Social Media and Youth Voting at the Municipal Level in Calgary

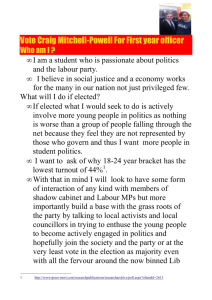

advertisement

Mobilising the youth vote through social media: young people and the 2015 British General Election Sarah PICKARD Université Sorbonne Nouvelle- Paris 3 Young people’s political participation in British general elections tends to be substantially lower than for other age groups. At present, 18-24 year-olds are mainly labelled in the media as being totally disaffected with traditional politics and politicians, leading to political abstinence or enthusiastic civil disobedience. Russell Brand who has strong media presence (including his recent book Revolution) is calling for an overhaul of the political system and encouraging the electorate to abstain from voting, in order not to endorse the status quo. Conversely, organisations such as Bite the Ballot are vigorously attempting to increase voter registration among young people. Meanwhile, the Scottish Parliament is endeavouring to enfranchise 16 to 17-year-olds in time for the 2015 General Election and the Labour Party leader, Ed Miliband, has made an electoral pledge to lower the voting age to include 1.5 million 16 to 17-year-olds if his party wins the General Election. It would seem that politicians are waking up to the importance of the youth vote after many years of concentrating on the ‘grey vote’. Social media is at the heart of political efforts to influence and attract young people. This paper explores the diverse forms of political communication through social media employed by the youth wings of traditional political parties in England: Conservative Future, Labour Students, Young Labour, Liberal Youth, Young Greens and Young Independence. It analyses the official website posts, Facebook messages and tweets from Twitter of youth wings, during the 6 months prior to the 7 May 2015 General Election. It examines quantitatively (frequency, authorship, actuality) and qualitatively (contents, message, objective) attempts to encourage voter registration among young people, to boost the youth vote, to convince young people to vote for them and lastly to persuade young people not to vote for other parties. Thus, this paper evaluates how information technology is being used to influence the youth vote in Britain in the run up to the 2015 General Election. 1 Mobilising the youth vote through social media: young people and the 2015 British General Election Young people’s political participation in British general elections tends to be substantially lower than for other age groups. Prior to the ay 2015 general election, 18-24 year-olds were often labelled in the media as being disaffected with traditional politics and politicians, leading to political abstinence. This was reinforced by Russell Brand - who has strong media presence - calling for an overhaul of the political system and abstention from voting, in order not to endorse the political status quo (Brand, 2014). Conversely, organisations such as the not-for-profit organisation Bite the Ballot (modelled on the American Rock the Vote) vigorously campaigned to increase registration and voting among young people. Meanwhile, the Scottish Parliament endeavoured to enfranchise 16 and 17-year-olds in time for the 2015 General Election. Votes for 16-17-year-olds already featured in the Liberal Democrats 2010 manifesto, and the Labour Party leader, Ed Miliband, announced in 2014 that Labour was in favour of lowering the voting age 16 and 17-yearolds if his party won the General Election.1 Young people are specifically affected by numerous issues, such as Educational Maintenance Allowance (EMA), higher education budgets, university tuition fees, youth unemployment, affordable accommodation and youth services. It would seem that politicians are waking up to the importance of the youth vote after many years of concentrating on the ‘grey vote’. Social media and new technologies have been at the heart of political efforts to influence and attract young people. Political parties usually have wings, also called youth factions (Rainsford, 2015), which are aimed at young people: Conservative Future, Labour Students, Young Labour, Liberal Youth, Young Greens and Young Independence. This article explores diverse forms of political communication through social media employed by the youth wings of traditional political parties in England. It analyses the official website posts, Facebook messages and Twitter tweets of youth wings, during the six months prior to the 7 May 2015 General Election. It examines quantitatively (frequency, authorship, actuality) and qualitatively (contents, message, objective) attempts to encourage voter registration among young people, to boost the youth vote, and to convince young people to vote for them rather than for another parties. Thus, through the prisme of youth wings, this article evaluates how information technology was used to influence the youth vote in Britain in the run up to the 2015 General Election. 2 Young people’s participation in traditional politics For many years, political participation was divided into two main forms. First, traditional, conventional or institutional participation, which includes registering on the electoral roll, voting in elections and being a member of a political party. Second, non-traditional, unconventional or noninstitutional participation, which includes protesting, dissenting and being involved in civil disobedience. This division was proferred by Marsh. Increasingly, a third kind of political participation is taken into account – xxx – which includes product boycotts. The media narrative prior to the 2015 general election regarding young people’s traditional political participation was overwhelmingly that British youth is politically apathetic and disinterested in politicians and politics (see, xxx), or disaffected due to the MPs expense scandal (see Pickard, 2013), or alienated (see Marsh). Such negative labelling is primarily due to the consistently lower rates of voter registration and voter turnout among young people; it corresponds to an overwhelmingly negative portrayel of young people (Pickard, 2014). (Martin, 2012; Pickard, 2016) Registration In order to vote in an election in Britain, it is necessary to be on the electoral roll or electoral register. Young people tend to have lower registration rates than other age groups. This phenomenon is partly because young people are more likely to be mobile, change addresses and live in temporary accommodation. It can also be explained by a will not to register – avoidance (Gallant, 2015), a lack of knowledge about how to register, or difficulty to register. Various efforts have been made in recent years to make inclusion on the electoral roll easier. First, ‘rolling registration’ or continuous registration was introduced by the Labour Government in February 2001 (Denver, 2012: 30; Pickard, 2005), so that it is now possible to be added to the electoral with a local authority throughout the year. Second, registration has been mandatory since 2001, as the head of household is obliged to list eligible voters in the household.2 Third, the gap between when registration closes and voting takes place has been narrowed. In 2015, the deadline to register was Monday 20 April, so 17 days before polling day, Thursday 7 May 2015.3 According to official figures for 2012, 70.2% of 20 to 24-year-olds were registered to vote, compared to more than 95% of people over 65 years-old (Electoral Commission, 2013). In the May 2015 general election, Xxxx of 18-24 year-olds were registered to vote (Electoral Commission, 2015). Therefore, xx% of this age group were registered to vote, xx percentage points lower than the population as a whole whose registration rate was xx% (see Table x). At the end of 2010, only 56% of 19-to-24 year olds were on the electoral register compared with 94% of those aged over 65 (Electoral Commission, 2011: 31). The age at which citizens become entitled to vote is 18, but the electoral registers also include records of ‘attainers’ – 16- and 17-year-olds who will turn 18 during the period in which the register is in force (Electoral Commission, 2011: 16). 3 Turnout Turnout rates of elections are calculated according the proportion of the population who vote that are actually registered to vote. Turnout rates exclude people who are not on the electoral roll.4 In other words, if someone is not on the electoral roll, he or she will not be included in the electoral turnout rate. As well as having lower registration rates than other age groups, young people’s turnout rates are smaller. Turnout rates in UK general elections consistently reveal a smaller proportion of young people than older people go to the polls (see Table x). According to David Denver, four interconnected social factors are associated with low turnout, being young (the most important), being unmarried, living in privately rented accommodation, and being residentially mobile (2012: 41). Crewe, Fox and Alt explain higher levels of non-voting by these groups in terms of isolation from personal and community networks, which are characteristic of stable communities and which encourage conformity or the norm of voting. Swaddle and Heath – cost and benefit. After an unprecedented low in 2001, participation rates among 18-24 year-olds increased in 2005 and 2010, but remained considerably lower than other age groups (see Table x). In 2015, xx% of 18 to 24-year-olds voted in the general election compared with 76% of people aged 65 and over (see Table x). Not voting can be equated with a lack of interest in traditional politics. It can also be a deliberate decision, which Nicole Gallant calls “voidance” (Gallant, 2015). Russell Brand advocated abstention in the 2015 general election, in order not to endorse the political system. A revolution (Brand, 2014). Russell Brand (May / October 2014): Don't bother voting. Stop voting stop pretending, wake up, be in reality now. Why vote? We know it's not going to make any difference. […] It is not that I am not voting out of apathy. I am not voting out of absolute indifference and weariness and exhaustion from the lies, treachery and deceit of the political class that has been going on for generations. But it can also be explained by the fact that young people may have other things to do, or the polling station might not be accessible enough, there is lack of opportunity to vote on line, via the Internet, with a Smartphone, etc. Lack of new technology. Electronic voting, voting on line, voting via a Smartphone was not possible in 2015. This is despite acknowledgements from the Electoral Commission and Electoral Reform Society. (Quotes). 