kafka-2 - WordPress.com

advertisement

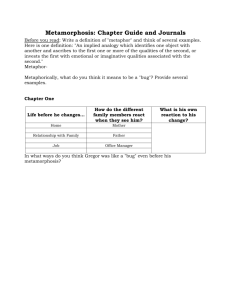

The Metamorphosis Franz Kafka Franz Kafka • 1883-1924 • Born in Prague (in what is now the Czech Republic) • Spoke and wrote in German • Had a doctorate in law, but worked in the insurance industry 2 Franz Kafka • Kafka’s writings often deal with loneliness, isolation, and alienation, all of which are aggravated by the social and economic systems that structure human relations. • His style is stark – in spite of the strange subject matter in many of his works, there is no poetic or metaphoric language. • The Metamorphosis (written in 1912, published in 1915) is probably his most famous work. 3 Franz Kafka • Generically, The Metamorphosis is a novella – a text that is longer than a short story but not as long as a novel. • Heart of Darkness, which we will be looking at in the second term, falls under the same category. 4 Setting the Scene • The protagonist of the story is Gregor Samsa, who is the son of middle-class parents in Prague. • Gregor’s father lost most of his money about five years earlier, causing Gregor to take a job with one of his father's creditors as a travelling salesman. • Gregor provides the sole support for his family (father, mother, and sister), and also found them their current lodgings in Prague. • When the story begins, Gregor is spending a night at home before embarking upon another business trip. And then. . . 5 Part I: A Famous Opening Line • “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a giant insect” (958). • Compare with another famous opening line . . . 6 Part I: A Famous Opening Line • “It was a bright cold day in April and the clocks were striking thirteen” (Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four 1). • What do these two lines have in common? 7 Compare the beginnings to the endings: • “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a giant insect” (958). • “It was a bright cold day in April and the clocks were striking thirteen” (Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four 1). 8 Both sentences make their points through defamiliarization: • They initially describe normal, everyday, almost boring events, only to disrupt this sense of normalcy at the very end. • The disruption of readerly expectation is sometimes called a defamiliarization effect – in German, Verfremdungseffekt, which translates as “alienation effect.” This term is associated with the German playwright Bertolt Brecht. 9 Lost in Translation? • English translators have often sought to render the word Ungeziefer as “insect,” but this is not entirely accurate, as, in German, Ungeziefer literally means “vermin” and is sometimes used colloquially to mean "bug,“ which is a much more vague term than “insect.” • Why might “vermin” actually be more appropriate? 10 Lost in Translation? • “Vermin” can either be defined as a parasite feeding off the living (as is Gregor's family feeding off him), or a vulnerable entity that scurries away upon another’s approach, as Gregor does for most of the narrative after his transformation. 11 Vladimir Nabokov's Drawings 12 Significance • As with “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” improbable or even impossible events in fiction often ask us to consider what the larger meaning of these events may be. • By disrupting our normal perspective on reality, these unusual plotlines force us to ask profound questions. 13 Significance • Writers often use fantastic events to signify additional levels of meaning beyond the literal. • Thus, we need to ask ourselves what Gregor’s metamorphosis signifies in terms of larger issues. 14 At first, Gregor refuses to accept his changed state: • He tries to get out of bed, get dressed, plan his day, and so on, as though his metamorphosis hadn’t actually happened. • The long, detailed description of the difficulties of getting out of bed (960-62) reminds us of how dependent we are on our bodies. Gregor’s normal sense of corporeality – of himself – is thus disrupted, or defamiliarized. 15 His Parents and the Clerk • Gregor, still trapped in his room, hears the arrival of the chief clerk from his employer, who threatens him. • Nabokov, in his lecture on the novella, notes that the conversation in the hallway “is a little on the lines of a Greek chorus,” with all parties making demands upon Gregor. 16 His Parents and the Clerk • When Gregor finally escapes from his room, his appearance so horrifies all onlookers (the chief clerk runs away, and his mother screams and upsets a pot of coffee) that his father beats him back into the chamber, making him bleed in the process. 17 His Parents and the Clerk • So, Gregor goes full circle: he is imprisoned in his body, and he is once again imprisoned in his room. • Thus ends Part I of the novella. 18 Part II: Gregor’s Family • In Part II, we learn much more about Gregor’s parents and sister, and their responses to the transformed situation in their household. • We experience all of this from Gregor’s perspective, as he listens to his family through the door of his room. 19 Part II: Gregor’s Family • Our access to his family, then, is, like Gregor’s, limited, and filtered through his perspective. • What happens to Gregor during this sequence? 