlawful conduct by law enforcement (Calandra, supra). b. The rule is limited in scope (Calandra, supra) i. Applied only to areas where “its remedial objectives” are best served. ii. Can only be argued when the government seeks to use evidence to incriminate the victim of an unlawful search. 2. There are limits to the use of the exclusionary rule, which include: a. The good faith exception where a police officer honestly relies on a defective search warrant (U.S. v. Leon, 468 U.S. 897 (1984)), and b. The “fruit of the poisonous tree” doctrine, which states that there are three exceptions to this doctrine (Wong Sun v. U.S. 371 U.S. 471 (1963)): i. The police would find the evidence anyway from an independent source ii. The police would have inevitably discovered the evidence, or iii. The evidence was obtained in violation of the law but the suspect then after a reasonable amount of crime made voluntary statements regarding the evidence thus purging the taint. CLP.5.4 Describe the requirements to obtain a warrant. Content: 1. The Constitution requires that police officers obtain a warrant prior to a search (U.S. Const. Amend. IV) 2. The requirements for obtaining and executing a warrant include: a. A neutral magistrate must issue the warrant (Shadwick v. City of Tampa, 407 U.S. 345 (1972)). b. The warrant cannot be supported by purposefully made or reckless false statements (Franks v. DE, 438 U.S. 154 (1978)). c. The warrant must set forth specific information (particularity) of the search including (Groh v. Ramirez, 540 U.S. 551 (2004)): i. Time and place for executing the warrant, and ii. The items to be seized under the warrant. 3. The police must normally “knock and announce” their presence before executing a search warrant requirements for executing a warrant (Wilson v. Arkansas, 514 U.S. 927 (1995)). a. When evidence may be destroyed there is no need for making police officers knock and announce their presence (Richards v. Wisconsin, 520 U.S. 385 (1997)) b. The Knock and Announce warrant requirement is being abandoned in many states (U.S. v. Sutton, 336 F.3d 550 (7th Cir. 2003)) 4. The police do not need a warrant under the following circumstances: a. When the police take blood from a suspect after an arrest to conduct a blood alcohol test (Schmerber v. California, 384 U.S. 757 (1966)). b. When the police are in “hot pursuit” of a suspect (Warden v. Hayden, 387 U.S. 294 (1967)) c. When evidence is in plain view of a police officer who is in a room lawfully (Arizona v. Hicks, 480 US. 321 (1987)). d. The police may search a vehicle but only if there is a possibility that the officer may be in danger during the stop (Arizona v. Gant, 556 U.S. 332 (2009)). e. Search and seizure rules may be relaxed, but only to an extent, in certain institutions like schools (Stafford Unified School Dist. V. Redding, 557 U.S. 364 (2009)). CLP.5.5 Describe arrest requirements and procedures. Content: 1. For a seizure of a person to be considered an arrest two elements must be met (Yam Sang Kwai v. INS, 411 F. 2d. 683 (D.C. Cir. 1969)): a. The person being seized knows that his freedom of movement is curtailed for an indefinite period of time, and b. The actions of the police officer when seizing a person are based on probable cause. 2. There are three general rules regarding arrest. a. An officer may arrest a person in a public place without a warrant, even if it is practicable to secure one (U.S. v. Goddard, 312 F.3d 1360 (11th Cir. 2002)). b. No person may be arrested in his home without an arrest warrant, absent exigent circumstances or valid consent (Payton v. New York, 445 U.S. 573, (1980)). c. Absent exigent circumstances or valid consent, officer may not arrest a person in another person’s home without a search and perhaps an arrest warrant (Steagald v. U.S., 451 U.S. 204 (1981)). 3. There are three primary exigent circumstances regarding a search incident to an arrest a. Evidence will be destroyed (U.S. v. Harvey, 205 F. Supp. 2d 546 (E.D. Va. 2002)) b. Suspect will escape (U.S. v. Clement, 854 F.2d 1116 (8th Cir. 1988)), and c. Harm will result to others (O’Donnell v. Brown, 335 F. Supp. 2d 787 (W.D. Mich. 2004)). 