4 The Digital Democracy Commission set up by the Speaker of the House of Commons, John Bercow, 2014 recommended in a report published in early 2015 that “By 2020, secure online voting should be an option for all voters” (Digital Democracy, 2015).5 The 2015 general election came eight months after the referendum on independence in Scotland that took place on 18 September 2014. Significantly, in this Scottish referendum, 16-17 year-olds were enfranchised for the first time in a British vote. Interest among 16 and 17 year-olds was considerable. Over 97%* of the Scottish population registered to vote. 109,533 16-17 year-olds registered to vote, about 80% of those eligible and the turnout was 84.6% (80%* for 16-17 yearolds). Nearly two thirds of young people want to be able to vote online in the general election, while a similar amount feels the current system is failing, new research shows. Prior to the 2015 general election, there were various campaigns and measures to encourage young people to register on the electoral roll and to vote. Initiatives to encourage young people to become engaged in politics include Smartphone apps, vlogging (video blogging) and social media campaigns aiming to transform how young people think about politics. Young wings and Youth factions Mainstream political parties all have young wings that are aimed at 18-30 year-olds, especially students (Lamb, 2002; Pickard, 2007; Tranmer, 2012): Conservative Party: Conservative Future; Green Party: Young Greens; Labour Party: Labour Students and Young Labour; Liberal Democrats: Liberal Youth; UK Independence Party (Ukip): Young Independence. It proves difficult to obtain official statistics. No political party youth wing responded to my request for membership figures. A certain amount competition among youth wings regarding membership numbers. According to the Young Greens website, (Young Greens, 2015) UKIP posted on its web page Twitter and Facebook provide a huge amount of political information and are becoming very important news sources, especially for young people. This means that they can be used to increase people’s political knowledge and interest. If politicians are serious about engaging young people in democracy, this is where they should be focusing their attention (Edwards, 2015: 169). “The decline in party affiliation is most stark for the young. In 1991, 29 per cent of fiteen-to twenty-four-year-olds supported a political party; in 2011 it was 15.8 per cent compared with 57.8 per cent of over-seventy-fives” (Gould, 2015: 49). This can partially be explained by the lifecycle effect, i.e. that people become more interested inpolitics as they become older. However, the 5 current rates – the gap between lower and higher age groups are much greater that in previous decades. PAGE, Ben (ed.). The Shock of the New? The menace of 2015. British Social Attitudes Survey, July 2014, p. 48, (https://www.ipsos-mori.com/Assets/Docs/News/ben-page-shock-of-the-new-ccn2014.pdf) Question: “Do you think of yourself as a supporter of any one political party?” Prewar (born before 1945) = 56% Baby boomers (born 1945-1965) = 40% Generation X (born 1966-1979) = 30% Generation Y (born 1980-) = 19% Generation Z (born after 2000). NatGen. British Social Attitudes Survey, 32, 2015, (http://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk) Hansard Society. Audit of Political Engagement 11. The 2014 Report, with a focus on the accountability and conduct of MPs. Hansard Society, 2014: 26, (http://www.hansardsociety.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Audit-of-Political-Engagement11-2014.pdf) “The youngest age groups, particularly 18-24s, are those most likely to say they are not registered or to claim not to know. Only 69% of respondents in this age group say they are registered compared to a national average of 90%. In contrast, respondents aged 45+ all reported registration levels of 96% or above. […]Given that young people (18-34) are those most likely to be in rented accommodation there is a clear association between age, housing tenure and electoral registration levels” (Hansard Society, 2014: 41). “The fact that on average across the Audit series only one in four (25%) 18-24 year olds have said they would be certain to vote underlines the need for continuing concern about the health of electoral participation among young people” (Hansard Society, 2014: 26). “There are few differences by gender, social class and ethnicity on this question. There is, however, evidence of different attitudes by age. Younger respondents are much less likely to claim support for a party than older age groups: just 23% of 18-24s claim to be at least a ‘fairly strong’ supporter of a party compared to 44% of those aged 75+ who say the same. Conversely, just over half of 1824 year olds (53%) declare themselves not to be a supporter of any political party but this is a view shared by only 24% of those aged 75+” (Hansard Society, 2014: 45). 6 Methodology In order to assess the quantitative and qualitative nature of online political communication of political party youth wings, I monitored a majority of their social media output, for the six months before the general election. I observed the official web pages, official Facebook pages and official Twitter tweets of Conservative Future, Young Greens, Labour Students, Young Labour, Liberal Youth and Young Independence.6 This entailed making screenshots of the relevant web pages every week and on specific dates, such one month before the general election and the days party manifestoes were launched. For quantitative analysis, I calculated the frequency (how often there were changes to web pages and tweets), authorship (who made the tweets), and actuality (when changes, posts and tweets were related to a specific news event). For qualitative analysis, I measured the contents (what were the pages, posts and tweets about), tone of message (were the pages, posts and tweets sending a positive or negative message), and the objective (what were the pages, posts and tweets attempting to achieve, e.g. encourage young people to get on the electoral register, to vote, to for a specific party). It was largely straightforward to carry the quantitative analysis as I only had to monitor and add up statistics and thus the results can be considered as mostly objective. However, the qualitative analysis was much more time consuming and required interpretation and thus the results are more subjective. Table 1: Number of web site changes, facebook page change and official tweets, among official political youth wings, Britain, November 2014-May 2015 Political youth wings Number of official website changes Number of official facebook page changes Conservative Future Liberal Youth Labour Students Young Labour Young Greens Young Independence 7 Number of official tweets The Electoral Commission is working in partnership with Facebook so that young users of the social networking site can now add a “Registered to Vote” life event to their timeline, which can be shared with their friends. The Commission launched a nationwide public-awareness campaign on 16 March. Bite the Ballot a not-for-profit group campaigning for schools and colleges to encourage young voter registration. Their Verto smart phone app aims to rebrand politics in an interesting, engaging way and help young people decide who to vote for. Their Democracy Day on 15 April will encourage young people to organise registration rallies and voter-engagement sessions. The National Union of Students (NUS) ran a national competition involving the nation’s 600 student unions to find ideas to get their members to vote. The best will receive up to £10,000 to fund events and projects. Student volunteers will also be knocking on doors and inviting their peers to get themselves on the electoral register. The League of Young Voters a UK-wide campaign to get young people voting, The League of Young Voters is helping people decide who to vote for through a “Vote Match” quiz. It is also training and supporting Young Voter Champions to campaign and mobilise people locally, as well as encouraging young people to share political messages, stories and ideas in creative ways. Rock Enrol! A government learning resource to introduce registering and voting to school classes and youth organisations. The games and materials in the resource aim to inspire young people to discuss and debate what they care about whilst considering why they should register to vote. Youth Counts! Democracy Challenge a programme for young people developed by UK Youth and members of UK Youth Voice, a national steering group of young people from all over the UK. It uses a range of imaginative activities to engage participants in discussions about democracy, registering to vote and their role as active citizens. VInspired is a charity are running a #SwingtheVote campaign in which 10 YouTubers discuss 10 different issues that appeal to young voters over 10 weeks until 20 April. The videos aim to steer clear of party-political jargon and give young people straight answers to their voting queries. Votes@16 a national campaign aimed at changing UK law to allow teenagers to vote at 16. Young people are encouraged to email and lobby their MPs, organise debates and run their own campaigns either locally, through their schools or at university. 