20 Part II: Gregor’s Family • At the beginning of Part II, an attempt is made to feed Gregor, but the human food that has been placed in his room by his sister (bread and milk) is wholly unappealing. • Disappointed, Gregor spends the remainder of the long evening trying to hear his family in the living room. 21 Part II: Gregor’s Family • He cannot hear much, however, and notes “‛What a quiet life our family has been leading,’ [. . .] and as he sat there motionless staring into the darkness he felt great pride in the fact that he had been able to provide such a life for his parents and sister in such a fine flat. But what if all the quiet, the comfort, the contentment were now to end in horror?” (970). • What “horror” is Gregor referring to? 22 Part II: Gregor’s Family • Although the narrative goes on to note that “[t]o keep himself from being lost in such thoughts, Gregor took refuge in movement and crawled up and down in the room,” neither Gregor nor his family seem particularly horrified by his transformation. • The horror that Gregor suggests appears to be poverty – the loss of the respectability and comfort that his job provided. 23 Part II: Gregor’s Family • Note that, as he hears his family steal up the stairs to go to bed, Gregor starts to feel uneasy, and “with a half-unconscious action, not without a slight feeling of shame, he scuttled under the sofa, where he felt comfortable at once, although his back was a little cramped and he could not lift his head up, and his only regret was that his body was too broad to get the whole of it under the sofa . . .” 24 Part II: Gregor’s Family • “He stayed there all night, spending the time partly in a light slumber, from which his hunger kept waking him up with a start, and partly worrying and sketching vague hopes, which all led to the same conclusion, that he must lie low for the present and, by exercising patience and the utmost consideration, help the family to bear the inconvenience that he was bound to cause them in his present condition” (970). 25 Part II: Gregor’s Family • Gregor’s concern is for his family, and not for himself. Are they equally concerned with him? • At first, they seem to be. Gregor’s sister Grete brings him a selection of foods (he chooses the ones that have rotted), and he is pathetically grateful. Note, though, what happens when she returns to the room . . . 26 Part II: Gregor’s Family • “[H]is sister turned the key slowly as a sign for him to retreat. That roused him at once, although he was nearly asleep, and he hurried under the sofa again. But it took considerable self-control for him to stay under the sofa, even for the short time his sister was in the room, since the large meal had swollen his body somewhat and he was so cramped he could hardly breathe. . .” 27 Part II: Gregor’s Family • “Slight attacks of breathlessness afflicted him and his eyes were starting a little out of his head as he watched his unsuspecting sister sweeping together with a broom not the remains of what he had eaten but even the things he had not touched, as if these were now of no use to anyone, and hastily shovelling it all into a bucket, which she covered with a wooden lid and carried away” (971). • What is the significance of this passage? 28 Part II: Gregor’s Family • In the first few days following Gregor’s metamorphosis, almost all conversation centres around him and what the family will do now. • We are told that, when Gregor began working for his exploitative firm in an effort to save his family’s fortunes, he was soon “earn[ing] so much money that he was able to meet the expenses of the whole household and did so. They had simply got used to it, both the family and Gregor” (973). 29 Part II: Gregor’s Family • “With his sister alone had he remained intimate, and it was a secret plan of his that she, who loved music, unlike himself, and could play movingly on the violin, should be sent next year to study at the School of Music, despite the great expense that would entail, which must be made up in some other way” (973). • Gregor had intended to announce this decision on Christmas Day. 30 Part II: Gregor’s Family • Gregor, knowing that he can do nothing to help the family now, keeps thinking about this situation, and wondering what his family will do. • What does he hear his father telling the rest of the family about their financial situation? 31 Part II: Gregor’s Family • “[A] certain amount of investments, a very small amount it was true, had survived the wreck of their fortunes and had even increased a little because the dividends had not been touched meanwhile. And besides that, the money Gregor brought home every month—had never been quite used up and now amounted to a small capital sum. Behind the door Gregor nodded his head eagerly, rejoiced at his evidence of unexpected thrift and foresight. True, he could really have paid off some more of his father's debts to the boss with this extra money, and so brought much nearer the day on which he could quit his job, but doubtless it was better the way his father had arranged it” (973-74). 