4. Searches that are incident to arrest include: a. Contemporaneous searches during a full custodial arrest (U.S. v. Powell, 483 F. 3d 836 (D.C. Cir. 2007)) b. Automobile searches in the area accessible to the arrestee (U.S. v. McNab, 775 F. Supp. 1 (D. D.C. 1991)), and c. Protective sweeps in areas accessible to the arrestee (U.S. v. Walker, 474 F. 3d 1249 (10th Cir. 2007)). CLP.5.6 Evaluate the concept of reasonableness with regard to search and seizure by law enforcement. Content: 1. There are five instances where the reasonableness of the officer’s actions come into play a. Whether a police officer demonstrates reasonable suspicion under the totality of the circumstances when making a stop and frisk seizure (Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968)), b. Whether an informant’s tip warrants an officer demonstrating reasonable suspicion under the totality of the circumstances (U.S. v. Elmore, 482 F. 3d 172 (2nd Cir. 2007)), c. Whether turning around prior to a roadblock is an “objective justification” that can form reasonable suspicion (U.S. v. Lester, 148 F. Supp. 2d 597 (D. Md. 2001)), d. Whether the withdrawal of consent by a suspect constitutes reasonable suspicion under the totality of the circumstances (U.S. v. Carter, 985 F. 2d 1085 (D.C. Cir. 1993)), and e. Whether the social contract allows for suspicionless searches in a particular instances, e.g., when a parole officer is searching a parolee’s home (Samson v. California, 547 U.S. 843 (2006)). CLP.5.7 Explain how and when self-incrimination protections are invoked. Content: 1. The 5th Amendment only protects a witness from being forced to make self-incriminating statement, not being forced to provide a sample of her voice (U.S. v. Dionisio, 410 U.S. 1 (1973)). 2. How and when is this right invoked? a. The right is invoked by the speaker when he or she is being required to say something that might incriminate them (Quinn v. U.S., 349 U.S. 155 (1955)). b. There are two instances when the right is automatically invoked i. During police interrogations (Oregon v. Elstad, 470 U.S. 298 (1985)), and ii. In cases where a speaker exercising his or her right would be penalized (Lefkowitz v. Cunningham, 431 U.S. 801 (1977)). 3. There are three issues that are specifically addressed under the Fifth Amendment (Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964)): a. Compulsion, i.e., forcing a speaker to speak b. Testimony, i.e., the speaker provides factual information regarding a case, and c. Incrimination, i.e., the factual information shines a guilty light on the speaker. CLP.5.8 Analyze the rationale behind the judicial decision in Miranda v. Arizona. Content: 1. The basic ruling (Miranda v. Arizona, 284 U.S. 436 (1966)). a. Any statements, whether exculpatory or inculpatory, obtained as a result of custodial interrogation may not be used against the suspect in criminal trial unless the prosecutor proves that the police provided procedural safeguards effective to secure the suspect’s privilege against compulsory self-incrimination. b. The rule applies to custodial interrogation, i.e., questioning initiated by law enforcement officers after a person has been taken into custody or otherwise deprived of his freedom of action in any significant way. c. Miranda requires reading of Supreme Court created warnings or alternative procedural safeguards that are just as or more effective. 2. Specific issues regarding Miranda: a. Meaning of custody under Miranda (Murray v. Earle, 405 F. 3d 278 (5th Cir. 2005)): i. There must be a formal arrest or ii. There must be a significant impairment of freedom based on an objective test based on the person being arrested. b. The Fifth Amendment applies only during an interrogation: i. An interrogation includes the functional equivalent of an interrogation (R.I. v. Innis, 446 U.S. 291 (1980)). ii. An interrogation does not include a custodial investigation by an undercover officer (Illinois v. Perkins, 496 U.S. 292 (1990)). iii. An interrogation does not include asking for a person’s name or age (Pennsylvania v. Muniz, 496 U.S. 582 (1990)). c. Miranda rights may be waived by a suspect when (Edwards v. Arizona, 451 U.S. 477 (1981)): i. The waiver is voluntary, and ii. The waiver constitute a knowing and intelligent relinquishment or abandonment of a known right or privilege, a matter which depends in each case “upon the particular facts and circumstances surrounding that case, including the background, experience, and conduct of the accused. d. What rights can suspects assert under Miranda (Fare v. Michael C., 442 U.S. 707 (1979)): i. The right to remain silent, and ii. The right to consult with an attorney. e. When are Miranda warnings not required to be stated? i. When public safety is at issue (New York v. Quarles, 467 U.S. 649 (1984)), and ii. During a suspect’s formal police booking if the questions asked during that booking are routine police procedures (U.S. v. Duarte, 160 F. 3d 80 (1st Cir. 1998)). 