8 Bibliography BERRY, Richard and MCDONNELL, Anthony. Highly Educated Young People are Less Likely to Vote than Older People with much Lower Levels of Attainment. Democratic Audit and LSE. 2014, (http://www.democraticaudit.com/?p=2752) BRAND, Russell. Revolution. London: Century, 2014. BRITISH ELECTORAL STUDY (BES). Face to Face Surveys. 2010, (http://www.britishelectionstudy.com) BRUTER, M. & HARRISON, S. 2009. Tomorrow’s leaders?: Understanding the Involvement of Young Party Members in Six European Democracies. Comparative Political Studies, 42. COLLIN, Philippa. Young Citizens and Political Participation in a Digital Society: Addressing the Democratic Disconnect (Studies in Childhood and Youth). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. CONSERVATIVE PARTY. Conservative General Election Manifesto 2015. 2015. CROSS, W. & YOUNG, L. 2008. Factors Influencing the Decision of the Young Politically Engaged To Join a Political Party: An Investigation of the Canadian Case. Party Politics, 14, 345-369. DAHLGREN, Peter. The Political Web: Media, Participation and Alternative Democracy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. DELANEY, Sam. Madmen and Badmen. What Happened When British Politics Met Advertising. London: Faber and Faber, 2015. DENVER, David and HANDS, Gordon. ‘Issues, Principles or Ideology? How Young Voters Decide.’ Electoral Studies, 9(1), 1990, 19-36. DENVER, David. Elections and Voters in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. DENVER, David; CARMAN, Christopher; JOHNS, Robert. Elections and Voters in Britain. Third edition. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. DIGITAL DEMOCRACY COMMISSION. Open Up. London: 20 January 2015, (http://www.parliament.uk/business/commons/the-speaker/speakers-commission-on-digitaldemocracy/ddc-news/digital-democracy-commission-report-publication) EDWARDS, Rick. None of the Above. Your Vote is Your Voice. Don’t Stay Silent. London: Simon & Schuster, 2015. ELECTORAL COMMISSION. Great Britain’s Electoral Registers 2011. London: Electoral Commission, 2011. FIELDHOUSE, Edward; GREEN, Jane; EVANS, Geoff; SCHMITT, Hermann; and VAN DER EIJK, Cees. British Election Study, Internet Panel Wave 2, 2014, (http://www.britishelectionstudy.com/dataobject/2015-british-election-study-internet-panel-wave-2) GOULD, Georgia. Wasted. How Misunderstanding Young Britain Threatens Our Future. London: Little, Brown, 2015. HACKETT, Claire. ‘Young People and Political Participation’, pp. 81-88 in Jeremy ROCHE and Stanley TUCKER (eds.). Youth in Society. London: Sage, 2004. HARRIS, Anita; WYN, Johanna; YOUNES, Salem. ‘Beyond Apathetic or Activist Youth: “Ordinary” Young People and Contemporary Forms of Participation’. Young, 18, London: Sage, 2010, pp. 932. 9 HAY, Colin. Why we Hate Politics. Cambridge : Polity Press, 2007. HEIDAR, Knut. 2006. Party membership and participation. Handbook of Party Politics. London: Sage, 2006, pp. 301-315. HENN, Matt ; WEINSTEIN, Mark. and WRING, Dominic. A Generation Apart? Youth and Political participation in Britain. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 4, 2002, pp. 167192. HENN, Matt; WEINSTEIN, Mark; FORREST, Sarah. ‘Uninterested Youth? Young People's Attitudes towards Party Politics in Britain’, Political Studies, 53(3), 2005, pp. 556-578. Ipsos MORI. How Britain Voted in 2010. 2010, (http://www.ipsosmori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/poll.aspx?oItemId=2613) Ipsos MORI. How Britain Voted in 2015. 2015 (http://www.ipsosmori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/poll.aspx?oItemId=2613) KALLION, Kirsi Pauliina and HAKLI, Jouni. The Beginning of Politics. Youthful Political Agency in Everyday Life. London and New York: Routledge, 2015. KENDALL, Liz. Over 200,000 Young People have Fallen off the Electoral Register: Time to get them back. New Statesman, 5 February 2015, (http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2015/02/over-200000-young-people-have-fallenelectoral-register-time-get-them-back) LABOUR PARTY. Labour General Election Manifesto 2015. Changing Britain Together. 2015, (http://b.3cdn.net/labouruk/89012f856521e93a4d_phm6bflfq.pdf) LAMB, Matthew. Young Conservatives, Young Socialists and the Great Youth Abstention: Youth Participation and Non-Participation in Political Parties. Doctor of Philosophy, University of Birmingham, 2002, (http://etheses.bham.ac.uk/518/1/Lamb03PhD_A1a.pdf) LIBERAL DEMOCRATS. Liberal Democrat General Election Manifesto 2015. Liberal Democrat publications, 2015. LOADER, Brian; VROMEN, Ariadne; XENOS, Michael. The Networked Young Citizen. Social Media, Political Participation and Civic Engagement. London and New York: Routledge, 2014. MARSH, David et al. Young People and Politics in the UK: Apathy or alienation? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. MARTIN, Aaron. Young People and Politics Political Engagement in the Anglo-American Democracies. London and New York: Routledge, 2012. MORTIMORE, Roger, et al. Young People’s Attitude Towards Politics. Nestlé Family Monitor, MORI Social Research Institute, 2003. MUXEL, Anne. Avoir 20 ans en politique. Les enfants du désenchantement. Paris: Seuil, 2010. MYCOCK, Andrew and TONGE, Jon. 2012. The Party Politics of Youth Citizenship and Democratic Engagement. Parliamentary Affairs, 65, pp. 138-161. OFFICE FOR NATIONAL STATISTICS (ONS). Social Trends 41, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. PATTIE, Charles; SEYD, Patrick and WHITELEY, Paul. Citizenship and Civic Engagement: Attitudes and Behaviours in Britain. Political Studies, 51, 2003, pp. 443-468. PICKARD, Sarah. ‘A Conservative Future? Youth and the Conservative Party,’ pp. 75-93, in Agnès ALEXANDRE-COLLIER and Bernard D'HELLENCOURT (eds.). Le Parti conservateur Britannique. Observatoire de la Société Britannique, 4, 2007. PICKARD, Sarah. ‘The Youth Vote and Electoral Communication in the UK and the USA, 20052008,’ pp. 107-127, in Renée DICKASON; David HAIGRON and Karine RIVIÈRE DE FRANCO (eds.). Stratégies et Campagnes Électorales en Grande-Bretagne et aux États-Unis. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2009. 10 PICKARD, Sarah. ‘What’s the Point? The Youth Vote in the 2005 General Election,’ pp. 21-32, in Les Elections législatives de 2005 au Royaume-Uni. Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique, 13(3), Paris: Presses de la Sorbonne Nouvelle (PSN), 2005. PICKARD, Sarah. et al. (eds.). Les Politiques de Jeunesse au Royaume-Uni et en France: Désaffection, répression et accompagnement à la citoyenneté. Paris: Presses de la Sorbonne Nouvelle (PSN), 2012. PICKARD, Sarah. 'Sleaze, Freebies and MPs: The British Parliamentary Expenses and Allowances Scandal', pp. 117-141, in David FEE and Jean-Claude SERGEANT (eds.). Éthique, Politique et Corruption au Royaume-Uni. Aix-en-Provence: Presses Universitaires de Provence, 2013. PICKARD, Sarah. Youth Vote. Young People and Political Participation in Britain. London: 2016 [forthcoming] PIRIE, Madsen and WORCESTER, Robert. The Big Turn-Off. London: Adam Smith Institute, 2000. RUSSELL, A. Political Parties as Vehicles of Political Engagement. Parliamentary Affairs, 58, 2005, pp. 555-569. SANDERS David; CLARKE Harold; STEWART Marianne; WHITELEY Paul. The 2005 General Election in Great Britain. Report for the Electoral Commission. British Election Study (BES), 1979-2005. SCULLION, Richard; GERODIMOS, Roman; JACKSON, Daniel; LILLEKER, Darren (eds.). The Media, Political Participation and Empowerment. London and New York: Routledge, 2013. SLOAM, James. The ‘Outraged Young’: How Young Europeans are Reshaping the Political Landscape. Political Insight, 4, 2013, pp. 4-7. STOKER, Gerry. Why Politics Matters. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. VAN BIEZEN, I., et al. Going, going, . . . gone? The decline of party membership in contemporary Europe. European Journal of Political Research, 51, 2012, 24-56. TRANMER, Jeremy. ‘From Young Socialists to Young Labour: The changing face of left-wing youth politics in Britain,’ pp. 45-58, in Sarah PICKARD, et al. Les politiques de jeunesse au Royaume-Uni et en France: Désaffection, répression et accompagnement à la citoyenneté. Paris: Presses de la Sorbonne Nouvelle (PSN), 2012. Legislation HM Government. Representation of the People Act, 2000. HM Government. Representation of the People (England and Wales) Regulations, 2001, number 341, The Stationery Office (TSO), (http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2001/341/contents/made) 11 Websites Bite the Ballot, (http://bitetheballot.co.uk) Electoral Commission, (http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk) League of Young Voters, (http://www.leagueofyoungvoters.co.uk) National Union of Students (NUS), (http://www.nus.org.uk) Office for National Statistics (ONS), (http://www.ons.gov.uk) Rock!Enrol, (http://www.rockenrol.me) Vinspired, (https://vinspired.com) Votes at 16, (http://www.votesat16.org) Youth Count Democracy Challenge, (https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/youthcount-democracy-challenge) Conservative Future (Conservative Party) http://www.conservativefuture.com https://www.facebook.com/ConservativeFuture https://twitter.com/consfuture Young Greens (Green Party) http://www.younggreens.org.uk https://www.facebook.com/younggreens https://twitter.com/younggreenparty Labour Students (Labour Party) http://www.labourstudents.org.uk https://www.facebook.com/labourstudents https://twitter.com/labourstudents Young Labour (Labour Party) http://www.younglabour.org.uk https://www.facebook.com/YoungLabourUK https://twitter.com/younglabouruk Liberal Youth (Liberal Democrats) http://www.liberalyouth.org https://www.facebook.com/liberalyouth https://twitter.com/liberalyouth Young Independence (UK Independence Party) https://www.facebook.com/YoungIndependence http://www.youngindependence.org.uk https://twitter.com/yiofficial 12 Tables 13 Table 1: Population by sex and age, UK, 2011 All Males Females 65+ (age group) 10,488,000 4,640,000 5,848,000 16-24 (age group) 7,460,000 3,821,000 3,639,000 Source: Office of National Statistics (ONS). Social Trends 40, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan. 2010. Table 2: Results of the 2015 UK general election (seats in House of Common and percentage) political party seats % of votes Conservative Party Labour Party Liberal Democrats Green party Other political parties 307 258 57 36 29 23 28 12 Total 650 100 Table 3: Registered voters (of population), UK, 1979-2015 year 1979 1983 1987 1992 1997 2001 2005 2010 registered population (%) 18-24 year-olds (%) Table 4: Proportion of population registered to vote on electoral roll according to age group, 2015 year number percentage (%) 18-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65 + all 14 Table 5: General election voter turnout (of registered voters), UK, 1979-2015 Year 1979 1983 1987 1992 1997 2001 2005 2010 2015 all age groups (%) 76.0 72.7 75.3 77.7 71.5 59.3 61.3 65.1 18-24 year-olds (%) N/A N/A N/A 68 60 39 37 44 Ipsos MORI, 2010. How Britain Voted in 2010.7 http://www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/poll.aspx?oItemId=2613 Source: MORI, 1992-2015. Table 6: Non-voting, by age group, general elections, UK, 1979-2010 year non-voting all age groups (%) non-voting 18-24 year-olds (%) 1979 1983 1987 1992 1997 2001 2005 2010 14 17 14 13 21 29 29 27 26 23 24 38 46 55 Sources: David SANDERS, Harold CLARKE, Marianne STEWART, Paul WHITELEY. The 2005 General Election in Great Britai. Report for the Electoral Commission and British Election Study (BES), 19792005. 2005. Source: British Election Study (BES), 2010. http://bes2009-10.org 15 Table 7: Voting for each political party according to age group, 1997-2015 Conservative Party age group Labour Party Liberal Democrats other parties 1997 18-24 all 27 31 49 44 16 17 8 8 2001 18-24 all 27 33 41 42 24 19 8 6 2005 18-24 all 28 33 38 36 26 23 8 8 25* 30* 35* 2010 18-24 all 2015 18-24 all Source: British Election Study (BES), Face to Face Surveys, 2010. http://bes2009-10.org Table 8: Voting for each political party according to age group, 2015 age group Conservative Party Labour Party Liberal Democrats other parties 18-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65 + Sources: MORI, Final Aggregate Analysis, (General Election), 7 May 2015. 16 Older and highly education members of the population tend to participate more in elections in advanced democracies. However, there is a large difference between the turnout of young people and old people, in Britain (see Table x based on Ipsos-MORI and British Election Study statistics). This age group gap is wider in Britain than in other advanced democracies (Berry and McDonnell, 2014). This is despite much greater proportion of young people having a high level of educational attainment compared to older generations. We need to remember that low turnout among young people is not just a ‘young people problem’. It is also evidence of wider problems within our political system, which would discourage a person of any age from voting. But there may well be reforms that can be tailored particularly for young people that help support their participation: for instance, better provision of online election information, which may suit people that are highly mobile in geographical terms, and accustomed to using the internet in many aspects of their lives. Britain’s older generations have clearly picked up the voting habit at a time when political, economic, even technological circumstances were very different. In Britain, official turnout figures report the percentage of people whose names are on the official register. […] People are accidentally left off (most commonly young people who would become 18 before the registration lapsed) (Denver et al, 2012: 30). The "likely" figure from December 2010 shows that registration has "not kept pace with a rising population", the Electoral Commission report says. The government is planning a switch from household to individual voter registration aimed at reducing fraud. For Georgia Gould, his is likely ro exacerbate the decrease in voter registration among younger people (Gould, 2015: 49). The watchdog says a change is needed but urged ministers to hold a household canvass in 2014 to keep numbers up. In its report, the commission warns that nearly half of those missing from the register - around 2.6m - believe they are registered to vote. Many people wrongly think you are automatically registered to vote if you are 18 or over, it adds. Voting in elections is just one form of political participation. Charged with symbolism of democracy as it is. Signing petitions, contacting a politician, demonstrating, occupying public and private places. 17 12 juin 2015 More than half (57%) of adults think people should be able to vote regularly online on key political issues and legislation, with the number rising to 72% among 18 to 24 year olds. The YouGov poll revealed only 23% of adults think politicians are effective at using online digital media to engage with the public, despite 88% of respondents agreeing social media has transformed the way people communicate. Richard Jones, founder of EngageSciences, the tech firm which commissioned the poll, warned democracy is under threat if politicians don’t respond quickly to the public’s growing frustration with Westminster. "The results clearly show the current political process is dead. Whilst digital disruption is having a transformative effect on most industries and sectors, UK politics remains stuck in a system developed for the age of the horse, not the internet. "The political process needs to be updated now – not in five years’ time. We need to revolutionise political communications in this country and use digital media to build a system of direct democracy. Only then will we properly address the growing disconnect between politicians and ordinary people." 18 Could political party youth wings galvanise young Brits to vote? As interest in Ukip's Young Independence surges, youth wings of political parties may be the best hope of staving off apathy in the young. by Lucy Fisher Published 1 August, 2014 - 17:33 Interest in Ukip's Young Independence, for party members aged under 30, is surging. Photo: Getty Ukip's Young Independence, the party’s youth wing, launched its annual conference today in Birmingham. The number of under 30s attending is modest at 140, but it is the party's largest youth summit so far. It marks a surge in interest in the party from young voters in the past eight months. Last week Ukip announced that membership of its youth wing in the eastern region has increased 100 per cent since the beginning of this year. 19 The youth wing has experienced an explosion in growth nationally too, with membership up 40 per cent since March this year to 2,600 members at present. Ukip hopes to hit a target of 3,500 young members by next August. While membership is increasing rapidly, Ukip still has some way to go to rival the Conservatives. The Tories claim that Conservative Future, their youth wing for Under 30s, has 15,000 members and is the largest youth political organisation in the UK. Comparisons with the other parties are difficult to draw. Labour refuses to disclose the breakdown of membership of its youth organisations, which include a group for 14 to 20 year olds, and another for 20 to 26 year olds. Meanwhile the official website for Young Labour, which is linked to on the party’s main website, comes up with an error message at present. The Lib Dems do not publish their figures either. The decline in partipation of young citizens in British politics is reaching constitutional crisispoint. The UK now has the worst record in Western Europe for the gap between youth voter turnout and overall turnout. Over recent decades, voter turnout among 18 to 24 year olds have fallen sharply to under 50 per cent in UK general elections. It is predicted that the Coalition’s individual voter registration reforms will damage youth participation at the ballot boxes next May even further. So are political party youth wings a good bet for galvanising young people and encouraging