32 Part II: Gregor’s Family • What strikes you as significant in this passage? • Gregor’s family have been living off his earnings while he slaves away at a job that he hates, and, as the description that follows suggests, their behaviour seems particularly parasitic given how clearly unprepared they are to work: 33 Part II: Gregor’s Family • “Now, his father was still hale enough but an old man, and he had done no work for the past five years and could not be expected to do much; during these five years, the first years of leisure in his laborious though unsuccessful life, he had grown rather fat and become sluggish . . .” 34 Part II: Gregor’s Family • “And Gregor’s old mother, how was she to earn a living with her asthma, which troubled her even when she walked through the flat and kept her lying on a sofa every other day panting for breath beside an open window? . . .” 35 Part II: Gregor’s Family • “And was his sister to earn her bread, she who was still a child of seventeen and whose life hitherto had been so pleasant, consisting as it did in dressing herself nicely, sleeping long, helping in the housekeeping, going out to a few modest entertainments and above all playing the violin?” (974). 36 Part II: Gregor’s Family • There is a certain amount of irony in the narrative voice here – while Gregor feels a great deal of shame for the perilous situation in which he believes that he has left his family, there’s a clear implication here that it is they who are to blame. 37 Part II: Gregor’s Family • When Gregor’s sister enters his room one morning about a month after his metamorphosis, she seems ill at ease – as a result, Gregor spends four hours dragging a sheet to the sofa so that he can hide behind it and not be seen, even though this is not very comfortable for him (975). 38 Part II: Gregor’s Family • His parents stay out of the room, but eventually, Gregor’s mother enters. • His sister suggests that, if they were to take the furniture out of his room, Gregor would have more space in which to crawl about. • Gregor’s mother, however, is not convinced, believing that taking the furniture away might be read as a sign that the family has given up all hope (977). 39 Part II: Gregor’s Family • Note the extended passage on page 977, which shows Gregor as being torn between two emotions, but ultimately concluding that he wants the furniture to stay. Grete, however, thinks otherwise, and the two women soon begin removing the furniture. 40 Part II: Gregor’s Family • “Although Gregor kept reassuring himself that nothing out of the way was happening, but only a few bits of furniture were being changed round, he [. . .] was bound to confess that he could not be able to stand it for long. They were clearing his room out; taking away everything he loved” (978). 41 Part II: Gregor’s Family • Gregor decides that he must at least save the picture on the wall, and so attaches himself to it, but his mother faints at the sight of him, and, concerned for his mother, Gregor is outside of his room when his father demands to know what has been happening. 42 Part II: Gregor’s Family • What follows is one of the most important scenes in the story. • First of all, Gregor’s father has changed: “Truly, this was not the father he had imagined to himself [. . .] and yet, could that be his father? the man who used to lie wearily sunk in bed [. . . w]as standing there in fine shape; dressed in a smart blue uniform with gold buttons such as bank messengers wear; his strong double chin bulged over the stiff high collar of his jacket . . .” 43 Part II: Gregor’s Family • “from underneath his bushy eyebrows his black eyes darted fresh and penetrating glances; his onetime tangled white hair had been combed flat on either side of a shining and carefully exact parting. He pitched his cap [. . .] in a wide sweep across the whole room on to a sofa and with the tailends of his jacket thrown back, his hands in his trouser pockets, advanced with a grim visage towards Gregor. [. . .] Gregor was dumbfounded at the enormous size of his shoe soles” (980). 44 Part II: Gregor’s Family • Gregor’s father does not actually stomp on Gregor, but he does pelt him with apples while his son is trying to escape, hurting him tremendously. • At the end of Part II, Gregor loses consciousness just as he sees his mother “with her hands clasped round his father’s neck as she begged for her son’s life” (981). 45 Part II: Gregor’s Family • At this point, how does each member of Gregor’s family feel about him? 46 Part II: Gregor’s Family • Gregor’s sister has become openly hostile towards the brother she once loved. • Gregor’s mother still appears to have some love for him, but she is very much struggling to adjust to his present form, and this struggle is taking its toll on her health. • Gregor’s father has become strong (after five years of being completely supported by Gregor), and is not afraid to use his new power against his son. 47 Part III: Decline and Death • “The serious injury done to Gregor, which disabled him for more than a month—the apple went on sticking in his body as a visible reminder, since no one ventured to remove it—seemed to have made even his father recollect that Gregor was a member of the family, despite his present unfortunate and repulsive shape, and ought not to be treated as an enemy, that, on the contrary, family duty required the suppression of disgust and the exercise of patience, nothing but patience” (981). 