3. The reasonableness of Miranda has been recently questioned: a. A legislative attempt to overrule Miranda was overturned in United States v. Dickerson, but the reason why that occurred may not be about the validity of Miranda (Kamisar, Y. (2006). Miranda's reprieve. ABA Journal, Retrieved from http://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/mirandas_reprieve/). b. Miranda was recently limited in scope to allow for illegally seized evidence despite the fact that the evidence was obtained from a Fifth Amendment violation (U.S. v. Patane, 542 U.S. 630 (2004)). Unit 6: Criminal Procedure II: “Bail and Jail.” (9 weeks) Objectives: CLP.6.1 Describe post-arrest identification procedures and protections against misidentification. Content: 1. The police may not conduct a line-up that is unnecessarily suggestive and conducive to irreparable mistaken identification as to be a denial of due process (Foster v. California (394 U.S. 440 (1969)). 2. The police may use photographs to identify suspects so long as the manner in which the photographs are used does not lead to a significant chance of misidentification (U.S. v. Shannon, 424 F. 2d 476 (3rd Cir. 1970)). 3. The police may use a show up to identify suspects so long as the show up does not cause a substantial likelihood of irreparable misidentification under the totality of the circumstances (Sanchell v. Parratt, 530 F. 2d 286 (8th Cir. 1976)). CLP.6.2 Describe the requirements regarding setting bail and pre-trial detention of defendants. Content: 1. The 8th Amendment, as applied to both the federal government and the states, forbids the setting of excessive bail for defendants (U.S. v. Polouizzi, 697 F. Supp. 2d 381 (E.D.N.Y. 2010)). 2. Excessive bail is defined under the Eighth Amendment as bail set at a figure higher than an amount reasonably calculated to fulfill its purpose (Polouizzi, supra)). 3. Retraining movement as part of a release on bail may constitute excessive bail in violation of the Eighth Amendment (Polouizzi, supra)). CLP.6.3 Describe the requirements for creating an enforceable plea agreement. Content: 1. The parties may enter into a plea bargain; however, the prosecutor has almost ultimate control over charging pleas whereas the court has almost ultimate control over sentencing pleas (U.S. v. Miller, 722 F. 2d 562 (9th Cir. 1983)). 2. There are four requirements for creating a constitutionally valid plea bargain: a. The defendant must receive competent assistance of counsel during the plea bargaining process (Lafler v. Cooper, 2012 WL 932019 (2012)). b. The defendant’s plea must be made voluntarily and intelligently (Brady v. U.S., 397 U.S. 742 (1970)). c. Plea bargains are contractual in nature and both the prosecutor and defendant must honor the terms of the plea bargain (Petition of Geisser, 554 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1977)), and d. The defendant must make a statement regarding his or her culpability as part of a plea agreement (U.S. v. Tunning, 69 F. 3d 107 (6th Cir. 1995)): i. Pleas of guilty, nolo contendere (no contest), or an Alford plea (maintaining innocence yet accepting a plea bargain) are acceptable, ii. For an Alford plea (maintaining innocence) to be constitutional the court must be satisfied that there is strong factual evidence supporting the plea. 3. Culpable statements by the defendant during plea bargaining cannot be used against the defendant at trial (Moulder v. Indiana, 154 Ind. App. 248 (Ind. Ct. App. 1972)). CLP.6.4 Explain the due process requirements prior to and during a criminal trial. Content: 1. Defendants have a right to be advised of the charges against them prior to trial (Wilson v. Com., 31 Va. App. 495 (Va. Ct. App. 2000)). 2. In Virginia defendants do not have a right to have their case heard before a grand jury (Wilson v. Com., supra)). 3. In Virginia a defendant has the right to a probable cause hearing to see if the police have enough evidence to actually arrest the defendant (Moore v. Com., 218 U.S. 388 (1977)). 