them to take an interest and vote? Tim Stanley, a journalist and historian with personal experience of intense involvement in youth politics, is wary about people getting deeply involved in politics too young. A former chair of the Cambridge University Labour Club, who joined the Labour party at age 15, he regrets his former earnest involvement with politics. Debating the matter with former Conservative minister Ann Widdecombe on the Today programme on BBC Radio 4 this morning, Stanley lamented failing to “sleep around” and enjoy his adolescence and early twenties. He said: “If you’re young, you’re better off spending your time on something more useless.” He added that young people committed to politics “tend to be immature, tend to be driven towards the fringes, they tend to see life as very straightforward and easy and they've got all the answers. You quickly discover you haven't.” He added: “You wake up one day and think: what have I done with the last few years of my life.” Widdecombe rejected his pessimism. “There’s nothing wrong at all with young people thinking on serious matters, even if they’re going to reject what they think in later years, getting involved in local politics and thinking about how the country is run.” 20 She added: “If you don’t get engaged, if you’re not interested when you’re younger, when exactly is that interest going to come?” Jack Duffin, the 22-year-old chairman of Ukip’s Young Independence, staunchly defends the importance of having young voices in politics. He told me today that he is firmly on Widdecombe’s side in this debate. “Youth politics are fantastic,” he said. “I can’t wait 20 years for Labour or Tory governments to destroy my future even more. Our generation will have to live with the mess these governments are making.” cott Redding • 8 months ago The Green Party is at 18% among students. They have a leading Young Green (Amelia Womack) running for the party's deputy leadership in Sept. Why write an article on young voters and UKIP? 12 JoeDM Scott Redding • 8 months ago "The Green Party is at 18% among students." .... and then they grow up, get a job and join the real world. o o 10 • Boy Charioteer JoeDM • 8 months ago Yes, the one inhabited by people like Fred Goodwin and the executives of RBS who despite wasting £46 billion of taxpayer handouts still planned bonuses of £576 million for the executive for their "business acumen". Welcome to the real world. I'll stick with the Greens. Boy Charioteer. (62 and a half). JoeDM • 8 months ago "As interest in Ukip's Young Independence surges..." Very encourging !!!! channel.fog • 8 months ago Indifference isn't apathy. Just as abstention isn't apathy. Though I favour spoling the ballot paper. I joined the Labour party when I was 18. I left when I was 19 when I realised it was no place for socialists. 21 Anon channel.fog • 8 months ago I could not agree more with your opening sentence. Britain's young today have lived through governments comprising all three major parties and they are far from impressed. Labour's foreign wars and disastrous immigration policies, the Tories' strangling opportunities for young people through pernicious economic policies and then its victimisation of the poorest, the Lib Dem's duplicity and betrayal of the young student population and its complicity in the Tories toxic agenda. To quote Paxman 'its a veritable Smorgasbord'. R.B.Stewart • 8 months ago Yes but talking about youth - was a brilliant letter by an 8 year old (teported in the Guardian) sent to govt. critisisng their policy on arms for Israel. I remember at 11 years old booing the Royals as they visited my city as the equally poor adults were fawning, and at school I caused sone consternation at 11 amongst some teachers when I wrote' - 'Why do so few have so much when so many have so little'. I hadn't learnt about question marks!I But I must admit I am still thinking of Cameron and May's recent photo opp - no not Cameron today with the brownies but at the flat of suspected illegal immigrants (innocent until proven guilty). Just think you could be sat in your home and the police burst in and arrest you under suspicion of committing a crime - you are taken away and Cameron and May enter your home (a potential crime scene) to launch a olicy on the issue you have been arrested for. As the National Lottery says - IT COULD BE YOU! R..B.Stewart R.B.Stewart • 8 months ago Cameron and May made A BIG MISTAKE with this and Labour should force them to make a public apology! terence patrick hewett • 8 months ago The young have their priorities right: And a morbid obsession with poitics is not one of them mobhi • 8 months ago Have these state schooled youngsters seen the photo of a smirking NIge resplendent in public-school blazer? And the last UKIP leader! Hasn't he retired to his estate and ghillies(servants, not dancing brogue) in the highlands of Scotland? All quite mystical, you know. Still helps in sorting out the officers and men problem. Corporal H swat • 8 months ago Flipping UKIP Spads in the making. As stomach churning as Wm Hagues first nouting at Cons Conference aged 16. Where is the infant prodigy now! Fed up with politics and off to a retreat to write books and make even more money. Go and get a a proper job young man! mobhi • 8 months ago 22 Somewhere in his 1969 book on dissent and rebellion Norman F Cantor mentions that there's never been a successful 'youth' revolution. It seems older and wiser heads are needed to focus the action. Nigel in his school-blazer does seem somewhat to be in his second childhood. Is he really the man to lead UKIP's massed ranks? And why no mention of Sir Oswald? Yes, he was knocked over by some hooligans in a London political commotion but the Met did try their best! Street Order Josh Chown • 8 months ago There aren't two separate Labour organisations for young people split on age as the article says. There is Young Labour, for 14-26 year olds and there is Labour Students, for students. • Share › o o o http://www.newstatesman.com/politics/2014/08/could-political-party-youth-wingsgalvanise-young-brits-vote o 23 "Young people must see politics as a vehicle for change once again" Young people aren't voting. It’s a problem that has been acknowledged by everyone from Russell Brand to conservative commentators. by New Statesman Published 2 April, 2015 - 14:07 Turnout amongst young people continues to be poor. (Photo: Getty) The Panel Stephen Bush (chair), editor of The Staggers Ollie Middleton, Labour's parliamentary candidate for Bath Darren Hughes, deputy director of The Electoral Reform Society Frances Scott, founder of the 50:50 Campaign 24 Young people aren't voting. It’s a problem that has been acknowledged by everyone from Russell Brand to conservative commentators. Polling conducted by Ipsos Mori after the 2010 election found that less than half (44 per cent) of 18-24 year olds voted (compared to more than 73 per cent of over 55s). What's going on? Many blame disillusion with the political system, one that young people see as littered with hollow promises, infighting and stagnation. Yet while this caricature of the "apathetic" voter may reflect what we see at the polls, that doesn't mean young people don't care about politics. Turn to Twitter or Facebook, for instance, and you'll find debates aplenty, often young-person led. Research from Nottingham Trent University found that nearly two thirds of 18-year olds claim an interest in politics, yet say they are "turned off" by politics and political parties. The role that social media should play in re-engaging young people and getting them to the polls this May was the topic of a recent New Statesman debate, hosted in partnership with Tata Consultancy Services (TCS). The debate marked the launch of ElectUK, a new app from TCS that allow users to track, analyse and visualise Twitter conversations about the upcoming election. The Staggers' editor Stephen Bush, who chaired the debate, began be reminding us that this was the first election for the "digital natives." "Today's government is younger than Twitter and Facebook," he said. "The generation voting for the first time has grown up with the internet in their homes, in their schools. So how can parties engage with them?" Keep it real The question is without a simple answer. But with more than a third of young people saying social media could influence their vote, politicians are giving it their best shot. Well more than half of MPs are now on Twitter (409 out of 650) and the Conservative party is reportedly spending £100,000 a month on Facebook alone. Labour, meanwhile, has invested in a digital campaign driven by Obama's former election strategists. With over four million election-related tweets already analysed by the ElectUK app, it’s clear that social has the potential to play a major role in engaging young voters. But simply showing up to the party isn't enough, warned Darren Hughes, deputy director of the Electoral Reform Society. If politicians treat social media as little more than a mouthpiece for politics-as-usual, they'll lose their listeners. "Simply packaging up the currently way politics is done into 140 characters will fail," he said. "The social media generation is looking for authenticity. If politicians don't demonstrate an interest in a range of specific issues, then they will fall flat." Apathy and access Panelists agreed that young people are more politically engaged than the picture painted by statistics. "I dispute the term apathy," said Ollie Middleton, Labour's candidate for Bath who would, at 19, be the youngest MP ever if elected. "I don't think the majority of young people are apathetic about politics, in the broadest sense of the world." The problem, for Middleton, is the obtuseness of the political system. 