48 Part III: Decline and Death • The door leading from Gregor's darkened room to the lighted living room is now left open every evening, but when Gregor creeps out to listen to his family’s conversations, they sound glum, tired, and defeated (981-82). • The serving-girl is dismissed (replaced with an elderly charwoman, who becomes important later on), and “[v]arious family ornaments, which his mother and sister used to wear with pride at parties and celebrations, had to be sold” (982). 49 Part III: Decline and Death • “But what they lamented most was the fact that they could not leave the flat which was much too big for their present circumstances, because they could not think of any way to shift Gregor. Yet Gregor saw well enough that consideration for him was not the main difficulty preventing the removal, for they could have easily shifted him in some suitable box with a few air holes in it; what really kept them from moving into another flat was rather their own complete hopelessness and the belief that they had been singled out for a misfortune such as had never happened to any of their relations or acquaintances” (982-83). 50 Part III: Decline and Death • The family feels persecuted, and Gregor, consequently, is increasingly neglected. • The half-hearted cleaning of his room by his mother, after weeks of sisterly neglect, causes a noisy family row, with the result that the charwoman takes over his care. She is not frightened of him, and, in fact, seems to have some friendliness towards him, referring to Gregor as “you old dung beetle” (984). 51 Part III: Decline and Death • Nevertheless, Gregor’s room becomes filled with spare furniture and various items haphazardly placed there by his family, as one of the rooms in the flat has been let to lodgers. • Notice that Gregor almost stops eating entirely, while Kafka emphasizes the food being prepared and eaten by the “[t]hree serious gentlemen” (985). 52 Part III: Decline and Death • “It seemed remarkable to Gregor that among the various noises coming from the table he could always distinguish the sound of their masticating teeth, as if this were a sign to Gregor that one needed teeth in order to eat, and that with toothless jaws even of the finest make one could do nothing. ‘I’m hungry enough,’ said Gregor sadly to himself, ‘but not for that kind of food. How these lodgers are stuffing themselves, and here am I dying of starvation!’” (985-86). 53 Part III: Decline and Death • In another crucial scene, Grete plays the violin in the kitchen, and Gregor is certain that this is the first time that he has heard the instrument since his metamorphosis. • The lodgers invite her to come into the living room, where they spend their evenings, in order to play for them. 54 Part III: Decline and Death • Gregor, “owing to the amount of dust which lay thick in his room and rose into the air at the slightest movement, [. . . is] covered with dust; fluff and hair and remnants of food trailed with him, caught on his back and along his sides; his indifference to everything was much too great for him to turn on his back and scrape himself clean on the carpet, as once he had done several times a day. And in spite of his condition, no shame deterred him from advancing a little over the spotless floor of the living room” (986). 55 Part III: Decline and Death • “To be sure, no one was aware of him. The family was entirely absorbed in the violin-playing; the lodgers, however, [. . .] had soon retreated to the window, [. . .] making it more than obvious that they had been disappointed in their expectation of hearing good or enjoyable violin-playing, that they had had more than enough of the performance and only out of courtesy suffered a continued disturbance of their peace” (986-87). 56 Part III: Decline and Death • Gregor, however, is certain that his sister is playing beautifully, and he “crawled a little farther forward and lowered his head to the ground so that it might be possible for his eyes to meet hers. Was he an animal that music had such an effect upon him? He felt as if the way were opening before him to the unknown nourishment he craved” (987). 57 Part III: Decline and Death • Gregor is responding on a very primitive level to the music, but there is something else going on as well: • “He was determined to push forward till he reached his sister, to pull at her skirt and so let her know that she was to come into his room with her violin, for no one here appreciated her playing as he would appreciate it. . .” 58 Part III: Decline and Death • “[H]is sister should need no constraint, she should stay with him of her own free will; she should sit beside him on the couch, bend down her ear to him and hear him confide that he had had the firm intention of sending her to the School of Music, and that, but for his mishap, last Christmas— surely Christmas was long past?—he would have announced it to everybody without allowing a single objection. After this confession his sister would be so touched that she would burst into tears, and Gregor would then raise himself to her shoulder and kiss her on the neck” (987). • What is the significance of this dream? 