4. No defendant should be put in double jeopardy for the same criminal offense or punishment, i.e., the offense or punishment have the same elements (U.S. v. Dixon, 509 U.S. 688 (1993)). CLP.6.5 Compare the federal and state rights to a speedy trial. Content: 1. The federal right to a speedy trial requires that four factors (Barker factors) be reviewed and balanced against each to determine is a defendant’s right to a speedy trial was violated, to wit: (1) the length of the delay; (2) the invocation of the right; (3) the prejudice to the defendant, and (4) the reasons for the delay (U.S. v. Khalfan, 751 F. Supp. 2d. 515 (S.D.N.Y. 2010). 2. Virginia extends that right by requiring all trials to commence within five months of a judicial finding of probable cause in district court and nine months for a probable cause finding in circuit court (Va. Code §19.2-243 (2009)). 3. The right to a speedy trial may be claimed or waived (Stevens v. Com., 225 Va. 224 (1983)). CLP.6.6 Examine issues related to the defendant’s right to counsel. Content: 1. Under the Sixth Amendment the defendant has a right to counsel: a. At trial (Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963)) b. On appeal (McClure v. Oregon State Bd. of Parole (900 F. 2d 263 (9th Cir. 1990) (unpublished opinion)), and c. At a critical stage of trial (U.S. v. Wade, 388 U.S. 218 (1967)). 2. There are many remedies to remedy ineffective assistance of counsel during a criminal trial (U.S. v. White, 371 F. Supp. 2d 378 (W.D. N.Y. 2005)). 3. Defendants who wish to represent themselves must knowingly and voluntarily waive their right to counsel (U.S. v. England, 507 F. 3d 581 (7th Cir. 2007)). CLP.6.7 Explain the essential components of a defendant’s right to a jury trial. Content: 1. Defendants have a right to a jury trial in serious criminal cases, i.e., felony trials (Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145 (1968)). 2. To obtain a valid guilty verdict a jury must convict a defendant “beyond a reasonable doubt” (Johnson v. Louisiana, 406 U.S. 356 (1972)). 3. Nine of twelve jurors agreeing for a conviction constitute a defendant being convicted “beyond a reasonable doubt” for Fourth Amendment purposes (Johnson, supra)). CLP.6.8 Evaluate issues regarding the punishment of convicted offenders. Content: 1. The 8th Amendment “prohibits the imposition of inherently barbaric punishments under all circumstances “(Graham v. Florida, --- U.S. ---, 130 S. Ct. 2011 (2010)): a. Physical punishments such as torture are considered cruel and unusual punishment (Graham, supra)). b. Punishments that are not “graduated and proportioned to [the] offense” are considered cruel and unusual punishment (Graham, supra)). 2. Use of the death penalty is not cruel and unusual punishment so long as there is not an objectively intolerant risk of harm such as unnecessary pain to the convict (Baze v. Rees, 553 U.S. 35 (2008)). CLP.6.9 Describe laws pertaining to the effective administration of justice. Content: 1. Perjury is when any person to whom an oath is lawfully administered on any occasion willfully swears falsely on such occasion touching any material matter or thing (Va. Code §18.2-434 (2005)): a. In Virginia the Commonwealth must prove that: “(1) that an oath was lawfully administered; (2) that the defendant willfully swore falsely; and (3) that the facts to which he falsely swore were material to a proper matter of inquiry.” (Fritter v. Com., 45 Va. App. 345 (Va. App. 2005)). b. In Virginia there must be two corroborating witnesses to the uttering of perjured testimony (Keffer v. Com., 12 Va. App. 545 (Va. App. 1991)). 2. Obstruction of Justice is when a person without just cause knowingly obstructs a criminal or civil action (Va. Code §18.2-460 (2009)). a. Acts clearly demonstrating an intention on the part of the accused to prevent the officer from performing his duty, as to ‘obstruct’ ordinarily implies opposition or resistance by direct action and forcible or threatened means, but an actual assault on the officer is not necessary (Smith v. Tolley, 960 F. Supp. 997 (E.D.Va. 1997)). b. Peaceful verbal criticism of a police officer who is making an arrest is protected by the First Amendment and is not obstruction of justice (Wilson v. Kittoe, 337 F.3d 392 (4th Cir. 2003)). 3. Bribery is when a person, with intent to influence the performance of any act related to the employment or function of any public officer, public employee or juror, promises or tenders to that person any property or personal advantage which he is not authorized by law to accept, and includes the giving of a bribe, the offer of a bribe and the promise of a bribe (Va. Code §18.2-438 (1978) and Ford v. Com., 177 Va. 889 (Va. 1941)).