25 "It's about making politics accessible," he said. "Young people have become deeply disillusioned with the way in which we do politics, with elements of the system that are broken. The job of politicians is to ensure that young people do see politics as a vehicle for change once again." Hughes said there isn't political disengagement among young people, so much as a shift from the party politics of older generations to issues-driven voting. "Only 13 per cent of young people have a sense of partisanship," he explained. "They are interested in issues, but they don't look for the solutions in a particular party. They will protest and petition, online and offline, to make their point." But what about votes? Yet the question remained, if young people do care about political issues, why aren't they voting? Frances Scott, founder of the 50:50 Campaign which advocates for gender parity in parliament, said that "a lot of activity on social media doesn't necessary translate into action". "Andy Murray's 'Let's do this' tweet was re-tweeted 18,846 times, but the Yes Campaign still didn't win," she said in reference to the Scottish referendum. She said that online petitioning, despite being an "old fashioned" way of laying on political pressure, is still an effective social weapon. "I was inspired by the No More Page 3 campaign and the significant numbers of signatures it generated. Social media can have a lot of power in that way." A question came from the audience - does social media really spur change? Or does it just make it easier just to "click 'like'" but not actually vote? "Social media is a powerful tool," said Middleton, "we've seen government topple during the Arab Spring as a result of it. But if you aren't addressing the underlying problems of disillusionment and disengagement, then social media is only relevant to a point. " Hughes agreed that the hardest task is “motivating people to vote”, and that this will require “changing our politics to make it more real and more relevant”. The evidence shows that social media is a chance for politicians to do just that – to connect with the issues that young people care about. But they must do so with authenticity. For those that can’t, it will be a major opportunity missed. Designed, built and delivered by Tata Consultancy Services, ElectUK turns your smartphone into an advanced social media analytics tool, giving you the ability to identify and share online trends around the upcoming election. The app is free to download and is available on both iOS and Android devices. Just search for ‘ElectUK’ in the Apple Appstore or Google Play Store. Visit www.tcs.com/ElectUK for more information or follow @ElectUK on Twitter for all the latest updates from the app. http://www.newstatesman.com/2015/04/young-people-must-see-politics-vehicle-change-onceagain 26 The Youth Leaders’ Debate 2015 Britain’s First Ever Youth Leaders’ Debates Join us for Britain’s First Ever Youth Leaders’ Debate With civil unrest rising around the globe and the western economies struggling to recover from the 2008 financial crash, politics is rapidly changing. Youth involvement in British politics is on the rise and an outright majority seems a thing of the past. With this backdrop, SHOUT OUT UK and CHANNEL 4 are launching Britain’s First Ever Youth Leaders’ Debate, which will see the youth wings of the seven major British party’s debate on a variety of crucial issues. When: 28th April 2015 Where: In Central London, London, W2 3NA. The Debate The debate will loosely emulate the television debates that occurred in 2010 and the latest 7 way ITV debate. The questions will be a mix of set questions from social media and from the Audience, taken in a similar fashion to the Freespeech debate. The Parties All the youth wings of the seven major British parties have confirmed participation which includes: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Conservative Future – Youth wing of the Conservative Party Liberal Youth – The Youth wing of the Liberal Democrats Party UK Independence – The Youth wing of the UK Independence Party Young Greens – The Youth wing of the Green Party Young Labour – The Youth wing of the Labour Party Plaid Cymru Youth – The Youth wing of the Welsh National Party 27 How to get involved and stay in touch: 1. The Facebook Event Can Be Found HERE For media, Interview requests and Press passes: Please email office@shoutoutuk.org The Speakers Alexandra Paterson National Chairman of Conservative Future Education: Born in Manchester and attended Altrincham Girls Grammar School in Trafford. BA in Media from the University of Liverpool and MA in Journalism from London College of Communication. Studied for the Graduate Diploma in Law at night school at BPP Law School Manchester, whilst working full time. Political Experience: Was originally involved with Conservative Future back in 2007, but took a break for a few years to focus on studies. Became actively involved with Greater Manchester Conservative Future in 2012 and was elected Chairman in 2013. Attended the Young Britons’ Foundation Summer Conference in Washington DC in July 2014 where Alexandra had public speaking training from John Shosky, Ronald Reagan’s speechwriter and TV training from the Leadership Institute. Alex Harding National Chair, Liberal Youth 28 Education: Born and raised in Ipswich, Suffolk. Currently at university in London studying BA Art & Design. Political Experience: LGBT activist; campaigned heavily on legislation for same sex marriage. Alex became the National Communications Officer of Liberal Youth in late December 2013 before running for the National Chair in November 2014. Jack Duffin Young Independence Chairman Education: 29 Went to a state comprehensive in Bedfordshire, studied A-Levels before going to University at Brunel. Did not complete degree. Political Experience Previously a Conservative before joining UKIP in May 2012 when they truly ‘came of age’. Been involved in the youth wing of the party as secretary, London chairman, deputy chairman and now chairman. Stood unsuccessfully in the May 2014 local elections in Hillingdon. Jack is the UKIP candidate for Uxbridge and South Ruislip in the May 2015 General Election. Hannah Ellen Clare Young Greens Senator Education: Born in Harlow, Essex. In 2011, moved to Liverpool to study a BA in English and Politics at the University of Liverpool. Political Experience: Stood for the Young Essex Assembly aged 13 and was re-elected age 15, along with being elected to the UK Youth Parliament. Tackled issues surrounding public transport, political education and university fees. After a period of disenfranchisement from three-party politics, Hannah joined the Green Party in early 2013. Has debated for the University of Liverpool over 20 times at national and international competitions. Glenn Page National Chairman (2014-2015) of Plaid Cymru Youth 30 Education: Born in Penarth, Vale of Glamorgan; raised and schooled in Carmarthen in the west of Wales, moved to Cardiff in 2009 to Study BA Ancient History at Cardiff University before graduating in 2013. Political Experience: Former National Chairman of Plaid Cyrmu Youth 2014-15 recently re-elected to serve as Policy Officer. A passionate grassroots activist, Glenn campaigns against cuts, austerity & war and in favour of social-justice, free education& the rebalancing of wealth and power across these islands. Finn McGoldrick Chair of Labour Students 31 Finn McGoldrick is the National Chair of Labour Students. The official student wing of the Labour Party, Labour Students is the largest party political student group in Britain with clubs on campuses up and down the country. Previously she was a representative in NUS, working as the LGBT Officer after attending the University of Manchester. http://www.shoutoutuk.org/youth-leaders-debate-2015/ 32 Conservative Future: What we contribute to student politics Feb 04, 2011 by CanvasEditor in Issue 4: Student Politics Conservative Future is the largest political youth organisation in the UK with over 15,000 members, though you could fail to be convinced about this at universities such as Sheffield, where we appear a tiny minority of students. As the University of Sheffield branch, Conservative Future has a number of roles, including supporting Conservative candidates in all elections, both local and national, and representing the younger side of the Conservative Party. We leaflet, we canvas and we offer a forum for political debate to all interested parties in our local area. Aside from our political activities, this academic year Conservative Future has taken part in a Union volunteering project, with plans to volunteer again, and we will also be holding a charity fund-raising event. In Sheffield, one of our most important roles is creating a balance to the political opinion offered to our fellow students. Right now it is crucial that Conservative Future are on hand for students, to offer debate on, and the reasons behind, the Coalition’s policies, even in the face of the often overwhelming anti-Tory bias on campus. As long as there are Conservative-minded students, there will be a Conservative Future to involve young people in politics and address the issues that matter to them. There is a certain Tory stereotype that students can have, thanks