59 Part III: Decline and Death • Gregor’s vision is soon shattered when the lodgers spot him, and Gregor’s father, interestingly, tries to block the view of the lodgers and drive them towards their room. Unsurprisingly, the trio immediately gives notice to quit the flat. 60 Part III: Decline and Death • Gregor’s sister announces, with finality, that “things can’t go on like this. [. . .] I won’t utter my brother’s name in the presence of this creature, and so all I say is: we must try to get rid of it. We’ve tried to look after it and to put up with it as far as is humanly possible, and I don’t think anyone could reproach us in the slightest” (988). 61 Part III: Decline and Death • It does not take long for the father and sister to conclude that Gregor cannot understand them, and Grete insists that “[i]f this were Gregor, he would have realized long ago that human beings can’t live with such a creature and he’d have gone away on his own accord. Then we wouldn't have any brother, but we’d be able to go on living and keep his memory in honour. As it is, this creature persecutes us, drives away our lodgers, obviously wants the whole apartment to himself and would have us all sleep in the gutter” (989). • Painfully, Gregor makes his way back to his room, only to hear the door immediately being shut and bolted by his sister. 62 Part III: Decline and Death • “The rotting apple in his back and the inflamed area around it, all covered with soft dust, already hardly troubled him. He thought of his family with tenderness and love. The decision that he must disappear was one that he held to even more strongly than his sister, if that were possible. In this state of vacant and peaceful meditation he remained until the tower clock struck three in the morning. The first broadening of light in the world outside the window entered his consciousness once more. Then his head sank to the floor of its own accord and from his nostrils came the last faint flicker of his breath” (990). 63 Part III: Decline and Death • In the morning, the charwoman finds Gregor’s dead, dried-up body. • While Grete points out that Gregor must have starved to death, the family seems relieved, and Grete joins her family (invited by her mother “with a tremulous smile” [991]) without looking back. • The charwoman opens the window. It is the end of March, and thus the beginning of spring. 64 Part III: Decline and Death • Nabokov notes, in his famous lecture on this text, that after Gregor’s death it is never “father” and “mother” but only Mr. and Mrs. Samsa. • Mr. Samsa dismisses the lodgers in no uncertain terms – much to their surprise – “and as if a burden had been lifted from them [the family] went back into their apartment” (992). 65 Part III: Decline and Death • The family decides to “spend this day in resting and going for a stroll; they had not only deserved such a respite from work, but absolutely needed it” (992). • Should we read this passage in straightforward terms, or as tinged with irony? 66 Part III: Decline and Death • The charwoman reveals that the body has already been disposed of, and though this briefly unsettles the Samsas, they are soon unified again: • “[T]hey all three left the apartment together, which was more than they had done for months, and went by trolley into the open country outside the town. The trolley, in which they were the only passengers, was filled with warm sunshine. Leaning comfortably back in their seats they canvassed their prospects for the future, and it appeared on closer inspection that these were not at all bad, for the jobs they had got, which so far they had never really discussed with each other, were all three admirable and likely to lead to better things later on . . .” 67 Part III: Decline and Death • “The greatest immediate improvement in their condition would of course arise from moving to another house; they wanted to take a smaller and cheaper but also better situated and more easily run apartment than the one they had, which Gregor had selected. While they were thus conversing, it struck both Mr. and Mrs. Samsa, almost at the same moment, as they became aware of their daughter's increasing vivacity, that in spite of all the sorrow of recent times, which had made her cheeks pale, she had bloomed into a buxom girl. . .” 68 Part III: Decline and Death • “They grew quieter and half unconsciously exchanged glances of complete agreement, having come to the conclusion that it would soon be time to find a good husband for her. And it was like a confirmation of their new dreams and excellent intentions that at the end of their journey their daughter sprang to her feet first and stretched her young body” (993). 69 Part III: Decline and Death • How do you interpret the ending? What does it all mean? 70 Part III: Decline and Death • One can read this ending in a fairly straightforward manner – the story began with Gregor’s changed body, and it ends with Grete’s. • Now a “good-looking, shapely” woman, she is ready to be married off by her eager parents, who view her as a commodity to benefit them. 71 Part III: Decline and Death • Similarly, if we view the parents as parasitical, we might suggest that, now that they have wrung all of the life out of their son, they are ready to move on to their daughter – perhaps even to “eat” her! 72 Part III: Decline and Death • Gregor seems to have been by far the most caring and compassionate individual in the home. Now that he has gone, the fact that Grete is described more as animal than human being might cause us to wonder if there is any humanity left in the Samsas at all. 73