in part perhaps to Harry Enfield’s Tory Boy sketch, of all white male middle-class snobs and politicos. This image is hugely extorted by left-wing student groups, but amongst our other roles, CF tries to break down this comic image. Our activities are not purely political, but also involve a number of different socials to allow our members to bond, and we are certainly not all of the slapstick Henry Enfield mould; it wasn’t a chauvinistic political party that gave the UK its first female Member of Parliament, its first Muslim female Cabinet minister and its first female Prime Minister. Conservative Future has a number of diverse roles; students come to CF to meet politically likeminded people, but through our events and activities, they end up contributing so much more to the student body and to the local community. Article by Laura Knightly, President of Conservative Future Sheffield, 2010-11. Edited by Vicky Shreeve. http://canvas.union.shef.ac.uk/wordpress/?p=362 Labour Students: What we contribute to student politics Feb 04, 2011 by CanvasEditor in Issue 4: Student Politics “There is no ticket of admission, to public action. Anybody can get through that gate, and anybody can ask that basic question that gets the ball rolling.” – Ralph Nader 33 Students have a voice, and deserve to use it. It should be nurtured, encouraged, and promoted wherever possible. Never should a person be intimidated to state their opinion or express themselves in a manner they don’t see fit, neither should a person fear that their opinion is worthless, or that it will be ignored. Sheffield Labour Students exists to help people find their political voice, to persuade people that they are important; and that their opinion matters. It is easy to be cynical and to believe that student politics offers nothing because it cannot change anything. This is false; students can offer change. We have a voice; a voice that can join together with other voices in our society. Far too often, our numbers have been viewed by our elders as unopinionated, lazy and overly materialistic. This is a disservice to all young people, who will form the next generation of citizens. We are optimistic, we look forward; we aspire to better lives and a peaceful society in which all can prosper. How do we document this case? If the protests over education cuts and rises in tuition fees proved one thing, it is that students do care about the future of the society they will soon inherit. In these formative years when the opportunity is greatest, it is they who can reach out beyond the confines of the university campus and become the active citizens that keep our communities vibrant and make a more harmonious society. We in Labour Students choose to support the Labour Party because we believe that it is best placed, in spirit and motive, to improve the rights and the standard of living of all people. Student politics is more than just joining a political party. It is a social consciousness. We take this principled position; let us not stand idly by while injustices are inflicted on our society, but provide an alternative to the welfare and despair that some believe is the only choice. It is not hard to make a difference, even though the first steps can seem intimidating. It begins by asking the question; getting involved; meeting like minded people; but most importantly having fun, kicking up a fuss, trampling on toes, and getting your point across! Article by Chris Olewicz and Hue Wales. Edited by Vicky Shreeve. http://canvas.union.shef.ac.uk/wordpress/?p=344 Liberal Youth: What we contribute to politics Feb 04, 2011 by CanvasEditor in Issue 4: Student Politics Traditionally Liberal Democrats have rarely influenced student politics, at least with regards to forums such as the National Union of Students. Instead those institutions have been filled with labour careerists, middle class Trotskyites and eco-fascists. One need only look back to the presidency of Phil Wollas to recognize that the NUS has long been a training ground for future giants of the labour party. Outside of the incestuous world of sabbatical officers however, it is true that the liberal democrats have made an impact on the politics of students, if not students’ politics as such. Liberal Democrats were at the forefront of campaigns against the war in Iraq and the introduction of top up and tuition fees under labour governments. I remember with fondness forge press circa March 2010 when articles on such matters regularly turned into slanging matches between liberal democrat and labour students fighting for every vote in the then marginal Sheffield central. Our brush with government has revolutionized this however, whereas once Liberal Democrats were forever standing on the concourse handing out leaflets promising such things as free university tuition for all, government has forced us to change tack. 34 Had a Conservative government increased tuition fees rather than a coalition, one could easily picture Nick Clegg standing sanctimoniously in front of the students union attacking both main parties with aplomb. The role of the Liberal Democrats in student politics is now much diminished. Everyone from Aaron Porter to Clare Solomon now regularly attack Clegg’s mendacity and Simon Hughes’s obfuscation, and do little to challenge them. As the labour party has slunk back into opposition once again, the natural order has been restored. Although ‘Red’ Ed Milliband refused to address the rioters in Whitehall after promising to, we can see that the two are made for each other. Liberalism it seems will generally have nothing more than a two-bit part in student politics, which is perhaps for the best. Article by Duncan Ayles, member of Liberal Youth. Edited by Vicky Shreeve. http://canvas.union.shef.ac.uk/wordpress/?p=350 Student Politics in History: The Legacy of the 1960s Feb 04, 2011 by CanvasEditor in Issue 4: Student Politics My views are a product of youthful idealism. Delving into the histories of my age group has stripped me of any sense of originality. Aged 16 with an attention span that could only cover three minutes of heavy guitars and promiscuous lyrics, I fully engaged in a 50 minute lesson on the American Student Movement of the 1960s. Youth is impulse and passion, and the images, slogans and risk takings of that generation’s students corroborate. France, a country synonymous with social upheaval and Britain, a country marked by drastic transformation in culture and society followed the Americans by laying their ideology bare, free for the international stage to witness in shock and awe. This article briefly chronicles the 1960s student movements in the USA, France and Britain and how this revolutionary zeitgeist can be an inspiration for students today however remote the decade is to us. It tends to be the case that protests happen for the right reasons. We can question the rise of communism in Eastern Europe but accept that the pre-revolution Russian oligarchy rendered the common man helpless without being labelled a radical. This is the same for the American student protests; call them intellectual idealists or the middle class youth with the time and money to complain, but what they were standing for was far bigger than their studies or their socio-economic backgrounds. On their brand new television sets they saw the unjust occurrences in Vietnam. Their white picket fence communities neighboured the slums of the black urban poor. In their homes they saw their mothers rendered to a life of involuntary servitude and subservience. They wanted to make a change. Though the American student movement story is the most recited, it is important to realise the student movement as a network of international organisations. May 1968 saw the French student movement charge; they protested against the Vietnam War and the overbearingly traditional system in their universities. They also fought for the workers who so often were treated as mere cogs in the 35 capitalist system. Posted on the walls of Nanterre University were slogans such as ‘Take Your Dreams for Reality’ showing that this was a group of people ready to move into new times. They wanted to make a change. A similar movement resided in the UK with the Vietnam War and racism filling much of the rhetoric. Unlike America, many of these idealists found themselves with Black and Asian neighbours only 20 years prior to the 1960s. They idolised ‘R and B’ and Blues musicians from the Deep South and the reggae artists from the West Indian tropics. They integrated with this culture to a point where a sense of colour could only be discussed in a complimentary tone but witnessed others using race as a way to exclude those who didn’t belong in land we call the United Kingdom. They wanted to make a change. It cannot be doubted that these student movements were just a section in a wider protest, but their support acted as a catalyst for change validating the age old saying of ‘strength in numbers’. The number of people who partook in protest activity can also be overemphasised. For every Kent State protester their was a student bound by tradition, for every French radical, there was a student who wanted peace, for every hippie, there was a student who attended The Rivers of Blood Speech in the spring of ’68. But while this is true, it is important realise that such conflict is commonplace when tradition is challenged. It is how protestors react to opposition which is the important factor. They were born in a time of racial segregation, separation without equality. But a path had been laid giving them the opportunity to shout for what they believed as they reached the cusp of adulthood. It is easy to forget as a black female in the 21st Century of the hardships that my predecessors faced. It would be treason to indulge in this life as if it could never have been worse, forgetting that the hand we have been dealt is better than it would have been less than a century ago, because of these revolutionaries. How do the issues of another decade relate to the issues of today? They relate because once again students are making headlines because they are shouting against jeopardising the futures of future students. The 60s protesters have aged, yet reminisce on the actions they took to help create a better world and students today hope to be doing the same in their later life. Language is used in the same vein as the protestors of the 60s: speeches of struggle and fight, outbursts of anger, vilification from the media (whether unjust or not) being labelled as idealists out of touch with brute reality. Yet in retrospect, the entire protest movement of the 60s is fastened under a utilitarian belt: they stood for what has become popular opinion. In short, the movement has been legitimised because they stood for what we see now as right. This is because the movement is now a propaganda device urging the people who have to power to make constitutional change to see our perspective. If our movement maintains strength and cohesiveness we can be as successful as the sixties protesters in France, America and Britain. Unlike them, we’ve had a taste of what we are fighting for. To have it taken away would be a discredit to the lesson we have been taught from history: that we have the power to make a change. Article by Michelle Kambasha. Edited by Liz Saul. http://canvas.union.shef.ac.uk/wordpress/?p=379 36 37 Research Committee Sessions (RC10) Electronic Democracy Panel: RC10 — Digital Campaigning and Political Organizations Paper: Paper not available Party Politics or Social Politics? The Relationship between Political Participation through Social Media and through Parties in Comparative Perspective Abstract: Social media such as Facebook and Twitter offer political parties important opportunities to reach voters, as well as allowing citizens to discuss political issues, get political information, and encounter opportunities to participate in electoral and non-electoral politics. Many of social media’s political implications, however, stem more from the demand side, that is, users’ attitudes and behaviors towards politics, parties, and politicians, than from the supply side, that is, parties’ adoption of these tools. This paper focuses on the demand side of politics on social media and, in particular, on users of a specific social networking site that has become very popular among both politicians and citizens: Twitter. Through a unique set of surveys of representative samples of Twitter users who posted at least one politically-related tweet during the 2013 elections in Australia, Italy and Germany, we investigate how Twitter users who post about politics relate to political parties in terms of both attitudes and behaviors. As regards attitudes, we assess respondents’ levels of trust in parties. With respect to behaviors, we measure the extent to which respondents engage with party-related activities, both online (e.g contacting them through email or social media) and offline (e.g. being members, making a donation, and volunteering). Multivariate analyses allow us to evaluate whether political engagement on social media predicts trust in political parties and engagement with party-based online and offline activities. Finally, the comparative design of our research allows us not only to describe the differences and similarities between Australia, Germany and Italy, but also to assess the implications of their different systemic features such as compulsory voting, strength of party organizations, and political culture. Authors: Cristian Vaccari Royal Holloway - University of London / Università di Bologna, United Kingdom Lauren Zentz University of Houston, United States 38 heme: Research Committee Sessions (RC22) Political Communication Panel: RC22 — The Impact of Digital Technology for Political Engagement and Participation Paper: Paper not available Social Media and Youth Voting at the Municipal Level in Calgary Abstract: Low turnout at elections among Canadian youth is a problem. In spite of the relative ease of voting, the number of young people who do remains very low. Their relative absence likely results in a disconnect between their interests and the mandates awarded to governments. Moreover, voting is a habit that, when adopted early on, tends to “stick” into adulthood. The flipside to this is that ignoring the polling booth is also habit forming. Despite efforts, there has been little in the way of progress in reversing this trend. One stream of research that offers a promising avenue of inquiry looks to social media use and its importance for the political participation and attitudes of youth. The paper will further our understanding of this relationship by examining the connection between two common online networks, Facebook and Twitter, and political participation during a civic election. Using original data collected from an online survey of students from the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada, we examine the nature of this link during the 2013 Calgary municipal elections, which have had a historically low record of overall turnout. In 2010, however, the turnout level jumped by twenty points to a high of 53.4 percent. Many have identified one candidate, Naheed Nenshi, as responsible for the jump due to his targeted use of social media in his campaign. This paper will examine how election campaigns that explicitly adopt social media as a voter turnout tool impact youth turnout. Authors: Brenda O'Neill University of Calgary, Canada Ashley Valberg University of Calgary, Canada 1 2 3 4 5 According to official statistics, there were 7.5 million 18-24 year-olds in the UK mid-2013, which represented about 12% of the total UK population of 64.1 million (ONS). There were approxiamtely 1.5 million 16 and 17 year-olds. In Britain, registration is obligatory according to Section 23 of the Representation of the People (England and Wales) Regulations 2001, and those who do not are liable to a fine. Britain is slowly moving to individual registration. https://www.gov.uk/electoral-register/overview “You must register to vote if you’re asked to do so and you meet the conditions for registering, eg you’re 16 or over and you’re British or a national of an EU or Commonwealth country. […] When you can register in more than one place: It’s sometimes possible to register at 2 addresses (though you can only vote once in any election). For example, if you’re a student with different home and term-time addresses, you may be able to register at both. Use the register to vote service to make 2 separate applications. Your local Electoral Registration Office will look at each application and tell you whether you’re allowed to register.” The voting age was lowered from 21 to 18 in 1970, which “added some 3 million young people to the register” (Denver et al, 2012: 31). “By 2020, secure online voting should be an option for all voters. The Speaker’s Commission wishes to encourage increased efforts in voter education and recommends a fresh, bold, look at the national curriculum in this regard. (Recommendation 21) 39 6 7 The Commission strongly encourages the political education bodies and charities to consider how to make available and publicise trustworthy information about candidates and their policies, including by means of voter advice applications. (Recommendation 22) The Digital Democracy Commission also notes a clear indication from a range of comments received that the profile and knowledge of the Electoral Commission needs to be improved, as it is a vital source of information to voters, with a website that is an Aladdin’s cave for those wishing to participate in the UK’s political process. (Recommendation 23) The DDC recommends that the Electoral Commission should consider how best to establish a digital election ‘results bank’. (Recommendation 24) The Commission fully endorses the draft Political and Constitutional Reform Committee recommendation that “the Government and the Electoral Commission should examine the changes which can be made to provide more and better information to voters, and should actively support the work of outside organisations working to similar goals.” (Recommendation 25).” I did not monitor closely YouTube posts. MORI General Election, Final Voting Aggregate Analysis, for 1992, 1997, 2001, 2005. www.mori.com/polls/2005/election-aggregate.shtml, May 2005. No precise data is available on how many young people actually vote because general elections are secret ballots. Statistics have been obtained for recent general elections through aggregated opinion polls, exit polls and specific studies. Whilst no precise data is available on how many young people actually voted because general elections are secret ballots, statistics have been obtained for the last four general elections through aggregated opinion polls and specific studies. For 1992-2005 see: MORI. 2005. General Election, Final Voting Aggregate Analysis, www.mori.com/polls/2005/election-aggregate.shtml. For 2010 see: Ipsos MORI, 2010. How Britain Voted in 2010 (based on more than 10,000 interviews). 40